Black Lives Matter should promote Pan-African solidarity and denounce U.S. imperialism in Africa

The Black Lives Matter movement has had a major impact in raising awareness about police brutality and the ongoing persecution of Black people in the United States but has been remarkably parochial in evading discussion of U.S. imperialism in Africa and around the world.

While protest signs commemorating George Floyd and calling for defunding of the police have been legion at many of its demonstrations, few if any signs have called for the abolition of AFRICOM or indictment of Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama for presiding over the overthrow and lynching of Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi.

The latter omissions stem in large part from the ignorance of most of the U.S. population—whether Black or white—about Africa and the consequences of U.S. imperialism there.

The major fault for this ignorance lies with U.S. educational institutions and the mass media, which have for decades promoted stereotypes about the continent and its people, and evaded discussion of how it has been adversely impacted by Western colonialism.

Africans are still frequently characterized as “tribal people”—with all the attendant negative perceptions that spring from this word—whose poverty, conflict and disease-ridden countries can only be salvaged under foreign oversight.

Leaders who stand up to the Western powers like Qaddafi are demonized while those who acquiesce to their agenda are presented more favorably.

African voices are meanwhile marginalized—especially those that adopt a Pan-Africanist and anti-imperialist message—and many Blacks come to internalize the message that they are inferior.

Manufacturing Hate

Milton Allimadi, a professor of African history at John Jay College and founder of Black Star News, has just published the book, Manufacturing Hate: How Africa Was Demonized in Western Media (Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing, 2021), which provides a history of racist stereotyping and media bias toward Africa that has helped skew American public opinion.

Allimadi starts his story with a discussion of European travelogues in the 18th and 19th centuries.

These presented Africans as being “trapped at a level of intellectual, socioeconomic and political development that Europeans had transcended centuries earlier” and helped justify the alleged obligation of Europeans to conquer and colonize Africa.

Sir Samuel Baker—Governor-General of the Equatorial Nile Basin (today South Sudan and Northern Uganda) between 1869 and 1873—set the standard in his 1866 book, The Albert N’Yanza Great Basin of the Nile, in which he wrote that “human nature viewed in its crude state as pictured among African savages is quite on a level with that of the brute, and not to be compared with the noble character of the dog.”

Joseph Conrad’s classic novel Heart of Darkness (1902) similarly depicted Africans as “primitive savages” and warned Europeans of Africa’s propensity to drive normal people insane.

[Source: narrativepress.com]

[Source: lucysnyder.com]

The views cultivated by Conrad and other writers helped fuel support for colonization—which was considered a noble yet hazardous undertaking.

