When I was young, my parents worked long hours. As a result, I spent much of my childhood with my grandparents, whose outlook on life always fascinated me—though at times, it left me deeply unsettled. Their time was not my own; it always moved more slowly, as if our clocks were never synchronized. A conversation was never brief. There was always a weight to their words, as if each one carried its own personality and history.

This insatiable curiosity was universal, but it centered on my grandfather, whose trips into the past were infinitely more compelling than my math lessons, to which I scarcely paid attention. I knew he had been to war and that he had written a book about his time there—in the jungle, fighting what his comrades called “terrorists,” a term he still avoids using to this day. I must admit, however, that I was not much of a reader back then. I far preferred to hear the stories first-hand, free from any preconceived notions.

Over the years, I committed an endless catalogue of his stories to memory. He told them not out of boastfulness or nostalgia, but because I kept asking. And I continued to ask until I felt there was nothing left to uncover—until I finally realized that his memory and his trauma made it impossible for him to be precise, or even entirely truthful.

As an adult, I asked my father if there was anything I didn’t know—something lost in the fog of memory. After all, he had heard the same stories I had, over an even longer period. And as it turned out, there was.

Just months before Angola’s long-awaited independence, a rage fueled by ethnic and ideological differences erupted among its people, plunging the country into a prolonged and bitter civil war. Three major factions—the MPLA, FNLA, and UNITA—clashed for control of the land and its people. News of the escalating tensions reached Portugal and was met with deep apprehension. After years of armed struggle, Angola was once again being dragged into war—this time, a fratricidal conflict with international repercussions. With the Vietnam War over, Angola became the center of the world, the heart of the Cold War.

That heart beat fiercely, especially in the chests of the Portuguese who had grown accustomed to calling Africa “home” and were now forced to abandon their way of life. It also beat in the hearts of the former soldiers who questioned the futility of the years they had spent in the bush, fighting for control of the land and against the communist threat. Neither group could bear the thought that everything they had fought for was now on the verge of collapsing into anarchy.

Though my grandfather was a devoted “socialista”—in Portugal, this essentially equates to European social democracy—and a fierce critic of Portuguese and Western colonial policies, he was also an anti-communist. Or rather, he became one after a neighbor he deeply respected warned him of what would happen if the communists seized power. “We recognize no friends,” the man told him gravely.

The events of the Hot Summer of 1975 and the outbreak of civil war in Angola were the final straw. It was time to pack his bags and set sail once more—this time, back to Angola. He felt compelled to join those now believed to be the only faction capable of stopping the MPLA and holding Luanda: the very same men who, in 1961, had slaughtered his countrymen and sparked a 13-year war.

But if, in the end, common sense prevailed—and my grandfather never set foot in Angola again—the same could not be said for so many others. They turned this new fight into an extension of the war in which, years earlier, they had watched so many of their comrades die. This is their story.

This is one of those moments when, as a journalist, a time machine would be invaluable. While historical records are detailed enough to reconstruct the broad events of the past, it falls to me—and to the reader—to imagine the true chaos and volatility that must have gripped Angola in the months following the signing of the Alvor Agreement. This accord was meant to establish the terms for power-sharing among the three aforementioned movements after independence.

Truth be told, I was not entirely sure where to begin my research. I searched everywhere, but initially found nothing. Information exists in abundance, yet it is profoundly scattered. Many are aware of the presence of a Portuguese contingent within the FNLA’s ranks, but few know the names or the true motivations of the men who constituted it. The trail is made of scant, disjointed references, scattered here and there.

“How?” I asked, desperate. “How is it possible that there’s no available information to write an article about this?” It was as if history itself was playing a game of cat and mouse with me. Over time, it would drop a clue here and there—but nothing substantial, nothing that truly satisfied me. I needed something concrete.

