I Am Gitmo spotlights the story of an Egyptian man who was incarcerated in notorious torture chamber for a decade after being wrongfully accused of being part of 9/11 plot

Gamel Sadek was living a quiet life as a school teacher in Kandahar in March 2002 when his life was suddenly shattered.

While eating lunch one day with his wife and sons, two Afghan police came to his door and arrested him, taking him to a CIA black site at Bagram Air Base and then to Guantánamo Bay prison in occupied Cuban territory where he was tortured for the next ten years.

The U.S. government alleged that Sadek, an Egyptian who had fought with the mujahadin in the 1980s, was a member of al-Qaeda involved in planning the 9/11 attacks, though never developed any proof of this.

In reality, Sadek was sold out by his neighbor, who was paid a $5,000 bounty by U.S. soldiers under a program initiated by then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.

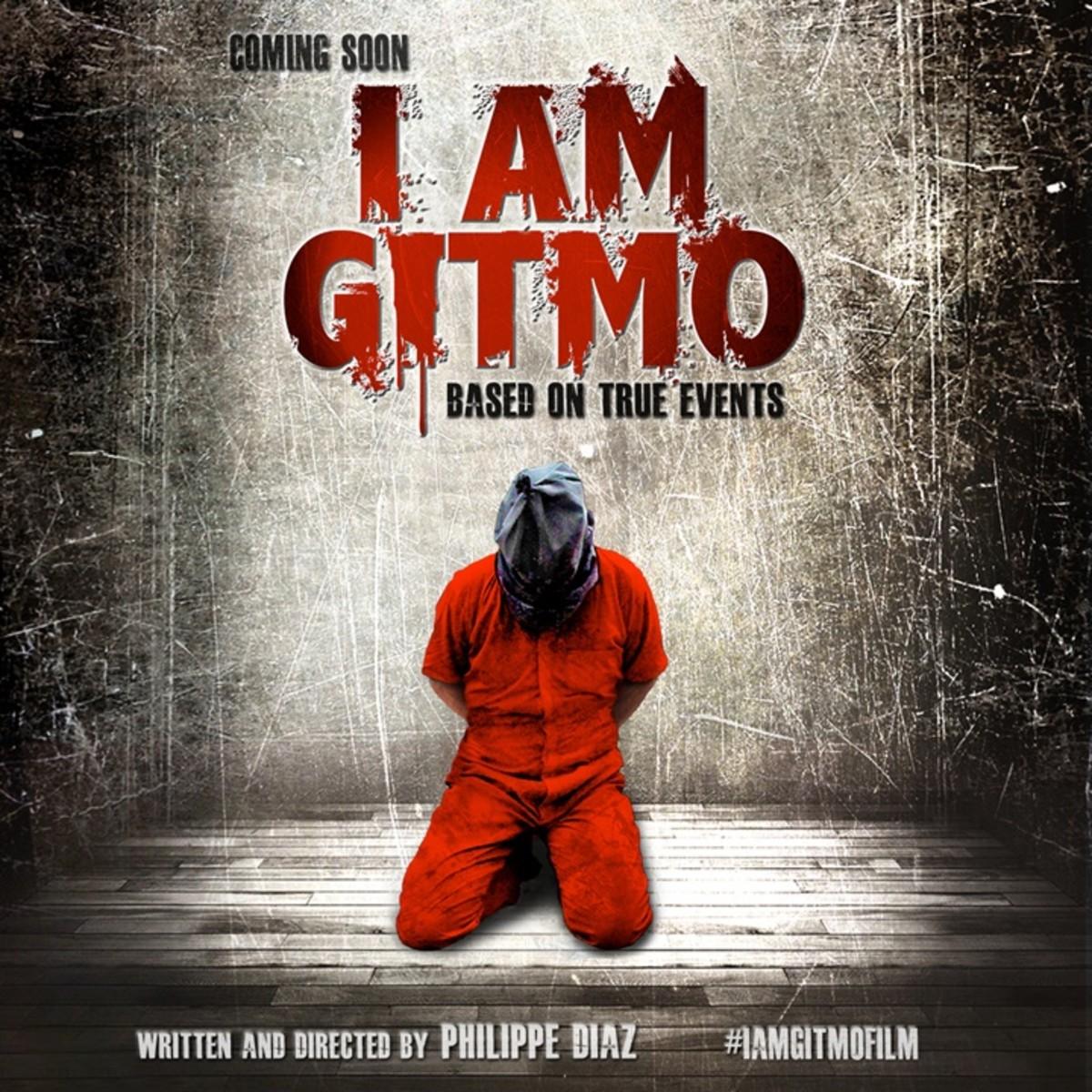

Sadek’s story is spotlighted in the film, I Am Gitmo, written and directed by Philippe Diaz, which won a best actor award at the 2023 Marbella International Film Festival in Spain and the Special Jury Award at the Socially Relevant Film Festival in New York.

Though Sadek is not real, his is the story of the overwhelming majority of Guantánamo Bay inmates. Eighty-six percent of them were sold to American troops in a bounty program modeled after the Phoenix Program in Vietnam, which resulted in the torture and deaths of tens of thousands of civilians.[1]

