[This is the second in a series of dispatches from our correspondents located around the world. These short updates provide succinct summaries on developments of the Far-Right and relevant intelligence activities. In this first Berlin Dispatch, Ellen Rivera provides a general overview of the country’s political landscape with a special look at the upcoming parliamentary election in 2021 and the possible coalition scenarios in a post-Merkel Germany.—Editors]

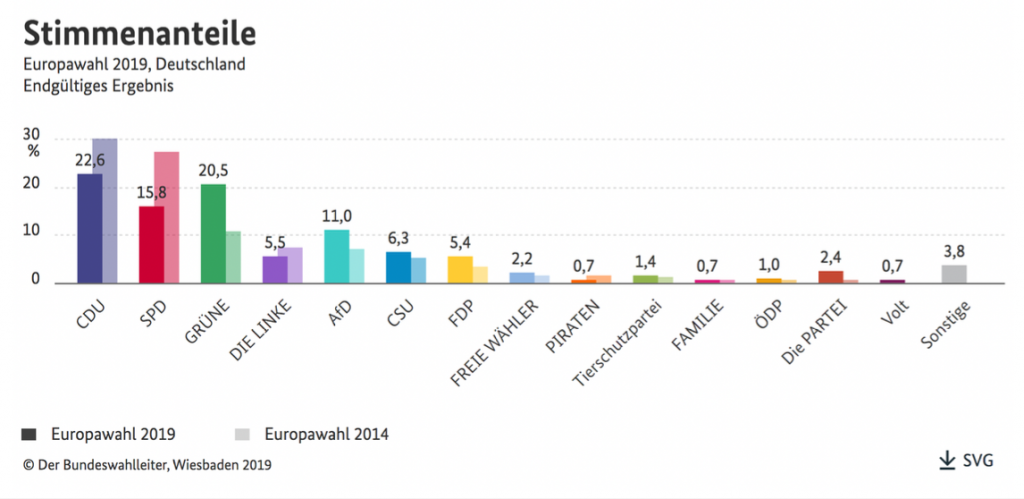

Many still see Germany as a beacon of stability in an increasingly polarized Europe, with the Christian Democratic chancellor Angela Merkel leading the country for 15 years in a row by now. But the façade of ostensible perdurability is crumbling quickly as the country currently experiences rather drastic shifts in its political power structure, which were already looming in the 2017 German federal election, but became glaringly evident in the 2019 European elections. These include:

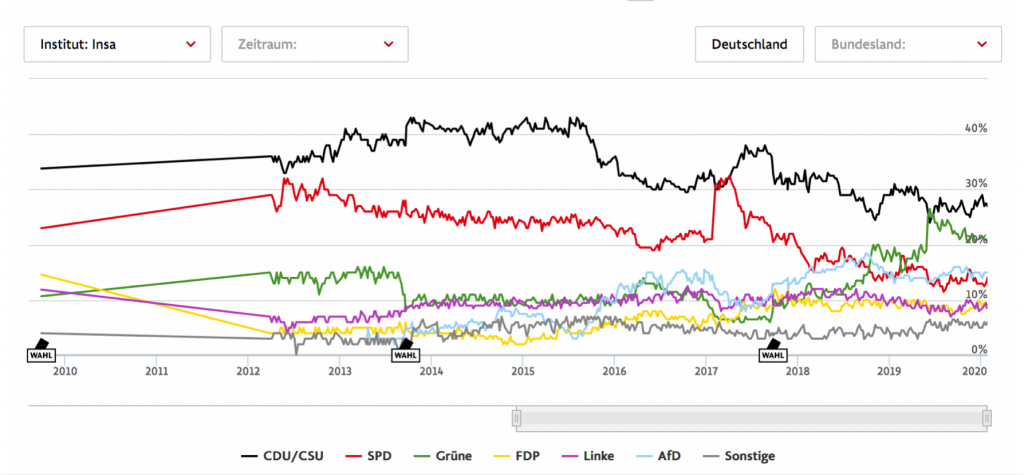

- A continued plunge in popularity of the two center parties, the Christian and the Social Democrats, which for a large part of the past two decades have shared the ruling power in a governmental coalition;

