“Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.” — Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1852

For much of the past year, France has been gripped by widespread protests against President Emmanuel Macron’s unpopular pension reform law raising the retirement age from 62 to 64 years.

Despite a national survey showing overwhelming public opposition to the measure, it was enacted by the National Assembly and signed by the second-term president in April, with the controversial invocation of Article 49.3 of the Constitution enabling the benefit cuts to be forced through undemocratically.

As the Macron regime’s rule by decree and police brutality only seemed to fuel the insurrection, the unrest further escalated during the summer after a teenage boy of Algerian descent was killed by gendarmes in a Paris suburb. Although the protests have dissipated in recent months, when France has not been plagued by turmoil at home, its influence abroad has waned after a wave of coups within its former colonies in Africa.

Macron’s policies have fallen equally out of favor internally and the ongoing civil disorder has made France appear more of a failed state than any of its former overseas territories.

The draconian neo-liberal initiatives and the autocratic mechanisms used to impose them reignited mass demonstrations which have become commonplace throughout the former Rothschild banker’s entire tenure in office, starting in 2018 with the “gilets jaunes” (yellow vests) protests against an equally despised fuel tax increase that only came to a halt because of the nationwide coronavirus lockdowns in 2020.

But while they were initially motivated by a surge in gas and diesel prices, Macron’s whole incumbency has been defined by his efforts to gut the social welfare system and an end to austerity was a central demand of the gilets jaunes as well. In fact, the recent pension reform strikes can largely be understood as having picked up where the yellow vests left off.

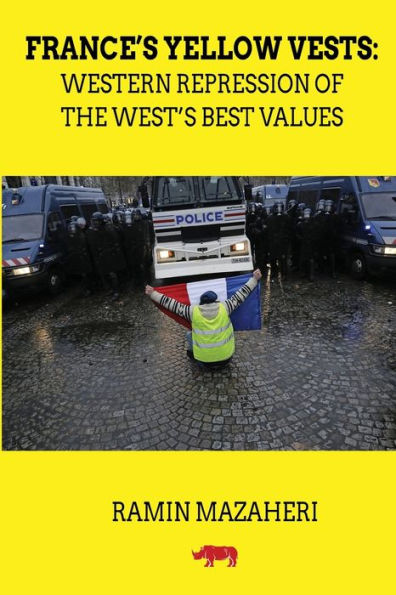

During the popular protests nicknamed after the high-visibility clothing worn by participants in Macron’s first term, journalist Ramin Mazaheri was the correspondent for the Iranian news channel Press TV reporting on the ground in Paris. While much of the mainstream media at the time slandered the populist movement as right-wing tools of “Russian interference,” alternative outlets like the Islamic Republic’s state-owned network provided more even-handed coverage, albeit to a minimal media market in the West.

Now based in the United States, Mazaheri has since published a fascinating book, France’s Yellow Vests: Western Repression of the West’s Best Values, which not only details his first-hand account of the uprising but dispels many of the myths surrounding the politics of the marchers which were actually closer to the left-wing supporters of Jean-Luc Mélenchon. He then places the impact of the movement in a wider context of the country’s revolutionary tradition and progressive political history going all the way back to the overthrow of the Ancien Régime in 1789.

Spanning the last two and a half centuries, Mazaheri chronicles France’s unique place at the forefront of social change, starting with the French Revolution as the advent of political modernity and liberal democracy. Although he acknowledges the pivotal roles played by the 1688 “Glorious Revolution” in England and the American Revolution in 1776 in the transition from feudalism to capitalism, the Iranian correspondent draws an important distinction in his comparison of 1789 with the bourgeois revolutions in Britain and the United States.

While the British Isles may have established the rule of parliament and passed the Bill of Rights, in reality the absolute authority of hereditary monarchy was simply expanded to include the rest of the landed aristocracy. Similarly, in the American War of Independence, power was merely shifted from the British Empire to a new domestic elite in the 13 colonies, as explained in Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States.

According to Mazaheri, it was the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen which truly laid the foundation for modern ideals of human civil rights and the French Revolution which conducted the first truly revolutionary experiment to transform the existing social order, with varying degrees of success in the ensuing decades.