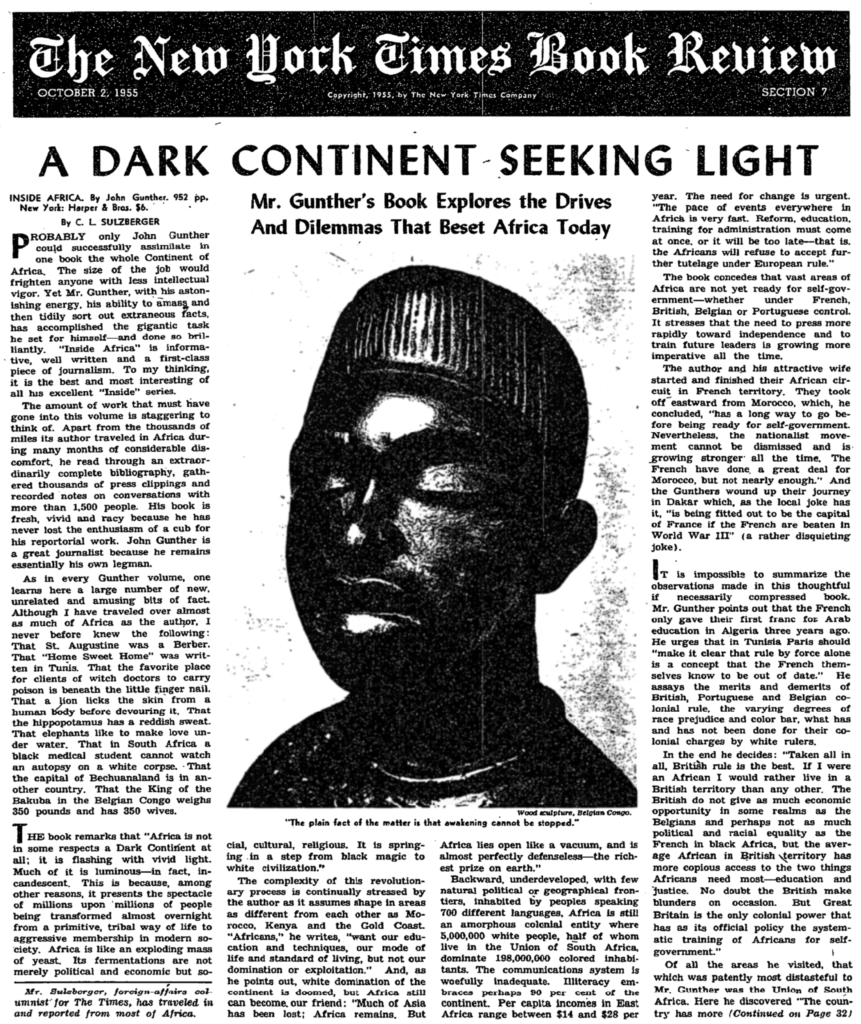

The New York Times’ Heritage of White Supremacy

The New York Times, in one of its earliest accounts of Africa published on July 1, 1877, claimed that Africans were “arrested at a position not so much between heaven and earth, as between earth and hell.” The article continued:

“The “poor dark savages” on the “dark continent” had “scarcely advanced beyond the element of art and science and even language” while, “from within, [they] devoured and destroyed one another, willingly offering their throats to the knives of sorcerers, or paving the deep grave of some bloody monarch with the living trembling bodies of his hundreds of young wives.”

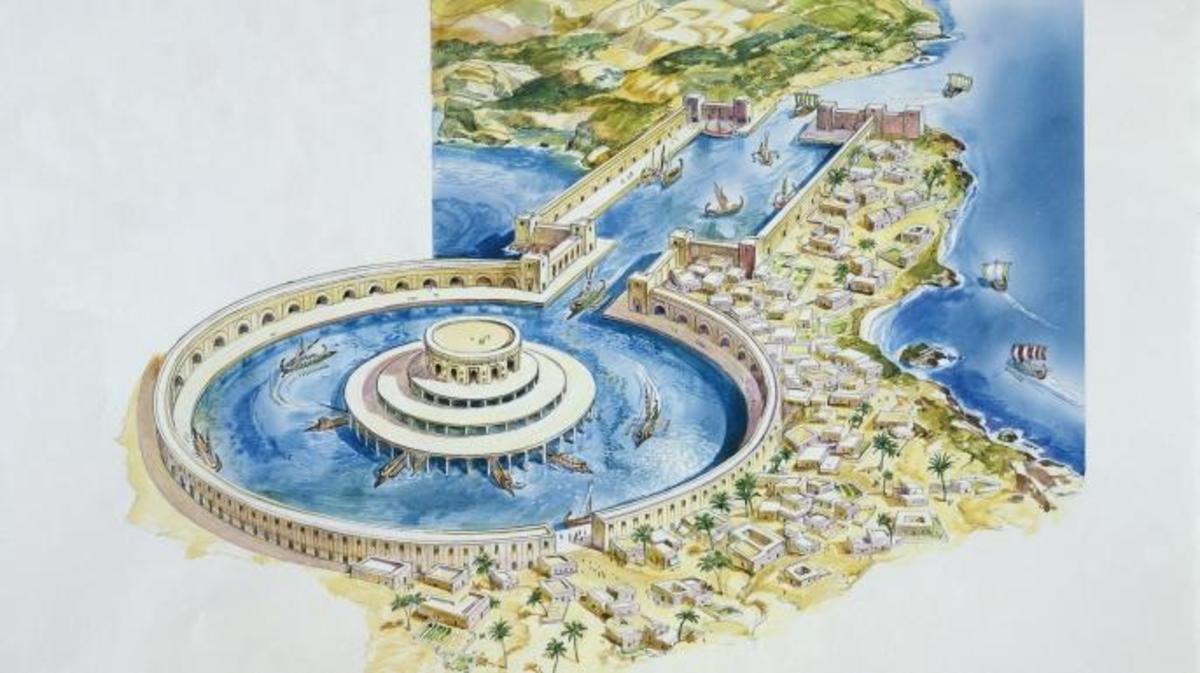

These prejudicial comments ignore the flourishing of great African civilizations like ancient Carthage and the Songhai and Mali empires before the era of the slave trade and European colonization, which weakened and divided the continent.

The Times strongly endorsed British colonization over Germany’s and Russia’s, claiming that “the introduction of European civilization would be most justifiable, and might well repay the cost.”

