“Democracy in the U.S. has never been functional. It’s just in some laws, but it has never been implemented. There’s a huge misinformation campaign going on in the U.S., and media is manipulating people all of the time. I think the U.S. and Nicaraguan people can work together to promote peace and all human rights. You are always welcome to come to Nicaragua, and we can learn together as equals.”

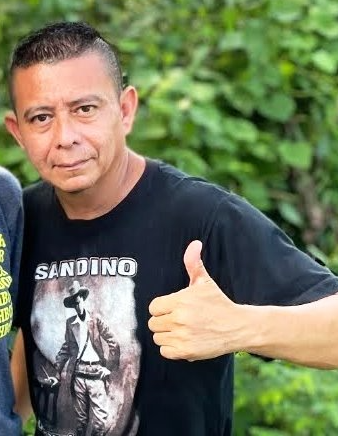

Harold “Shaggy” Urbina, Sandinista National Liberation Front

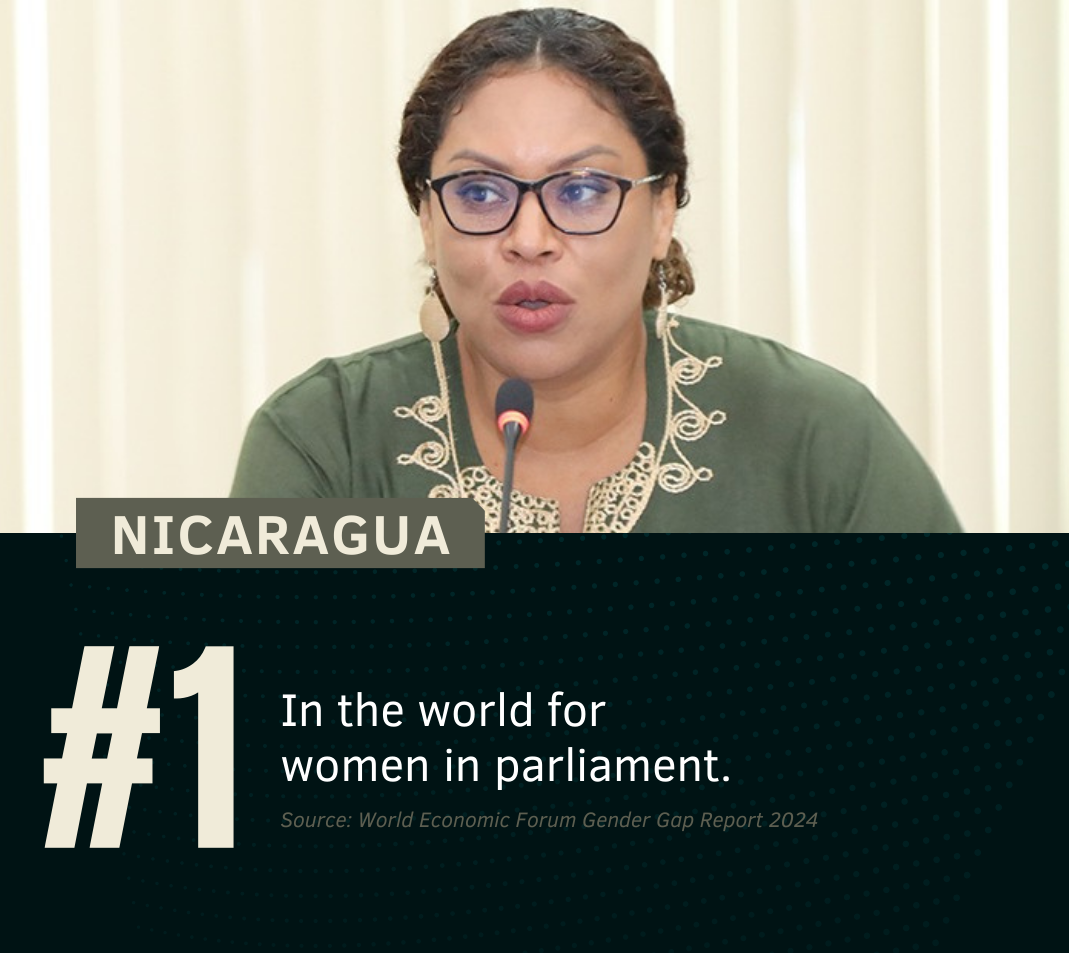

You may be surprised to learn that Nicaragua is ranked sixth in the world for gender equity by the World Economic Forum; that the government led by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) provides free, universal education and health care; and that Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples have communal title and control over lands making up nearly one-third of Nicaragua’s national territory.