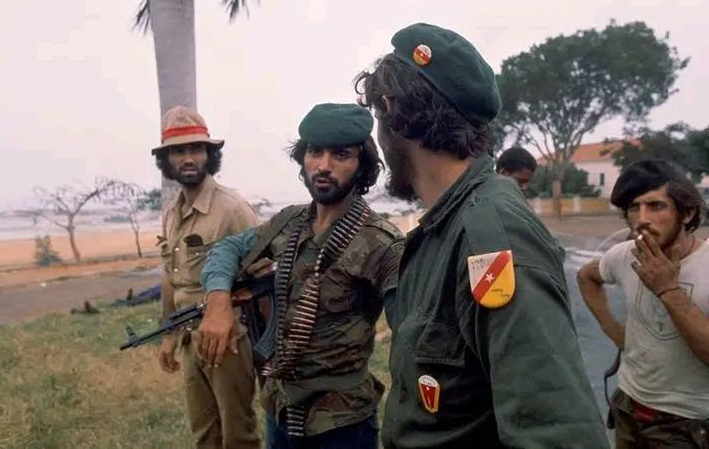

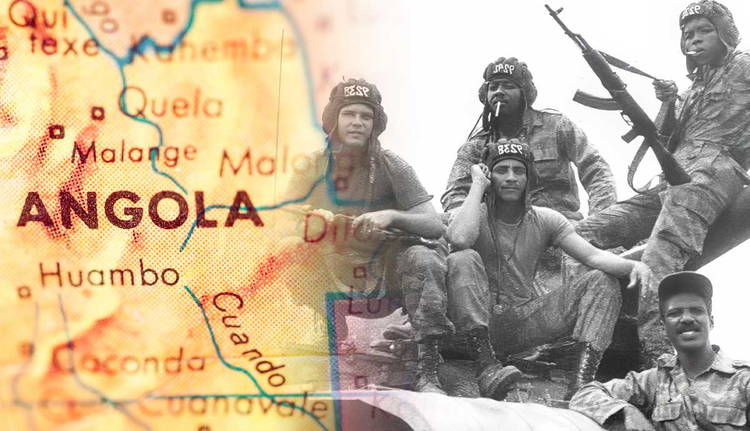

I began by carefully examining the photograph that had sparked this entire pursuit. Anyone who delves into this subject will inevitably come across it. Though it is not the only image depicting Portuguese commandos fighting for the FNLA, it is by far the most revealing — in every aspect: clarity, detail, color and context.

In it, three poorly uniformed soldiers are seen intently watching a fourth man, who grips a machine gun with a bandolier slung across his chest. Military decorum has been entirely abandoned. All of them sport unkempt beards and long hair— some curly, some straight, but all long. Were it not for the insignia of the Commando Regiment (RCmds) visible on one man’s shirt, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to discern their nationality. For all I knew, they could have been Cubans. But no—they were all Portuguese. Or were they? We’ll return to that question later.

Behind them, between the low brush and a sky blurred by the humid heat of dusk, hangs a reddish haze—the kind you would expect in an African landscape. But those men were not there as tourists. Their faces radiate a latent tension, the restlessness of men prepared to kill or to die. Portuguese or Angolan, soldiers or mercenaries, idealists or cynics, heroes or occupiers—all are merged into a single, frozen moment.

Instead of following the money, I chose to follow the trail of intrigue, carnage and blood that marked Portuguese involvement in the Angolan civil war. In mid-August 1975—a politically febrile month—Diário de Notícias reported the arrival of Portuguese “mercenaries” in Nova Lisboa (now Huambo), who had come from Rhodesia to join the troops of Holden Roberto, the FNLA’s supreme leader.

The use of the term “mercenaries” was no accident. On the contrary, it was meticulously calculated down to the smallest detail. It stemmed not only from the premise that these men had taken up arms purely for financial gain but also—and above all—from the unshakeable conviction of the article’s author in the truth of that interpretation.

Tensions were at a boiling point. The atmosphere in the newsroom was as turbulent as the streets outside, where parties, associations and activist groups vied for popular support. While some fought for editorial pluralism, others were primarily concerned with preserving the revolutionary fervor beyond those four walls.

This latter faction, led by the then-deputy editor—and future Nobel Prize in Literature recipient—José Saramago, was responsible for purging 24 journalists. All of them had openly opposed the editorial direction; all of them faced the consequences.

