Few People Know Who Maurice Tempelsman Is Despite the Outsized Influence That He Has Played on U.S. Foreign Policy in Africa

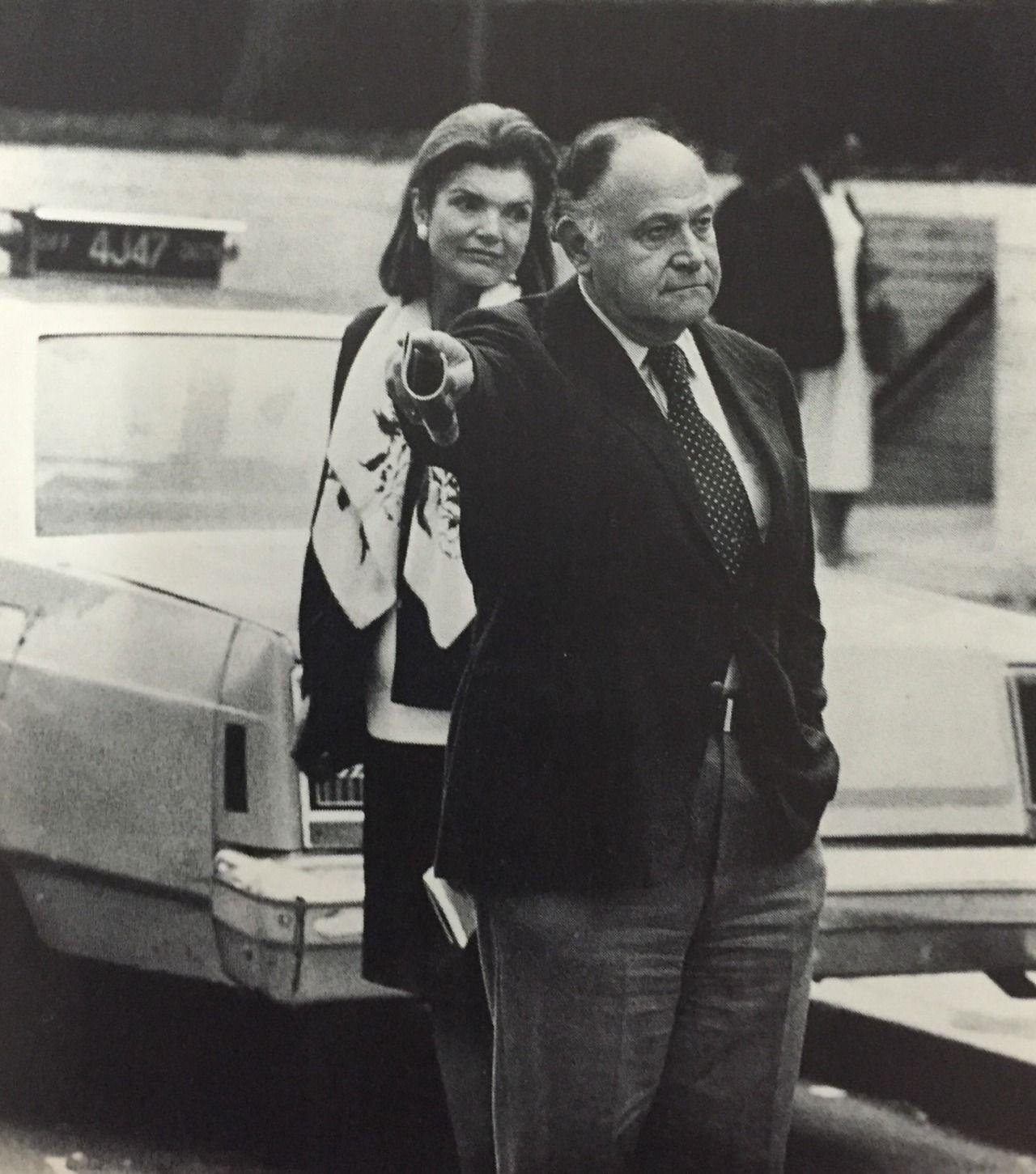

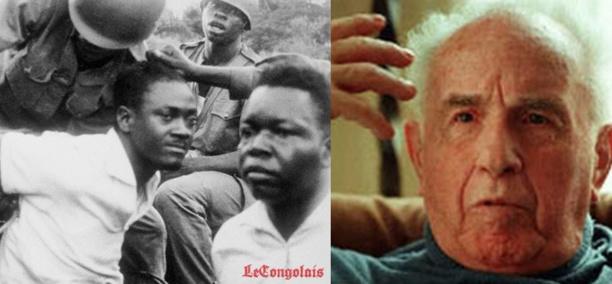

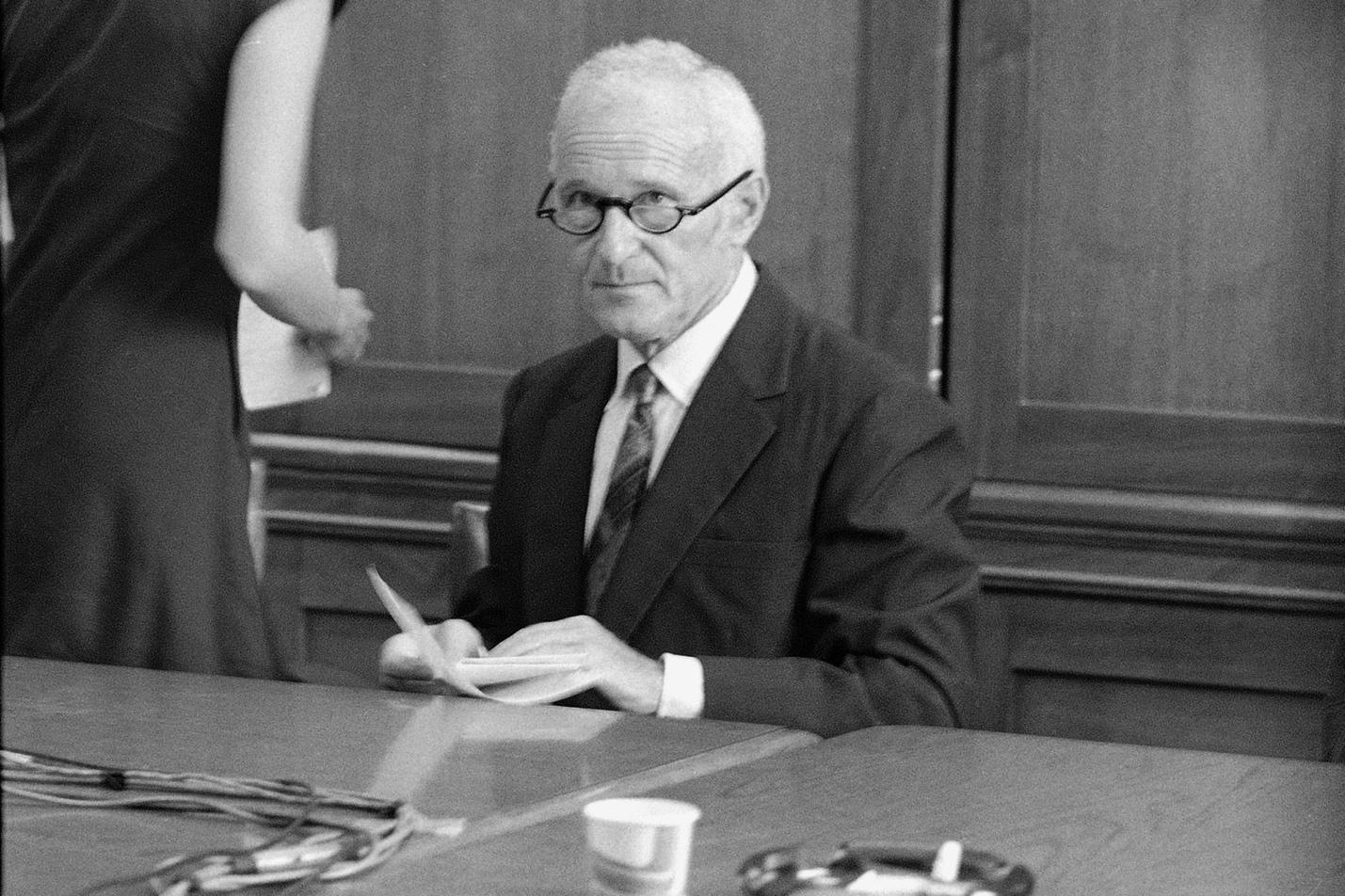

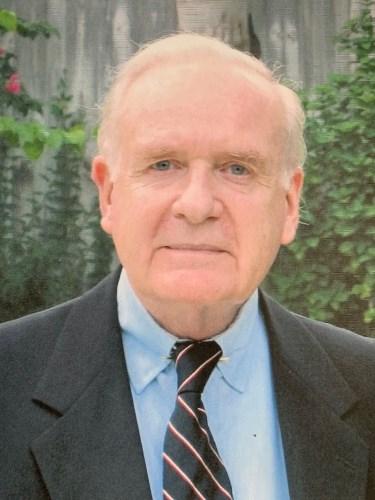

Maurice Tempelsman is a billionaire Democratic Party power broker and donor in his 90s who is chairman of the board of directors of Lazare Kaplan International Inc. (LKI), the largest diamond company in the U.S., and partner in Leon Tempelsman & Son, which has lucrative mining interests throughout Africa.

Born in Antwerp, Belgium, Tempelsman persuaded the U.S. government in 1950 to stockpile African diamonds for industrial and military purposes, with him as middleman.

Four decades later, Templesman accompanied Bill Clinton on a trip to Central Africa where Clinton expanded U.S. support for the Rwandan and Ugandan governments as they invaded the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in order to plunder its diamond and mineral wealth.

Tempelsman also developed a plan for Angola that would bring the right-wing party, UNITA, into the government and allow his companies to bring U.S.-made deep mining equipment into the country and then market the stones that were mined.[1]

Tempelsman’s deep intelligence ties were reflected in his serving as a chairman of the Africa-America Institute, a CIA front involved in propaganda and bringing African leaders to study in the U.S., and director of the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI), an adjunct of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), which finances pro-U.S. leaders around the world whose political platform resembles that of the Democratic Party and will serve U.S. foreign policy objectives.