France’s Yellow Vests goes on to highlight France’s distinctive role as a consistent spearhead of radical politics when it notably led the only successful European revolution of 1848 where its king was once again overthrown and the republic re-established, while the other wave of uprisings throughout the continent were put down and monarchy would remain the prevalent form of government until the end of World War I. Still, despite multiple major revolutions in less than a century, it was the bourgeoisie of France which had primarily benefited from them.

As Mazaheri points out, it was not until the short-lived but seminal Paris Commune of 1871 which founded the world’s first socialist democracy, when the working class fleetingly held state power and briefly transcended the empty promises of liberal democracy.

Despite lasting a mere few months, the French revolutionary government nevertheless was a precursor and opening to a period of history which would culminate in the Russian and Chinese Revolutions in the 20th century. Or as Lenin wrote, “in the present movement we all stand on the shoulders of the Commune.”

In his examinations of those aforementioned epochal rebellions, Mazaheri is largely in line with most Marxist historians. Instead, the real strength of the book lies in its provocative but brilliant re-evaluation of the Napoleonic era that completely upends both conventional historiography as well as the orthodox Marxist account of the First Consul of France.

The prototypical view of Napoleon, coincidentally the subject of a forthcoming Hollywood film, has always been that the renegade military general emerged during the Reign of Terror and political chaos following the overthrow of the monarchy, betraying the revolution by declaring himself emperor and marching across the continent as a military aggressor.

Since then, the Marxist theory of Bonapartism itself has generally come to refer to periods of crisis within capitalism when the ruling class uses counter-revolutionary forces to retake power and enact moderate reforms in order to stabilize the economy and prevent further upheaval. For example, even though Napoleon—whom Marx described as a “grotesque mediocrity to play a hero’s part”—introduced meritocracy and dismantled parts of the feudal system, he also reaffirmed old institutions like the Catholic Church as France’s state religion which had previously been disestablished by the Jacobins, among other reversals.

In The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Karl Marx famously observed that history had repeated itself—“the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce”—in reference to the respective coup d’états by Napoleon and his nephew, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, half a century apart.

While Marx opined that Napoleon III and his uncle had each corrupted the popular revolts which preceded their ascents to power, Mazaheri challenges us to rethink that notion and our entire understanding of Bonapartism. As our mutual colleague Jeff J. Brown also observed, Mazaheri’s alternative recounting is often reminiscent of political scientist Michael Parenti’s equally daring The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People’s History of Ancient Rome, which argued that the Roman statesman was really murdered by the ruling elite for introducing land reforms and redistributing wealth to the poor.

Both writers make the case that each head of state has been unfairly maligned as a tyrant because history is written by the victors, or as Napoleon is said to have remarked after his defeat by the British at the Battle of Waterloo, “what is history but a fable agreed upon?”

Mazaheri cites the fact that both Napoleon and his successor are said to have received popular support and were elected in what were, if legitimate, unprecedented plebiscites for the time in Europe. He also critiques what he considers the unnecessary division by historians between the Napoleonic Wars from the French Revolutionary Wars, arguing that all of the post-1789 military conflicts which pitted France against the coalitions of European monarchies were a collective effort to prevent the social achievements of the revolution from growing throughout the continent.

Although he concedes much of the radicalism of the revolution was rolled back by Napoleon (as well as the Thermidorian Reaction which preceded his reign), Mazaheri contends that bourgeois revolutions should be looked at as progressive on the whole if they move the mode of production out of feudal relations toward capitalism and an eventual step forward to socialist democracy. (While that may be true, he neglects to address Napoleon’s re-establishment of slavery in 1802 which had previously been abolished in all the former French colonies, including Saint-Domingue where the colonial government was defeated in the Haitian Revolution.)

Even if one is not fully convinced of his inverse portrayal of Napoleon’s attempt to spread the revolution across Europe as rather a “European War against the French Revolution,” it is undeniably thought-provoking and turns much of the story we are told about such a significant figure on its head. (Then again, historical revisionists have made similar defenses of Hitler and Nazi Germany, who like Napoleon, would make the fateful error of trying to invade Russia.)