It is no surprise, then, that for those who adopted this stance, any Portuguese national fighting in Angola during the independence process could only be deemed a mercenary. That, and the fact they were fighting against the party they supported: the MPLA.

“Only I have the key”

Twenty hours had passed since John Stockwell, the CIA’s man in Angola, landed in Ambriz to meet Holden Roberto—a man he had met the day before, but who had paid him little attention. His objective was to discuss the details of his mission. Washington was completely in the dark. After the disaster of Vietnam, there was no room for error. It was imperative to assess the situation on the ground to determine how the U.S. could counter the growing Soviet influence in the country.

He had been instructed to pose as a journalist. After all, it is one of the professions most akin to espionage—whether in gathering information or dealing with sources. But in the world of spies, nothing ever goes exactly to plan.

The trip to Ambriz was the first of many failures and disappointments. The FNLA command had not been warned of his arrival and was deeply skeptical of his credentials. It is hard to say—even he could not be sure—whether the soldiers suspected he was a spy or simply wanted to keep the events there a secret.

Flanked by two Portuguese commandos, their machine guns at the ready, the Angolan officer warned him that he would be arrested and all his equipment confiscated. There was no turning back now. It was time to confess what he was really doing there.

“I am not a reporter, not a tourist, and certainly not a missionary. I am a colonel in the service of the United States and a personal representative of Dr. Kissinger. President Roberto himself invited me to Ambriz to take all necessary photographs for my mission. He will be here tomorrow to show me your camps and your forces,” he later recounted in his book, In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story.

The tension eventually subsided. Stockwell was then driven by jeep to an abandoned beach-front house, where he could finally savor the “indescribable pleasure” of a cold beer. After all, even spies must indulge in the finer things. Humble and weathered as the place was, it now served as the FNLA’s new central command post, following their expulsion from Luanda by the MPLA.

Portuguese commandos moved frantically in and out, as if the world were ending. And perhaps it was. What would become of them—white men of Portuguese descent—if the MPLA seized power? What fate awaited those who stayed out of the conflict? How would they be received after the war if they chose not to intervene? And what of their families? Questions without answers.

While it is true that some of those men were there to avenge the lost empire, most had been born in Angola. They were white Angolans. They had fought alongside Portuguese forces, only to now find themselves fighting under the FNLA flag against the MPLA. Only history will ultimately be able to judge the reasoning that motivated them, for I, try as I might, cannot do so.

Soon, one man broke away from the chaos and approached Stockwell. A Captain Bento. The name alone evokes a superhero, and to those men—desperate for reassurance—perhaps he was. But to history, he remains just a rank and a surname; a footnote.

Despite my efforts, I never uncovered his first name. For those of us who seek to memorialize every name, every date, every detail, this omission is deeply frustrating. As a reporter, I need to anchor actions to a person, not an abstraction. Yet, for those who believed in his cause, this is how legends—how myths—are born.

Bento was assembling a commando unit of white officers and black troops.

“Africans are too stupid to lead anything, though they can be moulded into decent soldiers,” he told Stockwell.

He said it loudly, knowing full well who might hear—including the African commanders he held in such contempt. For some reason, he felt compelled to make one thing clear to the American: He and his men were far superior to the FNLA troops. Though they fought on the same side, Stockwell needed to understand the distinction.

Bento knew this visit would yield reports. And in a war where the names of the dead mattered, he could not afford to be just another faceless soldier.

One by one, they came—stealthily—to speak with the CIA’s golden boy. Suddenly, everyone had an opinion to share. After Bento, it was “Falstaff,” another man well-versed in the shadowy world of international espionage. Ten days later, back at headquarters, Stockwell stumbled upon a curious detail: This so-called Brazilian journalist had once been a CIA asset. Without being asked, “Falstaff” had already filed his own report. Old habits, it seems, die hard.