The Times went on to depict the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War in South Africa as a “contest between a civilized nation with great military and naval power and inexhaustible resources and a primitive and barbaric tribe [the Zulu], however brave and unyielding … Sooner or later the powerful nation was destined to bring the savage tribe into abject submission or demolish it utterly.”

When Italy invaded Eritrea in the 1890s, the Times published a triumphalist account, claiming that the natives “welcomed the Italians as liberators.”

The Times adopted a more somber tone in reporting on Italy’s humiliating defeat at the Battle of Adwa in 1896—one of the greatest African victories against European imperialism—which the Times characterized as “terrible.”

In the 1930s, when Italy’s fascist leader Benito Mussolini reinvaded Ethiopia trying to reinvigorate the Roman Empire, the Times tried to diminish the significance of the Ethiopian victory at Adwa, while playing up the brutality of the “savage black warriors” who had “slaughtered nearly 40,000 Italians.”

Times reporter Herbert L. Matthews’s dispatch read like a press release from the Italian military command.

Known for his sympathetic reports of Fidel Castro’s rebel band in Cuba during the 1950s, Matthews had traveled in the same car as Italian military commander Marshal Pietro Badoglio as he entered Addis Ababa—and never bothered to interview any Ethiopians.

Herbert L. Matthews [Source: Spartacus-educational.com].

Marshal Pietro Badoglio [Source: italianmonarchist.blogspot.com]

Support for Apartheid

The Times continued its pattern of white supremacy by supporting the odious apartheid system in South Africa from its beginning—and for many years thereafter.

In 1926, the “newspaper of record” published an article by Wyona Dashwood which supported the plan of South African Prime Minister James Barry Munnik Hertzog to segregate and disenfranchise Blacks in the Cape province as a way to deal with “the native factor.”

Dashwood claimed that the new system would help stop tribal fighting and give the “semi-civilized native”—whom she depicted as lazy and prone to theft—the chance to “develop along his own lines” and to begin to adapt some of the more “advanced economic, social and political systems of the white man’s civilization.”

Thirty years after Dashwood’s article, in May 1957, the Times ran a piece by Richard P. Hunt which reported on the perspective of apartheid leaders who had just passed a law empowering the new minister of native affairs, Hendrik Verwoerd, to ban Blacks from churches, clubs, hospitals, schools and other places if they would “cause a nuisance.”

An apartheid regime official was quoted as stating that the new powers were “needed to insure that the relations between black and white were to be those of guardian and ward,” which the article did not dispute.

When reporter Joseph Lelyveld began writing more critically about apartheid in the 1960s, his articles were toned down or distorted by editors, who made the system appear less brutal.

Lelyveld wrote to his editor in January 1983 that “virtually all the original reporting” he had conducted over a one-month period for a piece on the underfunding of Black schools had been omitted; the printed article, he said, was “like a salami sandwich without the salami, just slabs of stale bread.”

Always on the Wrong Side of History

Much like with its support for apartheid, The New York Times and other mainstream U.S. media outlets were on the wrong side of history when it came to African decolonization.

When Times reporter Leonard Ingalls wrote a letter demanding more sympathetic coverage, the foreign news editor, Emanuel Freedman, shot him down, preferring the traditional narrative in which Africans were depicted as “savages” and buffoons.

