[This article is one of two published by CovertAction Magazine on George Orwell that offer two divergent interpretations about Orwell’s career and legacy. Here is the first, a movie review of Orwell: 2+2=5 that just debuted.—Editors]

Rather than being some kind of prophet, Orwell was a literary Cold Warrior who plagiarized works and critiqued the Soviet Union more than he did Nazi Germany

The current state of ever-expanding government surveillance and endless war elicits frequent comparisons to George Orwell’s dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

The conventional biography portrays Orwell as an honest and original writer, a veritable prophet of the digital age, but there is another side to him which is omitted from the mainstream narrative. The cultural impact of his work is unavoidably felt in that many terms invented by him have wormed their way into the popular lexicon, perpetuating the image of his ingenuity.

Orwell’s neologisms, such as “Big Brother,” “doublethink,” “Thought Police,” and “memory hole” retain common usage to this day. The English author’s name has even become eponymous with the word “Orwellian,” which is often employed to indicate “totalitarian” policies. (The New York Times noted that the term has been “the most widely used adjective derived from the name of a modern writer.”)

“Orwellian” has been used to describe various countries and forms of government, demonstrating how Nineteen Eighty-Four and its author span the political spectrum.

However, Orwell’s own politics remain a subject of debate. To many on the right, he was a principled cold warrior, defending freedom against the Evil Empire and the encroachment of “big government” while, to many on the left, Orwell was a committed socialist who upheld the ideals of socialism against the “betrayal” of the Soviet Union under Stalin.

Orwell’s left-wing devotees will often excuse his appeal to reactionaries by referring to his “turn to the right” at the end of his life. Yet political one-eighties do not usually occur unless there was some basis for such a shift to begin with.

The English novelist’s personal life demonstrates his implicit support for the British empire, even though he criticized it in word, as well as an acute hostility toward actually existing socialism.

Orwell’s view that Western capitalism and Eastern socialism were equally bad can be seen to have ultimately amounted to capitulation to the West, which is often the case with those who attempt to transcend realpolitik for the supposedly higher realm of ideals. The origins of his non-antagonistic relationship to the British government likely emanates from his family history.

Eric Arthur Blair, later to adopt the pseudonym George Orwell, was born in British-occupied India in 1903. The Blair family had long been involved in British colonialism: Orwell’s great-grandfather, Charles Blair, was a slave-owner and landlord of two Jamaican plantations and his grandfather, Thomas Richard Arthur Blair, served in a British Army infantry regiment which fought against the Xhosa people at the Cape of Good Hope.

Richard Walmesley Blair, his father, oversaw the production and storage of opium for sale to China and worked as a sub-deputy Opium Agent in the Opium Department of the Indian Civil Service. Both of Orwell’s uncles had been similarly interwoven into the colonial government—Horatio Douglas Blair, like his brother Richard, worked in the Opium Department and Arthur Richard Blair was a District Superintendent of Police in Bengal.

Orwell’s uncle on his mother’s side, George Limouzin, was also a member of the Indian Imperial Police and likely his inspiration for the first half of his assumed name. As a one-year-old, Orwell’s mother took him and one of his two sisters back to England and, although he did not spend much time in India with his father, his familial connection to British-occupied India would come to play a defining role in his life and worldview. Steven Runciman, who had attended Eton College with Orwell, noticed how he had a “romantic idea” about the East and was not surprised to learn that he followed in the footsteps of the Blair family patriarchy.

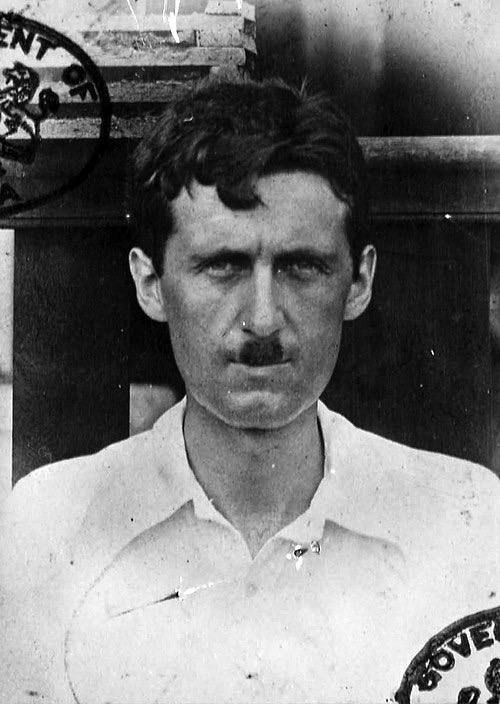

In October 1922, Orwell sailed to Burma to join the Indian Imperial Police. During his time as an officer, he was responsible for the security of approximately 200,000 people. Yet security was a euphemism for colonial rule, and Orwell recalled that he faced hostility from the Burmese in his essay “Shooting an Elephant.” Writing of his time as an officer in the Indian Imperial Police force, he recalled that “I was stuck between my hatred of the empire I served and my rage against the evil spirited little beasts who tried to make my job impossible.”

Perhaps Orwell’s later unwillingness to join the Popular Front in Spain and his apathetic attitude toward Nazi Germany was related to his time working on the side of British colonialism. As Frantz Fanon and others have noted, historically the colonial countries are the incubators of fascism which subsequently migrates back to the imperial core, i.e., the proverbial colonial chickens coming home to roost.