After Templesman was discovered to have plotted a coup in 1961 against Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, where he had invested in diamond mines, George Ball described Templesman to McGeorge Bundy as “a rather dubious fellow…smooth, soft-spoken..a manipulator,” who had been a generous donor to the Republican Party during the Eisenhower administration but had now emerged as a “Democrat and great friend of the New Frontier.”[2]

In the Congo, Tempelsman cultivated close ties with Joseph Mobutu, the DRC ruler from 1965 to 1998 who gave De Beers—which Tempelsman worked closely with—access to the DRC’s uncut diamonds. Mobutu helped Tempelsman to become a millionaire many times over, as the two shared ownership interests in Zaire’s two main diamond mining concerns, MIBA and Britmond, and Mobutu helped Templesman gain ownership stakes in the Tenke Fungurume Mining Company, a major copper mining firm which Tempelsman had helped form.[3]

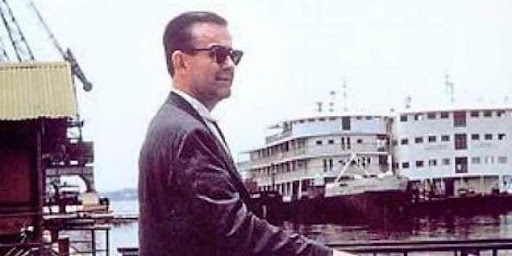

According to a 1979 Washington Post article, Tempelsman’s influence on U.S. policy was apparent in his ability to vet the U.S. ambassadors to the Congo.[4] During the 1960/61 Congo crisis, he reportedly “worked hand in glove with the CIA Station in Congo,” according to political scientist David Gibbs.[5] This close working relationship was evident when he hired Larry Devlin, the CIA’s station chief in Congo from 1960 to 1967, to work for him after Devlin left the CIA (if he ever did).[6]

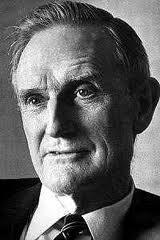

Devlin was a key figure in the January 1961 assassination of the DRC’s first Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, a Pan-Africanist who wanted to strengthen the power of the DRC’s central government and assert national control over the DRC’s rich mineral wealth.[7]

Stuart A. Reid has recently published The Lumumba Plot: The Secret History of the CIA and a Cold War Assassination (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2023) that received glowing reviews in establishment media outlets like The Atlantic and The New York Times.