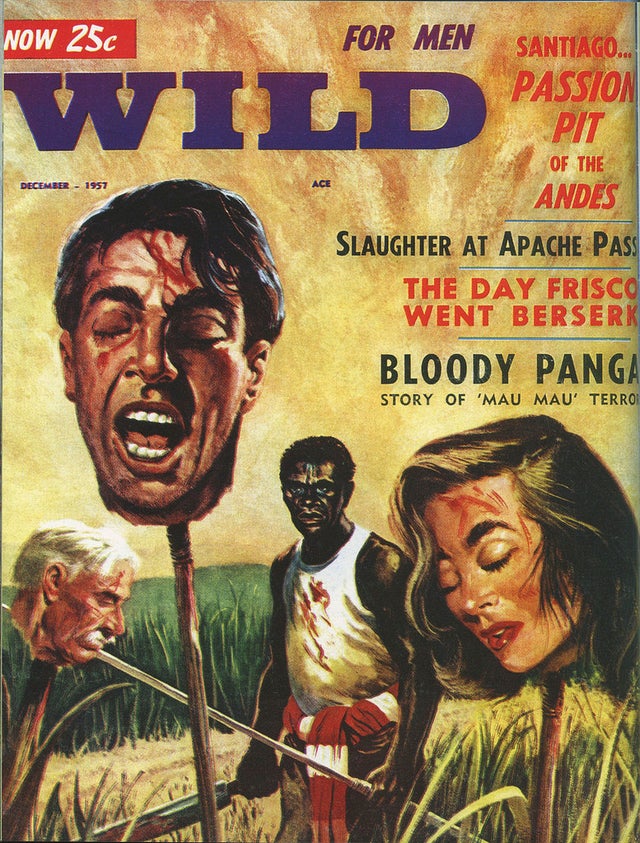

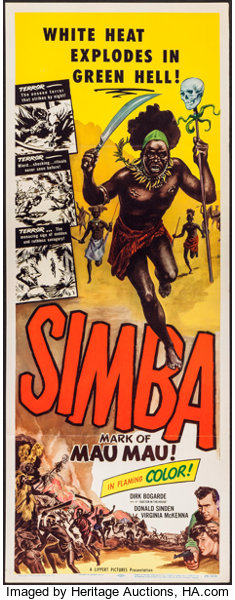

The Times’s coverage of the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya adopted a “witch-craft versus civilization narrative.” The Mau Mau were presented as a “secret tribal society whose campaign of murder [has] forced the imposition of martial law.”

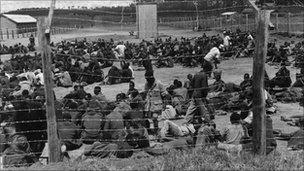

No indication was given that the Mau Mau emerged in response to colonial injustice. Nor that the violence of the Mau Mau rebels paled in comparison to that resulting from Great Britain’s scorched-earth military campaign which led to the deaths of thousands of Kenyans and the detention of thousands more in concentration camps.

Henry Wallace in Burnt Cork

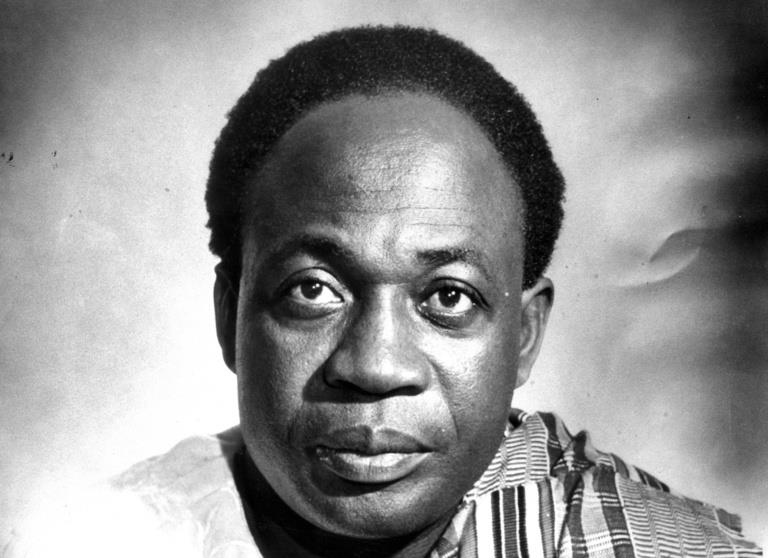

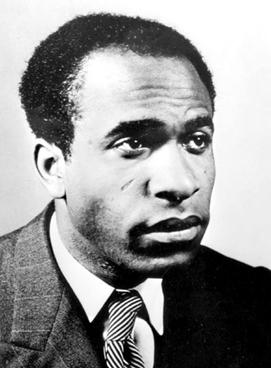

The Times’s Kenya coverage fit with the pattern of demonization of radical anti-colonial movements, particularly when they were led by left-leaning Pan-Africanists like Dr. Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana—who was voted Africa’s Man of the Millennium at the dawn of the 21st century.