Orwell himself acknowledged the repressive effects of colonialism, even among the oppressors, when he noted the lack of freedom of speech possessed by the British officers stationed in India. Throughout his life, his conscience was seemingly bothered by what he had done during his stint as an imperial enforcer, yet Orwell retained the habit of viewing the “Orientals” in a patronizing and, quite frankly, racist fashion.

The residual guilt from actively being on the side of the oppressors led Orwell to trip over his own feet to side with the oppressed during the Spanish Civil War, and by his own admission he began to valorize the down-trodden. Yet consistent with his time as a colonial disciplinarian, he always retained a patronizing and condescending attitude toward the exploited, something which came out strongly in his fictional writing.

After Francisco Franco’s military coup in Spain, Orwell purportedly felt morally obligated to take up arms and fight in the Spanish Civil War on behalf of the Republic. Under the impression that one needed papers from a left-wing organization to cross the frontier, Orwell applied to join the International Brigades, which were the soldiers recruited and organized by the Communist International (Comintern).

However, Harry Pollitt, the leader of the Communist Party of Great Britain, was skeptical of Orwell’s political reliability and turned down his request. Orwell ended up never joining the Brigades, most likely because of his antipathy toward the Soviet Union and Stalin. Eventually, his tenuous relationship with the Communist movement deteriorated.

In his 2005 biography of Orwell, Gordon Bowker wrote, “Although he did not think much of the Communists, Orwell was still ready to treat them as friends and allies. That would soon change.” Change it certainly did, and Orwell was subsequently rebuffed by the Communist press for being a fascist. To become a fighter in the Spanish Civil War, Orwell ended up using his connections in the Independent Labour Party (ILP). The ILP was linked to the Spanish Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), in which Orwell enlisted upon his arrival in Barcelona.

POUM was profoundly influenced by Leon Trotsky and his views of the USSR after his expulsion, as well as his theory of “permanent revolution.” However, Trotsky himself did not endorse the party because of POUM’s fusion with the Right Opposition and went so far as to pen an essay entitled The Treachery of the Spanish “Labour Party of Marxist Unity.”

In 1938, after he penned Homage to Catalonia, Orwell wrote to Frank Jellinek (who was a correspondent with the Manchester Guardian in the Republican-controlled part of Spain during the Civil War and subsequently wrote a book on the subject) that “I’ve given a more sympathetic picture of the POUM line than I actually felt, because I always told them that they were wrong and refused to join the party.”

Surprisingly, there is even a passage in the book itself where Orwell admits that the Communist war policy was more practical and their propaganda more convincing than that of POUM’s, acknowledging in hindsight that their strategy was the only one capable of winning the war. After all, POUM’s membership never numbered more than 30,000.

Yet his famous book succeeds in portraying the USSR as the country which betrayed the Spanish Republic. The blind eye Britain, France, and the United States turned to Spain’s plight is omitted. In Orwell’s view, the Spanish Civil War revealed the counter-revolutionary nature of the Soviet Union and most of his book is spent demonizing the Communists while only a page or so actually discussed the Francoist movement.

However, history has shown that by prioritizing their own revolution over winning the war against fascism, Trotskyists and anarchists objectively helped to facilitate Franco’s military success. (The great academic Michael Parenti has written about this repressed aspect of history in his book Blackshirts and Reds:Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of Communism.)

It should be noted that Orwell’s account of the Spanish Civil War, Homage to Catalonia, informs much of the Anglophone world’s view of the conflict, a work which, not coincidentally, helped to tarnish the reputation of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) and the Soviet role in the conflict.

Herbert Matthews, a New York Times correspondent who was sent to Spain in 1937, noted that, “This book did more to blacken the loyalist cause than any work written by enemies of the Second Republic.” The journalist and war correspondent Alaric Jacob, who had been to Moscow (Orwell himself never visited the USSR) and later featured on Orwell’s list (mentioned later in this article), was disturbed by the account he gave of the conflict.

In an essay, Jacob wrote that, had he been in contact with Orwell at the time of Homage to Catalonia’s publication, he would have argued against it in this way:

“You used your experience in Spain in an entirely subjective way, without thought for the wider issues. It was wildly romantic of you to suppose that the 30,000 men of POUM could ever have produced a Marxist revolution in Spain while fighting Franco at the same time. They would have produced an isolated Trotskyite republic that would soon have been overthrown. The Western Powers would have seen to that—even if it meant siding with Hitler and Mussolini to do it. Set up a Communist regime in Spain and you justify Franco’s case up to the hilt and invite the rest of Europe to join his glorious anti-Bolshevik crusade! You say the Soviet Union has betrayed the Spanish working class by calling for a Popular Front rather than a Communist state. I say that in this particular the Soviet Union is entirely right. Even if Franco is defeated it will only be one battle in a much bigger war. How do you think we can ever deal with Hitler without a Popular Front to confront him with the danger of war on two fronts—Britain and France on the one side and the Red Army on the other.”

In May 1937, Orwell was wounded at the front by a bullet in the neck and was sent to a POUM-run sanatorium. However, aside from this incident, his division was regularly far from the front lines. Orwell admitted to having seen little fighting and even had the gall to write that “Nobody bothered about the enemy.”