Harold “Shaggy” Urbina has witnessed all of this progress and more in his 40-plus years in the FSLN, from his days as a Sandinista youth leader to his extensive work in Nicaraguan human rights organizations. “Shaggy,” as he is known by most of his friends, is currently a leading team member of Casa Benjamin Linder, which is the project for art, education and solidarity of Jubilee House Community. Linder was an American engineer who was tragically killed by Contra terrorists while working in Nicaragua in the 1980s in support of the Sandinista Revolution.[1] Among their many projects, Casa Benjamin Linder sponsors about half a dozen international delegations to Nicaragua yearly. Readers are encouraged to come see, experience, and decide what is true for themselves.

This is Shaggy’s story, as told to independent journalist and activist Ken Yale in Nicaragua in March 2025. Shaggy was six years old when the Sandinistas overthrew the bloody military dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza in 1979. Millions of Nicaraguans celebrated.

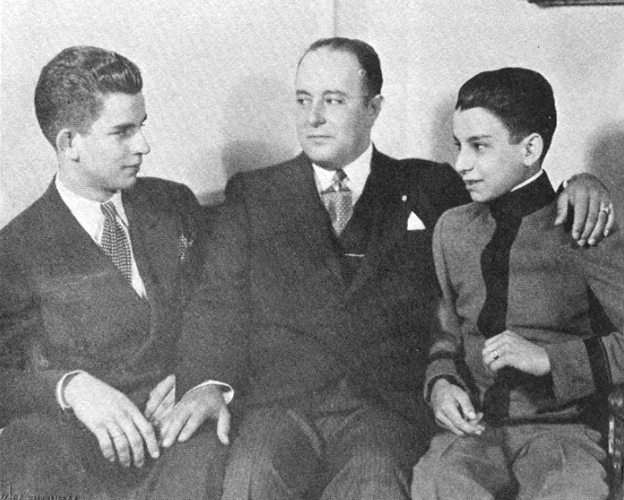

The corrupt and brutal Somoza family had ruled Nicaragua for well over 40 years with the active support and intervention of the U.S. The Somozas disappeared, tortured and murdered tens of thousands of Nicaraguans while abetting U.S. covert operations throughout Latin America, facilitating the profitable exploitation of Nicaragua by foreign corporations, and amassing huge fortunes for their family of oligarchs.

The U.S. government and its allies have relentlessly tried to destroy the Sandinista Front from the time of its triumph in 1979 through the present moment. Nicaraguans today continue to be targeted by the full arsenal of hybrid warfare, from strangulating economic sanctions, to covertly funded and orchestrated regime-change operations.

The ongoing assault on Nicaraguan sovereignty has been justified in a massive international propaganda campaign, similar to the demonization of any leader or nation that attempts to break free from colonial domination and begin the transition to a more humane or socialist society. But here is the story imperial officials and their corporate media will never tell…

The Awakening

Ken Yale: Tell us about your early political influences as a young person in Nicaragua.

Harold “Shaggy” Urbina: My father, Rafael Urbina Brizuela, was a radio announcer. My mother, Marta Cruz, has always been a housewife. My parents didn’t have a direct influence on my political life, but they were always supporting me in whatever I was doing.

I grew up in a popular neighborhood, District #2 in Managua. In 1979 we had the triumph of the revolution. I was only six years old, but I still remember that I was sent to the corner by my mother to buy tortillas. When I was there, I saw a man wearing a red and black bandana covering his face. And he said, “We won, the march to victory will never end.”

I wasn’t able to understand the political background of that moment, but I could see the happiness on the faces of the people. I could see how each person came to this man and they were all giving him hugs and celebrating. So I knew it was something very big and important. When I was walking home, I saw the parade of guerrilla fighters and I could see hundreds of youngsters on top of tanks and pick-up trucks. They were all screaming, celebrating, and people were standing on both sides of the street welcoming them.

Then I went into my house and saw my family members. They were all together around a small 12-inch black-and-white television, and I was able to see the first speech of the revolution. I wasn’t able to understand the content of the speech, but I could see the happiness on the faces of my family, so I knew it was something powerful. And I think it’s that moment I became engaged with the revolution.

Another big influence was witnessing the impact of the National Literacy Crusade in 1980. I could see my friends returning from the mountains saying, “Oh, we realized how the rural areas and the cities were separated by the dictatorship, and how hard it is to produce the gallo pinto that we eat and the coffee we drink every day.”