- An almost stellar rise of the Green Party ever since the global protests against climate change gained momentum, making it the second biggest party after the Christian Democrats;

- A continuing rise of the far-right party Alternative for Germany which, since its founding in 2013, managed to gain 15% of the national votes;

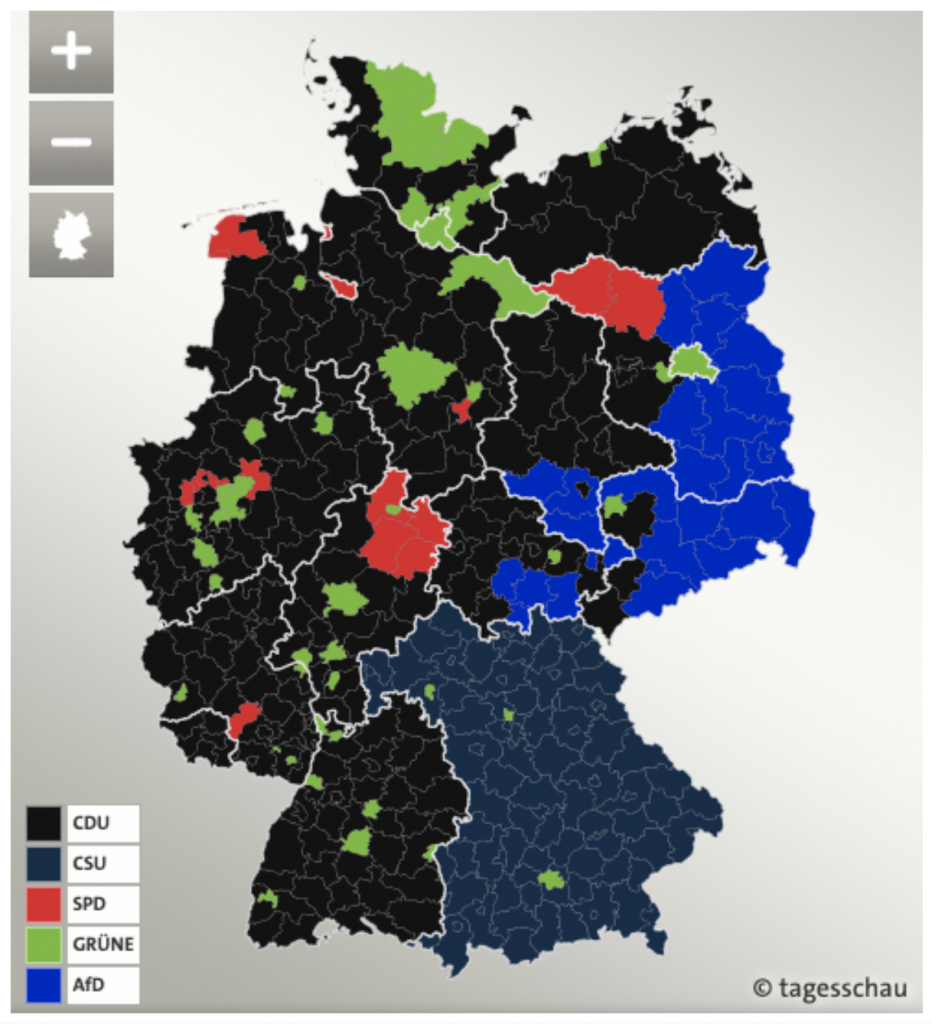

- A growing division between Eastern and Western German voting behavior, with major successes of the far-right AfD in Eastern Germany, and the Green Party in Western Germany;

- A growing division between younger and older demographics when it comes to party preferences, with a majority of voters under 30 turning their backs to most of the established parties.