“Be careful. Captain Bento and Colonel Santos e Castro are rivals. Forty Portuguese army veterans joined the FNLA. In truth, they’re Angolans. White Angolans. They don’t take money from the FNLA. They fight for their homes and businesses, for the only life they’ve ever known.”

Stockwell had heard this speech countless times. It was worn thin. Whether the American spy fully realized it or not, the information “Falstaff” had given him was already becoming obsolete. While these fighters had initially operated as unpaid volunteers, that changed as CIA funds began to flow—transforming them into salaried operatives of the West’s most powerful intelligence agency.

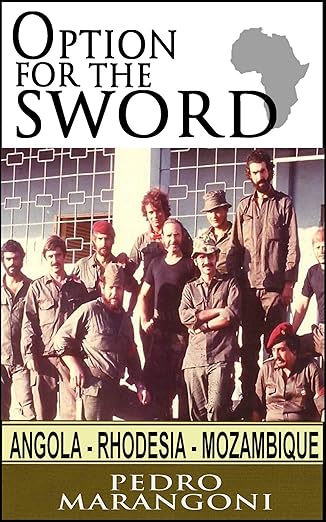

Pedro Marangoni, a Brazilian veteran embedded with this contingent, captured their mindset in his 2020 memoir The Sword’s Choice—a raw, first-person account of foreign fighters in Angolas civil war:

“We came to Angola to guide its transition from colonial rule to its premature yet inevitable independence, to prevent its subjugation by the USSR—that voracious bear ever ready to devour newborn nations. We did not come to kill, but to fight an enemy. We never felt like mercenaries, though we were paid to fight. We were not outcasts acting out some grudge against society.”

Yet it was over a “modest meal” of dried fish and boiled potatoes that Stockwell grasped how Africa’s intricate theater of war could be upstaged by clashing egos. As Holden Roberto was as notorious for his tardiness as for his military strategy, the men ate without ceremony before their leader’s arrival.

The dining room hummed with a tension sharp enough to draw blood. At one end sat Bento and “Falstaff”; at the other, the formidable Colonel Gilberto Santos e Castro—architect of Portugal’s elite Commandos. Stockwell knew him only by reputation: a squat, bald fireplug of a man he had never actually seen until now.

Silence swallowed the meal whole. There was only the crash of waves and the coastal wind whistling through the cracks. When Stockwell ventured a question, Santos e Castro pretended not to understand English, staring fixedly into his plate. All waited—for the colonel’s wisdom, for Roberto’s arrival. Neither came.

After dinner, Stockwell retreated to the veranda. Alone in a wicker chair, he replayed Angola’s dissonant melodies as sunset bled into night. Shadows stretched like grasping fingers. Then—movement. A silhouette, warped by darkness. His pulse spiked. An infiltrator? Would his mission end in some abandoned house, his body left for the jackals?

The figure advanced calmly. A candle flared in one hand; the other tossed a scrap of paper into his lap: “Please come see me. This man will guide you—Castro.”

So, he did speak English.

Stockwell’s gut screamed trap, but spies must sometimes betray their instincts. He followed the guide through two shadowed blocks to what resembled servants’ quarters—chaotic, claustrophobic. Before he could steady his breath, Santos e Castro emerged from the gloom.

“I’m surrounded by ambitious fools,” the Portuguese spat, frustration etched in his candlelit face.

The flickering light sculpted his sharp features into something cinematic—a villain’s monologue in some noir thriller. But here, heroes and villains wore the same mud-caked boots. The crashing waves nearly drowned his conspiratorial whisper:

“Everyone wants Angola…but only I hold the key. Without me, they have nothing.”

Like many of his subordinates, Santos e Castro was a man of paradoxes—a living contradiction. His grandfather had settled in Angola before the turn of the century, when the territory’s white population numbered barely a few thousand souls scattered across a near-impenetrable wilderness.