Incredibly, Tempelsman is nowhere mentioned in the book except in a line at the end where Reid mentions that he hired Devlin after Devlin left the CIA. Several other books have suggested that Tempelsman was key to engineering the coup against Lumumba after he pledged to return Congo’s diamond wealth to the Congolese people.[8]

Reid is an executive editor of Foreign Affairs, the in-house journal of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), Wall Street’s think tank, which has been promoting an imperialist U.S. foreign policy since its founding in 1921.[9]

Tempelsman is a member of the CFR, so his omission from Reid’s book is predictable.

A reasonable question, then, is why a CFR-connected writer would take on a sordid episode in the CIA’s history. The apparent answer is that Reid’s book is what is known in Agency parlance as a “limited hangout” whose central purpose is damage control.

In other words, the U.S. foreign policy establishment and CIA are willing to admit to some wrongdoing that has already been exposed, though obscure the motive underlying the criminal conduct and attempt to create the impression that the U.S. is not doing such bad things anymore.

Significantly, Reid omits the CIA and other U.S. government agencies’ support for the Rwandan-Ugandan invasions of the DRC in the 1990s and 2000s, resulting in grave war crimes and plunder of the DRC’s rich mineral resources, in a stark continuity from Lumumba’s day.

CovertAction Magazine reported on the recent visit of Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines to the DRC at a time when Rwanda has embarked on a renewed offensive in eastern Congo that the U.S. was supporting.

So what better time to bring out a book that sanitizes the past and suggests that, while the U.S. may have done some wrong, it was now cleaning up its act and should go on with its work of trying to bring “stability” and “democracy” to a troubled region?

Lumumba’s Rise and Fall

Reid opens his book with a description of a police raid in the Belgian countryside of the home of Godelieve Soete, whose father Gerard was a Belgian colonial police officer who had helped dispose of Lumumba’s body by dissolving part of it in acid.

Soete took as a trophy one of Lumumba’s teeth, which he stored in a box that he left with his daughter, along with spent bullets used in Lumumba’s killing.

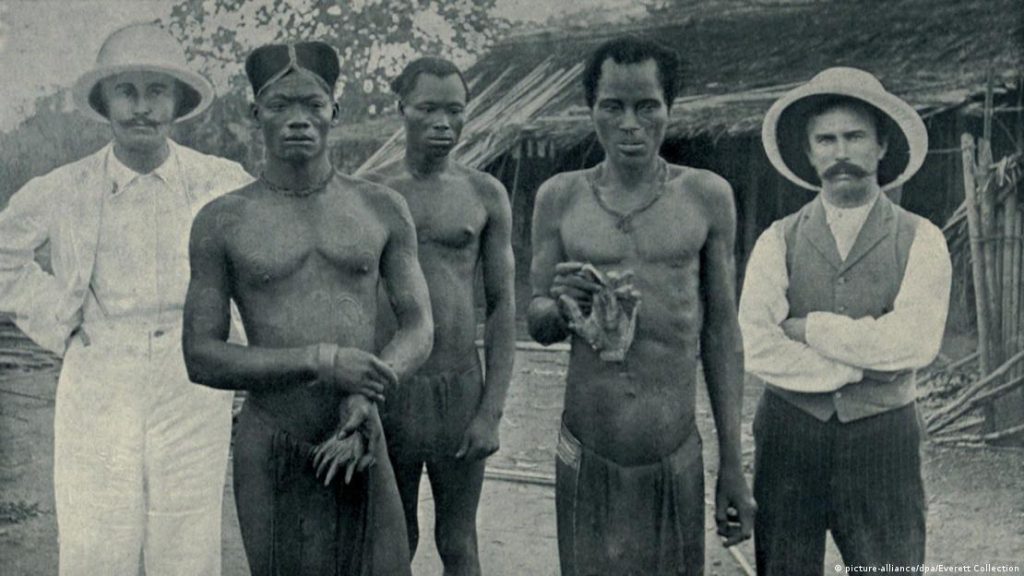

Lumumba’s death fit a pattern of cruelty endemic to Belgian colonialism in the Congo.

After Belgian King Leopold established personal sovereignty over the Congo in the 1880s, Congolese villagers who did not meet rubber quotas had their huts burned and limbs hacked off.

Mass starvation and disease caused the Congo’s population to drop in half from 1880 to 1920, by which time Leopold sold the Congo to Belgium.

Patrice Lumumba was a member of the Batetela tribe, born into humble circumstances in rural Congo, who discovered a talent for oratory while working as a postal clerk and beer salesman in the 1950s.

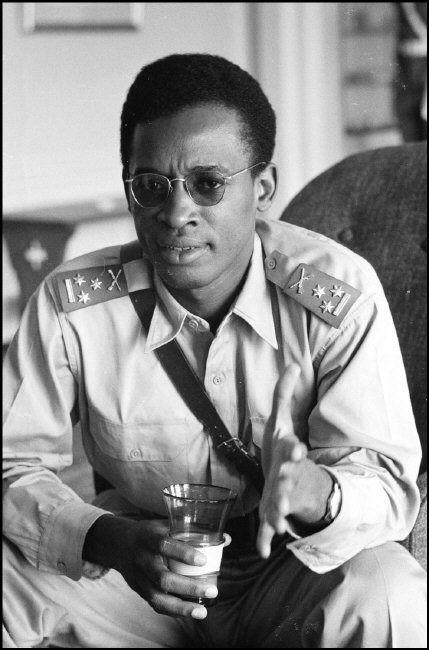

After Lumumba became a leader in the Congolese National Movement (MNC) party, Joseph Mobutu, an army officer and journalist also born into humble circumstances, served as his private secretary.

Reid found evidence to suggest that Mobutu’s treachery was evident as early as 1956 when he was first put on the payroll of Belgian intelligence, which passed on his information to the CIA station in Brussels where Lawrence Devlin worked.[10]

After Lumumba traveled to Conakry and attended a Pan-African conference in Accra hosted by Ghanaian leader Kwame Nkrumah, he became enthralled by the idea of African unity.

