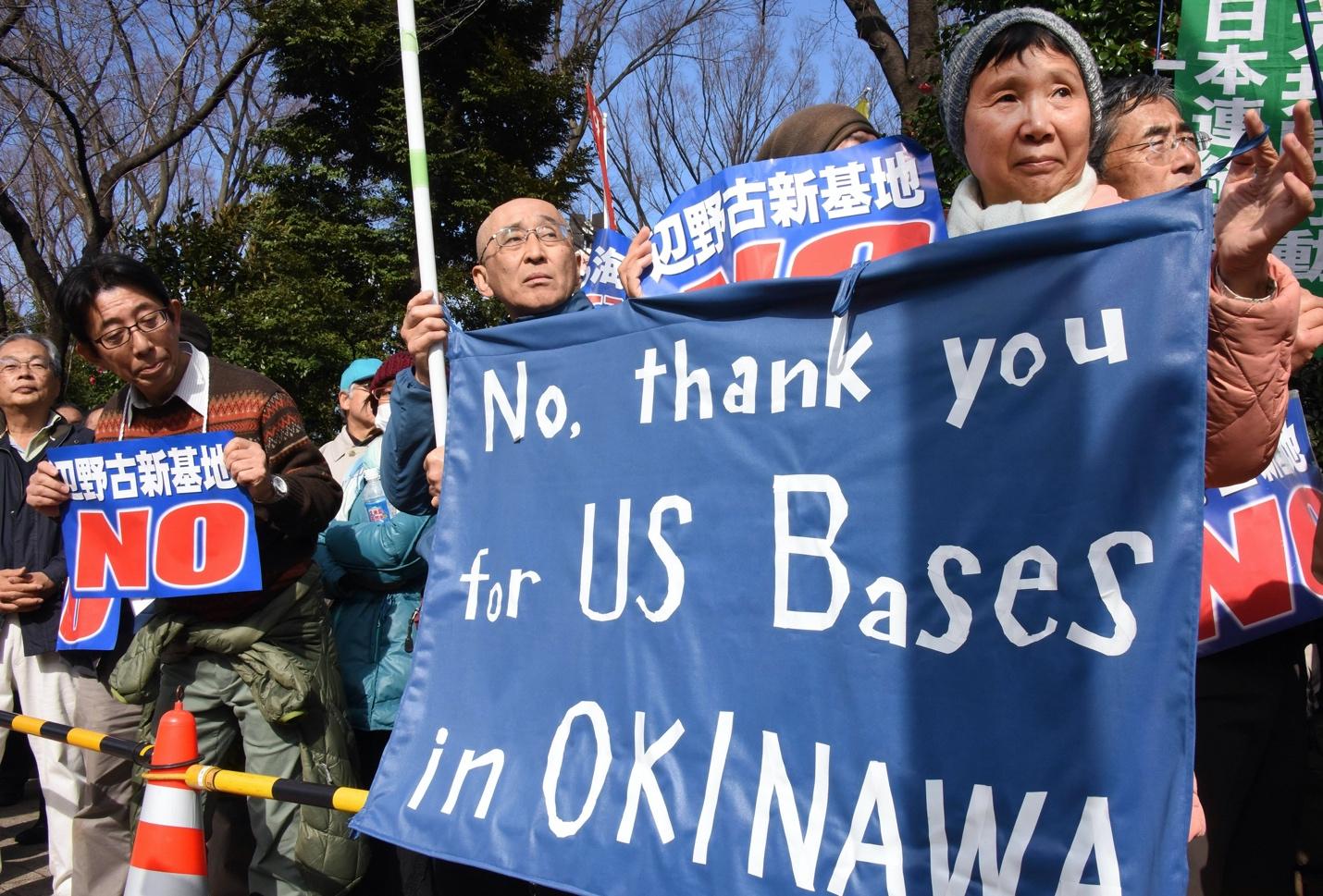

In late June, during public commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Okinawa—one of the bloodiest battles of the Pacific War that resulted in over 240,000 deaths—local authorities called for a reduction of the U.S. military presence in Okinawa, which hosts over 20,000 U.S. troops.

Last August, a protest near Marine Corps Air Station Futenma in Okinawa, which followed the conviction of two U.S. soldiers on sexual assault charges, attracted over 2,500 people.