This lineage made him a third-generation Angolan. Though raised in Luanda—the heart and soul of Angola—when forced to choose sides, he pledged allegiance to the Portuguese colonial army, fiercely conscious of the Lusitanian blood in his veins. Later, he would ascend to governor of Uíge Province, becoming a chief enforcer of Lisbon’s iron-fisted policies to maintain control. Such are life’s ironies…

But what was this “magic solution” Castro so fervently believed in? Six hundred Portuguese army veterans, stationed in South Africa, awaited his order to unleash chaos and retake Luanda once and for all. All were men he trusted; all were white Angolans. Yet it was a classic case of military hubris—the old fantasy that a handful of seasoned soldiers could conquer a nation.

Of course, none of this would be possible without vast sums of money. And who better to bankroll such a campaign than the CIA? After the debacle of Vietnam, the U.S. government desperately needed a win—something to justify its investments in Angola’s anti-communist struggle. Santos e Castro knew this and leveraged it masterfully.

Beyond funding, the colonel made uniquely self-interested demands: His rival, Captain Bento, must be cut out of decision-making entirely, and Holden Roberto reduced to a mere figurehead. What he truly meant was that from then on, the war’s fate would rest in his hands alone—and if the CIA held up its end of the bargain, he would deliver results.

Fortune favors the bold

After a brief visit to the FNLA’s communications center in Ambriz, Stockwell returned to find Captain Bento drilling a mixed-race commando unit. Observing them, the spy—a former soldier himself—concluded it would be unwise to bet everything on the Portuguese. They were determined but clumsy, skilled only in guerrilla warfare and unprepared for what lay ahead. With time against them, even a year of training might not be enough.

Suddenly, the shriek of a Panhard armoured car’s brakes startled the men. Holden Roberto had arrived with his entourage. He might not have been a gifted strategist, but he knew how to make an entrance. Before Stockwell could process the scene, Roberto ushered him into a Volkswagen van. No explanation, no destination—just an order masked as an invitation.

Three white men joined them. Only one was Portuguese: “Chevier”—clearly an alias. Tall and burly, likely a former paratrooper turned commando, he struck Stockwell as someone far more significant. And indeed he was: the ex-chief of Portuguese intelligence in Luanda. Now, like Santos e Castro, he offered his expertise to the very men he had once called enemies—men he would have gladly killed in another life.

After a brief stop at Roberto’s forward command post—Lifune Farm—the convoy rolled on.

“We’ll be in Luanda soon,” Roberto declared, brimming with vain confidence.

History has a way of endowing political leaders with a blind, stubborn certainty—a kind of drunkenness of spirit that clouds judgment. Holden Roberto was no exception. “Roberto didn’t know what he was doing,” Stockwell recalled. “He refused advice and created as many problems as he solved.”

His bravado made the American spy’s job nearly impossible. How could he draft any credible report for Washington when the FNLA leader insisted on exaggerating his troops’ feats and impact? The truth was, Roberto could not distinguish a skirmish from a real battle—a fact laid bare by his glaring absence from any front line, his life never truly at risk.

From Lifune they pushed north to Caxito, a town that had fallen to the MPLA the previous month. The communist offensive had been savage, leaving deep scars on the survivors. The images haunted even seasoned soldiers: women, children, drunks, and addicts—the so-called “people’s power”—charging unarmed toward Panhard armoured vehicles, fully aware of their fate.

The fighting was carnage beyond comprehension. Ferried to the front in aging Portuguese Air Force helicopters, these red martyrs must have seemed like specters—ghosts descending from the sky to torment Roberto’s men. “It was impossible to stop such a tide of fanatics,” Pedro Marangoni wrote. “They advanced drunk over corpses, never breaking stride.”

Here was that timeless horror: the shock of irrational, chemical-fueled violence. Perhaps Soviet soldiers felt it on the Eastern Front, staring into German eyes and seeing men no longer in control—just as the Nazis had marched through ice and pain, hopped on D-IX’s cocktail of meth, cocaine, and oxycodone.

That day, four of the twenty white commandos fell. One, Machadeiro, died instantly. The others were captured. Years later, I would find the photo of their detention online—the very evidence I had sought. At last, I saw the faces of the men I aimed to document: war-haunted, utterly unlike the defiant portraits I had described before.