Belgian and American consular officials focused on Lumumba’s arrest on embezzlement charges in their negative characterizations of him, though Lumumba had sold company goods on the black market because he was not being paid adequately and had a young family to support and later repaid his debt.[11]

CIA Director Allen Dulles called Lumumba an “irresponsible embezzler susceptible to bribery and communist influence,”[12] obscuring the real reasons that the U.S. government opposed him.[13]

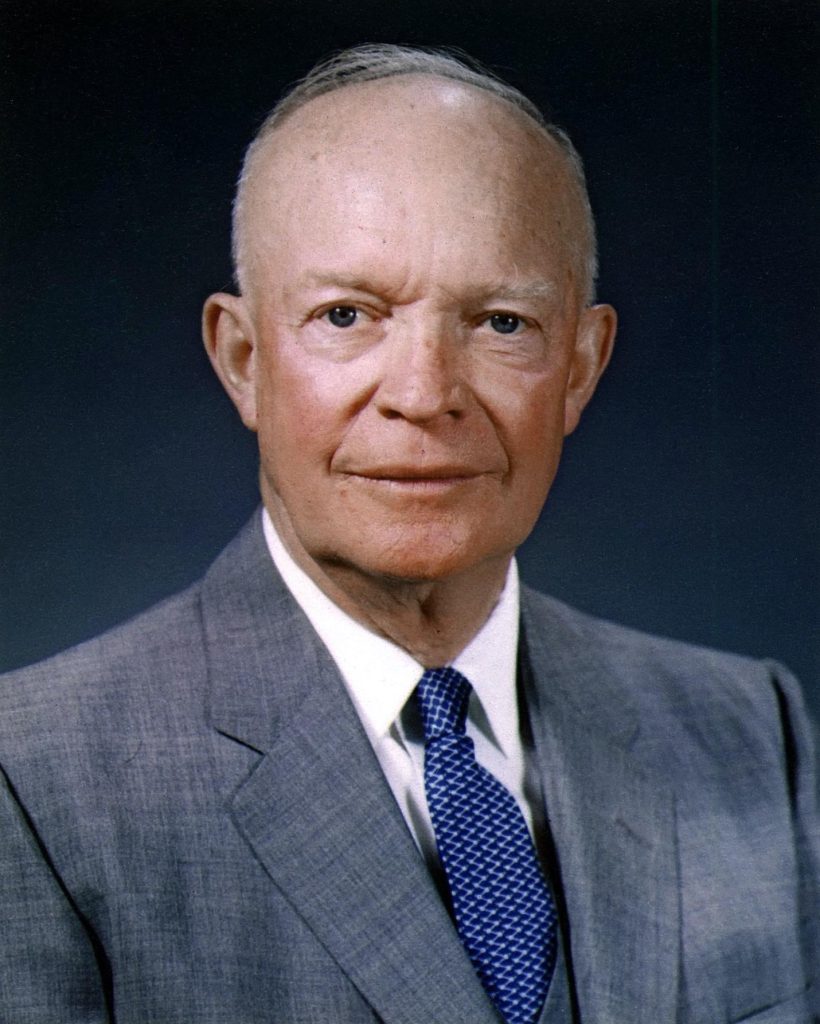

The racism of U.S. officials was further apparent when Dulles told U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower that some 80 political parties were vying for political power in the Congo,

Eisenhower quipped that he did not realize so many people in the Congo could read (in fact, Congo’s literacy rate, at 40%, was among the highest in Africa, with access to primary school being widespread). Eisenhower also agreed with an aide who said that “many Africans still belonged in the trees.”[14]

At the DRC’s independence ceremony, Lumumba earned the ire of Belgian authorities when he gave a powerful speech denouncing Belgian colonialism in front of King Baudouin.[15]

After he took office, Lumumba had to deal with an army mutiny and secessionist movement in the mineral-rich Katanga province backed by Moise Tshombe, a “walking museum of colonialism,” along with Belgium and right-wing elements in the U.S.

U.S. diplomats accused Lumumba of waging a genocide against ethnic Baluba in Katanga and contributing to the DRC’s implosion through his misrule. He was further accused of being a pawn of the Soviet Union even though Reid’s account shows that Lumumba was an independent nationalist.

The UN played a largely dishonorable role in the Congo crisis of 1961 by doing little to protect Lumumba and effectively siding with the Western powers.

The CIA had poured money into anti-Lumumba candidates in Congo’s first election, favoring Mobutu whom Lawrence Devlin, Mobutu’s adviser, described as “an extremely intelligent man…with great potential.”[16]

Early in Lumumba’s tenure as Prime Minister, Devlin coordinated anti-Lumumba riots by paying the protesters, in collaboration with a Belgian plantation owner.[17] Devlin and his CIA colleagues also made payments to Mobutu to ensure the loyalty of key army officers and the support of legislative leaders, forged contacts with labor unions and student groups, subsidized newspapers and initiated “black” broadcasts from a radio station in Brazzaville across the border to encourage a revolt against Lumumba.[18]

Orders for Lumumba’s assassination came directly from President Eisenhower. Devlin was put in touch with the CIA’s “Doctor Death,” Sidney Gottlieb, who traveled to the Congo under the name of Sidney Braun. Gottlieb showed Devlin a special poison he had concocted for Lumumba that would not show up in any autopsy.[19]

The CIA’s plan for killing Lumumba was never implemented because Mobutu and Tshombe’s forces and the Belgians got to Lumumba first.

Nevertheless, Washington was deeply complicit in Lumumba’s death: It pressured UN troops to stop protecting him so that he could be kidnapped and ignored pleas by Lumumba’s supporters to secure his release.[20] Devlin further gave the green light for Lumumba’s transfer into the arms of Moise Tshombe whose forces murdered him in the company of their Belgian advisers.[21]

Afterwards, a CIA agent drove around Elizabethville (Lubumbashi) with Lumumba’s body in the trunk. The CIA in turn worked to ensure that his supporters were politically marginalized and the Johnson administration supported a large-scale covert military operation against them after they took up arms against the corrupt Mobutuist state.

Misrepresentations and Sins of Omission

Reid’s book provides a cogent summary of political developments in the DRC that points to the CIA’s deep complicity in Lumumba’s assassination.

But the book also has some clear misrepresentations and biases.

Firstly, it appears to underplay the CIA’s direct role in Lumumba’s death, relying too much on Devlin’s account, which in the words of historian Susan Williams, was a “tissue of lies.”

Reid entirely leaves out the fact that a CIA linked airline managed by a CIA front, Air Congo, was used to transport Lumumba from Kasai where he was captured to Leopoldville and then Katanga where he was killed.[22]

Reid also leaves out the existence of a CIA operation involving U.S. Air Force personnel flying French fighter jets in support of Moise Tshombe’s forces as a counterweight against Lumumba.[23]

Reid’s depiction of Lumumba too often echoes policy makers in being negative.