Since 2002, 775 men have been detained at Guantánamo Bay, though only eight have been convicted of any crimes, with four of those convictions reversed.

Some 37 prisoners currently remain incarcerated in Guantánamo under these conditions. President Joe Biden has not only kept the facility open but provided funding for its upgrade even though he promised to close it when he campaigned for the presidency.

In an interview with CovertAction Magazine, Philippe Diaz said “I didn’t invent anything in the movie. Everything is true. Of the 800 prisoners whose lives were ruined in Guantánamo Bay, 775 were innocent of any charges and there are still people being tortured there.”

Diaz continued: “Most people don’t know how bad things are at Guantánamo because the media for years gave the impression that the people sent there were the most dangerous terrorists and hence deserving of their fate. Donald Rumsfeld developed a huge machinery of propaganda to manipulate the media and public opinion. I Am Gitmo is designed to try to counteract that and awaken people to what has really gone on.”

A graduate of the University of Sorbonne in Paris with a degree in philosophy, Diaz is a co-founder of Cinema Libre Studio, which has been making socially conscious films for the last 21 years.

His previous film credits include a documentary on poverty narrated by Martin Sheen, on sex and politics, and on the civil war in Sierra Leone, which challenged dominant mainstream media narratives on the conflict by placing its origins in the Western drive for Africa’s natural resources.