Every detail in that grainy image reeked of tension and defeat. Filthy bodies and frayed uniforms spoke of exhausted combat. Eight men stood in two distinct postures: four with hands bound behind their backs, others crossing their arms— different ways to face surrender?

Only three were white: Quintino, Fernandes and Pereira. Their eerie calm stood out starkly in the monochrome frame. Why so composed? They likely believed this was their last day on Earth. Survivors scattered in small groups, retreating to their base. Caxito had fallen.

The MPLA rushed to parade their victory before the international press. Beyond flaunting military dominance, they exposed the FNLA’s collusion with America—flipping open CIA ammunition crates stamped with the USAID insignia.

Only then did the FNLA and its allies grasp the obvious: A handful of men could not retake Luanda. Reinforcements arrived—Zaire’s Mobutu, FNLA troops, white commandos—pushing the MPLA out of Caxito in a coordinated assault.

Together, they torched Soviet-made armoured vehicles, watching crews burn alive inside. There were no mercy kills here—just slow, screaming immolation. Those not consumed by flames were impaled by shrapnel. The asphalt became a grotesque gallery: torsos severed from arms, waists disconnected from the legs that once carried them.

24 kilometers from the capital

The slaughter—that senseless barbarity—left Holden Roberto practically giddy as he showed Stockwell the wrecked jeeps and captured weapons. To all present, it was clear: Roberto was dead set on taking the capital. His military inexperience and swollen ego mattered little; as long as his manic enthusiasm translated into victories, the CIA had no complaints. By all appearances, they had backed the right horse.

Luanda was no longer a mirage. For a fleeting moment, the men convinced themselves their luck had finally turned. Given the triumvirate’s military gains, it seemed plausible. What they did not—and could not—know was that everything was about to change. Catastrophically. With independence looming, hatred festered in these men, their hearts hardening as they steeled themselves to free Angola from its oppressors at any cost.

The offensive roared ahead. The men rejoiced; their families even more so. The war’s end meant these fighters—especially the white Portuguese commandos—could return to the lives they knew: existences built on land not truly theirs, nourished by blood not their own, yet from which they had reaped comfort and privilege in abundance.

But confidence is as treacherous as it is seductive. It can exalt just as swiftly as it blinds—and it was this very hubris, this almost childish stubbornness from Roberto and the CIA, that fatally delayed their advance.

Stockwell argued for capitalizing on their momentum, urging Washington to ramp up logistical support. Small arms were not enough—they needed to match fire with fire. Had they listened, America—that great “exporter of democracy”—might have prevailed. With Luanda so close and the MPLA faltering, time was bleeding away. Heavy, cutting-edge weapons were their best—perhaps only—shot at victory.

Yet some rejected this approach outright, for it contradicted the official narrative. Even after being exposed as the FNLA’s prime backer, the CIA flatly denied direct involvement—a lie that jeopardized everything. Instead of decisive action, they opted to flood Angola with spies. Controversial? Certainly. But it is easier to hide a spy than a mortar.

Nshila wa Lufu (The Road of Death)

Just kilometers from the capital, an armoured column advanced confidently after crushing MPLA checkpoints. Backed by a hundred white commandos and two Zairian battalions, the FNLA was poised to achieve the unthinkable. Only the Quifangondo Valley remained.

But the MPLA had better equipment—and Cuban advisers who brought discipline and heavy artillery.

At dawn on November 10, 1975, a hail of Katyusha rockets slammed into Quifangondo’s approaches, where the FNLA had expected another easy rout. Salvos tore the sky apart, raining death. Grenades, rockets, mortars—the barrage was unrelenting. Shrapnel filled the air. Panic spread like wildfire. Everywhere, men fell—dead, wounded or frozen in shock. The earth turned crimson, saturated with blood.

The once-proud Panhards were now smouldering husks, spewing charred, mutilated corpses. After hours of fighting, the commandos had not gained a single kilometer. The Zairians, far from helping, broke ranks—cowardice and desertions gutted the allied force.

