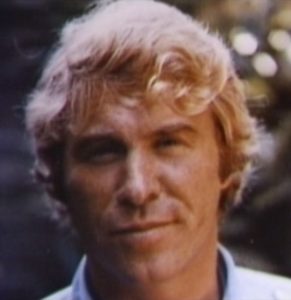

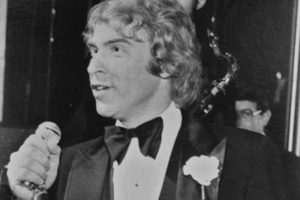

[Danny Casolaro supposedly committed suicide in 1991 while investigating intelligence activities involving the Inslaw/PROMIS affair he code-named “The Octopus.” Just before his death, Casolaro had a briefcase full of documents and notes. When his body was found, the briefcase was gone. The official version of events surrounding Casolaro’s death has been questioned since the beginning, but several recent revelations resulting from the release of government documents have undermined it.

Jack Colhoun explores the new evidence in this piece. As an investigative reporter and historian, Jack authored numerous CovertAction Information Bulletin / CovertAction Quarterly pieces in the past including: “Israeli Arms to the Contras” and “U.S. Supports Khmer Rouge.” He is also the author of Gangsterismo: The United States, Cuba, and the Mafia, 1933-1966.—Editors]

Did investigative reporter Danny Casolaro commit suicide as Special Counsel Nicholas Bua concluded in his 1993 report on the Inslaw Affair?[1] Or was Casolaro killed because he was digging too deeply into the U.S. intelligence community’s illegal use of Inslaw’s PROMIS software?[2] Records related to Casolaro and PROMIS released recently in response to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests call into question the official Washington narrative.

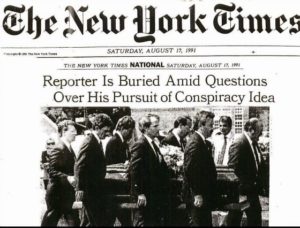

Casolaro was found dead, both wrists slashed multiple times, in the bathtub of his room at the Sheraton Inn in Martinsburg, West Virginia on August 10, 1991. Casolaro’s family, friends, and associates immediately raised the possibility of foul play, noting Casolaro had gone to Martinsburg to meet a “source.” On August 17, the New York Timesreported Dr. Anthony Casolaro was “very skeptical” that his brother had killed himself. Anthony Casolaro said “his brother had recently received numerous death threats and that none of his notes on the case were found with his body.”[3]

Special Counsel Bua acknowledged that Olga Moskos, an Arlington, Virginia neighbor, reported hearing a threat intended for Casolaro when she answered his ringing telephone. But Bua downplayed the significance of the threat Moskos described and, instead, concluded that Casolaro had killed himself. Bua explained, “There was ample reason to believe Casolaro had a motive to commit suicide.” Casolaro had been “unemployed for months,” “the balloon mortgage on his house” would be due soon, and his publisher would not give him an advance for the book he was writing on the PROMIS affair. Bua added, “several” of Casolaro’s friends questioned whether he had “invented” the death threats.

However, MuckRock writer Emma Best faults the Bua report for its marginalization of evidence of death threats that Casolaro received. Best points out Martinsburg Police notes of an interview with Moskos, which had been sealed by the Department of Justice, offer detailed evidence of death threats Casolaro received. “[Casolaro] received threatening calls. Olga took some. Guy was nasty. Kill him cut into pieces,” the police notes stated. “She advised that there were times when Danny would check his car before getting into it. That scared her.” The Martinsburg Police notes were released in response to a FOIA request Best filed.

Best is even more critical of Bua for dancing around the subject of Casolaro’s missing briefcase. Martinsburg Police did not find a briefcase in Casolaro’s room. Best writes, “According to the Bua Report, only one witness – a front desk employee at the hotel – thought they might have seen the briefcase.” Bua reasoned because “no other hotel employee recalled seeing Mr. Casolaro with a briefcase,” the desk clerk “was probably mistaken.”