Susumu Inamine, a former mayor of Nago city, told the crowd that the Japanese government had been hiding information regarding sexual assaults by U.S. troops and that even Okinawa’s governor was kept in the dark. Other speakers condemned the recent return of Bell Boeing MV-22 Osprey flights over the island, which are known for making a lot of noise.

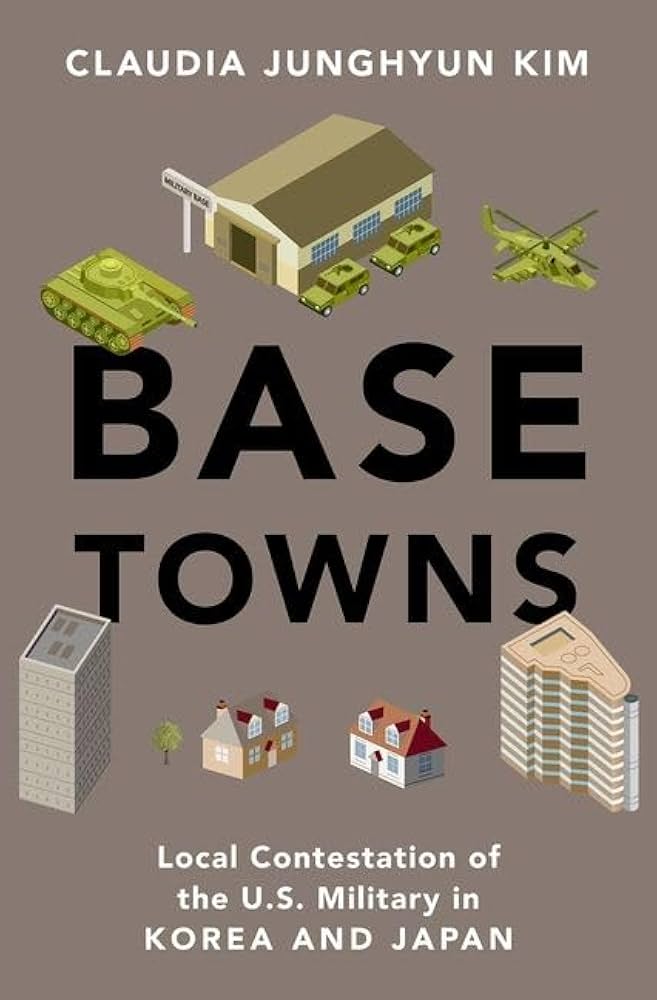

Claudia Junghuyn Kim, a professor of international affairs at City University of Hong Kong, is author of a new book called Base Towns: Local Contestation of the U.S. Military in Korea and Japan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023) that details a long pattern of protests directed against U.S. military bases in the Far East.

Kim carried out extensive research on the anti-base protest movement and participated in anti-base protests. One of the more inspiring ones occurred in 2014 near the South Korean city of Pocheon, outside the largest American firing range in Asia. Normally conservative farmers climbed up a mountain to act as voluntary human shields against shooting exercises and placed straw bales at locations surrounding the base and set them ablaze as they threatened to occupy the base, block its gate with farm tractors, and suspend water supplies.[1]

Kim observes that during the 1960s through the 1980s base protests were usually led by left-wing groups, including South Koreans demanding the removal of the bases as a precondition for the reunification of North and South Korea.

May 22 was designated as “Anti-American Day” because of U.S. support for the 1980 Kwangju massacre, where the South Korean dictatorship led by Roh Tae Woo massacred pro-democracy protesters. A popular protest song titled “Song For the USFK Withdrawal” proclaimed: “The Japs were expelled, and the Yankees came…we’ll wipe you out and march toward unification.”[2]

Japanese protesters portrayed the U.S. military presence as a betrayal of the spirit of Japan’s post World War II pacifist constitution and violation of its sovereignty.[3]

In Okinawa, a U.S. colony from 1952 to 1972 when it was returned to Japan, bases became a symbol of foreign imperial occupation and a trigger for pro-independence activists who were monitored by Okinawan police working under the U.S. Office of Public Safety, an agency headed by U.S. intelligence agents.[4]

The 1956 Price report published by the U.S. House Armed Services Committee codified an unjust system where Okinawan landowners were compensated only 6 percent of their land value by the U.S. military.[5] Historian Christopher Aldous wrote that this report helped spawn an “island wide struggle,” typified by mass rallies on June 20, 1956 when more than 160,000 Okinawans protested in 56 different demonstrations throughout the island.[6]

The boom in base construction during the Vietnam War resulted in further heightened protest known as the shimagurumi toso, or all-island struggle, which local police under the direction of the public safety division were called upon to surveil and try and control.[7]

In more recent years, Kim finds that most anti-base protests in South Korea and Japan have focused primarily on the negative environmental ramifications and problem of noise from U.S. live fire exercises or Air Force training. Other protests have focused on the sexual assaults of local women by U.S. soldiers.