While having a closer look at these major trends in German politics, this article aims to provide a general overview of the country’s political landscape. Furthermore, with regard to the upcoming parliamentary election in 2021, it will provide an outlook on possible coalition scenarios, which may follow the tenure of Merkel, who has announced that she will not run for chancellorship in the forthcoming term.

The Demise of the “Grand Coalition”

Germany has a multi-party system usually consisting of approximately six parties surpassing the five percent hurdle, covering the spectrum from the left to the far-right. Since no party alone could reach an absolute majority in the last several decades, coalitions had to be formed in order to obtain a majority in the parliament (Bundestag).

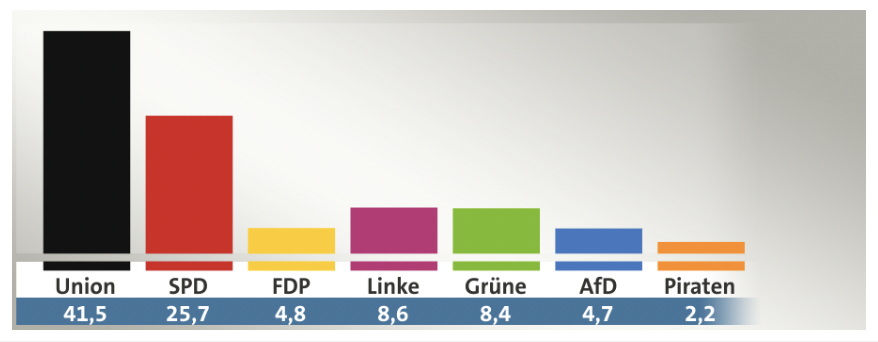

For the larger part of the past 20 years this has resulted in the formation of a so-called “grand coalition,” i.e., a coalition of the two biggest parties, hitherto the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). This version of the grand coalition has been in place from 2005 to 2009 and again since 2013.

Germany’s primary conservative rock, the CDU/CSU, whose double name is a result of a union of the West-German CDU and Bavaria’s even more conservative CSU, has since the immediate postwar period been the most powerful party in Germany, known for its iron course when it comes to facilitating capital interests.

The SPD, originally coming out of the 2nd International with its reformist agenda, had been historically the country’s most important anticapitalist party. But bargaining for power, it has put aside most of its former left-wing values, and especially in coalition with the CDU, kept on moving to the right.