Nonetheless, such a controversial revising of the Napoleonic era is a significant departure from the classical Marxist approach. Lenin, for one, would have patently disagreed with his characterization, writing in 1916:

“A national war can be transformed into an imperialist war, and vice versa. For example, the wars of the Great French Revolution started as national wars and were such. They were revolutionary wars because they were waged in defense of the Great Revolution against a coalition of counter-revolutionary monarchies. But after Napoleon had created the French Empire by subjugating a number of large, virile, long established national states of Europe, the French national wars became imperialist wars, which in their turn engendered wars for national liberation against Napoleon’s imperialism.”

Lenin’s view was consistent with Friedrich Engels in his correspondence with Karl Kautsky on the subject of nationalism and internationalism in 1882:

“One thing alone is certain: The victorious proletariat can force no blessings of any kind upon any foreign nation without undermining its own victory by so doing.”

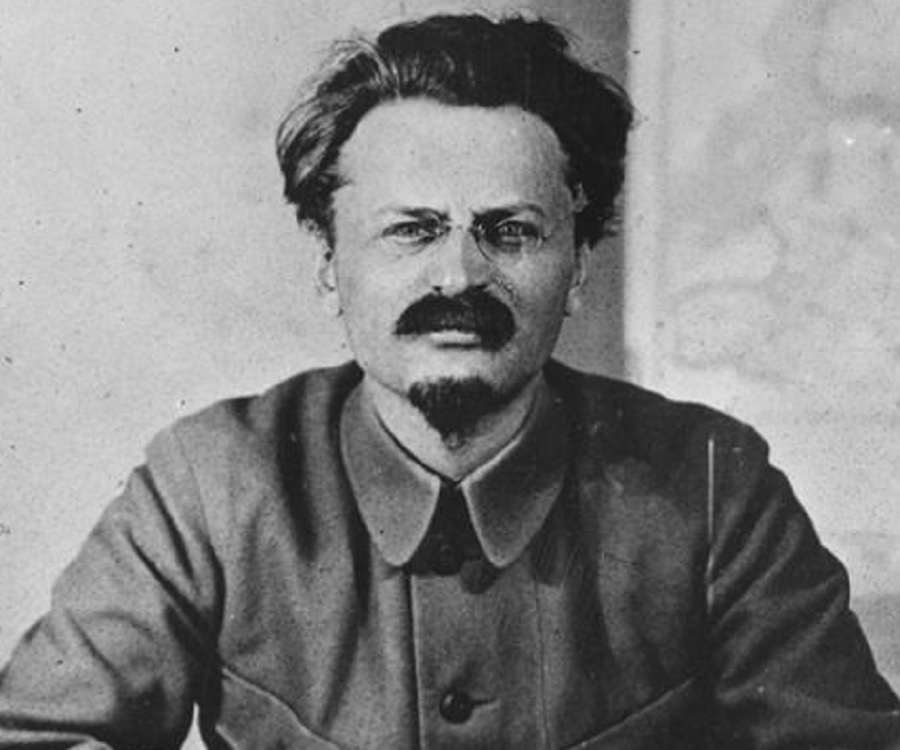

Still, what really complicates his apologism for Napoleon’s empire-building is the author’s frequent citation of Trotsky throughout the book. On the one hand, Mazaheri has many critical things to say about the cult-like political tendency which follows the latter in a chapter where he attempts to “reclaim Trotsky from the Trotskyists” in his defense of the yellow vests.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to separate the movement from the man himself and the repeated references have unintended implications for Mazaheri’s re-examination of Napoleon. In particular, they raise questions over the age-old internal debate on the left over Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution versus the concept of “socialism in one country” that was adopted as Soviet policy following his expulsion.

After all, the former tactic was rejected by the Comintern, as were Trotsky’s previous efforts as war commissar to oppose the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and continue Moscow’s participation in World War I in the hopes of inciting socialist revolutions in Western Europe.

In fact, his ideas can arguably be understood as a conceptual basis for the expansionism of the neo-conservative movement, the founders of which were notably former American Trotskyists in the 1930s. From that point of view, if Napoleon were truly committed to the ideals and principles of the revolution through military conquest, he could be interpreted as having waged a ‘permanent revolution’ of his own.