By the middle of June, POUM was outlawed in Barcelona and, on July 13, a deposition was presented to the Tribunal for Espionage and High Treason in Valencia, which charged Orwell and his wife with rabid Trotskyism by citing the couple’s collaboration with the organization. The mainstream account is that POUM was persecuted by the backwards and power-hungry “Stalinists,” yet it must be remembered that the organization, along with the anarchists, had been disruptive of the war effort and served to undermine the Popular Front, paving the way for fascist forces.

Orwell admitted this, albeit rather circuitously, in his 1942 essay Looking Back on the Spanish War, when he wrote: “The Trotskyist thesis that the war could have been won if the revolution had not been sabotaged was probably false. To nationalize factories, demolish churches, and issue revolutionary manifestos would not have made the armies more efficient. The fascists won because they were stronger, they had modern arms and others hadn’t.”

Indeed, the fascists were for the most part more organized and unified than the Republican side, the unification of which groups like POUM actively sabotaged by rejecting the Popular Front, which they viewed as “class collaboration.”

Ironically, Trotsky viewed POUM’s fusion with the Right Opposition as “class collaboration.” Orwell conveniently forgot to mention that the Republican side was not entirely without proper weapons, as they had armed support from the Soviet Union and Mexico.

Incidentally, Western liberal democracies, such as France, the UK, and the U.S., refused to send arms, purposefully ignoring the rise of fascism. Taking into account an essay published in New English weekly, the branding of Orwell as a fascist by the Communist press does not seem entirely unjustified.

Printed on March 21, 1940, Orwell gave a review of Hitler’s Mein Kampf in which he wrote:

“Hitler could not have succeeded against his many rivals if it had not been for the attraction of his own personality, which one can feel even in the clumsy writing of ‘Mein Kampf’, and which is no doubt overwhelming when one hears his speeches. I should like to put it on record that I have never been able to dislike Hitler. Ever since he came to power—til then, like nearly everyone, I had been deceived into thinking that he did not matter—I have reflected that I would certainly kill him if I could get within reach of him, but that I feel no personal animosity. The fact is that there is something deeply appealing about him. One feels it again when one sees his photographs—and I recommend especially the photograph at the beginning of Hurst and Blackett’s edition, which shows Hitler in his early Brownshirt days. It is a pathetic, dog-like face, the face of a man suffering under intolerable wrongs. In a rather more manly way it reproduces the expression of innumerable pictures of Christ crucified, and there is little doubt that that is how Hitler sees himself. The initial, personal cause of his grievance against the universe can only be guessed at; but at any rate the grievance is here. He is the martyr, the victim, Prometheus chained to the rock, the self-sacrificing hero who fights single-handed against impossible odds. If he were killing a mouse he would know how to make it seem like a dragon. One feels, as with Napoleon, that he is fighting against destiny, that he can’t win, and yet he somehow deserves to. The attraction of such a pose is of course enormous; half the films that one sees turn upon some such theme.”

Perhaps Orwell had a certain affinity for Hitler because he used to sport the same toothbrush mustache during his stint with the Imperial Police. Jokes aside, it is disturbing to recall that Orwell wrote this review at a time when Nazi Germany was sterilizing the mentally ill, murdering the elderly, and shipping the Jews and Romani off to the concentration camps. Three years later he continued to demonstrate his view that Soviet communism was a greater threat to the Western civilization than Nazism.

In 1943, at a time when the West had finally partnered with the USSR in order to combat the fascist threat, Orwell claimed that the ultimate test of intellectual honesty was a willingness to criticize Stalin and Soviet Russia. This statement is rather vacuous for someone writing from the comfort of England where one was not subject to repression for criticizing Stalin.

If only Orwell could have lived to see the anti-Stalinist fervor that gripped the West after Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech.” As with many anti-Soviets, Orwell ended up painting Stalin in a much darker light than Hitler. “One could not have a better example of the moral and emotional shallowness of our time, than the fact that we are now all more or less pro Stalin. This disgusting murderer is temporarily on our side, and so the purges, etc., are suddenly forgotten,” he wrote in a diary entry from 1941.

In Orwell’s mind, Hitler was a man who suffered “intolerable wrongs” while Stalin was an abhorrent butcher. This is a historical obfuscation of considerable magnitude, not to mention an implicit absolution of the crimes that were committed by his own country’s “disgusting murderer,” namely the imperialist Winston Churchill.

Consistent with his intense antipathy toward Stalin, Orwell initially opposed war with Nazi Germany if it meant forming an alliance with the Soviet Union. Only when the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed in 1939 did Orwell suddenly support war against fascist Germany.

The highly strategic non-aggression agreement proposed by the Nazis was accepted by the Soviet leadership in order to buy time before the imminent war and only after being repeatedly rebuffed by the West at forming an anti-fascist alliance.