At that time, the Sandinista Front was in the process of making its transition from a guerrilla movement into a political party. But I understood that the Sandinista leadership was leading the revolution in the National Literacy Crusade and was also connected to another huge improvement in the lives of the Nicaraguan people, the Agrarian Reform. You can imagine how it was a huge change in the lives of people having a piece of land and being allowed to learn how to read and write.

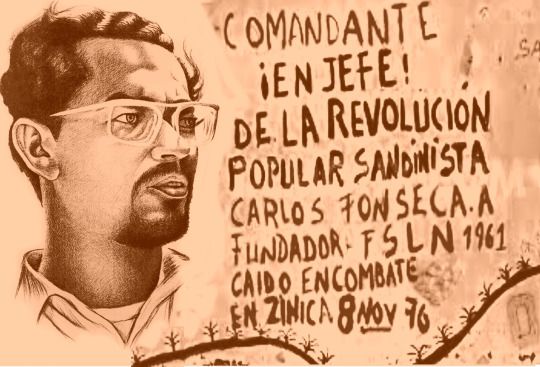

The start of the revolution was having an impact on people’s lives, and I was really happy to support that process. At school I started to learn about Nicaraguan history. I was inspired by the ideas of Sandino and Carlos Fonseca, the founder of the Sandinista Front. I was discovering a new world.

Another of my early influences was a national hero, Julio Buitrago, a 20-year-old leader of the urban resistance of the Sandinista Front. He was detected by the National Guard when he was hiding in a safe house and he asked his comrades to escape while he stayed. The National Guard thought there was a big group of Sandinistas inside. There were many National Guard vehicles outside, even a tank, and they were using a plane to bomb the house.

Somoza made a mistake, inviting the media to broadcast live the National Guard protecting the Nicaraguan population from a “terrorist group.” The house was destroyed totally, but they only found Julio Buitrago massacred alone. So this exposed locally and internationally the high level of repression by the Somoza dictatorship.

For me and most kids in Nicaragua, Julio Buitrago became a real hero. One boy against hundreds of National Guards. We didn’t care about Spider Man, Superman, Batman, or all of these cartoon characters when we already had Julio Buitrago. And that inspired me.

The Revolution Triumphs

KY: Please explain what you meant when you said that the revolution won in 1979.

HU: America is not the U.S. America is a continent, first invaded by the Spanish Empire in 1492. Central America and Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821. But it was a false independence. The European descendants of the colonizers became the new rulers of the Americas and continued to oppress the Indigenous people.

In 1823, the U.S. established the Monroe Doctrine, with the justification that they were chosen by God to protect this part of the world, and that the U.S. wasn’t going to allow any European superpower in Latin America.

In 1855, William Walker, a man from the U.S., became the President of Nicaragua with the sponsorship of wealthy U.S. businessman Cornelius Vanderbilt. They wanted to build a canal in Nicaragua to compete with the Panama Canal. Walker also wanted to export Indigenous people from Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Honduras to the southern U.S. as slaves. He was defeated by a resistance movement supported by all three countries.

The first real U.S. military intervention took place in 1910. Nicaraguan politicians were fighting each other and having many civil wars. The U.S. Marines took control of the whole Nicaraguan nation. Augusto Sandino, our national hero, organized an army of small farmers and Indigenous people to fight against U.S. intervention in 1927. Sandino talked about sovereignty, self-determination, the dignity of the Nicaraguan and the Indigenous people, and even some of the universal human rights that were not yet recognized by the world at the time. He was able to develop a guerrilla-warfare strategy and, by 1931, the U.S. forces were defeated.

But after making a peace agreement with then-President [Juan Bautista] Sacasa, Sandino and all but one of his generals were assassinated in February 1934 while having a dinner with the chief of the National Guard, Anastasio Somoza García. When Somoza assassinated Sandino, he became the President of Nicaragua. He was awarded this position by the U.S. government for completing the task it had given him. The Somoza family dictatorship oppressed and repressed the Nicaraguan people with the total support of the U.S. government from 1934 until 1979, when we had the triumph of the revolution by the FSLN.

The Sandinista Front was founded in 1961 for the national liberation of Nicaragua. General Santos López, the only one of Sandino’s generals who escaped assassination, transferred the political and ideological legacy of Sandino to the Sandinista Front. The Sandinista Front was also inspired by Marxism and the socialist ideas of the revolutions in the Soviet Union and Cuba.

We were using the tools of popular education to transfer knowledge to the people. The principle of popular education is that a community or a population that is educated can understand and reflect on the life they have, and then transform reality.