According to Martinsburg Police Detective John McMillen’s hand-written notes, however, another witness, Barbara Bettinger, a Sheraton Inn maid, also reported seeing a briefcase. When Bettinger cleaned Casolaro’s room the day before his death, she saw a “briefcase on [the] dresser, open with papers sticking out of it.” Bettinger added, “[H]e acted real nervous and kept looking behind him when he was going down the hall toward the elevators.”[4]

The day Bettinger saw a briefcase in Casolaro’s room, August 9, was the same day William Turner, a former Hughes Aircraft employee, said he delivered “two packets of documents” to Casolaro in Martinsburg. Turner had been holding the documents in safe keeping for Casolaro. In a sworn statement, Turner explained Casolaro planned “to swap some info to his source for more information on Inslaw.” Turner stated the documents included “computer printouts and other documents [Casolaro had] received from un-named sources and from Alan Standorf and documents relating to the sale of modified PROMIS software . . . to Canada, Australia and Israel.” Casolaro told Turner that the meeting with a source in Martinsburg “had been arranged by Joseph Cuellar.”[5]

In the summer of 1991, Cuellar arranged a “chance encounter” with Casolaro at the Sign of the Whale Bar in Arlington, where Casolaro was known to hang out. Cuellar introduced himself to Casolaro as a major in the Army Special Forces who had just returned from the Desert Storm intervention in Iraq. Casolaro told Inslaw founder Bill Hamilton that Cuellar asked him what he did for a living. “Danny answered that he was researching a book on the Inslaw affair,” Hamilton recalled in an interview. “Cuellar responded that he knew all about the Inslaw affair because Peter Videnieks was one of his closest friends.” Casolaro told Hamilton that he had several other meetings with Cuellar. Videnieks was the Department of Justice contracting officer for PROMIS in the early 1980s.

In 1992, Hamilton began receiving information from a never-identified U.S. intelligence source through a third party, a retired Army Criminal Investigation Division officer. “My intelligence source claimed that Danny was murdered by U.S. Army Special Forces Intelligence Major Joseph Cuellar in the course of a covert intelligence operation,” Hamilton stated. “The objective of the operation was to recover every copy of computer printouts from a Defense Intelligence Agency PROMIS-based domestic surveillance database system called Main Core, acquired through the assistance of National Security Agency employee Alan Standorf.” Standorf was found beaten to death in the back seat of his car in a parking lot at Washington National Airport in January 1991.

Hamilton wonders whether Cuellar was the man an unnamed Sheraton Inn maid told the Martinsburg Police she saw leaving Casolaro’s room the morning of his death on August 10. The mystery man was mentioned in a meeting between Bill and Nancy Hamilton and Inslaw’s attorneys with Assistant U.S. Attorney Stephen Zipperstein and FBI Special Agent Scott Erskine in March 1994. Charles Work, an attorney for Inslaw, followed up on the subject in a March 14, 1994 letter to Assistant Associate Attorney General John C. Dwyer.

“We regard as significant the confirmation from Special Agent Erskine during the meeting that a maid at the Sheraton Inn in Martinsburg, West Virginia, had seen a man leave Mr. Casolaro’s hotel room the . . . morning of the death,” Work wrote. “According to Special Agent Erskine, the local police took a statement from the hotel maid in which she gave an eyewitness description of the man she saw leaving the room . . . A male in his 30’s, with an excellent sun tan, wearing a fashionable tee-shirt, dark slacks, and deck shoes.” Work referred to news reports that Casolaro had been waiting in the hotel bar for “a dark-skinned man.” Work asked, “Could that have been the same man whom the maid saw leaving Mr. Casolaro’s room . . . and whom she describes as having `an excellent sun tan’”?

Hamilton was taken aback by Assistant Associate Attorney General John Dwyer’s response. “I am troubled by the statement . . . regarding the `confirmation’ by Supervisory Special Agent Erskine of certain facts. In fact, neither Supervisory Special Agent Erskine nor Steve Zipperstein confirmed any such details,” Dwyer replied to Work on March 17, 1994. “To the extent you understood any part of our meeting as a confirmation of any facts . . . you are mistaken.” Hamilton shot back in an interview, “John Dwyer simply denied in writing what FBI Agent Scott Erskine admitted in front of Nancy and me and three Inslaw trial lawyers, two of whom were former assistant U.S. attorneys . . .”[6]

Meanwhile, other recently released records reveal there was skepticism elsewhere in the FBI about Bua’s conclusion that Casolaro had killed himself. An undated FBI report on the Inslaw Affair noted that Bureau’s Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) Task Force questioned whether Casolaro had committed suicide. The task force looked into Casolaro’s death because he had pursued leads that tied PROMIS to the BCCI banking scandal.