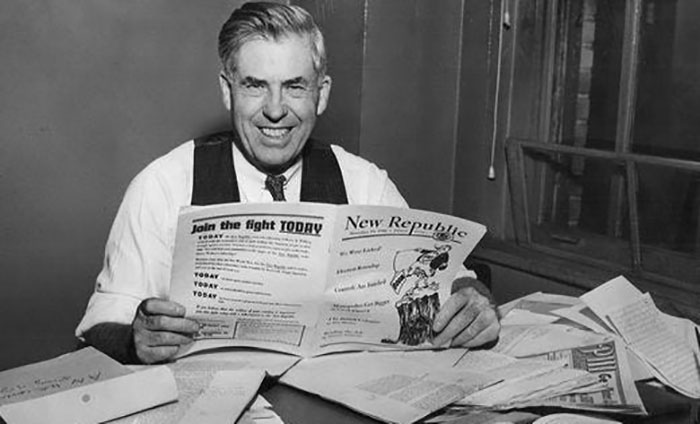

New York Times reporter Homer Bigart—a Pulitzer prize winning war correspondent who was expelled from South Vietnam for criticizing U.S. client Ngô Đình Diệm—wrote to Emmanuel Freedman in 1960 that “Dr. Nkrumah is Henry Wallace in burnt cork. I vastly prefer the primitive bush people. After all, cannibalism may be the logical antidote to this population explosion everyone talks about.”

Bigart’s negative association of Nkrumah with Henry Wallace was reflective of a prejudice not only toward Africans but also toward the left-wing and pacifist views which Wallace had embraced.

Kwame Nkrumah [Source: whatsonafrica.org]

Henry Wallace [Source: versobooks.com]

The comments about primitive bush people meanwhile reinforced deep-seated stereotypes about Africans. And the joke about cannibalism being an antidote to population explosion—a concern reflective of the Western elite’s view of Africans as a threat to be contained—was certainly in poor taste.

Congo

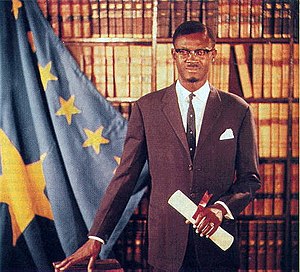

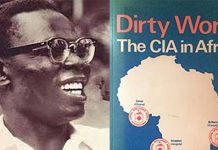

Like Nkrumah, Congolese Pan-African leader Patrice Lumumba was portrayed as a “wild eyed radical.”

Lumumba’s killer, Moïse Tshombe—who led a secessionist drive in the Katanga province backed by Belgian mining interests and white South African mercenaries—was praised in Time magazine by contrast as the “antithesis of the African savage.”

Most admirably, according to Time, Tshombe had “no complexes about being black” and recognized the “brutal side of the African personality, and the phony side of African socialism.”

Patrice Lumumba [Source: wikipedia.org]

Moïse Tshombe [Source: historica.fandom.com]

Pro-Lumumbaist rebels who fought against Tshombe after Lumumba’s assassination were meanwhile depicted by Time as “a rabble of dazed, ignorant savages, used and abused by semi-sophisticated leaders.”

U.S. bombing operations—carried out by right-wing Cuban mercenaries—were hence justifiable, as was U.S. backing of the dictator Joseph Mobutu who was portrayed like Tshombe as a “responsible antidote” to Lumumba-style socialism.

Colonialism Dies Hard

At the end of the Cold War, numerous Western writers took stock of developments in Africa and concluded that the continent should be recolonized.

A characteristic piece from the era by Paul Johnson in The New York Times Magazine was titled “Colonialism’s Back and Not a Moment Too Soon.”

The article was about the U.S. intervention in Somalia, which Johnson considered “a model for action in other African countries facing similar political collapse.” He concluded in a refrain familiar to Rudyard Kipling that “the civilized world has a mission to go out to these desperate places and govern.”

An ever more apocalyptic and racist article was “The Coming Anarchy” by Robert Kaplan, whose Malthusian doomsday scenario read like a description of Africa from one of the 19th century explorers’ journals.

According to Kaplan, conditions in Africa were so dire, absent the white man’s rule, that Africans no longer resembled human beings.

Wherever Kaplan traveled in a taxi, young men with “restless scanning eyes” surrounded him. He described the men as being “like loose molecules in a very unstable social fluid that was clearly on the verge of igniting.”

Rwanda 1994

Historically, Western writers depicted Africans with alleged European features favorably, while demonizing those with so-called negroid features.

During the Rwanda conflict, Tutsis were adopted by some Western writers as honorary “Europeans” while Hutus were presented as the archetypical Africans.

The Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF)—who happened to be staunch American allies—became the “good guys” by extension, and Rwanda’s national army, comprising mostly of Hutu allied with France, became the bad guys.