Reid makes it seem that Lumumba was a failure as a leader of the Congo when, in fact, he faced insurmountable crises, was a man of integrity, and had a progressive vision for his country to which Reid pays short shrift.

Reid barely touches on Lumumba’s Pan-African ideals, and connection to Ghanaian leader Kwame Nkrumah, a titan in the Pan-African movement who was overthrown in a CIA-backed coup in 1966. Reid furthermore does not discuss how Lumumba’s attempts to assert local control over Congo’s economy made him a target for a regime-change operation similar to the ones undertaken by the CIA in Guatemala, Cuba and Iran and in countries like Venezuela and Nicaragua today.

Reid seems critical of Lumumba’s attempt to suppress the Katangan secessionists, when the latter were financed by the colonial powers and their agents with the goal of weakening the Congo.

Additionally, Reid repeats a rumor that may have been spread as part of CIA disinformation—that Lumumba requested a white blond when he visited New York—that reinforces the stereotype of Africans’ supposedly ravenous sexuality.

The Lumumba Plot’s function as a “limited hangout” is evident when Reid dismisses as “conspiracy theory” the suggestion that UN Secretary-General Dag Hammerskjöld’s plane went down because it was sabotaged by hardline supporters of Katangan secession in collaboration with the Belgian or other Western intelligence services. Susan Williams’ study, Who Killed Hammerskjöld?: The U.N., the Cold War and White Supremacy in Africa (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), provides substantial evidence for this, which Reid dismisses.[24]

When discussing Ralph Bunche, a U.S. State Department envoy to the UN and former Office of Strategic Services (OSS) operative, Reid acknowledges his bias against Lumumba, whom Bunche compared to Hitler, but fails to note how Bunche was trying to cut a deal with Tshombe, which Lumumba figured out.

Reflective of an elitist contempt for left-wing guerrilla movements, Reid is far too disparaging of the pro-Lumumba rebels leading the so-called Simba revolt against Mobutu’s government after Lumumba’s assassination, failing to articulate their grievances or vision for social change, as well as the brutal way in which the rebellion was suppressed.[25]

Reid could have generally drawn on more Congolese voices to help convey to readers just how catastrophic the CIA’s covert manipulation was and how it set the stage for American predation on a massive scale.

For all the praise heaped on Reid’s book in establishment media, it breaks little new ground over previous accounts of U.S. intervention and ignores the pivotal role played by figures other than Lawrence Devlin in coordinating the U.S. regime-change operation against Lumumba.

Reid claims to have interviewed Frank Carlucci, Deputy CIA Director under Jimmy Carter and Defense Secretary under Ronald Reagan who was Second Secretary in the U.S. Embassy in the Congo at the time Lumumba was killed, but does not discuss at all his role in the anti-Lumumba plot, which appears to have been significant.

Reid also leaves out the background of the U.S. ambassador to Belgium from 1959 to 1961 that called for Lumumba’s assassination, William Burden, who headed a CIA front organization, and was director of American Metal Climax, a mining firm with heavy investment in Congo.[26]

Reid attributes U.S. criminal conduct in Congo to paranoia about the spread of communism in the Cold War, underplaying the mining interests and economic imperatives driving U.S. foreign policy.[27]

In the book, Thy Will Be Done: The Conquest of the Amazon: Nelson Rockefeller and Evangelism in the Age of Oil, Gerard Colby and Charlotte Dennett emphasize how, when Lumumba stated in a meeting that Congo under his leadership was now a sovereign country and that Belgium did not produce uranium and would not have a monopoly anymore, and that the U.S. would have to negotiate its own agreement, the Americans, “all of whom represented powerful financial interests, looked at one another and exchanged meaningful smiles.”[28]

Meaning that then and there, Lumumba’s goose was cooked.

For all the resources and research assistance that Reid had, curiously, he does not reference Colby and Dennett’s important study in his bibliography, nor other key books, like Wayne Madsen’s Genocide and Covert Operations in Central Africa 1993-1999, which takes the story of CIA intervention in Congo forward—something Reid refuses to do.

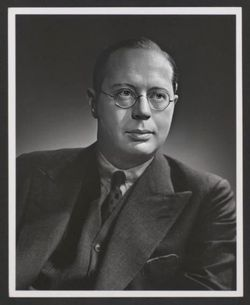

Besides Tempelsman, Reid fails to discuss Harold K. Hochschild, a senior executive in American Metal Climax Inc., which owned mines on the Congo-Zambia border, and financier of the Africa-America Institute, the CIA front organization for which Tempelsman was chairman.[29]

Born in 1892 to a Jewish family in New York that owned the American Metal Company (AMCO–precursor to American Metal Climax), which purchased interests in two of the world’s largest copper mines in Africa and provided 10 percent of U.S. uranium production, Hochschild was a prominent Democratic Party contributor who helped finance Adlai Stevenson’s 1956 presidential campaign.[30]

According to journalist Keith Harmon Snow, Hochschild was also close with Allen Dulles whose law firm, Sullivan and Cromwell, did legal work for AMAX, which was formed in 1957 after the American Metal Company merged with Climax Molybdenum Company (AMAX was later incorporated into Phelps-Dodge which was itself acquired by Freeport McMoRan).[31]

Both Tempelsman and Hochschild fashioned themselves anti-colonial liberals supportive of African independence movements but were shrewdly intent on manipulating postcolonial developments in Africa so they could grow their fortunes.