The Sandinista Revolution was also inspired by liberation theology, and many Christians became supporters of the Sandinista Front. This combination of Marxism with the positive values of Christianity, and all of the person-to-person support, based on the Christian values of solidarity, were key factors that contributed to the growth and development of the Sandinista Front in the 1960s and 1970s.

Becoming a Sandinista

KY: You’ve really given us some great personal and historical context for why you wanted to become involved in the Sandinista Front as a young person. What was the process for joining at that time?

HU: First, when I was ten years old, I decided to become a member of the Sandinista Children’s Association. I was an active member in 1983-1984. Then as a high school student in 1985, I was granted affiliation to the Sandinista Youth after serving one year as the chief of a brigade of Nicaraguan Explorers, like Scouts in the U.S. The next year, I was part of the Secondary Student Federation, and the vice president of my classroom. The following year I went to pick coffee as a member of a Production Student Brigade, to involve high school students with people in the countryside.

When I returned in 1987, just 14 years old, I won my recognition to become a militant of the Sandinista Youth. First, I was the president of a student organization of 500 students, and then at 16 years old, the president of my whole high school of 2,000 students. And I was getting ready for going to war, because in the 1980s, all of the kids between 17 and 25 years old needed to have two years of mandatory military service. I was happy to enroll in the Nicaraguan army, the Sandinista army at that time, in order to go to the mountains and defend our revolution.

I think the pride of U.S. politicians has been hurt by what Nicaragua has been able to do, being a small country. Whenever people asked me how I felt to be a Nicaraguan, I said, “I feel proud because we don’t have any U.S. military base in our territory.” That was also part of what pushed me toward becoming a member of the Sandinista Front, because this sense of sovereignty, self-determination, and dignity has always been part of the Sandinista struggle, and I have felt connected with those principles.

Finally, I received my official ID card as a Militant of the Sandinista Front in the 1990s when I was 20 years old, and I became Coordinator of the Sandinista Youth July 19 (JS19J) in the Cuba neighborhood of District 2 of Managua.

The Empire Strikes Back

KY: The FSLN lost the elections in 1990, and Nicaragua was subsequently ruled by a neo-liberal government until 2006. What is important for us to understand about this period?

HU: We were really disappointed and frustrated when we lost the elections. In December 1989, the U.S. Army had invaded Panama. The President at that time, George Bush, the father, was saying, “If the Sandinistas keep power, we’re going to invade Nicaragua as we just did in Panama.” I think many Sandinista families voted against the Sandinista Front just because they were tired of war. It was a really hard time because most of the benefits and achievements of the revolution were lost when we started having a neo-liberal government.

Back in the 1980s, we often tried to use international law to defend the revolution. We were reporting and denouncing all of the war crimes committed by the Contra forces to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The Contras were supported financially by the U.S., but they were always denying that involvement. I remember three youngsters in the military hit a plane, it crashed, and inside was a mercenary working for the CIA, Eugene Hasenfus. He was carrying hundreds of military supplies, weapons for the Contras. It was the evidence that the U.S. was involved in the war, which we took to the ICJ, and we were supposed to be compensated with $17 billion.

But when the Sandinistas lost the election in 1990, the new President, Violeta Chamorro, said, “Now we are friends with the U.S. again, so let’s forget about it. We don’t need any compensation.” But we knew in advance that the U.S. was never going to pay back anything to the Nicaraguan people.

Although we lost the elections, between 1990 and 2006, we realized that we were making the right decision in history. We perhaps were feeling lost or alone because the Soviet Union collapsed and we didn’t have any support from them in the 1990s. Then only Cuba and Nicaragua were struggling in Latin America. But suddenly, with years, we were happy to know that, in Venezuela, a new process was going on. And in many other places of the world, there was a flame that was still burning. We were receiving negative messages like “Socialism is no longer present in any part of the world.” But we never gave up. We were just being patient and waiting for new steps to be taken.

Human Rights As Collective Rights

KY: How did the FSLN continue the fight for human rights during those neo-liberal years and beyond?

HU: The Sandinista Front has always had a commitment to the promotion of human rights, because that is part of its principles and values since the 1960s. We incorporated the whole content of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights into our Constitution in 1987, a real commitment from our government to do what was necessary to improve the conditions of people’s lives.

Sandino was killed in 1934 and, 50 years later, we have the first free Nicaraguan elections, and Daniel Ortega becomes President. It’s like Daniel and the Sandinista government were the plant that was growing, and the death of Sandino was the seed that planted this process. But the right of participation cannot be reduced only to voting every five years. We were saying “No, every day, you have a responsibility as a citizen to be part of the decision-making process within your community, within your family, within your country.”

