Far beyond any notion of solidarity between brotherly nations divided by an ocean, the reception of Brazilian exiles in Portugal during the 1970s was marked not by warmth, but by strict surveillance, diplomatic intrigue, and covert maneuvers.

From the perspective of Brazilian intelligence services, Portugal appeared to waver between the moral duty of sheltering the persecuted and the pragmatic—and not seldom cowardly—temptation to yield to pressure from the great powers; a country reborn from the ashes of its authoritarian past, yet still faltering in its first steps toward the freedom it had only recently claimed.

Lisbon, 1976—Spring had arrived with the steady sound of rain. The gentle warmth and the flowering broom promised to imbue the month of March with vibrant, glistening colors, laden with hope and affection. If Portugal’s future seemed bright—with only a few weeks remaining until the approval of the new Constitution and the first free elections in nearly half a century—all was not well in the post-revolutionary paradise.

Across the Atlantic, in the damp and shadowy offices of Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, an unnamed official was meticulously recording every move of those whom the regime had cast out and discarded like refuse. While the anonymous writer seethed inwardly at the very whisper of the word “communist,” the men and women about whom he wrote were mourning the slow death of a nation consumed by hatred. Among them were former army captains, disgraced poets, and journalists who had traded the newsroom for life in hiding. Yet in Portugal, they all bore the same surname: political exile.

To the Brazilian military dictatorship, they were subversives. In Lisbon, however, they were little more than ghosts with an accent, ghosts who, each morning—just after the rooster’s crow — would hurry to the post office to send letters that would never reach their destination, who bought bread with the last coins donated by the Red Cross, and whispered among themselves, in hushed tones, wondering if a place called homeland still existed. However much the Mediterranean climate may have soothed the soul, nothing could ease the burden of having left their country in the hands of butchers, whose last vestiges of conscience—if ever they had existed—would be buried in the dustiest corner of their hearts, locked away beyond reach.

“Lá faz primavera, pá”

As valuable as their testimony would have been to this piece, it is with regret that I must write that the vast majority of the Brazilian exiles of the 1970s and 1980s are no longer on Portuguese soil. I suspect, indeed, that many are no longer among us at all—no longer of this world. In their absence, I turned to the archives. And what I found was the other side of the coin: the perspective of the executioners—men incapable of recognizing in their own actions the contours of an ancient, primal, irrational cruelty. What would their mothers have thought, had they read what I read?

But what kind of world was this, after all, where a simple association became synonymous with conspiracy, where poetry was mistaken for propaganda, and where the mere desire to return to the land of one’s birth was interpreted as part of a “terrorist plot”? After leafing through the 53 pages that make up the document, I was left with the distinct impression that the repressive Brazilian apparatus resembled, in every way, a lazy writer: No matter how hard it tried, it was simply incapable of granting its characters more than one dimension, stripping them of all the features that made them human.

It is true that some of these exiles were, in fact, involved in sabotage campaigns.

Yet this did not mean that all of them shared the same level of involvement, nor that they should be regarded as an existential threat merely for aspiring to a better life than the one they had left behind. A particularly revealing detail lies in the way the documents refer to the Brazilian regime. Unlike other dictatorships—which tend to shield themselves from the term—this one showed no hesitation in calling things by their name, repeatedly referring to itself, quite unabashedly, as a dictatorship with a capital “D.”

In this bleak and sorrowful chapter of Brazil’s history, the university lecturer was inevitably labeled a “communist threat”; the literature student, a “feminist agent”; and the elderly trade unionist, who could barely afford the rent or put food on the table, the “ringleader of an international conspiracy.”

Convinced that the Brazilian exiles in Portugal posed a tangible threat to the integrity and stability of the national order, the Brazilian authorities did not hesitate to deploy considerable financial resources to ensure the regular presence of their spies at opposition meetings. They cared little for the actual purpose behind such gatherings; what truly mattered was that every word be meticulously recorded, transcribed, and promptly forwarded to Brasília, where the State’s bureaucratic machinery would scrutinize it with painstaking attention.