Some of the protesters have sought to distance themselves from leftist groups because they feel they can gain more support from the wider community by focusing on local concerns rather than on geopolitics. They are weary of alienating themselves from local politicians and facing societal stigmatization in a political climate that is similar to the McCarthy-era in the U.S.

An annual South Korean poll between 2012 and 2019 showed support for the U.S. military presence ranging from 67 to 82 percent. Japanese polls also show acceptance of U.S. military bases, with some policy-makers alleging that the anti-base protesters are “on the Chinese payroll.”[8]

Kim writes that even setting aside the issue of the U.S. military, there is an aversion among the Japanese public for social movements, which some allege borders on phobia, making it difficult for the anti-base movement to expand.

Postwar security has been linked to the U.S. presence and growing military ambitions are synchronized with U.S. regional strategy.

In South Korea, the government legitimizes the existence of the U.S. bases by suggesting that the U.S. military helps to safeguard the country from the North Korean “threat.” Politicians remain “faithful to the American presence that they associate with security and prosperity,” Kim writes.[9]

When provincial or municipal government officials support the anti-base protesters, they often do so in order to gain financial concessions from Tokyo and Seoul. In this way, Kim suggests that local elite support for the anti-base movement can be a double-edged sword that results in the cooptation of the movement because the end goal is not actually the removal of the bases.

A major impediment to the growth of the base movement is the revenue that bases generate for local businesses and money that the federal governments in Korea and Japan will pump into communities that host bases in order to effectively buy off its people.

This is very similar to the situation in the U.S., where military bases are strategically placed in rural areas where they can provide an economic stimulus and local politicians end up lobbying against base closures because it would ruin the local economy.[10]

The U.S. acquired a vast array of military bases in South Korea and Japan as a spoil of the Pacific and Korean Wars. In South Korea, many of the bases were taken over from the Japanese colonizers.[11]

Today, the U.S. military has 83 military installations in South Korea and 121 installations in Japan, occupying hundreds of thousands of acres of fertile land mostly in Okinawa.[12]

The vast number of bases contradicts official histories in the U.S. taught to school children suggesting that the U.S. waged the Pacific and Korean Wars for altruistic and defensive purposes.

In reality, a key motive, laid out at the time by General Douglas MacArthur, was to establish a chain of military bases from the Ryukyu (Okinawa) to the Aleutian islands, from which the U.S. could take over from the European powers in dominating Southeast Asia while securing access to its rich mineral resources.

MacArthur told George F. Kennan in 1948 that Okinawans were a “simple and good natured people who would pick up a good deal of money and have a reasonably happy existence from an America base development in the Ryukyu.”[13]

Okinawans, however, protested the takeover of their land by the U.S. military in huge numbers and were met with significant repression, as was exemplified in the imprisonment in the 1950s of Kamejiro Senaga, Secretary General of the anti-imperialist Okinawa People’s Party (OPP), who was wounded during the violent suppression of a prison riot.[14]

In Japan, the Public Safety branch of the U.S. occupation authority mobilized Japanese police between 1945 and 1952 to suppress the Japanese Communist Party (JCP), which the OPP was a branch of.[15]

The CIA secretly financed Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which favored close integration with the U.S. during the Cold War along with a conservative economic program.[16]

In 1960, Japanese Prime Minister Kishi Nobosuke, the “Monster of Showa” who had overseen sadistic medical experiments on Chinese prisoners of war in World War II, signed a security deal with the U.S. that allowed the U.S. to retain its military bases in Japan indefinitely, paving the way for the situation today.[17]

The CIA infiltrated the militant public sector trade union, Sohyo, the main organizing arm of the Japanese Socialist Party, which was against the base deal.[18]

This history is relevant in helping to understand the relative political timidity of the anti-base movement today in Japan, which is a legacy of the Cold War and CIA’s collaboration with local elites in crushing Japan’s once vibrant anti-imperialist and socialist left.