The approach of Nicaragua toward human rights is focused on collective rights rather than individual rights. In the West or in the U.S., people are always talking about freedom just at the individual level. We were working on what we call social, economic and cultural rights.

In 1990 and the years after, most of the benefits during the time of the revolution, such as education and health, were privatized. We had a high level of sexual exploitation because tourists were attracted to coming to a tropical country and having sex with young women or children. The government knew that but they were not taking any action. They were promoting foreign investors to come and do whatever they wanted to take our country. In those neo-liberal years, the government would have said “every problem in the world is going to be solved by the rules of the free market.”

For many years, I was organizing for human rights at the national level with different institutions and communities. We were demonstrating on the streets, saying “No, the rise of the people is beyond private interest.” We went door to door, asking people to join the movement for human rights. People were thinking that, when you are fighting for human rights, you need to be a lawyer or a person that knows about law. We were trying to deconstruct that myth by saying “It doesn’t matter if you don’t know the law; it doesn’t matter if you’re not a lawyer. What matters is that you go out to the streets to defend your rights.” We were always working to reach social justice, not a law or a document, something more comprehensive.

KY: That sounds like an approach to human rights called “de-judicialization.” How is this concept applied in Nicaragua?

HU: Human rights have to be seen from a multi-disciplinary approach instead of a legal approach. Laws are written, perhaps by lawyers or lawmakers, but human rights are a construction that is the result of the struggle of the people, which means the whole society. The lawmakers or the lawyers who are dealing with the specific nature of legal instruments are just part of the process. They are not the ones who make the decisions. It’s the people.

It’s like when it comes to the rights of people with disabilities, we first had a medical approach. People were thinking of them as sick people. But then we were saying “No, it’s not about a cure or giving them medicine. It’s about how we integrate these people into society so they can develop.” We’re saying, “Doctors can contribute to the health of people with disabilities. But it’s the society at large that has the responsibility to integrate, involve and accept all people with disabilities in everything.”

And that’s the same approach with human rights. We say “No, lawyers are welcome, but they are not the ones who will make laws for us. We will tell them what we want, and we will all discuss together how to do it.” It is a tradition in Nicaragua to have community assemblies to discuss any topic, and we involve most people in the community.

The Big Lessons Learned

KY: You seem to have a very family and community-oriented approach to human rights and many other issues.

HU: Yes, we have a very strong family-community structure for everything. Even when the Sandinista Front was in opposition, we promoted citizen participation and we understood solidarity as a very strong value. Selfishness is not something that Nicaraguan people like much because we live in community, we live in family, and whatever we are planning to do, it’s always thought of as a collective action. We also promote a lot of exchange of experiences between one community and the other.

After the revolution, the political culture of the Nicaraguan people changed. In some other countries, when you visit neighborhoods and say “We’re going to have a community assembly, we are going to elect a committee for water or any other social topic,” then people say “No, I don’t have time, it’s not my interest.” But here there’s a political culture that everyone wants to take part in.

That’s the main learning during the movement, that all of us have a very important role, and all of us can give a contribution. It doesn’t matter if we are not the leaders, because we, by being part, will be supporting the movement. That’s something very strong here in Nicaragua. Wherever you go, you will find that people are really concerned and participating.

KY: What did the FSLN learn about reconciliation and unity when you lost the election?

HU: When we lost the elections in 1990 and we started to work again from the grassroots level, we understood how important it was to recognize that your neighbor is your brother, your sister. Since we were coming from a period of war when the Nicaraguan society was polarized a lot, and we were able to see the division among family members, we thought “No, if you want to return to power, we need to establish partnerships and alliances with former enemies.”

Sandino was the one saying “in Nicaragua, we don’t care about conservatives or liberals. It doesn’t matter if they are from different political parties, or from the rural area or the city. We care about the whole Nicaraguan population. We are all equal.” So he was giving us this lesson, and we were thinking, “Oh, Sandino was right.”

For instance, we had a very important health project called Miracle Mission. We were in an alliance with the Cuban and Venezuelan governments, sending people from Nicaragua to have surgery for eye problems. The Sandinistas were sending the former enemies first, saying, “I will prove that I don’t have any reason to take revenge. I can see that you are sick, we will send you in our group.” They were also offering the opportunity to learn how to read and write to the former Contras and people against the Sandinista Front.