Their opposition to colonialism stemmed largely from their interest in breaking the colonial powers’ monopoly over mining and other industries and in getting the post-colonial governments to open their economies to American investors and to promote free trade.[32]

In the case of the Congo, Tempelsman opposed Katanga secession (which in the U.S. was a cause of the far right) and was happy to see Belgium relinquish its power so an opening could develop for him to take over its mining interests.[33]

Tempelsman had very close ties with John F. Kennedy, supporting him in the 1960 election and arranging a meeting between Kennedy and Harry Oppenheimer, the famous South African investor. He employed Kennedy aide Theodore Sorenson, whom Mobutu hired to represent the Congo in a dispute with Belgian mining companies, as a lawyer, and Kennedy’s Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara as a lobbyist.[34]

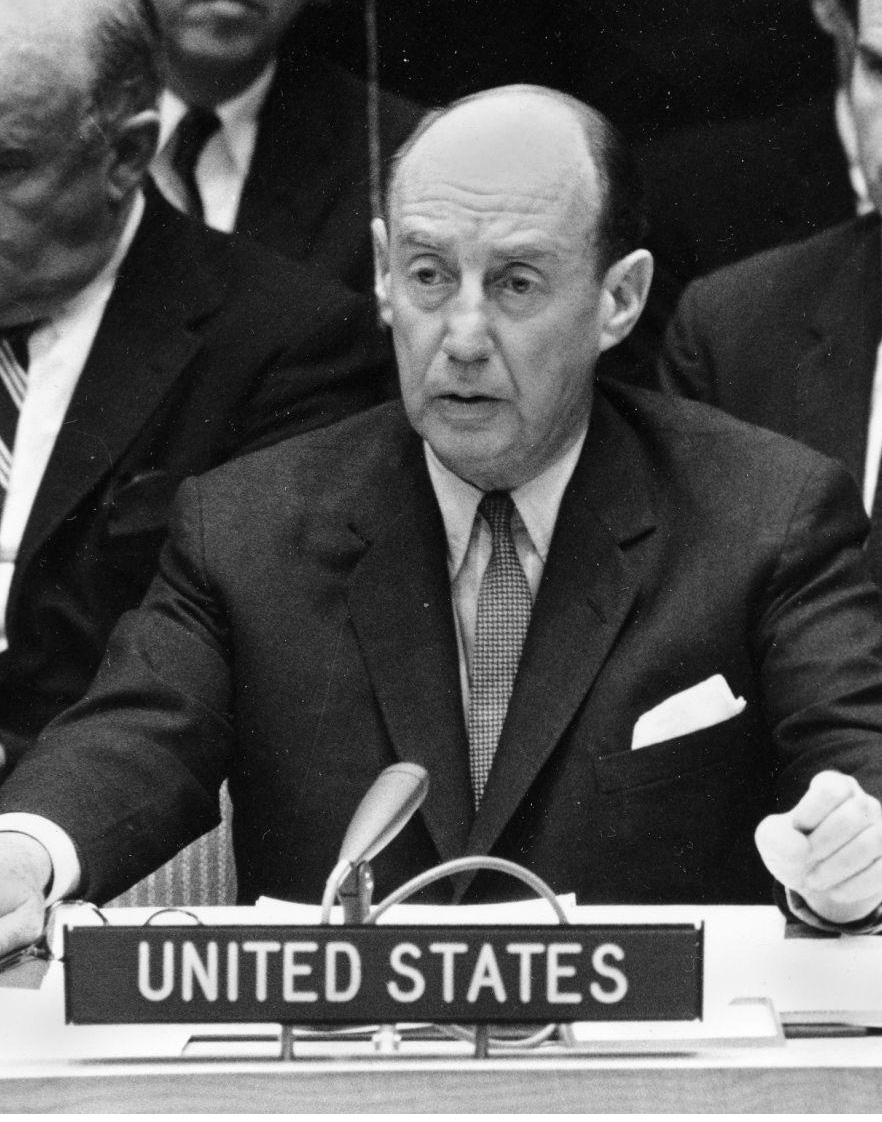

Tempelsman’s influence on U.S. policy was levered in part through Adlai Stevenson, the U.S. Ambassador to the UN in 1961 and Democratic Party presidential candidate in 1952 and 1956, who had been his lawyer.[35] A friend of Harold Hochschild who counted American Metal Climax among his company’s clients, Stevenson helped Tempelsman to successfully lobby for the scheme by which the U.S. government purchased industrial diamonds from the Congo to be used in the government’s strategic stockpile, with Tempelsman acting as a middleman.[36]

George H. Wittman also operated as a Tempelsman agent in Congo circa 1959-1960 onward and was on the payroll of the CIA, working under Devlin.[37]

The Rockefellers were another major driver of U.S. foreign policy in the Congo that Reid leaves out. They were shareholders in Tanganyika Concessions Limited, which owned copper and uranium mines in Katanga, financed Templesman’s Congo ventures, and owned stock with the Guggenheim group in Forminière, a Belgian mining operation in Kasai province, directly north of Katanga.[38]

Additionally, the Rockefellers acquired in full, or in part, a textile plant, an automobile distributor operation, a pineapple processor, a metal can producer, and a mineral prospecting firm in the Congo. The Rockefeller-controlled Socony-Vacuum Oil Company further owned service stations and gasoline storage terminals worth a total of twelve million dollars.[39]

The Rockefellers had direct influence over the Kennedy administration through Secretary of State Dean Rusk, the former head of the Rockefeller Foundation, and Treasury Secretary C. Douglas Dillon, a close friend of John Rockefeller III who was chairman of the Rockefeller Foundation from 1972 to 1975 and director of a major Wall Street investment bank, Dillon, Read & Co., which in 1958, floated a $15 million bond issue for the Belgian Congo colonial government.[40]

Dillon was also an investor with the Belgians in Laurance Rockefeller ‘s Congolese textile mill, Filatures et Tissage Africains, and in another of Laurance ‘s holdings, Cegeac, which imported automobiles into the Congo.[41]

As the number two official in the State Department, Dillon met directly with Lumumba when he visited the U.S., as Reid, failing to note his Rockefeller connection, points out, and told the 1975-1976 Church Committee investigating CIA abuses that he found Lumumba “psychotic” and “impossible to deal with.”[42]

The Rockefellers were key financiers of CIA-front organizations like the Africa-America Institute that helped manipulate post-colonial political developments in the Congo, among other African nations (along with nations in Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Latin America).[43]

Reid ought to have explored the importance of the Rockefellers, Hochschild, Tempelsman and the Africa-America Institute, given his focus on the CIA, along with the role that other corporate-financed foundations played in shaping U.S. foreign policy in Congo.

However, Reid’s paymasters at the CFR would not tolerate the latter kind of probing investigation, since it would help to expose the CFR and U.S. foreign policy apparatus for what it really is—a cover for wealthy oligarchs intent on plundering Africa and other regions around the world for their personal enrichment.

Instead, what the CFR wants is the kind of sugarcoated history Reid delivers that skirts the political-economic imperatives that continue to drive U.S. foreign policy in Central Africa and cause endless suffering for the Congolese people.

- The author would like to thank Keith Harmon Snow for his help in writing this review.