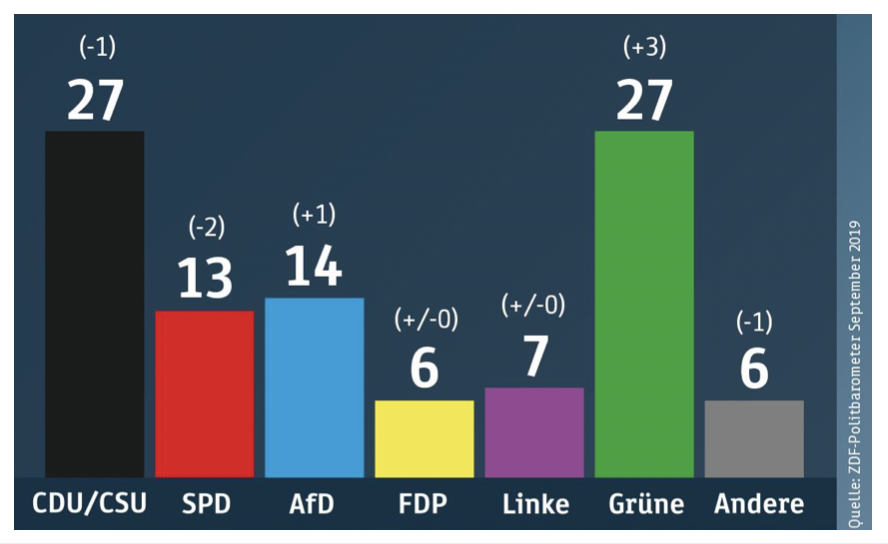

In the past, the two parties combined held more than 60% of the national votes, a relatively comfortable majority but, following the 2017 Bundestag election, started to experience considerable losses. According to recent polls, voter support has shrunk to merely 40%, indicating that the grand coalition may have reached its expiration date. The CDU/CSU has lost more than one-fourth of its voter base since the 2013 Bundestag election, currently holding an estimated 27% of the national votes. The SPD was hit even harder, having lost around one-third of its voter base since the last federal election. It is currently polling less than 15%.

While the rise of the AfD and the Green party has been emphasized as a major factor in the decline of both coalition parties, their surge seems an effect, rather than a cause, of a deeper dissatisfaction with center politics altogether. It appears that the center parties are finally suffering the consequences of the austerity course they embarked on decades ago, which slowly but surely has eroded the former welfare state and thrown every fifth German below the poverty line.

Like most other countries worldwide, Germany has been severely affected by capital flight and tax-dodging schemes in the past decades, pulling more and more wealth out of the country. The increasing strain on the public household led to the creation of large amounts of debt, which in turn were ever harder to pay down. But instead of tackling the causes, the powers-that-be took a series of severe austerity measures, as well as labor liberalization reforms in order to produce relief.

By the early 2000s, during the tenure of former SPD chancellor Gerhard Schröder, whose SPD/Green Party coalition (1998-2005) agreed on an all-encompassing labor market and social reform at the time, the cornerstones of future austerity politics were set. This so-called Agenda 2010 included major tax cuts, drastic cuts in pension and unemployment benefits, as well as cuts in the cost absorption for medical treatment, and kickstarted the thorough liberalization of the job market.

The belt of the public budget was again tightened following the financial crisis of 2008, this time by a coalition of the CDU/CSU and the neoliberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) that lasted from 2009-2013. As in the U.S., the burden of bailing out several German banks was put on the shoulders of taxpayers, including a “rescue package” with a volume of 500 billion euros. A cynical development, given that the culprits of the crisis were deleveraged, while the blameless had to carry the burden.

All in all, the past 20 years have been marked by a whole range of austerity measures that have more or less abolished the welfare state, for which ultimately changing coalitions between the CDU/CSU, SPD, FDP and the Green Party were responsible. The large-scale dissatisfaction with this course is certainly at the root of the declining support of both center parties in recent years, and also of new political developments that are currently shaking their established hold on power.

Rise of the Far-Right AfD

The growing disillusionment with center politics has clearly played into the hands of the surging far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD) which, since its inception in 2013 has managed to gain 15% of the national vote, and is currently in a head-to-head race with the SPD for the rank of the third biggest party.

The AfD’s sudden and swooping success caused a marked shift in the political climate of the country, its racist, post-factual, and antagonizing discourses resonating in parliament as well as in the media. Furthermore, the party’s xenophobic campaigns and constant attacks on the government’s immigration policies have been responsible for a considerable increase of right-wing extremist attacks against foreigners and politicians in recent years.

Voters from Eastern Germany have, in particular, turned away from the center parties toward the AfD, making it the biggest party in several federal states in that region. This is an especially disturbing development given that the Eastern German AfD is dominated by the most extreme faction of the party, called the “Wing” (Flügel), and many leading cadres have contacts with the right-wing extremist and neo-Nazi scene.

Political analysts consider the AfD’s swooping success in Eastern Germany largely as a protest vote against the established parties by a structurally disadvantaged constituency. Since the reunification, the former GDR territories have seen an unparalleled looting of state property, as well as the smashing and takeover of GDR industries by nonlocal investors. In the aftermath, particularly rural regions were left to their own devices, with state investments in infrastructural renewal failing to materialize. This led to a massive rural exodus to Western Germany and the metropolitan areas, leaving behind an aging population and the tristesse of abandonment and decay: a fertile ground for discontentment, political disillusionment, and, as it turned out, far-right rabble-rousers.