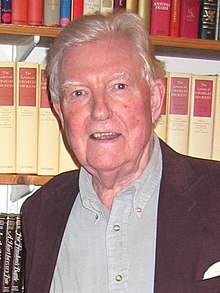

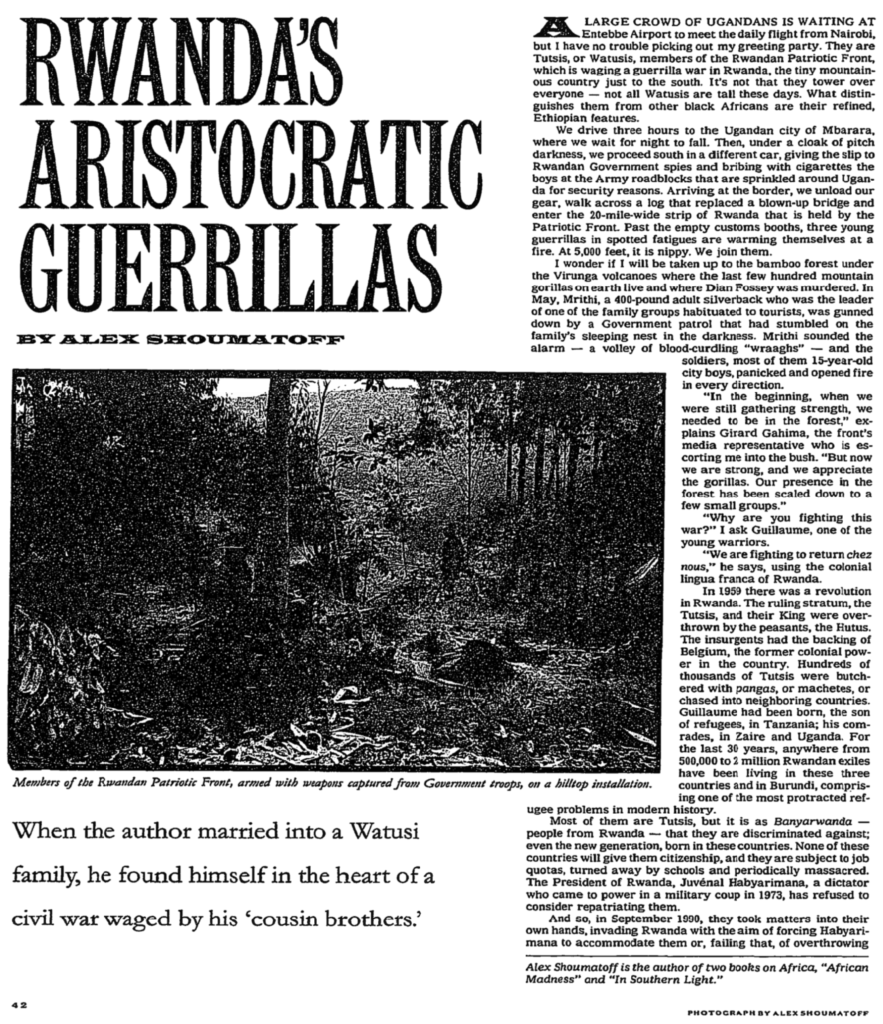

One of the earliest articles to use this racist characterization—which helped cultivate support for the RPF—was Alex Shoumatoff’s “Rwanda’s Aristocratic Guerrillas.” It appeared in The New York Times Magazine on December 13, 1992—two years after the RPF had illegally invaded Rwanda from Uganda and committed legions of atrocities against civilians.

A Marine intelligence veteran who lived for a period on a hippie commune in New Hampshire, Shoumatoff was at the time married to a Tutsi woman, who had been a Ugandan refugee and was the cousin of an RPF spokesman.[1]

His article informed readers that the Tutsis were “refined and had European features,” while the Hutus were “stocky and broad nosed.” He continued that, in the 19th century, “early ethnologists had been fascinated by these languidly haughty pastoral aristocrats [Tutsis] whose high foreheads, acquiline noses and thin lips seemed more Caucasian than Negroid, and they classed them as false negroes…. The Tutsis were thought to be highly civilized people, the race of fallen Europeans, whose existence in Central Africa had been rumored for centuries.”

After the RPF seized power, Shoumatoff wrote another piece for The New Yorker, sizing up the ethnic mix between Tutsis and Hutus in Burundi. Shoumatoff described the Tutsi as “tall, slender, with high foreheads, prominent cheekbones, and narrow features,” a different physical type from the Hutus, who were “short and stocky, with flat noses and thick lips.”

Such racist observations reinforced traditional stereotypes about Africans and painted a stark dichotomy that lent validation to the Tutsis genocidal campaign against the Hutu, which extended into the Congo.