-

Susan Schmidt, “DNC Donor With Eye on Diamonds,” The Washington Post, August 2, 1997, A1. Tempelsman had visited the Clinton White House at least ten times between 1993 and 1997 and met privately with Hillary Clinton, receiving a lot of bang for the $145,000 he donated to the Democratic Party during the 1996 election cycle. Allegedly, Tempelsman used his influence over Anthony Lake, Clinton’s National Security Adviser, to secure a loan from the Export-Import Bank of the United States that allowed him to bring U.S.-made deep mining equipment into Russia. ↑

-

Susan Williams, White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa (New York: Public Affairs, 2021), 446, 452. ↑

-

Leon Dash, “U.S. Businessman Plays a Key Role As Aide to Mobutu,” The Washington Post, December 31, 1979. A diplomat who knew Tempelsman and Mobutu described their relationship as “very personal” and said that both were reaping substantial earnings from the gem diamond trade. Tempelsman put together an international combine that owned 80% of the world’s richest copper and cobalt lode, lying under 900 square miles of savanna just outside Kolwezi, in Zaire’s mineral-rich Shaba Province. See also David N. Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention: Mines, Money, and U.S. Policy in the Congo Crisis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991). ↑

-

Dash, “U.S. Businessman Plays a Key Role As Aide to Mobutu.” Tempelsman is believed to have helped Mobutu with advice on political matters in Washington. Mobutu’s lobbyist in Washington in the 1970s was William Blair, a one-time law partner of Democratic Party presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson, who was Tempelsman’s lawyer. ↑

-

Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 110. ↑

-

Devlin worked directly for Tempelsman from 1974 to 1987. Devlin’s assistant was Colonel John Gerassi, who formerly headed the U.S. military mission to Zaire. In effect, Tempelsman was buying access to Mobutu, with whom Devlin was very close and could contact at any time. ↑

-

CIA operative Anthony Poshepny told journalist Douglas Valentine that when Devlin became CIA station chief in Laos in the late 1960s, he would boast that he’d arranged the assassination of Lumumba. Douglas Valentine, Pisces Moon: The Dark Arts of Empire (Walterville, OR: Trine Day, 2023), 173, 174. ↑

-

These books include: Janine Roberts, Glitter and Greed: The Secret World of the Diamond Cartel (Disinformation Books, 2007), 177-85; Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention; and Wayne Madsen, Genocide and Covert Operations in Africa 1993-1999 (New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1999). ↑

- See Laurence H. Shoup and William Minter, Imperial Brain Trust: The Council on Foreign Relations & United States Foreign Policy (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977); Laurence H. Shoup, Wall Street’s Think Tank: The Council on Foreign Relations and the Empire of Neoliberal Geopolitics, 1976-2019 (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2019). The first honorary president of the CFR, Elihu Root, was a staunch supporter of the U.S. colonization of the Philippines and U.S. intervention in World War I.

-

Stuart A. Reid, The Lumumba Plot: The Secret History of the CIA and a Cold War Assassination (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2023), 73. ↑

-

Reid, The Lumumba Plot, 17. ↑

-

Reid, The Lumumba Plot, 102. ↑

-

Dulles also referred to Lumumba as a “Castro or worse.” ↑

-

Reid, The Lumumba Plot, 102. The conservative National Review magazine was even more blatantly racist than Ike, referring to Lumumba as “a cheap embezzler, a schizoid agitator (half witch-doctor, half Marxist), an opportunist ready to sell out to the highest bidder, ex-officio Big Chief Number One of a gang of jungle primitives strutting about in the masks of Cabinet Ministers.” ↑

-

Reid, The Lumumba Plot, 119, 120. Lumumba stated powerfully that, under Belgian colonial rule, the Congolese people “suffered contempt, insults, and blows, morning, noon and evening because we were Negroes. Who can forget that a Black was addressed by the familiar tu, certainly not as a friend, but because the formal vous was reserved for whites alone? We have known that our lands were seized in the name of the supposedly legal texts that recognized only the rights of the strongest. We have known that the law was never the same for whites and blacks, accommodating for one, cruel and inhumane for the other…We have known that in the cities, there were magnificent houses for whites and decrepit huts for Blacks, that Blacks could not enter so-called European movie theaters, restaurants, and stores, and that Blacks would travel in the hold of a riverboat underneath the whites in their luxury cabins. Who can forget, finally, the shootings in which so many of our brothers perished, or the dungeons where those who did not want to submit to the oppressive and exploitative regime were brutally thrown?” ↑

-

Reid, The Lumumba Plot, 87. ↑

-

Reid, The Lumumba Plot, 269, 270. ↑

-

After Lumumba was ousted, the CIA, operating through a Liechtenstein front company called Western International Ground Maintenance Operation (WIGMO), organized an “instant Air Force” for the Congolese government. ↑

-

Reid, The Lumumba Plot, 317. ↑

-

Reid, The Lumumba Plot, 331. Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah appealed to President John F. Kennedy; Kennedy ignored it (p. 391). ↑

-

Reid, The Lumumba Plot, 428, 429. ↑

-

Williams, White Malice, 409, 410. Air Congo is nowhere listed in Reid’s books index. Reid lists Susan Williams’ book White Malice in his bibliography but either did not give the book a close or full read or willfully omitted the information she presents about Air Congo, among other things. Williams, it should be noted, is a first rate scholar who is a senior research fellow at the School of Advanced Study, University of London. ↑

-

Williams, White Malice, 410. ↑

-

Williams details for example how Charles M. Southall, a U.S. naval intelligence officer working at the National Security Agency’s (NSA)’s listening station in Cyprus in 1961, linked French fighter jets, which had had gun cannons fitted, flown by U.S. Air Force personnel in Katanga, to Hammskjold’s death. He told a commission of inquiry in 2012 that he had heard the recording of a pilot’s commentary as the pilot shot down Hammerskjold’s DC-6. Williams, White Malice, 414, 415, 417. Southall stated that the recording was chilling as he could “hear the gun cannon firing” and the pilot stating “flames coming out of it. I’ve hit it. Great, or good or something like that, it’s crashed.” Southall said that in his view “there was a CIA unit out there and they had responsibility for refueling the French plane, finding the pilots, coordinating with the Belgian, French mining interests, and it was the CIA unit that ensured that the plane would be shot down.” Southall’s suspicion about the CIA received corroboration when documents with a South-African based mercenary organization stated that “CIA Director Allen Dulles had promised full cooperation with Operation Celeste, a plot to kill Hammerskjold.” The murder of Lumumba was also referenced in the document, with Dulles giving orders that “I want his [Hammerskjold’s] removal to be handled more efficiently than was Patrice Lumumba.” The purported plot in the documents, which have since disappeared, involved placing a bomb on Hammerskjold’s plane, which failed to explode; a pilot was then dispatched to shoot down the aircraft. Williams believes that this pilot or his conduit may have been Urban L. “Ben” Drew, an ace World War II pilot whose covert work in Congo and Vietnam was acknowledged by his son and who was identified in a South African newspaper as a gun runner for Moise Tshombe in 1961 and as being the one rumored to have shot down Hammerskjold’s plane.. ↑