It so happened, however, that the vast majority of the information compiled by these emissaries added little or nothing to what was already widely known—merely reproducing the political opinions of the various participants, men and women recently arrived from Algiers, Paris or Santiago de Chile. Looming over the aggrieved was the ever-watchful shadow of the Brazilian state and its embassy—an entity to which, for reasons beyond my understanding, the Portuguese state seemed to extend a form of safe conduct, a complicit silence.

One hand washes the other

Although I had already come across similar episodes—in which my country chose to yield to the interests of others at the expense of its own commitment to freedom—I must confess that, as a citizen and a journalist, I had never witnessed such a flagrant violation of the rights and guarantees for which the Portuguese people had fought so hard. This very same freedom, it must be said, was ultimately denied to their Brazilian brothers and sisters, who embarked on a long journey to Lisbon in the hope of finding safe harbor.

“On February 24, 1976, the exile and former admiral Cândido da Costa Aragão was dismissed from his post at the Portuguese Navy Library, by express order of the General Staff of that naval force”— reads a Center for Foreign Information (CIEX, in the Portuguese acronym) report dated March 30 of the same year, almost exactly a month later. At first glance, nothing in this excerpt seems to betray any form of external interference or clear indication of Portuguese acquiescence. A less attentive reader might not even raise an eyebrow.

However, while it is true that these words, on their own, would scarcely be enough to make us throw up our hands in alarm, those that follow might just do so:

The news was conveyed to the exile in question by commanders Martins Guerreiro and (pnd) Serrano. These Portuguese officers also disclosed that the decision stemmed from pressure exerted by the Brazilian Embassy and its naval attaché, Commander Valbert Medeiros de Figueiredo. They assured Aragão that he would not be left unsupported. He expressed his gratitude for the protection offered by the aforementioned officers and merely requested a plane ticket from Lisbon to Buenos Aires, where he intended to settle and engage in social work with refugees Avelino Bione Capitani and Alberto Conrado.

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs; CIEX, March 30, 1976.

The report could hardly be more revealing: The Brazilian diplomatic mission, in collusion with its intelligence services, exerted pressure on the Portuguese Navy with the explicit aim of removing an employee who, by mere coincidence, was also one of the leaders of the Portuguese Committee for a General Amnesty in Brazil (CPAGB) and, consequently, an active member of the opposition to the Brazilian military regime in Portugal.

Two months before the aforementioned incident, another former Brazilian serviceman had alluded to similar behavior, confiding to two compatriots—themselves exiles—that his dismissal from the Portuguese Ministry of Social Communication had been “prompted by pressure from the Brazilian Embassy on the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs.”

At no point is the specific reason for his removal disclosed; he simply stated that the information had been relayed to him “by a friendly source within the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) who, naturally, had no inkling that their words would later form the basis of a confidential report.

An Enemy at the Gates

Fate—or whatever agency presides over the world’s contingencies—decreed that the epicentre of Brazilian exiles’ political activity should be located just a few meters from the former headquarters of Portugal’s political police. In the space of only two years, Rua António Maria Cardoso underwent a profound transformation, ceasing to be a symbol of terror and anguish and becoming instead fertile ground for revolutionary ideas.

The irony can scarcely have escaped the attention of Brazilian diplomats and spies. The fact that young revolutionaries had established their base precisely where, for 41 years, a handful of fanatics devised means of subjugating the spirit of Portuguese resistance was an involuntary—or perhaps not so involuntary—provocation, and an undeniably brutal one, to the logic of dictatorships: that fear may cross oceans, but so too can the will to resist.

I strongly urge all those preparing to denounce my subjectivity—which I equate, without shame, to honesty and common sense—to read the 53 pages that comprise the document on which this article is based.

With the exception of the mouldering mass that afflicts the most conservative sectors of Brazilian and Portuguese society—with the exception of those who still fantasize, one hand clutching the Bible and the other their fly, about a past in which the elites arrogated to themselves the privilege of banishing any living soul bold enough to challenge them—the peasant, the laborer, the revolutionary will grasp that, for the oppressive Brazilian regime, any human being endowed with Reason was immediately deemed an instrument of “repudiation of the Brazilian dictatorship.”