All of this movement happening at the grassroots level was changing the minds of people toward the idea they had of the Sandinista Front. Back in the 1980s, many were saying “You are all against people that believe in God because you’re Marxist.” But then the Sandinistas were saying “No, we are not against Christianity, we are not against the church.” And they started a dialog with all sectors of society for many years.

Even I was against the idea of shaking hands with Contras until I saw Daniel Ortega talking to former enemies, saying “Please forgive me.” When you see a leader doing that you understand the real meaning of reconciliation. Then we started to replicate the same action at the local level. It was complicated, but I think that for that reason, many Contras and right-wing leaders became supporters of the Sandinista Front.

In the 2006 election, the Sandinista Front registered and was listed on the ballot under the name “Alliance: Nicaragua United Triumphs,” “Allianza: Unida Nicaragua Triunfa.” That’s why, when the Sandinista government returned to power in 2007, we said, “This is the Government of National Unity and Reconciliation.”

The Fruits of the Revolution

KY: What are some major accomplishments that made reconciliation possible and helped even people who may not be supporters of the FSLN see that you’re acting in the interests of the people?

HU: Since the Sandinista Front returned to power in 2007, they have been working on a process called “Restitution of Rights.” They said, “We are going to have education and health services free of charge.” With that single action, people were able to see that we are really changing. In addition, many of the social sectors that were excluded in the past started to have a voice again and to participate. The Sandinista Front was not excluding anyone. Even former enemies were included in the social policies the government was implementing. The Catholic Church and the private companies were not supporting the government, but not attacking, which was a big change. Many right-wing people realized that they had not been getting anything from the neo-liberal government.

In a few years we were able to recover many of the rights we lost in the neo-liberal years, and people were really happy. We were growing and developing. You see that the roads that go to remote areas are in good condition, and that small farmers can take their production out of the community because the Sandinista government is building new roads everywhere. So people say, “Oh, I’m satisfied with this, and I’m not a Sandinista, but I need to acknowledge what they are doing.” The Sandinistas never said “Oh, we will do this to convince our opponents to become Sandinistas.” It has been the opposite. “No, we feel okay to live with the rest of our community. It doesn’t matter what they think, what they believe in.”

I think the local people have been able to acknowledge not just the development in the communities, but the environment of peace and safety. The Sandinista Front came back to power saying, “We will do as much as possible to keep this nation in peace. We were not able to develop Nicaragua enough back in the 1980s because we were in war.”

Citizen security in Nicaragua is a big thing, and Nicaragua is the safest country in Central America. That’s because the National Police, the National Army, and every institution in Nicaragua is doing its work based on this family-community model. Your own neighbors and the community itself are protecting you. That’s why we don’t have this penetration of the gangs from Guatemala, El Salvador, or Honduras.

There is a global movement to promote right-wing ideas. But I think that Latin America can make a difference. With the exception of the violent context in Colombia and Mexico, we have like a peace zone, countries facing their own social conflicts, but without going to the point of war. Most of the presidents of Latin America don’t want war in their own countries. That’s something we can take advantage of to promote dialogue and a way of understanding among the Latin American nations.

KY: What can you say about the accomplishments of the FSLN in terms of the role of women and their support for the revolution?

HU: The Nicaraguan revolution has been led by youngsters and women since the very beginning. Sandino’s wife was an active member of the Army for the Defense of National Sovereignty. Since then we have always been able to see the important role of women in the struggle. In our revolution, the role of women is not for decoration. It’s not an ornamental role. They have an active role and they have gained that space, not just because we have guerrilla members before the triumph of the revolution, but because when the Sandinista Revolution was in place, many women became active, participating in everything at the different levels, the same as men.

What the Sandinista Front has done from 2007 to 2025 is legalize all of the rights that women have. They won these rights by their own struggle, but now the government is offering the corresponding laws. That’s how we have many women in top positions in the ministries, the police, and the army. The majority of community leaders are women. And in the Presidency of Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo are Co-Presidents. We have a system of 50-50 for elected and appointed officials, and some spaces where women’s participation is 60 or 65%.

That’s something that makes Nicaragua different from the rest of the countries in Central America, because women are not passive. Women are not submissive. They fight for their rights. And education is important because we have been able to talk about the rights of women at a family and community level, in the school programs, and in the university study programs. So it’s something comprehensive.