The operation’s outcome hinged crucially on the Portuguese-born soldiers. Yet capricious fortune refused to smile upon them. Faced with the MPLA’s impregnable resistance, both the FNLA and the white commandos retreated. Though some men insisted on fighting to their last breath, the irrefutable, cruel truth remained: The war was lost. Nothing more could be done.

The clock struck midnight. After centuries of torture and oppression, the long-awaited day had arrived: November 11, 1975, Angola’s independence. Those granted this freedom scarcely knew what to do with it. They were mired in a brutal civil war, each side praying the enemy would be erased by artillery fire—growing ever closer, ever deadlier.

Meanwhile, Portugal’s High Commissioner had fled, acutely aware of the dangers of staying. Had he remained, no one could have guaranteed his safety. He would have been defenseless prey, encircled by starving lions.

In Luanda, no outside observers or professional reporters were needed. When the hour came, the MPLA proclaimed the People’s Republic of Angola as the nation’s legitimate representative. Celebratory gunfire erupted everywhere. Emotion and enthusiasm overshadowed all else—even the war.

All or nothing?

If Quifangondo’s rout shocked most, for men like Stockwell, it was an inevitability foretold. He had repeatedly warned of the disastrous consequences of neglecting advanced weaponry; he had flagged the FNLA and Portuguese commandos’ glaring lack of preparation; he had quickly discerned Holden Roberto’s avarice; he had questioned his own presence in this theater of war. With bitter clarity, he knew all was irrevocably lost.

The Soviets’ indifference to cost had secured the MPLA a resounding victory. Despite being outnumbered, communist forces—like Spartans at Thermopylae—repelled Roberto’s troops and thwarted the desperate American eagle. So desperate, in fact, that Washington nearly reversed course, considering sending more—and better—arms to help the FNLA turn the tide. But it was too late. Most funds had already been devoured by the war.

Like a magician pulling rabbits from a hat, the CIA now aimed for a similar feat. With scant remaining funds (roughly $7 million), they recruited mercenaries: 20 Frenchmen and 300 Portuguese—a peculiar ratio. Stockwell balked at the French, but the Portuguese recruitment unsettled him more. Why enlist the defeated, fresh from losing their colonial grip?

Yet the plan proceeded, undeterred by misgivings. If this saga has taught me anything, it is that stubbornness can be perilous—especially when it defies the natural order. Once again, the CIA turned to Santos e Castro, meeting him in Madrid in early December 1975 to discuss how he might tip the scales and alter history’s course.

Three hundred men. That was all Santos e Castro claimed to need. This time, they would not just be white Angolans but also Portuguese veterans—men torn from their homeland by a 13-year war that stole mothers’ sons and fed them to Angola’s humid jungles.

Before condemning his men to a fate worse than death—the abyss of perpetual war—Santos e Castro ensured he would not suffer another Quifangondo-style humiliation. Stockwell noted the colonel secured a Swiss bank account, into which the CIA deposited $55,000 for operational costs and another $55,000 for “airfare, salaries, bonuses, Angolan upkeep, and medical expenses.” At last, he had the means he believed he was owed.

To this sum—approximately $1.5 million—was added a $25,000 commission for Santos e Castro himself. He, the renowned military man, would be Angola’s savior from the communist spectre. Yet the keys he claimed to possess would prove faulty. The recruitment process began too late, aiming to stem the FNLA’s collapse in northern Angola. Santos e Castro had promised the CIA 300 men but, as time passed, it became painfully clear this pledge had been wildly exaggerated.

When pressed about delays, he retorted that December’s approach—with its holiday disruptions—complicated everything. He added that he still needed to establish infrastructure for his “small army.” Unsatisfied, he demanded additional funds, a request the CIA denied. Caesar’s wife must not only be virtuous but appear so—and Santos e Castro was now held to that standard. Accountability was non-negotiable: If he provided a roster of recruits and justified the $110,000 already disbursed, funding would continue.