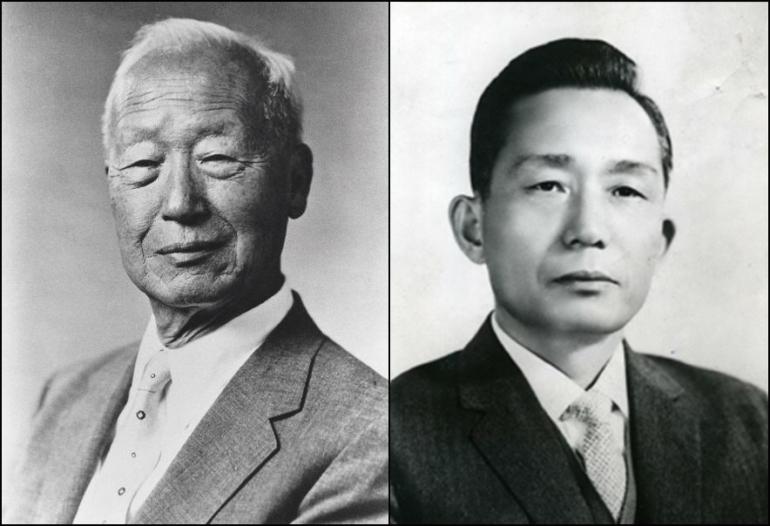

A similar pattern is at play in South Korea, where the CIA created the Korean CIA to empower right-wing leaders like Syngman Rhee (1945-1960) and Park Chung Hee (1960-1979), who supported a vast U.S. military presence in South Korea and accepted U.S. support in crushing the political left, which strove for Korean national reunification.

South Korea’s political landscape turned more to the right in 2014 after the disbanding of the Unified Progressive Party (UPP), which had functioned as a “bastion of leftist-nationalist politics.”[19]

Surviving elements of the anti-imperialist left in both South Korea and Japan have found common cause with right-wing nationalists who resent the emasculating effect of having a foreign military presence in their country.

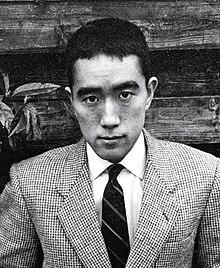

In Japan, a right-wing writer, Mishima Yukio committed suicide in 1970 after giving a speech suggesting that Japan’s Special Defense Force should become a “national military” and “break out of the U.S. hegemony.”[20] These comments make clear a wide unease with Japan’s function as an adjunct of U.S. power in Southeast Asia, across the political spectrum.

U.S. military bases are least popular in Okinawa, which was turned in the 1950s into “one continuous American base,” in the words of an American diplomat. Okinawa today houses 33 military installations on 46,229 acres of land, 70 percent of land used by the U.S. military throughout Japan.[21] Kim writes of an annual peace march in Okinawa and popularity of anti-base politicians like Inamine Susumu, Nago’s mayor from 2010 to 2018, and Otaga Takeshi.[22]

In 2010, President Barack Obama forced the resignation of Japanese Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio when he opposed an agreement that had been illegally rammed through the Japanese diet by his predecessor mandating the relocation of the Henoko air station in Okinawa.

According to historian Gavan McCormack, Hatoyama’s capitulation was considered a “day of humiliation for Okinawa akin to that of April 1952 when the islands were offered to the U.S. as part of a deal for the restoration of Japanese sovereignty [from U.S. military occupation].”[23]

These comments illustrate the injustice underlying the U.S. military base network that has resulted in continued protest over the decades.

That protest sadly has not extended very much to the U.S. itself because most Americans are oblivious as to the local consequences of U.S. military bases, which goes unreported in U.S. media. Peace activists are often concerned primarily with the latest military escalation rather than on trying to dismantle the structure of the American empire that enables the forever wars and human carnage associated with them.