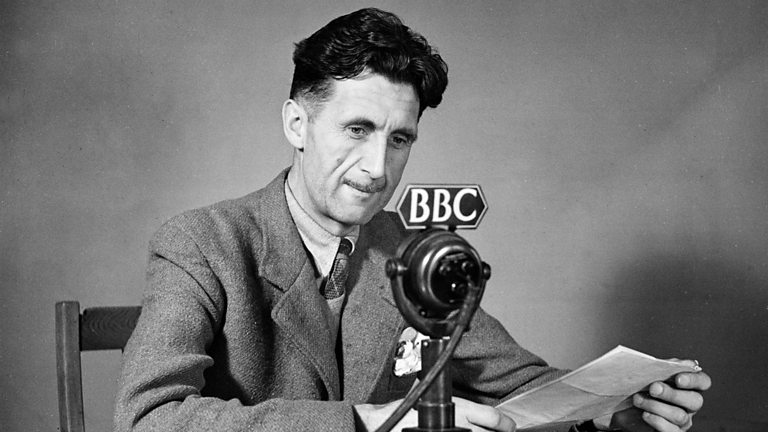

At the beginning of World War Two, Orwell’s wife began working at the Censorship Department of the Ministry of Information in London, but Orwell did not manage to obtain “war work” until August. He was taken on full time by the BBC’s Eastern Service, where he supervised cultural broadcasts to India which were aimed to engender support for the British war effort amongst the colonial population. Ironically, the man viewed as the great critic of propaganda wrote about becoming propaganda-minded and made a cunning spin doctor himself during his time at the BBC’s India Section.

In his diary he wrote, “All propaganda is lies, even when one is telling the truth. I don’t think this matters so long as one knows what one is doing, and why…” It is very probable that Orwell was able to be such an incisive satirist of propaganda because of his own stint as a propagandist.

However, in typically “Orwellian” fashion, he himself was subject to British government surveillance. Orwell came under the eye of Special Branch and MI5 in early 1936, at which time he was investigating the living conditions of the working class in Lancashire and Yorkshire for his book The Road to Wigan Pier. (A controversy arose after a review by Harry Pollitt in The Daily Worker, the Communist Party of Great Britain’s newspaper, in which he attacked Orwell for a passage stating that he had been raised to believe “the lower classes smell” growing up in a middle-class environment. Orwell threatened to take libel action against the paper, but never followed through.)

What originally called Orwell to the attention of the British government was that he had attended a Communist Party meeting, which marked him as a potential subversive. In January 1942, Sergeant Ewing of the Special Branch monitored Orwell’s attempts to recruit Indians to work for the BBC’s India Service because he suspected him of having “communist views.” In the end, the Special Branch, after monitoring Orwell for more than a decade, decided he was not an orthodox communist.

The Special Branch’s monitoring of Orwell was more evidence of the anti-communist fervor of the time than proof of his political radicalism. Ultimately, the British government did not consider him to be a threat. In fact, he would go on to do work for the state, ratting out subversives. In 1949, the supposed prophet of government surveillance offered to provide information to the covert branch of the British Foreign Office, the Information Research Department (IRD). The IRD was dedicated to disinformation warfare, anti-communism, and pro-colonial propaganda and played an active role in dividing the international labor movement.

It also weaponized prominent writers and publishers for propaganda purposes during the Cold War. In March of that year, an IRD official visited an ill Orwell at a sanatorium. Celia Kirwan, the official who visited the ailing author, was an assistant to the anti-communist historian Robert Conquest at the IRD as well as the sister-in-law of another IRD anti-communist, Arthur Koestler.

Kirwan, during her talk with Orwell, discussed the work that the IRD was doing, for which he expressed his enthusiastic approval. The “Solzhenitsyn without a Gulag,” as he has been described, offered to provide the IRD with a list of authors, artists and musicians that he regarded as untrustworthy, i.e., those harboring communist sympathies.

The Secret Service’s unwillingness to fully disclose Orwell’s lists shows the importance of the matter, making them more than a post-war trifle.