The AfD’s insidious rhetoric, combining racism, ostensible traditionalism, promises of law and order and financial relief, seems particularly to speak to male workers from the medium age range with mid-level education, which make up the largest part of AfD voters in Eastern Germany.[1] While among voters over 60 the center parties are still popular, among those under 30 there is a discernible polarization toward the AfD on the one hand and the Green party on the other.

But it would be more than naive to consider the AfD a popular protest party of the little man. A glance at the party’s program shows that it is driven primarily by financial interests, pledging inter alia for a tax reform that would considerably benefit people with high incomes. Pitching the working class against foreigners and immigrants perfectly serves the purpose of diverting the surging disenchantment with center politics, and is a clear indicator that the party is a creation of finance capital using fascism to enforce its interests.

This should ring all alarm bells, particularly in a country like Germany, which need not look far back in history to see how such a development is bound for disaster: In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 1929, Germany’s leading industrialists and bankers backed Adolf Hitler’s ascent to power.

Surge of the Green Party

Whereas recent elections in Eastern Germany have brought a considerable shift to the right, Western Germany is currently seeing a strong trend toward the Green Party. Compared to the 2017 Bundestag election, the Greens’ voter base has almost doubled, from 10.7% to 20.5%, making it the second biggest party after the CDU/CSU.

The sudden and steep rise of the 40-year-old party coincided with the global breakthrough of the climate movement in 2019. Certainly the environmental activism of Greta Thunberg, the “Fridays for Future” mass demonstrations, and groups such as Extinction Rebellion have fueled the societal debate to a large degree.

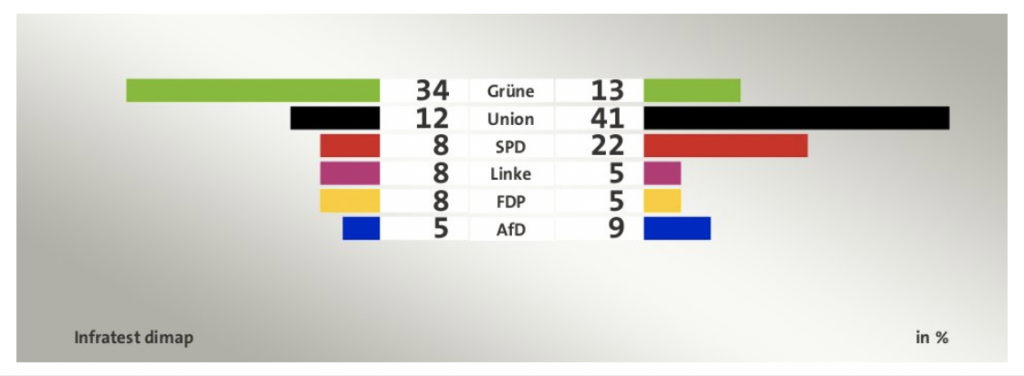

Two demographics in particular—young people and Western Germans from metropolitan areas—are behind the Greens’ recent increase in popularity. In the last European elections 33% of Germans under 30 voted for the party, making it by far the most popular choice in this age group.

Why a long-established bourgeois minority party would suddenly draw such an interest among younger and more progressive voters certainly seems paradoxical at first. Offering no critique of capitalism itself, but instead focusing on an environmental agenda, the Green Party is overall more conservative than the SPD. But with a general trend of redefining radicalism in terms of emotional militancy, as well as the surge of environmental discourses in the public debate, the Green Party has managed to create a more combative profile than the shopworn Social Democrats.