It is hardly surprising, then, that the vampires of repression deeply lamented the growing rapprochement between the Brazilian diaspora and the Portuguese progressive movement—a connection which, from the perspective of CIEX and Brazil’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, heightened the risk of losing control over the narrative on the international stage.

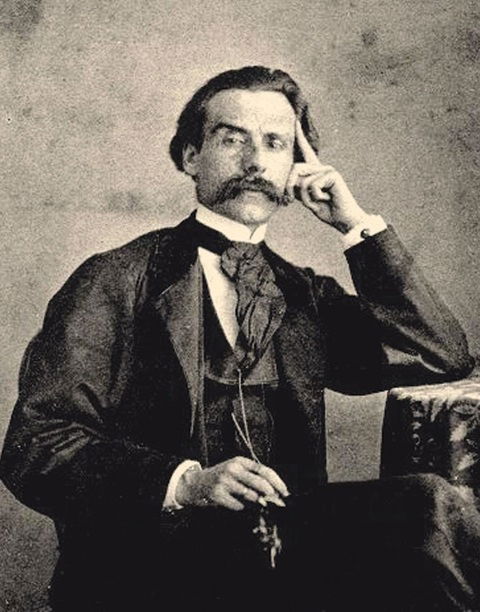

Coined by the Portuguese writer Camilo Castelo Branco—himself the target of persecution for confronting the puritanical morals of a country shackled by its own backwardness—the expression “quem sai aos seus não degenera” (like father, like son) encapsulates, with mordant lucidity, the stance adopted by all, or nearly all, 20th century dictatorships.

Rather than encouraging the free exchange of ideas, they chose instead the perfidious exchange of torture methods—a sinister body of knowledge shared in the shadows of cruel repression—all in the name of a “truth” their subjects longed to see confirmed, but which others, driven by loftier convictions, dared to contradict.

After Cuba had fallen into communist hands, the United States of America—or, more precisely, the imperial itch of Lyndon B. Johnson—fell into a state of alarm, fearing that Brazil might follow the same path. True to its interventionist instinct, Washington rushed to poke its nose where, as usual, it had not been invited. The rest is history.

But when the time came to do the same in Portugal—where groups of progressive youths were striving to reap the fruits of a country under construction—their Brazilian counterparts, keenly aware of the dangers, issued warnings about the harmful consequences of American intervention. To no avail…

Despite the Portuguese state’s passivity in curbing United States interference, there were those prepared to stand up and challenge the imperialist narrative. These individuals, however, were, unsurprisingly, under close surveillance. I refer, in particular, to the presence of the Cuban intelligence service, commonly referred to as G-2, whose reputation also remains, to this day, shrouded in secrecy and controversy.

The individual in question, José Briabri, resided in the same building that housed the Cuban Embassy in Lisbon — at No. 127, Rua Pascoal de Melo, 7th floor, left-hand side—and was allegedly connected to the diplomat Angel Remond, third secretary of that diplomatic mission and, by all indications, the G-2’s “case officer” in Portuguese territory.

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs; CIEX, March 26, 1976.

Who would have thought that opening our arms to freedom and justice could come at such a high cost to Portuguese national sovereignty? Who would have imagined that the country which succeeded in toppling Europe’s longest-standing dictatorship would allow the nation’s enemies to move freely, without reprisal? Who would have predicted that the revolution would culminate in a stage for a war entirely foreign to Portuguese interests? Who would have believed that all this would unfold on the eve of democracy?

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Rafael Baptista is a 24-year-old journalist from Portugal driven by an unwavering passion for storytelling.

Curious and determined, he has spent over four years specialising in Politics and Security, investigating the rise of the far right and clandestine foreign espionage in Portugal. Inspired by Ryszard Kapuściński, Martha Gellhorn and many others, he is constantly on the move in search of extraordinary stories that transcend time.

Rafael can be reached at rafael.baptista2000@gmail.com.