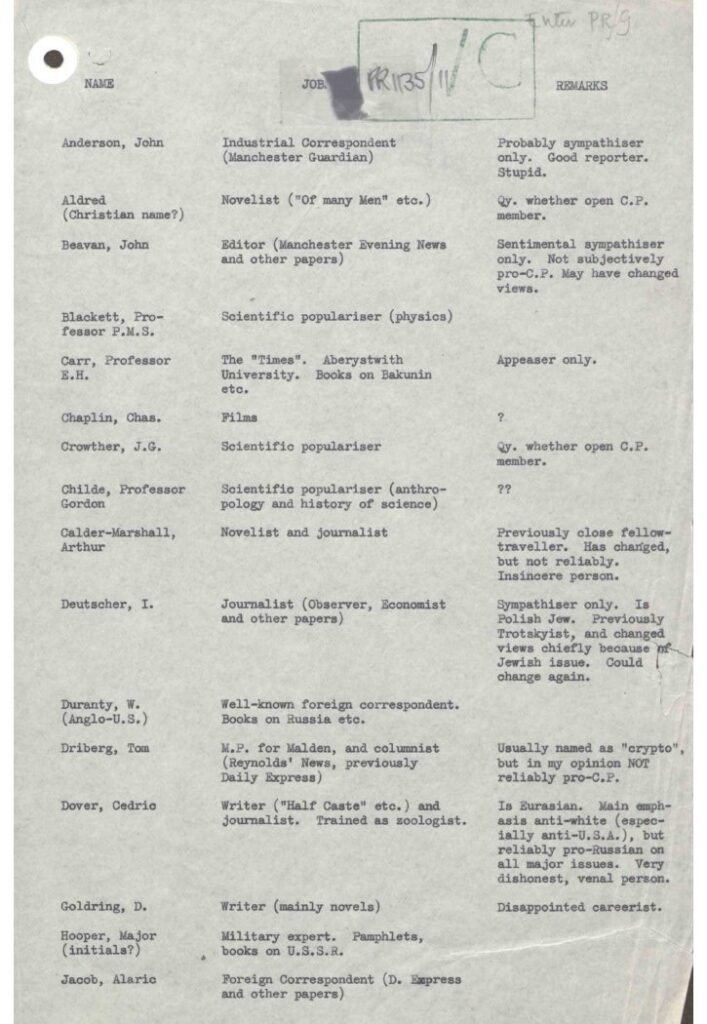

In a letter to Celia Kirwan, Orwell wrote that “I could also, if it is of any value, give you a list of journalists and writers who in my opinion are crypto-communist, fellow-travelers, or inclined in that way and should not be trusted as propagandists.

This is the second time Orwell tacitly admits to being a propagandist in his correspondence.

In the above-mentioned letter Orwell also noted how he thought that “anti-anti-Semitic” material should not be used in propaganda against the USSR. He viewed the Soviet Union as anti-Semitic because of its opposition to Zionism and he thought that the prevalence of Jews within the communist movement made it difficult to use accusations of anti-Semitism as effective propaganda.

Yet Orwell himself seemed to harbor prejudice against Jews, as his infamous lists reveal. The typed list he sent to the IRD, 38 names in total, was only a fraction of those he had under his watch. (He kept a notebook containing 135 names of people that he suspected were communists.)

Alongside the names were the occupations of the suspects, as well as a third column for “remarks.” A few notables who caught his attention were legendary filmmaker Charlie Chaplin and singer/actor Paul Robeson, the latter of whom he characterized as “very anti-white.”

The qualities that garnered Orwell’s suspicion were Jewishness, Blackness, and homosexuality, leading the journalist Alexander Cockburn to comment that the lists revealed him to be a bigot.

One might say it revealed his hypocrisy as much as his bigotry, given that most of his writing criticized government surveillance, yet he was completely comfortable working as an informant. (Incidentally, Cockburn’s father, journalist Claude Cockburn, himself had come under Orwell’s fire: He featured in Homage to Catalonia as the “Stalinist” journalist under the pseudonym Frank Pitcairn.)

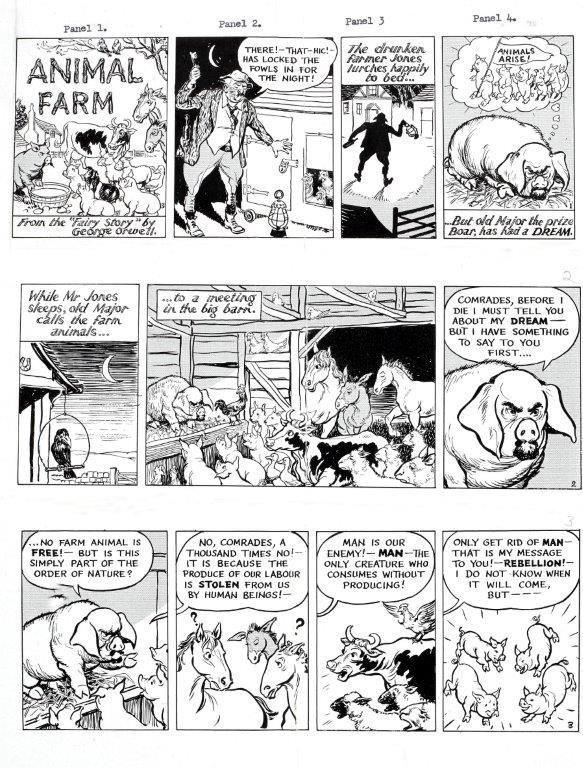

Another connection between Orwell and the IRD was with his famous novella Animal Farm. The IRD promoted foreign language editions of the text, translating it into more than 16 languages. The British Embassy promoted it in 14 different countries, particularly in the Middle East with the aim of propagandizing the Muslim world at a time when socialist and pan-Arabist movements were emerging in the region. An embassy official in Cairo noted its effectiveness as propaganda, stating that “The idea is particularly good for Arabic in view of the fact that both pigs and dogs are unclean animals to Muslims.” However, the IRD was not the only governmental organization interested in using Animal Farm for propaganda purposes.

Between 1952 and 1957, a CIA operation located in West Germany (codenamed AEDINOSAUR) launched millions of large balloons bearing copies of Orwell’s book over Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

While searching for a publisher for his manuscript of Animal Farm, Orwell was warned by both T. S. Eliot, then an editor at Faber & Faber, and William Empson, a war-time acquaintance from the BBC, that the text was ambiguous and could be interpreted in various ways.

One publisher, interpreting Orwell’s writing in much the same way as the CIA, declined the book because of its overt anti-Sovietism and the offensive depiction of the Bolsheviks as pigs. At a time when Nazi Germany was waging war on Europe, Orwell was more concerned with painting Britain’s wartime anti-fascist ally in the blackest possible light.

Coincidentally, Animal Farm was first published the month of Nazi Germany’s surrender, just as the West began to shift its resources back to fighting its real enemies: the Soviet Union and the spread of communism.