By and large, the surging Green wave has a marked influence on the discourses and campaigns of all other parties. While the coalition parties are currently trying to give themselves a more Green veneer in order to stop a further outflow of their core voter base, and bring apostates back into the fold, many center-right to far-right politicians are dismissing the trend as mere “climate hysteria.” With climate change denial inscribed in the party program, it is the AfD which is in the forefront of the opposition.[2] The party is currently networking with relevant interest groups on common strategies to tackle the threat of surging environmental discourses, which are diametrically opposing the party’s interests, as well as business interests at large.[3]

But it is not only the AfD which is decrying the green movement: Neoliberal and conservative politicians alike have joined the choir. Current CDU/CSU minister of defense, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, stated recently: “In case of doubt, the Green party does not opt for center politics, but for the left,”[4] a clear signal to fellow party members that changing their allegiance to the Greens equals leaving the conservative fold. Also, the neoliberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) is stirring up fears when it comes to a “red-green” alliance. FDP General Secretary Linda Teuteberg warned that citizens should not trust the Greens’ “threadbare promises of middle-class politics … because in the end they will not get a centrist course, the course of the future, but a left-wing alliance in a green dress.”[5]

Taking a look at the party program of the Greens, these fears seem greatly exaggerated, since far from a truly leftist outlook, the party’s environmental proposals merely foresee a shift to “Green capitalism.”[6] But that is certainly enough to pose a threat to a multitude of business interests that most of the established parties represent.

Future Coalitions

The rapid and rather drastic changes in the German political landscape make it hard to predict at this moment which coalition will succeed in the 2021 Bundestag election. However, due to the general surfeit with the grand coalition, future alliances may look very different than in the past two decades.

Since the Christian Democrats still have the largest voter base, a coalition with one or two other parties in the forthcoming legislative period is likely. And since it is generally easier to find a common line with one coalition partner rather than with two or more, an alliance with the Green Party seems not only numerically but also strategically conceivable. However, reaching a coalition agreement would not be an easy feat, given the Green Party’s demands for environmental reforms that would necessitate substantial changes in Germany’s industry and energy sectors. These touch upon the cornerstones of the CDU/CSU’s neoliberal politics, known for laying a protective hand over polluting industries and conventional agriculture.

Because at this point the combined votes for the CDU/CSU and the Green Party would only guarantee a narrow parliamentary majority, by the time of the next Bundestag election a third coalition partner could be necessary to obtain the required votes. In such a scenario, either the SPD or FDP would be considered as a coalition partner. However, any of the resulting combinations would make designing a coalition agreement difficult, given that some of the parties involved have fundamentally divergent political interests. In particular, the neoliberal FDP could collide with a future Green course.

Another coalition that is currently hotly debated concerns the CDU/CSU and the far-right AfD, now the third largest German party. Although the Christian Democrats have made it a party statute not to coalesce with the AfD at all costs, support for that commitment is slowly but surely crumbling. Since the AfD is now a strong political force, and the conservatives preponderantly refuse to coalesce with a party left of the SPD, the AfD appears in an ever more favorable light as a coalition partner.

The first voices among conservatives have already come forward to pledge for the hitherto taboo liaison. In this regard, the leadership of the CDU/CSU faction in the Saxony Anhalt state parliament, following the 2019 European elections, prepared a memorandum on a possible rapprochement between the two parties.[7] The report concludes that a majority of Germans would be conservatives at heart, and that CDU/CSU and AfD voters had generally similar goals. Conservatives, however, had alienated a large part of its voter base by not opposing “multicultural currents of left-wing parties and groups” with sufficient determination. In order for the CDU/CSU to become stronger again, it must “succeed in reconciling the social with the national.”[8]

For the AfD itself, a coalition with the Christian Democrats seems to be more a matter of time than a matter of principle. The party’s co-founder and former spokesman, Alexander Gauland, said in this regard: “They call us Nazis, fascists and right-wing terrorists … But we need to be wise and resilient. The day will come when a weakened CDU has only one option: us.”[9]

Although the German people will most likely be spared the horrors of a coalition between the conservatives and AfD in the upcoming term, political scientists are speculating that, if not during the next parliamentary election in 2021, latest in 2025 a coalition of the two parties could become a possibility.