Claudia Junghuyn Kim, Base Towns: Local Contestation of the U.S. Military in Korea and Japan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023), 1. ↑

Kim, Base Towns, 163. USFK stands for U.S. Forces Korea. In the 1980s, South Korean university students organized a movement to resist mandatory military training, stating they did not want to serve as “mercenaries for Yankees.” One student group was called “U.S. Imperialists’ Military Base-ification of the Korean Peninsula.” A 1986 protest song warned of a ‘nuclear storm” threatening “national survival” and cried out, “antiwar, anti-nuke, Yankee go home!.” ↑

The anti-base protests in Japan dated to the 1950s. See ie. Jennifer Miller, “Fractured Alliance: Anti-Base Protests and U.S.-Japanese Relations,” Diplomatic History, 38, 5 (2014). This article details a series of large-scale protests in the town of Sungawa bordering the Tachikawa Air Force base on the outskirts of Tokyo, in 1953-1954 which blocked the extension of a proposed runway. ↑

One of the directors, Harriman N. Simmons Jr. (1904-1985), was a Korean War veteran from New Jersey who had a background in military intelligence. Paul H. Skuse was a naval veteran who worked for the CIA in Indonesia and Laos where he helped recruit Vang Pao into the CIA’s clandestine army. ↑

Gavan McCormick and Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012), 78, 80. In 1953, U.S. forces requisitioned 63 percent of Iejima Island while bulldozing and burning the homes of 13 protesters. Ridiculously calling Okinawa a “showcase of democracy,” the Price report was named after Melvin Price, (D-Ill) who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1945 to 1988. In 1972, Okinawa reverted to Japanese control under a deal struck by the Nixon administration in which Japan agreed to allow for the maintenance of U.S. military bases in Okinawa. ↑

Christopher Aldous, “Achieving Reversion: Protest and Authority in Okinawa, 1952-1970,” Modern Asian Studies, 37, 2 (2003), 492. ↑

Kim, Base Towns, 40; McCormick and Norimatsu, Resistant Islands, 80. So vital was Okinawa for the waging of the Vietnam War that, in 1965, the Commander of U.S. Pacific Forces declared, “Without Okinawa, we couldn’t continue fighting the Vietnam war.” Jon Mitchell, “Vietnam: Okinawa’s Forgotten War,” The Asia Pacific Journal, April 20, 2015; During the 1971 Koza riots, Okinawans outraged over an incident where a U.S. military vehicle overran an Okinawan civilian, destroyed more than 80 U.S. military and private vehicles before they were subdued by Okinawan police and the U.S. which sprayed tear gas into the crowds. ↑

Kim, Base Towns, 45. Anti-base protesters in Okinawa are maligned for allegedly helping to carry out a scheme to boost Chinese influence, in part because the administration over the disputed Senkaku and Diayou islands lies with the Okinawa city of Ishigaki. ↑

Kim, Base Towns, 45. ↑

See Joan Roelefs book, The Trillion Dollar Silencer: Why is There So Little Anti-War Protest in the United States (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2023). ↑

Kim, Base Towns, 15. Many in the Global South have long viewed South Korea as an American client state or puppet because it was occupied by tens of thousands of U.S. troops along with advisers operating under civilian cover who trained the South Korean police and intelligence services.Tycho Van Der Hoog, Comrades Beyond the Cold War: North Korea and the Liberation of Southern Africa (London: Hurst & Co., 2025), 58. ↑

Kim, Base Towns, 13. ↑

MacArthur quoted in Christopher Aldous, “Achieving Reversion: Protest and Authority in Okinawa, 1952-1970,” Modern Asian Studies, 37, 2 (2003), 486. ↑

“7 Convicts Shot in Okinawa Prison Riot,” Okinawa Morning Star, December 29, 1954, obtained by the author in the private files of Paul H. Skuse, a police adviser in Okinawa, whose grand-daughter, Kimberley Macgregor, lives in Los Angeles. ↑

See Jeremy Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression: Police Training and Nation Building in the American Century (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), ch. 3. ↑

Michael Schaller, America’s Favorite War Criminal: Kishi Nobusuke and the Transformation of U.S.-Japan Relations (Japanese Policy Research Institute, July 1995). The secret funds were allegedly obtained from the sale of rare metals and diamonds that had come under allied control at the end of World War II and looted gold seized under the oversight of Air Force General Edward Lansdale, an Office of Strategic Services (OSS) propagandist and legendary CIA operative. ↑

Schaller, America’s Favorite War Criminal. ↑

Brad Williams, “US Covert Action in Cold War Japan: The Politics of Cultivating Conservative Elites and Its Consequences,” Journal of Contemporary Asia, 50, 4 2020, 593-617. ↑

Kim, Base Towns, 44. ↑

Kim, Base Towns, 39. ↑

Kim, Base Towns, 17, 33. ↑

Kim, Base Towns, 133. ↑

Jeremy Kuzmarov, Obama’s Unending Wars: Fronting the Foreign Policy of the Permanent Warfare State (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2019), 209, 210. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.