Demonstrating the ambiguity of Orwell’s text and the vagaries of the Cold War era, at the time the Soviet media claimed that Animal Farm was depicting the United States. However, the FBI assessed the novel to determine whether it was a satire of American society and concluded that it was directed against the USSR. The latter interpretation is the one that has won out in history.

The FBI’s reading of Animal Farm seems to align with the author’s intentions. Orwell confided in his friend George Woodcock that “Trotsky-Snowball was potentially as big a villain as Stalin-Napoleon, although he was Napoleon’s victim.” It is apparent from this statement that he thought that the Soviet project would have gone just as “badly” had it been under the leadership of Trotsky. Animal Farm, viewed in this light, is a condemnation of revolutions altogether; they are hopeless endeavors which only result in a new dictatorship.

Yet the novella satirized not only the Russian Revolution, but also the Stalin-Trotsky conflict, a feud which also was portrayed in Nineteen Eighty-Four. In the dystopian novel the face of the “totalitarian” government, Big Brother, is described in a way that resembles Stalin and his iconic mustache. Big Brother’s political rival, Emmanuel Goldstein, is surely given a Jewish moniker as a nod to Trotsky’s given name of Lev Bronstein. Both of Orwell’s novels attempt to make a mockery of the first socialist project in history, something which should not be an aim of any legitimate leftist.

There is good reason that his books became an integral part of the anti-communist canon: They were inherently anti-Soviet. Posev, an anti-communist publishing house backed by emigré White Russians, translated Orwell’s books. As a rule, they did not publish Russian editions of foreign texts, Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm being the sole exceptions.

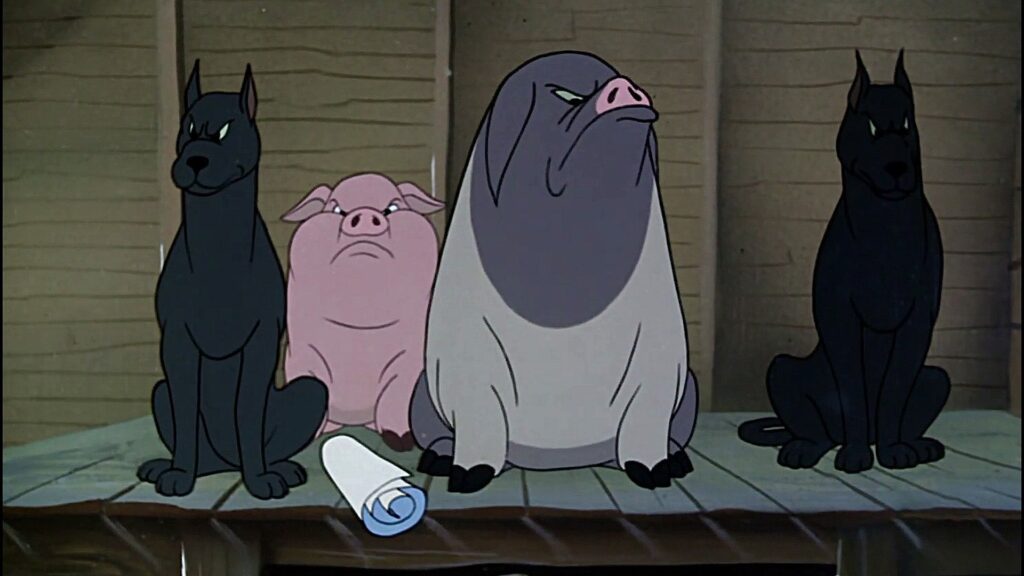

Orwell’s publisher since 1938, Fredric Warburg, also worked for the IRD. (Interestingly, Warburg became a member of the Society for Cultural Freedom which produced the CIA-funded magazine Encounter.) Along with Orwell’s widow, Warburg was involved in the allegedly unwitting sale of the rights of Animal Farm to CIA officers. This was part of the arrangement for the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), the espionage and counter-intelligence arm of the CIA, to produce a film version of Animal Farm.

Frank Wisner, the director of the OPC, was told by his superiors to build an organization focused on “propaganda, economic warfare; preventative direct action, including sabotage, anti-sabotage, demolition and evacuation measures; subversive against hostile states, including assistance to underground resistance groups, and support of indigenous anti-communist elements in threatened countries of the free world.”

As is evident, the OPC was intently focused on propaganda and enlisted the anti-communist documentary maker Louis de Rochemont to produce the adaptation. The agency opted to get the film made in Britain so as to obfuscate CIA involvement in the project, with most of the funding coming from Touchstone, a CIA shell corporation.

E. Howard Hunt, the infamous CIA operative best known for his role and conviction in the Watergate scandal, spearheaded the initiative to adapt Animal Farm for propaganda purposes.

His job was to remove elements that could be construed as anti-capitalist or anti-American from Orwell’s allegory because the CIA had determined that the end of the book needed to be altered in order to make the film more explicitly anti-communist. The cartoon ends with the rest of the animals overthrowing the pigs in a second “revolution,” whereas, in Orwell’s original work, the domination of pigs lasts for all eternity, presumably because the other animals are not competent enough to get themselves out of their predicament.

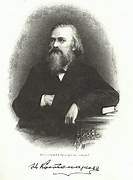

Aside from the way in which Orwell’s work was used, he seems to have a habit of taking advantage of little-known Slavic writers. It has been speculated by John Reed, the author of Snowball’s Chance (a parody and unofficial sequel to Orwell’s allegorical satire), and other writers that Animal Farm borrowed heavily from the story Animal Riot by Nikolai Kostomarov.