There is a minimal chance that the CDU/CSU may altogether fail to find willing coalition partners, which would disqualify it from being part of a ruling government. Such a scenario would bring almost insurmountable difficulties for the other parties when it comes to forming a functioning coalition. A “red-red-green” coalition (SPD, Left Party, Green Party), the most progressive constellation imaginable in the current political situation, would not have enough seats in the Bundestag to achieve a governing majority. Given that these parties also categorically refuse to coalesce with the AfD, a numerical majority could only be achieved by way of including a fourth party in a coalition. This seems highly unlikely though, since the only potential coalition partner left would be the neoliberal FDP, which has fundamentally different political interests from the other parties in the constellation.

Conclusion

By and large, the 2021 Bundestag election will bring incisive changes to Germany’s political power structure, most likely ringing in the end of the long-established grand coalition of the Christian and Social Democrats. Furthermore, it will bring great challenges for the powers-that-be to form a governing coalition. The upcoming election will also see a major change in leadership, since longtime chancellor Angela Merkel will no longer run for office, and her protégé, the conservative Christian Democrat Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, has just thrown in the towel as party leader and, thus, as a potential chancellor candidate.

Although it is not certain who will fill the current power vacuum in the CDU/CSU, Friedrich Merz and Armin Laschet are presently identified as likely candidates. Armin Laschet, currently minister president of North Rhine-Westphalia, is a devout Catholic and known for his conservatism. Merz, a pro-business Atlanticist, is currently vice-president of the CDU’s economic council and, besides, serves as the supervisory board chairman of the German division of multibillion-dollar investment company BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager.[10]

Given the party’s notorious thwarting of any new policies other than those supporting the establishment, it seems extremely unlikely, no matter who makes the race, that the CDU/CSU will take a more progressive direction in the forthcoming legislature. However, with support for the Christian Democrats crumbling, and polls of the SPD plummeting, the way is paved for other parties to enter a ruling government.

The chances for the Green Party to enter a coalition are particularly high at this point, not least because a large part of the establishment still sees the Greens as a more attractive alliance partner than the far-right AfD. But with a noticeable shift to the right across the party landscape, a coalition with the AfD, and by extension most likely with the FDP, is no longer inconceivable.

These developments should be of ultimate concern to progressives, since far from a ray of hope, the Green Party seems more like a holding pattern for bourgeoises and leftists alike, which in case of a coalition with the CDU/CSU would most likely opt for a form of “eco-capitalism.” Such a project would be unlikely to free the country from its deadlock of a shrinking public household and growing austerity, but would very likely further burden taxpayers with the costs. The green movement, as timely and necessary as it may appear, cannot achieve its goals unless it becomes anti-capitalist at its core since what, if not capitalism, is at the root of most environmental problems?

Certainly, the same dilemma applies to the progressive parties, which will not find a way out of the current financial stranglehold unless returning to basic left discourses. A baby step has been reached when the SPD voted for a new party leadership in November 2019, comprised of the duo Saskia Esken and Norbert Walter-Borjans, which has called on the party to renew itself and to return to its former left-wing values. Walter-Borjans demanded that the SPD should “once again become the party of distributive justice,” and ensure that top-earners make an “appropriate contribution” to finance the common good again.[11] While a step in the right direction, emphasizing distributive measures over fundamental questions such as the power over the means of production is certainly indicative of the parties’ continuing center course. And despite the recent change of policy and leadership, it does not seem likely that the SPD will be able to recoup the votes that it has lost in recent years, last but not least because of its growing unpopularity among young voters.