In true Portuguese fashion, Santos e Castro told them to bugger off. Stubborn, he insisted justifications were unnecessary. Total freedom had been promised, he argued, so long as he delivered 300 soldiers to Kinshasa. The CIA, unamused by his obstinacy, froze payments immediately. Financial pressure forced his hand. Reluctantly, he furnished names—13 in total.

The northern front hung by a thread. The FNLA needed every ounce of support. There was no more time. Repeated delays forced the CIA to abort the mission. The 13 men were shipped back to Europe without ever setting foot in Angola. Perhaps it was for the best. What could they have done there? If the white commandos had stayed out of patriotic duty, these men were driven by money and vengeance — a volatile, dangerous mix. Now, they could truly be called mercenaries. Santos e Castro—the man who, in the end, held no master key; the self-styled Angolan Leonidas—was finished.

Any hope of toppling the MPLA had died at Quifangondo. What followed was the slow unraveling of inevitable defeat, marked not only by battlefield bloodshed but by war crimes that defied any code of honor. Among these atrocities looms the massacre of Maquela, where a deranged English mercenary slaughtered 14 of his own comrades and 160 Angolans, most of them FNLA loyalists.

Let no one believe the British alone followed orders that history will never absolve. Among the hardened faces of war were also Portuguese veterans—men accustomed to gunpowder and rotting corpses. One, known as “Uzio,” drove a truck carrying FNLA prisoners to their execution. Behind him, in a second vehicle, another Portuguese manned a heavy machine gun, its barrel ensuring no one—not a single soul—dared escape the fate decreed by their own comrades, now surrendered to the sadism of a war so desperate it devoured its own.

By February 2, 1976, the few Portuguese remaining in Angola had been stripped of humanity. They fought merely to fight, devoid of honor or purpose. As I lay down my pen, I close my eyes and picture that Portuguese soldier behind the machine gun. What crossed his mind in that moment? Staring at former comrades—condemned on a whim—did he wait for them to run before gunning them down like defenseless prey? Where is he now? Did he have children? And if so, did he ever tell them what he did? I pray not. What trauma, what horror could a child bear, knowing their father was a murderer?

A farewell song

Knowing their efforts had failed and Angola was beyond saving, the CIA resolved to close this chapter for good. They chose to compensate those who had fought on their behalf—but hesitated at Santos e Castro’s name. He knew too much, yet had already taken too much. He had promised the world with no intention of delivering it. Still, he demanded more.

Claiming he had convinced 126 men to quit jobs in Portugal for the front before recruitment was halted, he insisted they deserved compensation—despite zero proof these men existed. The CIA capitulated, granting him an additional $353,600. Months later, from Spain, he would still argue the agency owed him.

The truth is, contrary to what has been written before, Santos e Castro’s boundless ambition far surpassed that of movements like the ELP (Portuguese Liberation Army) or the MDPL (Democratic Movement for Portuguese Liberation).

As far as can be determined, the Portuguese officer saw the rivalry between these groups as a monumental waste of time. His aspirations transcended mere ideology—he sought nothing less than to overturn Portugal’s political order itself. Perhaps that explained his insatiable need for funds.

According to Pedro Marangoni, the two men even conceived a plan to stage a coup in Portugal, aiming to restore what they believed was the nation’s stolen grandeur. They called this scheme the “Lusitanian Brigades”—a vision that never materialised.

Looking back, I give thanks my grandfather never joined them. Had he done so, his name might now appear here among dozens, hundreds, thousands of the dead—men who, like him, once believed it worth dying for a country not their own.

How many grandchildren will read these words with clenched hearts, shedding tears for grandfathers lost? Men who still lie in African jungles, swallowed by the humid earth that long ago claimed them—a land that buried their bones but could never bury their ghosts.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Rafael Baptista is a 24-year-old journalist from Portugal driven by an unwavering passion for storytelling.

Curious and determined, he has spent over four years specialising in Politics and Security, investigating the rise of the far right and clandestine foreign espionage in Portugal. Inspired by Ryszard Kapuściński, Martha Gellhorn and many others, he is constantly on the move in search of extraordinary stories that transcend time.

Rafael can be reached at rafael.baptista2000@gmail.com.