I’m not saying that we don’t have problems, because we do. There is a permanent struggle against violence against women and children. That is something that is happening everywhere in the world. But here we are trying to do the most we can. Perhaps the difference can also be seen in the way we name it. In the U.S. they call it “domestic violence,” something that is happening inside your house, like a private problem. But in Nicaragua for the last 25 years, we identified violence against women as a social problem, as a health problem, a difference from other places where it’s a private thing. Here everyone has a commitment to do something when they know that there is a case of domestic violence.

Solidarity Then and Now

KY: There was a very large international solidarity movement in the 1980s. But since the Sandinistas came back into power in 2007, Nicaragua is not in the news as much, not as many activists are coming, and so I think we’re much more susceptible to propaganda from imperialists and their allies.

HU: For the first years when the Sandinista Front returned to power, the U.S. was keeping a distance and not openly attacking the Sandinista Revolution. But I think they were planning what they were going to do years later, and we didn’t know.

I have to confess something. I didn’t like people from the U.S. at all in the beginning. I wanted to go to the Soviet Union and learn how to speak Russian instead of learning English. But then I met many people from the U.S. in 1997 at a community center led by Father Grant Gallup. He was teaching me English, and how to understand U.S. culture. Christians who were following the principles of liberation theology were really supportive of the Sandinista Revolution in the 1980s, and then of the social movement against the neo-liberal government in the 1990s.

He introduced me to a man who came to visit Nicaragua for a few days who asked me, “Is it true that Nicaragua was a military base of the Soviet Union, and you and the Cubans wanted to invade the U.S.?” And I realized there was a huge misinformation campaign going on in the U.S. Perhaps that’s why many people in the U.S. were supporting the Contra war, because they were just following the information and manipulation of the U.S. government. I realized there was a difference between the U.S. people and the U.S. government, and I started to be open to people from the U.S.

Perhaps that’s another reason why the U.S. is scared of Nicaragua. We are a model that can teach others how things can work. I think democracy in the U.S. has never been functional. It’s just in some laws, but it has never been implemented. The struggle of the U.S. people has always been oppressed by the big corporations and the system itself. The example of the success of the Nicaraguan people could threaten them.

We understand solidarity as a value. We received a lot of support since the revolution from foreigners, individuals or organizations that came to Nicaragua. I am currently working with a lot of solidarity groups and volunteers who come from the U.S., Canada and the UK to support the Nicaraguan people.

During the last 20 years there has not been enough information available in the U.S. about what is going on here in Nicaragua. After the attempted coup d’état in 2018 and then the COVID pandemic, it has been more difficult for us to bring people from Europe and the U.S. to visit. Fewer people are coming and it’s harder for us to find ways to share information.

We need a generational replacement of the solidarity movement, because many of the really strong and committed people are taking care of their own health. They are not as young as they were in the 1980s. We know that we need to transfer these values of solidarity to the new generations. But I think that step by step we will get it.

I think the U.S. and Nicaraguan people can work together in order to promote peace and all human rights by having what I would call a permanent “Learning Agenda,” a space where we can learn with each other as equals, instead of one on top of the other. If we have a way of exchanging experiences, and having people from the U.S. visit to see how our revolution is going, perhaps they can change their opinions. The media manipulate people all of the time, especially in recent years, and it is important for people to go outside the U.S. if possible. You are always welcome to come to Nicaragua, and we can learn together as equals.

Profound gratitude to Roger Harris for his support in helping to edit this interview.