“[S]ome questions remain in my mind about the Casolaro death and his allegations,” the undated report stated. The unnamed writer said he asked fellow task force members off-the-record what they thought about Casolaro’s death. “At least half of them thought the matter should be further pursued and questioned the conclusion of a suicide.” The writer added, “[T]he level of doubt was especially significant, because it was clear to express those views risked one’s own judgment being called into question.”[7]

In the last few months of Danny Casolaro’s life, FBI Special Agent Thomas Gates took the unusual step of reaching out to Casolaro. Gates cautioned Casolaro to be careful about Robert Booth Nichols, whom the reporter had contacted because of his alleged links to PROMIS. Gates had interviewed Nichols as part of a separate FBI investigation of organized crime figures. Gates learned that Nichols, who had threatened to kill him, had also threatened Casolaro. “Gates warned Casolaro to be careful in his dealings with Nichols,” an FBI report on BNL and Inslaw stated. “Gates had two or three telephonic contacts with Casolaro, the last of which occurred shortly before the writer’s death.”[8]

[1]Report of Special Counsel Nicholas J. Bua to the Attorney General of the United States Regarding the Allegations of Inslaw, Inc., March 1993.

[2]In 1988, a federal bankruptcy court ruled that the Department of Justice “took, converted, stole” a version of Inslaw’s case management PROMIS database through “trickery, fraud, and deceit” in a contrived contract modification dispute. Inslaw contends the Reagan Administration stole “PROMIS for [use in] covert intelligence projects.” Inslaw Memorandum, “The Inslaw Affair,” July 2011.

[3]‘Reporter Is Buried Amid Questions Over His Pursuit of Conspiracy Idea,” New York Times, August 17, 1991.

[4]Emma Best, “DOJ Ordered Police Notes Contradicting the Suicide Narrative for Danny Casolaro Be Sealed,” February 7, 2018 at MuckRock.com. See also Emma Best, “The Danny Casolaro Primer: 13 Reasons to Doubt the Official Narrative Surrounding his Death,” March 15, 2018, and Emma Best, “FBI File Casts Doubt on Bureau’s Investigation into the Suspicious Death of Journalist Danny Casolaro,” May 8, 2017 are at MuckRock.com.

[5]“To Whom It May Concern: Matters Concerning Inslaw and Danny Casolaro” by William R. Turner, March 15, 1994.

[6]Letter from Charles Work to Assistant Associate Attorney General John Dwyer, March 14, 1994; Letter from John Dwyer to Charles Work, March 17, 1994; Letter from Charles Work to John Dwyer, March 24, 1994.

[7]FBI Report, “Justice Department Special Prosecutor Contacts (BNL and Inslaw)”

[8]Ibid.; FBI Special Agent Thomas Gates’ sworn statement is included in House Judiciary Committee, The Inslaw Affair(Washington: Government Printing Office, 1992).

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jack Colhoun is an independent historian of the Cold War (University of Wisconsin, Madison, BA, 1968; York University , PhD, 1976), an investigative reporter and professional archival researcher.

Colhoun has written widely on U.S. foreign policy and covert intelligence operations. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, Toronto Star, The Nation, The Progressive, National Catholic Reporter, Covert Action Quarterly and CovertAction Magazine.

Colhoun’s Gangsterismo: The United States, Cuba, and the Mafia, 1933-1966 provides an extraordinary, and comprehensive, history of the clashing epic forces over several decades in Cuba. He chronicles the history of Cuba before and after the revolution, the role of the U.S. government, and the criminal networks known as the Mafia.

Colhoun was a longtime Washington bureau chief of the storied radical newsweekly The Guardian until it closed in 1992. During the Vietnam War, Colhoun, an anti-war Army lieutenant, was a leader of draft and military resisters exiled in Canada and an editor of the American exile magazine AMEX-Canada.

Colhoun can be reached at: JHColhoun@aol.com.

[…] stated the documents included “computer printouts and other documents [Casolaro had] received from un-named sources and from […]

Thank you I’m is brother in Richmond I was living with Danny at the time of is death my brother Danny asked me to move out several months Pryor I did ..

I came to Danny house the weekend of is death to get my radio I saw is books on the table a tall Indian man in the kitchen he says he was a repair man I was skeptical I took a call they hung up I left

I am also highly skeptical of West Virginia Deputy Chief Medical Officer James Frost’s conclusion that “the manner of” Casolaro’s death was “suicide.” Dr. Frost’s post-mortem report indicated “two large deep” wounds in Casolaro’s right wrist. “Both of these incised wounds extend deep into the subcutaneous soft tissue to tendons.” Frost notes multiple cuts to the left wrist: “In the deep tissues of the incised wounds there is a segment of severed tendons.” To me it seems like too many deep cuts to be suicide, but that was the official ruling.

As I recall the razor? used to slice his wrist made a slash so deep that the tendons were cut. If the tendons in both wrists were cut, how would he be able to pick up the razor to deeply cut the other wrist? What did the autopsy reveal?

He wouldn’t Abby that’s just it there’s a Netflix biography coming out later this year ..the truth will come out ms Abby