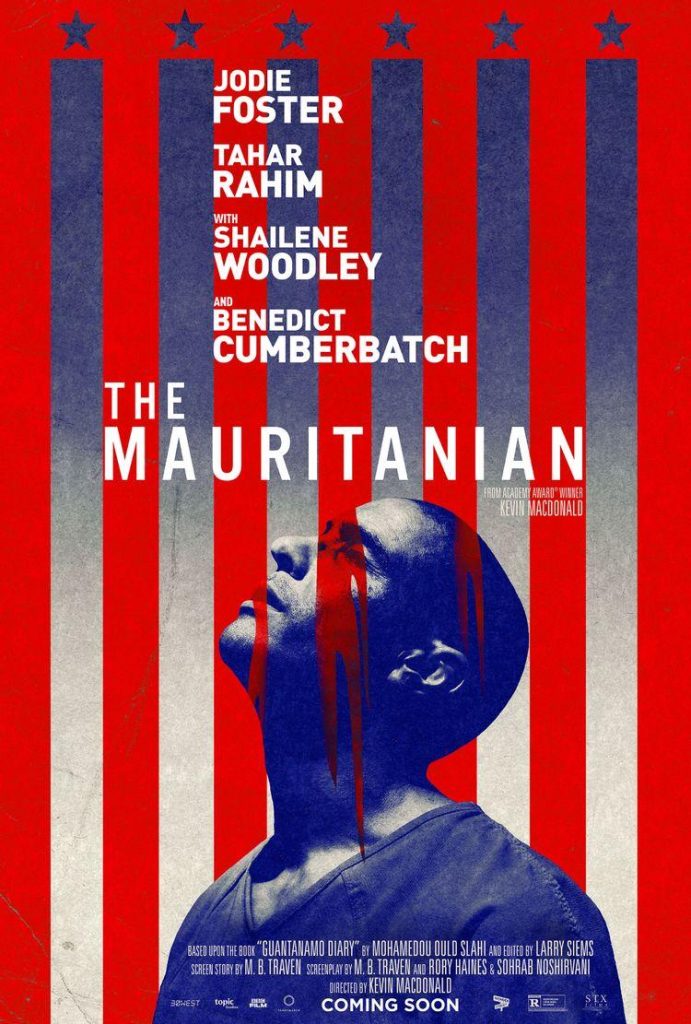

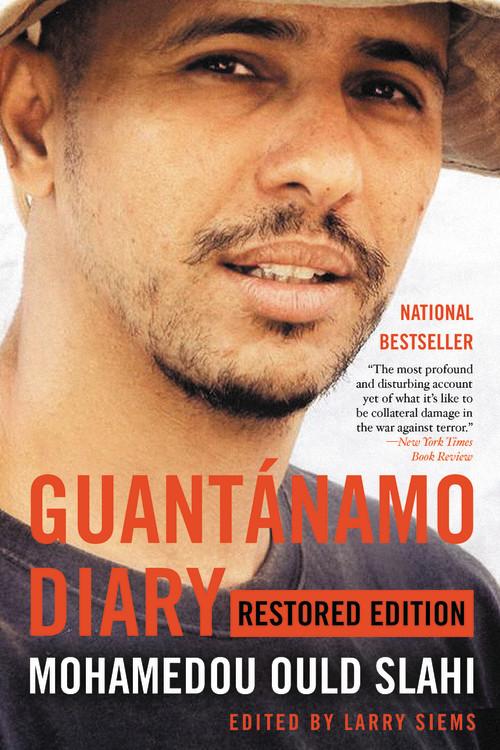

Diaz said that he was inspired to make I Am Gitmo after he read the book Guantánamo Diary by Mohamedou Ould Slahi, which was made into a feature film starring Jodi Foster called The Mauritanian. Diaz said that he almost fell from his chair reading the film’s script because it had only about two minutes depicting torture when Ould Slahi wrote about being tortured in vivid detail over nearly 300 pages.

Also in the film, Ould Slahi’s interrogator cracked jokes with him, and presented what Diaz called “the trope of the white hero” in which Foster, who plays his lawyer, saves the day by rescuing him from captivity. At the end, Ould Slahi is depicted making a lot of money off his book and living well, as if there is a happy ending to the story.

Diaz said that, in reality, most Guantánamo Bay inmates cannot go back to their own countries and are forced to go to “rehabilitation camps” in Saudi Arabia when they committed no crime.

While there are organizations out there calling for the closing of Guantánamo Bay, none is advocating for reparations for the victims of a torture regimen coming from the top of the U.S. government that has scarred victims.

Diaz says that he hopes I Am Gitmo will contribute to such a movement, which would entail the U.S. government being held accountable for the atrocities that it perpetrated.

In contrast to The Mauritanian, I Am Gitmo depicts Guantánamo Bay as the monstrosity that it is. The name of the film comes from a revolt where inmates refused guards’ orders to give their name during a cell count, proclaiming in unison, “I Am Gitmo.”

Diaz makes a point of presenting in graphic detail the torture that Sadek and other inmates experienced, including their being chained to the ceiling and floor, being sexually assaulted, subjected to mock executions, sleep and food deprivation, forced hooding, being buried underground and the water torture method designed to simulate drowning.