It is on that same politically confused basis that Mazaheri also makes several historically inaccurate claims about the failure of the Popular Front strategy being responsible for the rise of fascism, instead of where the blame more likely falls on the disruptions by the Fourth International and the treachery of social democracy.

The truth is there is as much evidence to support the view that Napoleon was a child of the Age of Enlightenment who championed the education system and religious freedom as there is to demonstrate he was an authoritarian military strongman who enlarged the French Empire by seizing territories. It is also possible to assert that the principles of socialist democracy were still in their infancy and perhaps it is unfair to judge his entire political legacy with the benefit of hindsight, as Mazaheri puts forward.

Then again, in the case of Louis-Napoleon, Marx happened to be living in Paris in 1851 and witnessed the revolution he co-opted first-hand. However, what is certainly true is the crucial point made overall which is that, throughout history, whenever strong leaders have used their power to do good things, they are often demonized by the status quo only to be redeemed later, regardless of whether it applies to Napoleon. This is in keeping with prior work by the Press TV correspondent who previously penned a passionate defense of the Islamic socialist model in Iran, as flouting such predetermined narratives on the Western left is his modus operandi.

Yet, if there is any figure who has been unjustly slandered by mainstream historians from the French Revolution, that distinction would apply much more so to Maximilien Robespierre than Napoleon. Surely, Macron would not dare lay a wreath at the Jacobin leader’s tomb or commemorate the anniversary of his death as was given on the bicentenary marking the Emperor of the French’s passing in exile, nor does Hollywood have any plans to portray him in an epic blockbuster.

Even though it was under Robespierre, whom Lenin regarded as a “Bolshevik avant la lettre,” when slavery was abolished in the French colonies, liberal historians have always dismissed his contribution as purely that of a bloodthirsty despot, perhaps even more so than Napoleon.

Mazaheri and his readers should turn to the Italian Marxist philosopher Domenico Losurdo’s work, especially War and Revolution: Rethinking the 20th Century and Liberalism: A Counter-History. In their respective polemics, Losurdo and Mazaheri actually share a frequent ideological target in Edmund Burke, the philosophical founder of modern conservatism known by his work Reflections on the Revolution in France, which denounced 1789 on the basis of the Terror while whitewashing equivalent political violence of the English and American Revolutions. However, Losurdo sharply differs on Napoleon and elucidates an important point where the military commander and Robespierre diverged:

“It is hard to believe that the Jacobin leader would have been able to recognize himself in Napoleon. In the course of his controversy with the Girondins, he not only vigorously rejected the idea of exporting revolution, but also warned revolutionary armies against emulating the fatal course of Louis XIV’s expansionism…It might be said that Robespierre legitimized the anti-Napoleonic war in advance.”

While there may be quibbles about his presentation of French political history, Mazaheri’s grasp of the country’s current predicament could not be more on the mark. The timing of the release of the book could also not be better because, like the yellow vests, the millions of pension reform opponents filling the streets of France today are still trying to fulfill the demands of 1789, storming the offices of BlackRock like the Bastille. Or, at the very least, preserving what remains of social democracy in France from Macron’s shock therapy.

Each time the working class has tried to take matters into their own hands, its revolt has been brutally suppressed by those in power, only to be reignited later. By including quotes throughout the book from personal interviews with yellow-vested Parisians, Mazaheri shows how the grievances of ordinary people remain the same today, reading like excerpts of dialogue straight out of scenes from filmmaker Peter Watkins’ dramatization of La Commune.

Macron’s authoritarianism, along with the unelected bureaucracy in Brussels, has revealed the true ugly face of Western liberal democracy that can only continue to exist under state violence and dictatorial rule, as it has ever since tens of thousands of communards were murdered in 1871. As Marx wrote in The Civil War in France:

“Working men’s Paris, with its Commune, will be forever celebrated as the glorious harbinger of a new society. Its martyrs are enshrined in the great heart of the working class. Its exterminator’s history has already nailed to that eternal pillory from which all the prayers of their priest will not avail to redeem them.”

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Max Parry is an independent journalist and geopolitical analyst based in Baltimore.

His writing has appeared widely in alternative media and he is a frequent political commentator featured in Sputnik News and Press TV. He also hosts the podcast “Captive Minds.”

Max can be reached at maxrparry@live.com.