When one compares paragraphs from the two texts side by side, as Reed did in The Never End: The Other Orwell, the Cold War, the CIA, MI6, and the Origin of Animal Farm, the resemblance is staggering. Animal Riot also predated Animal Farm by decades. Originally written in 1879, Kostomarov’s text was republished after the Russian Revolution in 1917. It is very possible Orwell was familiar with Kostomarov and borrowed from his work. After all, he had similar views about history and he was one of the most distinguished Russian-Ukrainian historians.

Kostomarov was also a poet, ethnographer, pan-Slavist and supporter of the Narodnik movement, which was the historical 19th century precursor to the Socialist Revolutionary Party, a rival faction to the Bolsheviks. It is highly likely that Orwell, given the circles that he ran in, was acquainted with Animal Riot and Kostomarov’s work.

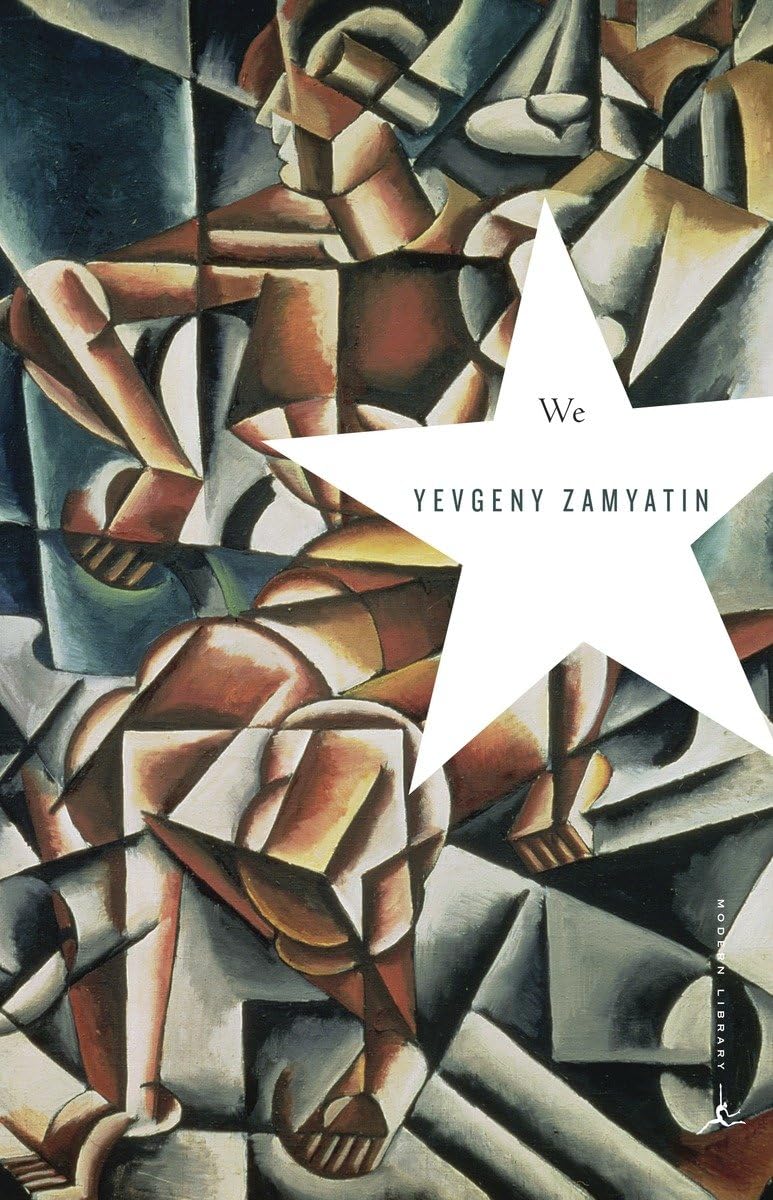

The originality of Nineteen Eighty-Four is also highly doubtful, although in its case it is verifiable that Orwell knew the material he was plagiarizing. The work in question was the short novel We by Yevgeny Zamyatin, a Russian author who was nicknamed “the Englishman” by his friends because of the years he spent in England and for his Westernized style of dress. As an editor and translator, Zamyatin spent much of his time dealing with the works of Western authors, translating writers such as Jack London, Jules Verne, and H. G. Wells into Russian.

Zamyatin was also known for being one of the earliest Soviet dissidents. In the early 1920s he drafted his manuscript for We, an anti-Bolshevik dystopian tale, which did not pass the censors in Soviet Russia. In fact, it was the first to be banned by the Soviet censorship board. We was first published in the United States in 1924 after being smuggled out of the USSR to New York.

For history’s sake, it is interesting to note the early dissident’s correspondence with Joseph Stalin. First, Zamyatin sent the Soviet leader a request to leave Russia, which was granted. In 1934, Zamyatin wrote to Stalin again, this time from Paris, asking to be allowed back into the Union of Soviet Writers. Stalin also complied with this request, making Zamyatin the first and only emigre writer to regain membership.

The dystopian novel was also divergent stylistically. Unlike most books written by Russian dissidents, We was composed in a futurist-inspired style as opposed to more traditionalist Russian prose prevalent in anti-Bolshevik texts. This could be because Zamyatin had briefly flirted with Bolshevism in his youth and, unlike most anti-Soviets, had never been affiliated with the Tsarist White movement.