Diaz said that he wants the viewer to get a sense of what it was like for people to be tortured. In one memorable scene, the viewer is made to feel the coffin closing as Sadek is being buried.

The strength of Sadek’s character comes to light in a scene when he comes to the defense of an elderly inmate who was beaten by a sadistic guard because he was praying without authorization.

In this scene, Diaz provides commentary on the U.S. military’s contempt for Muslim culture, fanned by demagogic politicians and the media.

Diaz also shows how the U.S. government manufactured evidence against terrorist suspects in order to frame them.

Sadek’s chief interrogator, John Anderson (played by Eric Pierpoint), is given a photo purporting to show Sadek with Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan in the 1980s; however, the person said to be Sadek had his back facing the camera and cannot actually be identified.

Sadek’s Imam also allegedly confessed to Sadek’s membership in al-Qaeda, though we find out that the confession was induced through torture, and that the tape broadcasting it was garbled so it was not clear what the Imam actually said.

When Sadek is shown media accounts of his case, he is amazed to learn that he was a coordinator of al-Qaeda operations in Pakistan—which he never was.

Diaz suggests that this kind of biased media coverage helps solidify the public impression that Guantánamo Bay prisoners are the “worst of the worst”—as they were consistently called—and deserving of their fate.

I Am Gitmo is a superb film overall with great character development and dialogue. Some of the most stimulating scenes are ones depicting discussions between Sadek’s character and his lawyer (Bob Levin played by Paul Kampf) and chief interrogator, Anderson.

In those discussion, Sadek tells Anderson that Arabs had been victims of Western imperial machinations over centuries and that he was proud to join the mujahadin in the 1980s to fight against the Soviet Union, an atheistic power that had dishonored Muslims.

When Anderson accuses Sadek of being part of the 9/11 plot because he supposedly fought with Osama bin Laden, Sadek tells Anderson that he never knew bin Laden and that most Arabs believe that bin Laden had nothing to do with 9/11.

Rather they believe that al-Qaeda was a CIA creation and that the CIA and Israeli Mossad had planned 9/11 to provide a reason for the U.S. invading the entire Middle East.

Anderson responds to these comments with bafflement, saying that “Arabs and Americans live in two different worlds—how can they ever come together.” To which Sadek retorts: “When you believe everything your government tells you, they can’t.”

These latter comments are pointed in their suggestion that Americans must learn to think independently and should not trust what their government says.

Anderson is depicted in the film as a tortured soul who gives thought to some of the things Sadek and his daughter Cassidy, who is critical of U.S. foreign policy, tell him, but, ultimately, cannot accept them or believe that his government is in the wrong.

During a hearing in which Sadek’s lawyer is requesting a change in Sadek’s status from “enemy combatant” to Prisoner of War (POW)—which would make him subject to the Geneva Convention—Anderson testifies that he was not able to elicit any confessions or find any concrete proof that he was part of al-Qaeda or the 9/11 plot.

However, Anderson tells the judge that the U.S. government believes that Sadek is a terrorist and that he has no reason to doubt its credibility or judgment—sealing Sadek’s fate.

In an earlier interrogation session, Anderson had expressed his belief that U.S. government authority derived from God and was thus legitimate, even if some policies were hard to justify.

This is a subtle critique of organized religion and how it often promotes political conformity and conservatism—to the benefit of political elites.

After an army court denied Sadek’s change of status from enemy combatant to POW, Anderson calls his daughter, Cassidy, to tell her that the government had won a major victory in the War on Terror and that he was proud of his work in helping to keep her and people back in the U.S. safe.

Fittingly, however, Anderson can only leave his message on voice mail as Cassidy does not pick up the phone.

Earlier scenes reference Anderson’s estrangement from Cassidy because of his military career. She recommended that he watch Battleship Potemkin (1925), a pro-Bolshevik film by Sergei Eisenstein about a mutiny on a czarist ship. The insinuation was that Anderson should refuse military orders.