![Forbes Africa on Twitter: "[NEW EDITION] @PaulKagame, Rwandan president & Chair of the AU, graces the December/January issue of our #ForbesAfrica magazine. In an exclusive interview he speaks to our editor @METHILRENUKA](https://covertactionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/forbes-africa-on-twitter-andquotnew-edition-pau.jpeg)

Black Inferiority Complex

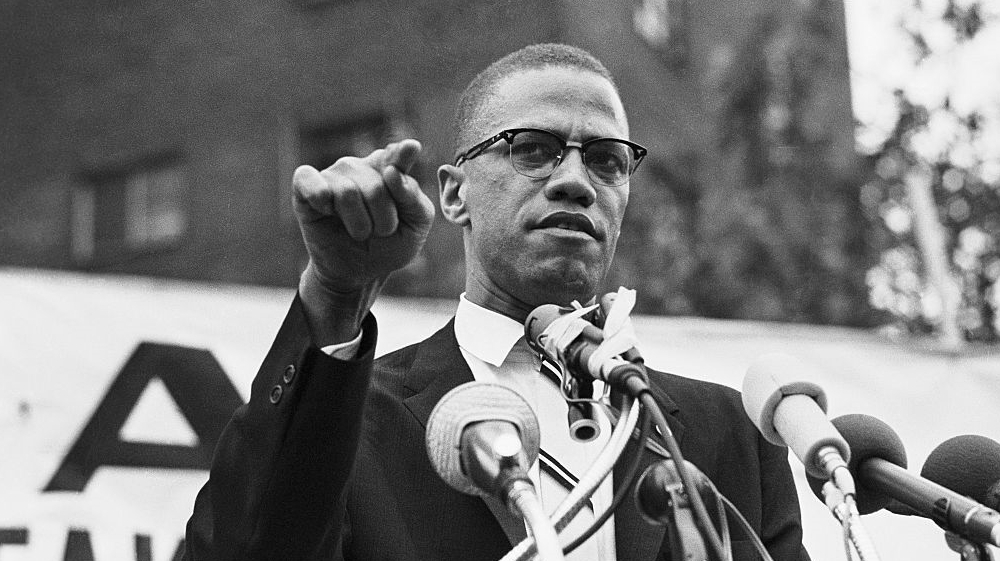

In a February 1965 speech in Detroit, Michigan, Malcolm X spoke about the damaging psychological impact of the demonization of Africa on Blacks. He said that

“the colonial powers of Europe, having complete control over Africa, they projected the image of Africa negatively. They projected Africa always in a negative light, savages, cannibals, nothing civilized. Why then naturally was it so negative it was negative to you and me, and you and I began to hate it. We didn’t want anybody to tell us anything about Africa, much less calling us ‘Africans.’ In hating Africa and hating the Africans, we ended up hating ourselves, without even realizing it. Because you can’t hate the roots of a tree and not hate the tree. You can’t hate your origin and not end up hating yourself.”

Thirty years after Malcolm X spoke those words, The Washington Post published a reactionary article by an African-American reporter, Keith Richburg, “A Black Man in Africa.”

Richburg, who had covered the inter-ethnic massacres in Rwanda, described his revulsion at witnessing the “discolored, bloated bodies floating down a river in Rwanda towards Tanzania.”

Richburg wrote that, as he witnessed the bodies, he realized how fortunate he had been; that he too “might have been one of the victims of the Rwanda massacre or he might have met some similarly anonymous fate in any one of the countless ongoing civil wars or tribal clashes on this brutal continent. And so I thank God my ancestor made the voyage [on the slave ship].”

Richburg’s article formed the basis of his 1997 book, Out of America: A Black Man Confronts Africa, which Milton Allimadi calls “Conrad’s Heart of Darkness for the new century.”

According to Allimadi, Richburg offered a classic case of a Black man caught in the psychic pain of what Frantz Fanon called “internal inferiorization.” Under this condition, negative stereotyping results in self-hatred and a desire to be affiliated with the dominant race.

As a youth, Richburg had been taught to believe that he was superior to other Blacks who came from poorer neighborhoods, talked loudly, had darker skin and nappier hair. When he went to the movies with his brother, they would cheer on the British soldiers attacking “Zulu tribesmen” in film.

This exemplifies the disorder Fanon and Malcolm X described. Its impact ultimately has been to neuter and destroy Black radical movements and solidarity. The legacy can be seen today, among other ways, with Black Lives Matter’s silence about Africa—which should be corrected.