The classic stronghold of the left, Die Linke, has also seen a recent leadership change, when long-standing head of the party, Sarah Wagenknecht, stepped down from her position in late 2019. Whether the new party leaders, Amira Mohamed Ali and Dietmar Bartsch, will bring an upswing to Die Linke—for years stagnating below the 10% mark—is hard to predict. It can be considered a positive development that the party has more voters under 30 than over 60, according to the results of the last European elections, and thus at least seems to have laid the foundation for its future. This young electorate, which is more concerned with gender equality and environmental protection than class struggle, will have to learn that their concerns, as important as they are, are of little overall political significance as long as capitalism can do its rampage.

[1] Annick Ehmann, Sascha Venohr and Vanessa Materla, “Wähler in Ostdeutschland: Männlich, Arbeiter, AfD-Wähler,” Zeit Online, September 2, 2019, https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2019-09/waehler-ostdeutschland-analyse-alter-geschlecht-beruf-schulabschluss-religion.

[2] “The trace gas CO2 is not a pollutant, but an indispensable prerequisite for all life. The statements of the IPCC that climate change is predominantly man-made are not scientifically proven.” See: “Programm zur Bundestagswahl,” Alternative für Deutschland, April 2017, https://www.afd.de/wahlprogramm/2/.

[3] Kate Connolly, “Germany’s AfD turns on Greta Thunberg as it embraces climate denial,” The Guardian, May 24, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/14/germanys-afd-attacks-greta-thunberg-as-it-embraces-climate-denial.

[4] “Rot-rot-grün: CDU-Vorsitzende Kramp-Karrenbauer warnt for den Grünen,” Berliner Morgenpost, June 9, 2019, https://www.morgenpost.de/politik/article226113817/CDU-Vorsitzende-Kramp-Karrenbauer-warnt-vor-den-Gruenen.html.

[5] “Rot-grün-rote Koalition: Erst Bremen, dann der Bund?” Tagesschau, ARD, June 6, 2019, https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/bremen-rot-rot-gruen-signal-bund-101.html.

[6] “Europas Versprechen erneuern. Europawahlprogramm 2019,” Die Grünen, April 3, 2019, https://cms.gruene.de/uploads/documents/B90GRUENE_Europawahlprogramm_2019_barrierefrei.pdf.

[7] “Sachsen-Anhalt: CDU-Politiker fordern Debatte über Koalition mit der AfD,” Zeit Online, June 20, 2019, https://www.zeit.de/politik/deutschland/2019-06/ulrich-thomas-sachsen-anhalt-cdu-afd-koalition.

[8] Zeit Online, “CDU-Politiker fordern Debatte.”

[9] “German far-right AfD party elects new leader backed by radical wing,” Euronews, January 12, 2019, https://www.euronews.com/2019/12/01/german-far-right-afd-party-elects-new-leader-backed-by-radical-wing.

[10] “Persönliche Erklärung zum Aufsichtsratsvorsitz von BlackRock,” Friedrich Merz, February 5, 2020, https://www.friedrich-merz.de/persoenliche-erklaerung-zum-aufsichtsratsvorsitz-von-blackrock/.

[11] “SPD wählt Doppelspitze und stellt neue Forderungen an die Union,” AFP, December 6, 2019, https://de.nachrichten.yahoo.com/spd-startet-spannung-erwarteten-parteitag-berlin-091756132.html.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Ellen Rivera is an independent researcher who specializes in the post-war German far right, with a particular focus on post-war anti-communist organizations. In the framework of her research provided for the George Washington University’s Institute of European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies (IERES), she has been studying the current links between proponents of the German and the Russian far right, mostly by means of extensive social network analyses and media monitoring.

Toller Artikel. Vielen Dank.

My partner and I absolutely loove your blog and find a lot of

your post’s to be precisely what I’m ooking for.

Does one offer guest writers to writte content too suit your needs?

I wouldn’t mind writing a post or elaborating on most of the subjects

you write with regards to here. Again, wesome

blog!