-

See Jeremy Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression: Police Training and Nation Building in the American Century (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), ch. 7 for a summary, and Piero Gleijeses, Conflicting Missions: Washington and Havana in Africa, 1959-1975 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003). Neither of the above cited studies are listed in Reid’s bibliography, indicating that he has not done his homework or disingenuously omitted evidence and works that cast U.S. policy more critically than him. ↑

-

A lifelong friend of Allen Dulles, Burden’s links to the CIA were evident in his being appointed director of the Fairfield Foundation, a CIA front that financed such cultural organizations as the Congress for Cultural Freedom, and to the Board of the Africa-America Institute. Burden was an heir to the Vanderbilt fortune who made substantial contributions to the Republican Party in the 1956 presidential campaign. A strong proponent of biological warfare, he served as Director of Lockheed Martin and of the Council on Foreign Relations, Wall Street’s think tank. Williams, White Malice, 123, 124, 139. ↑

-

Reid also omits the U.S. establishment of a missile base in a remote part of Zaire under Mobutu, another underlying motive for the close relations forged with Mobutu. The missile base was reported on in The CIA and Dirty Work 2: The CIA in Africa, ed. Ellen Ray, William Schaap, Karl Van Meter and Louis Wolf (Secaucus, NJ: Lyle Stuart, 1979). ↑

-

See Gerard Colby and Charlotte Dennett, Thy Will Be Done: The Conquest of the Amazon: Nelson Rockefeller and Evangelism in the Age of Oil (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), 326. ↑

-

For more on Hochschild, see Adam Hochschild, Half the Way Home: A Memoir of Father and Son (New York: Viking, 1988) and Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 120. ↑

-

Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 120; Williams, White Malice, 493. ↑

-

Author interview with Keith Harmon Snow, January 8, 2024. Another director of American Metal Climax, William Burden, an heir to the Vanderbilt fortune who made substantial contributions to the Republican Party in the 1956 presidential campaign, was U.S. ambassador to Belgium at the time of the Lumumba assassination and a bitter foe of Lumumba who openly called for his assassination. Williams, White Malice, 123, 124. In 1957, Burden, who was an influential proponent of biological warfare, was appointed as a public trustee of the Pentagon Institute For Defense Analysis (IDA), a target of protest during the Vietnam War. Burden’s links to the CIA were evident in his referring to Allen Dulles as a “lifelong friend.” ↑

-

See Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention. Tempelsman and Hochschild aligned with the Kennedy administration policy that supported moderate anti-communist, anti-colonial factions and aimed to undermine the socialist and communist left. ↑

-

Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 111. Gibbs spotlights divisions among businessmen and in the Kennedy administration over the issue of Katanga secession. When Mobutu took power, the Kennedy administration (with backing from Tempelsman and Hochschild) supported him in crushing the Katanga secessionist movement. No moral outcry was raised at any atrocities then as there had been when it was Lumumba’s troops fighting there. Tshombe was forced to flee into exile and died in Algiers in 1969 under mysterious circumstances. Police training programs were used by the CIA to beef up Mobutu’s security forces and crush Katangan secession. ↑

-

Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 110, 173. Sorenson’s intelligence connections were apparent in his nomination by Jimmy Carter in 1977 to be CIA Director. John F. Kennedy, Jr., spent a summer working for Tempelsman in Africa. A 1964 National Security Council document referred to Tempelsman as a “heavy contributor in Democratic politics.” He was considered a “kingpin” of state politics in New York, supporting the Eleanor Roosevelt-Herbert Lehman reform group, according to Stephen Weissman. ↑

-

Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 109. ↑

-

Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 109, 110; Williams, White Malice, 91. Tempelsman’s scheme was approved in 1965. Tempelsman later helped finance the editing of Stevenson’s personal papers. ↑

-

Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 109; Williams, White Malice, 93. Wittman was President of G H Wittman Inc., a mining and trading family business which did extensive business in Africa and the Middle East. In 1973, Wittman published an espionage novel A Matter of Intelligence. ↑

- See Colby and Dennett, Thy Will Be Done, 326. ↑

-

Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 67, 182, 189. Templesman and Eisenhower’s Treasury Secretary Robert B. Anderson, who worked for the Rockefeller owned Standard Oil of Indiana, came to act as a broker for the numerous American investors in the Congo, including Morrison-Knudsen and Goodyear Rubber. ↑

-

Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 67. The State Department Africa Bureau’s leading specialist, Deputy Assistant Secretary J. Wayne Fredericks, reportedly an “old CIA man” became a vice president and director of international relations for Chase Manhattan Bank where he probably helped arrange the Congo’s commercial loans. Harlan Cleveland, the Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs, had been an analyst for the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, reflecting the further influence of the Rockefellers on State Department policies. ↑

-

Gibbs, The Political Economy of Third World Intervention, 118. Gibbs emphasizes that Dillon was pro-Belgian and supported Katanga secession. ↑

-

According to Reid, Dillon stated further about Lumumba: “When he was in the State Department meeting, either with me or with the Secretary in my presence, he spoke in a manner that seemed almost messianic in quality. And he would never look you in the eye. He looked up at the sky. And a tremendous flow of words came out. He spoke in French, and he spoke it very fluently. And his words didn’t ever have any relation to the particular things that we wanted to discuss. And it was just like ships passing in the night. You had a feeling that he was a person that was gripped by this fervor that I can only characterize as messianic. And he was just not a rational being.” ↑

-

See Hochschild, Half the Way Home; Williams, White Malice, 91. The Africa-America Institute’s board included Hochschild, Templesman, William Burden, and Dana Creel, later head of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.