-

An RPF fighter was the best man at his wedding. Previously Shoumatoff had written an article in Vanity Fair about the murder of Dr. Dian Fossey that helped shape the script for the hit movie Gorillas in the Mist. Shoumatoff had served in a U.S. Marine intelligence unit that trained him to be parachuted behind the Iron Curtain and had Russian language training. It is certainly possible he sustained his intelligence ties and that his writing on Rwanda was sanctioned by the CIA. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.

[…] Fuente: CovertAction Magazine […]

[…] Source: CovertAction Magazine […]

[…] Fuente: CovertAction Magazine […]

[…] Font: CovertAction Magazine […]

We are very fortunate to have so many black people in America. Only 13 percent of Black voters voted for Donald Trump. So if it were not for the Black people Donald Trump would still be President.

Here is the latest story of western imperialism in Africa, mostly ignored by the western media:

The United States openly seeks to dominate the world. This becomes difficult as China’s economic power grows while the United States stagnates. The Chinese developed trade relationships with many nations in Africa, a region the United States considers part of its empire. The United States created an Africa Command after the Cold war ended and now maintains dozens of small bases and thousands of troops on the continent. The president of Guinea, Alpha Conde, developed close relations with China and profitable trade deals. China is Guinea’s chief customer for its principal export — bauxite, which used to produce aluminum. China imports half of Guinea’s production that provides half of the world’s aluminum. China provided funds to improve Guinean hospitals and infrastructure to ensure good relations. This friendship upset the United States, so President Conde was ousted in a 2021 coup.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O6O2T_-4Wls

[…] Kuzmarov: Racist Stereotypes About Africa in the U.S. Media Have Long Driven its Rape and Plunder.. … […]

Ed Herman’s “Enduring Lies” shows just how awful Kagame is. The West’s reports on the massacres was the opposite.

That is quite a piece of writing on the history leading to the present but more so speaking

to the future, of important aspects of African development vis-a-vis interests from abroad.

I skimmed but will go back and peruse. Whether blacks in the US have valuable experience

or ideals to offer continental Africans — I dunno — one might also consider whether those

native African blacks have something foundational to offer American blacks? I watched a

You Tube piece that explored the latter theme, featuring American blacks who did return

to live in Africa and quite happily per their account. They were amazed that the black African

population seemed devoid of the filter [apperceptive mass, psychology calls it] of race

consciousness that blacks in America could not shake off, rather seemed to embrace.

This extant obsession, if you will, of seeing oneself and everything else in the world through

the apperception of Race, has a history and according to one Spanish Philosopher of the

early 20th century, an origin from two minds: one the Frenchman Gobineau who explored

the idea that the Aryan race was superior to other races. This idea then introduced the

concept of race to consideration thereafter, or so I think. The other influence followed by

continuing Gobineau’s iconic concept, then introducing first the concept of racism, the

moral culpability of which he laid at the feet of British Protestantism, which he wrote

believed that they and not the Jewish people were the ‘chosen people’ referred to in the

Old Testament. Following that revelation, the pseudo historian [in Ortega y Gasset’s view

[I neglected to mention his name above] Arnold Toynbee invented the concomitant idea

of anti-racism, and he Toynbee being the most ardent champion of, while inculpating

nearly the universe of man including peer intellectuals of the 20th century of being racists.

Ortega y Gasset eviscerates in a manner of speaking [in a metaphor implying Toynbee’s

relation to anti-racism having a sexual component] these newfound idealisms of race

[Gobineau’s] and racism and anti-racism by Toynbee, in Ortega’s rebuttal to Toynbee’s

history of the West and by extension the world — Toynbee’s multi-multi- volume tome,

in Ortega’s ‘An Interpretation of Universal History.’ I think Americans and beyond, but

especially American blacks, will never get beyond the acquired apperceptive mass of

Race, unless they read Ortega’s interpretation of its origins in the book just cited. Jacques

Barzun, former provost of Columbia University, now deceased at 104, thought that

Ortega y Gasset was a most important philosopher, whose ideas would need to be

listened to, particularly by the West which Barzun wrote was already deep in the throes

of decadence in his 1995 ‘From Dawn to Decadence: 500 years of Western Cultural

History.’ Ironically, black Africans — perhaps because they are the majority in Africa —

did not acquire this filter of seeing themselves and the world of man through the filter

of race. Though it is something Westerners might project upon them. They do not the

first thing waking up in the morning, look into a mirror and think: I’m black, a race.

Or so I think.

the OUTcry?

oh…don”t worry…it found a place to live with all the OTHER ”outcrys” related to that country”s policies since, at LEAST WWII…