Gleb Struve, Orwell’s Russian translator who facilitated Posev’s publication of his works, introduced We to the well-known author. In 1946, Orwell expressed his admiration for Zamyatin and reviewed the English translation of We in Tribune magazine. In his write-up, Orwell noted that the anti-utopian novel’s resemblance to Brave New World was “striking” and claimed that Aldous Huxley’s book borrowed heavily from it. This is ironic, given that the plot of Nineteen Eighty-Four almost entirely matches We, while Brave New World is different from both in terms of its basic narrative structure.

Some of Orwell’s contemporaries noticed the similarities between Nineteen Eighty-Four and We, namely the Polish-British historian Isaac Deutscher. Deutscher, who featured on Orwell’s infamous list as “Sympathizer only. Is Polish Jew,” wrote that Orwell “borrowed the idea of 1984, the plot, the chief characters, the symbols, and the whole climate of the story from Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We.” Deutscher, who was a Trotskyist, viewed him as a “simple-minded anarchist” who did not fully comprehend Marxism.

However, others such as the conservative poet and author T. S. Eliot, as well as the noted science fiction author and Fabian socialist H. G. Wells characterized Orwell as a Trotskyite. Yet, Orwell himself was apprehensive; he thought that the persecution of Trotsky and his movement gave the illusion of a humane alternative to “Stalinist” communism which, in his view, obscured the totalitarian threads common to both. On the subject of Soviet Russia and the October Revolution, he wrote that one ought “to admit that all the seeds of evil were there from the start and that things would not have been substantially different if Lenin or Trotsky had remained in control.”

Deutscher noticed Orwell’s ambivalence, if not outright hostility, to other strands of socialism and how his works were used as Cold War propaganda. In other words, the author held up by some sections of the Western left today was not even approved of by an authentic Trotskyist.

It is undeniable that Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four have significantly contributed to the dominant ideology of anti-communism in the West, making Orwell’s role in history one of a literary Cold Warrior, a man who seemed to have more of a beef with Soviet communism than Nazi fascism. His publisher, Fredric Warburg, stated that, “No, I don’t think he was ever a socialist, although he would have described himself as a socialist.”

This seems accurate considering Orwell’s condescending attitude toward leftists, his pessimism regarding the cognitive abilities of the working class, and his actions. In Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four the working class is portrayed as generally stupid, uncritical, and easily manipulated. Orwell’s writing never shows the proletariat as conscious subjects of revolutionary change; rather, they are objects and tools in the hands of nefarious demagogues-turned-dictators.

The picture that emerges of Orwell is of a man whose conscience allowed him to be both a propagandist and an informant. Instead of possessing a spirit of unshakeable integrity, he was inclined to politically contrarian positions and direct plagiarism of lesser known authors. As is typical of those claiming neutrality, what is lauded as Orwell’s unwillingness to pick a side was an implicit capitulation, and even outright collaboration, with Western imperialism.

He refused to cooperate with the Popular Front to fight fascism, but was perfectly willing to supply the British government with snitch lists when the war was over. Orwell spent the era of European fascism penning criticisms of the main anti-fascist country, the USSR, showing his perception of Soviet communism as more of an aberration than fascism. The mythologized hagiography of Orwell must be amended to reveal him not as an unheeded prophet but as an emblem of pseudo-left hypocrisy, which is still prevalent to this day.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Shaenah Batterson is a polemicist and poet located in Eugene, Oregon.

She writes a Substack called The Red Letter and cohosts the podcast Captive Minds.

Shaenah can be reached at shaenahbatterson@icloud.com.

The Sorrows of Young Werther or simply Werther by Johann Wolfgang Goethe was twice thrown by the stupid Germans among the English during the two world wars.

British, especially Scottish sheepherders, who became generals overnight, did not want to read romantic nonsense, because they could put their fellow shepherd girls on their p*** already in the haylofts, and occasionally they also had fun with each other and with the livestock. False puritanism is for the public, but in the dark the British had no problem using their hand, a sheep or a colleague of either s**.

I think they described the Russians quite well and fairly at the time. But I will describe the Russians even more fairly now.

When Putin betrayed Syria and recognized the unelected Taliban psychopaths as the legitimate government of Afghanistan, he became a Putler and now there is no way back for me to ever think that Russia is ever positive. Russia will never be able to return to the right side in my eyes after these two events.

The respected Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito had the pro-Stalinist informbiro imprisoned on Goli Otok and released the rightists back into normal life because he realized that Stalin and the Soviet Union were worse and crazier than the church and the mosque.

And because he didn’t have enough space in the prisons, people sentenced to death were released and Stalinist communists were imprisoned.

As long as Tito existed, Yugoslavia existed. As soon as Tito died, Yugoslavia completely disintegrated in blood and sweat.

Since George Orwell died in 1950 it is not important for me to have a detailed knowledge of all his good qualities and bad qualities. It is enough for me to see that he did a good job of describing the great dangers of what can happen when a country has a totalitarian government. The fact that Jack has a very high opinion of him and Jill has a very low opinion of him is irrelevant to me. If Jack and Jill go up the hill to fetch a pail of water, that would be of more concern to me.