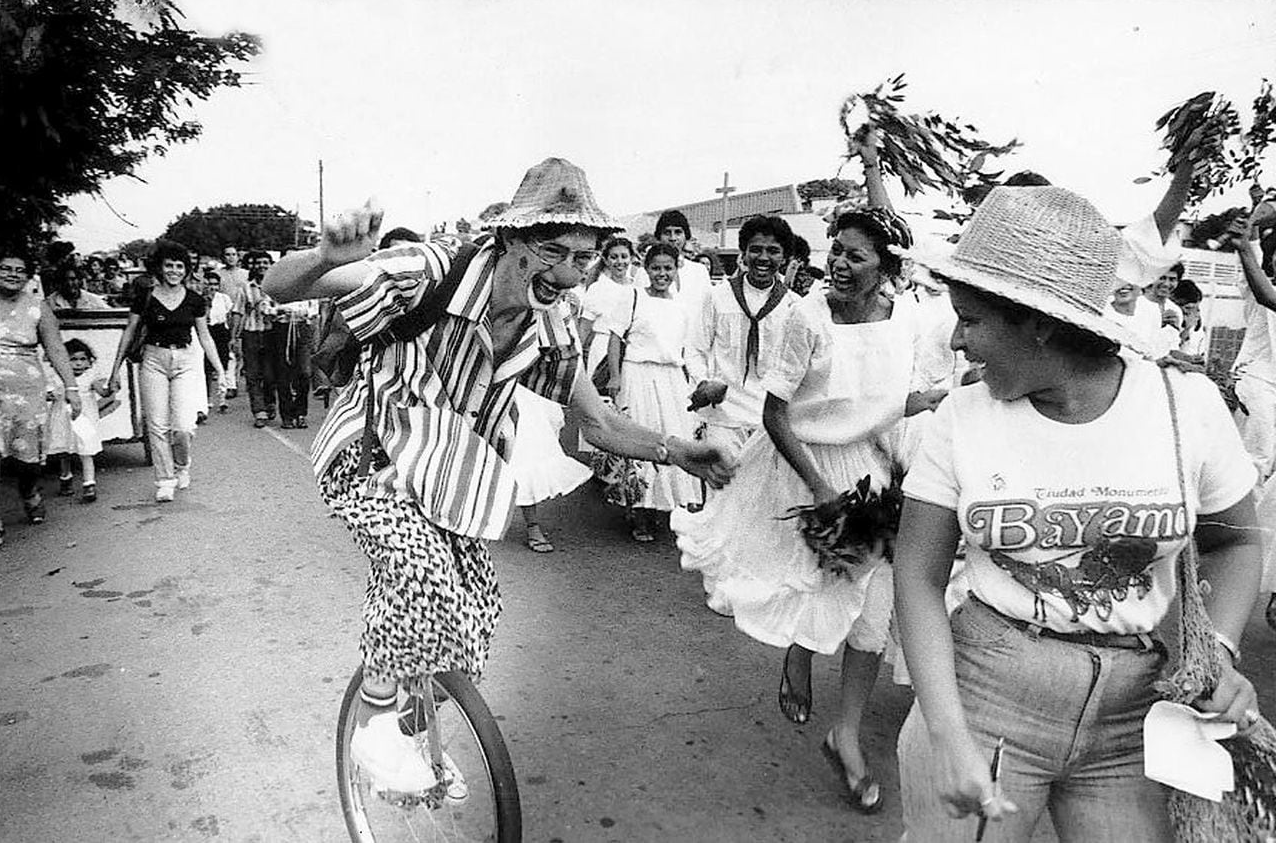

Linder had worked on Nicaraguan hydro-electric projects and a Sandinista vaccination campaign. He was beloved by the many children he entertained as a clown and juggler. He was assassinated in 1987 at the age of 27 by Contra death squads trained and funded by the U.S. government. For more about him and the circumstances of his death, see Joan Kruckewitt, The Death of Ben Linder: The Story of a North American in Sandinista Nicaragua (New York: Seven Stories Press, 1999). ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Ken Yale is a social justice activist, educator, and independent journalist living in the San Francisco Bay Area.

He recorded this interview in March, 2025, while participating in Casa Benjamin Linder’s international delegation to learn about the empowerment of women in Nicaragua.

As a social justice activist for over 50 years, Yale has focused on building solidarity in the U.S. with international movements for national liberation and socialism in Latin America, Africa, and Asia; organizing white North Americans to build solidarity and alliances with the liberation movements of people of color within the U.S.; and building support for feminist and LGBTQ movements.

He is currently a member of Jewish Voice For Peace and the Black Alliance For Peace Solidarity Network. Yale recently retired after a 40-year career as an educator, specializing in using alternative and popular education pedagogy, primarily with students who were failed by their school systems. He is also an independent journalist, most recently a producer for several programs on the Pacifica Radio network.”

The Jewish Voice for peace which praised the October 7 massacre by Hamas only represents a tiny percentage of the Jewish people.

https://www.standwithus.com/post/jewish-voice-for-peace-jvp-report

Nicaragua’s high ranking in global gender equality indices is misleading because it primarily reflects women’s standing relative to men within Nicaragua, rather than an absolute measure of women’s well-being or equality compared to women in other countries. While Nicaragua scores well on indicators like political empowerment, this doesn’t necessarily translate to significant improvements in women’s lives or address persistent issues like gender-based violence and economic inequality.

Nicaragua’s ranking on freedom reports is consistently low, particularly concerning political and civil liberties. For example, in the 2022 Freedom House report, Nicaragua was rated as “not free” with a score of 14 out of 100. Reporters Without Borders ranked it 160th out of 180 countries for press freedom in 2024. This indicates a significant decline in press freedom, with the closure of media outlets and the exile of journalists.