The tone in Anderson’s voice in the message he leaves Cassidy after Sadek’s hearing suggests that he recognized deep down that his daughter was correct: that there was no real victory when the army court ruled against Sadek and that he had given his life for a morally bankrupt cause—that of the American empire.

However, Anderson can never overtly acknowledge this, as he has given up too much of himself to his military career.

Anderson ultimately comes across as a weak man who lacks the moral fiber to admit his own mistakes and to escape the ideological conditioning to which he had been subjected.

At various moments, Anderson expresses misgivings about the sanctioning of torture methods by army authorities, but always falls back on the trope that these methods were given by presidential order, which he believes it is his duty to uphold.

Anderson has also convinced himself that sometimes bad things have to be done for the greater good—a logic adopted by perpetrators of state atrocities throughout history.

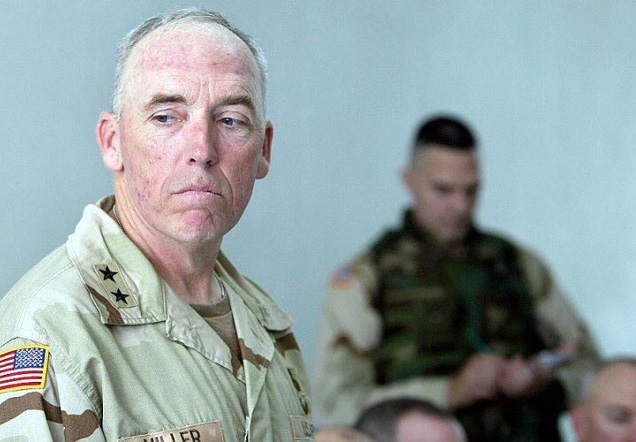

When a new commandant takes charge of Guantánamo Bay, modeled after General Geoffrey Miller, who later presided over the infamous atrocities at Abu Ghraib, Anderson acquiesces to his orders to brutalize the inmates—even when he recognizes that torture leads to false confessions and that the best interrogators obtain credible information by gaining the trust of captives.

The analogy of the “banality of evil”—which Hannah Arendt famously applied to Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann—seems to apply to Anderson.

He never himself tortures Sadek, helps to get him a decent meal, reprimands guards who mistreat him and other inmates, and adopts the more humane and progressive positions in internal army debates.

However, Anderson is still deeply complicit in major human rights crimes by playing the good cop in a good cop/bad cop routine, and is the one ultimately responsible for Sadek’s prolonged confinement at Guantánamo Bay.

Anderson considers himself to be guided by moral and religious conviction but therein lies his Achilles heel, as he cannot process views that challenge his own belief system—like Sadek’s or his daughter’s—and supports bad things when he believes it might be serving a higher cause.

This moral relativism contrasts with a Black prison guard, Officer Martin, played by Chico Brown, who tells Sadek while he was in the hole that he admires what he did in standing up for the elderly prisoner who was beaten.

Later, Officer Martin is shown at a bar drowning his sorrows with alcohol.

When Anderson reprimands him for drinking on duty, Officer Martin responds that “this is the only way I can forget about the horrific things going on here [Guantánamo Bay].”

Brown and Anderson’s characters are used to convey an important sub-theme of I Am Gitmo, namely that the casualties of a war such as the Global War on Terror include its foot soldiers.

Their service to the U.S. empire has rendered so many of them tortured souls who either drown out their internal guilt with alcohol or drugs, or become self-deluded human shells like Anderson, incapable of forging meaningful human relations even with members of their own families.

-

See Douglas Valentine, The Phoenix Program (New York: William Morrow, 1990). ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.

Excellent article about the system that brought men to Guantanamo and kept them there, even after the Bush and later administrations knew they were the wrong guys. If you’re in NYC, you can see this film starting this weekend at Cinema Village.