The Trial of the Chicago Seven, made by celebrated director Aaron Sorkin, has attracted the most attention of this fall’s double-feature look-back on Left-wing manifestations against the war. But The Boys Who Said NO!, produced by veterans of the war and opposition to the draft, provides some context for the events in Chicago that led to the trial. Albeit both document the distinction between liberal and radical challenges to the draft.

The Boys Who Said NO! lasers-in on one of the most divisive issues Americans faced during the war in Vietnam, an issue that was central to the outcome of the war itself: the conscription, or forced induction of thousands of young men for military service. By 1969 there were over 500,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam, a level that could never been achieved without the draft.

In turn, the resistance to the draft by the men it targeted twined with broader political and moral opposition to the war to fuel one of the largest social movements in American history. The film outlines the history of the war, gives us the details of the laws that enabled the draft, situates the biographies of draft resistors in the political culture of the times, and develops the story of divisions that set radicals and liberals apart by the end of the war.

The Trial of the Chicago Seven picks up on tensions within the antiwar movement that had become explosive by 1968. Heavy handed police tactics against war protesters and antidraft activists tested the principles and practices of nonviolent civil disobedience adhered to by the movement.

However, the liberal-radical divide over resistance to the war and the draft described by Boys evolved into a challenge to the legitimacy of the government itself and demands for change at its highest levels.

The Chicago Seven recounts the path of that evolution leading to the 1968 Democratic Party National Convention in Chicago where activists from around the nation gathered to support an agenda for peace in Vietnam in the upcoming presidential campaign. The movement’s bid for permits to protest was thwarted by city officials, their rallies were met with police violence, and its leaders were arrested. The trial that followed, recalled by historians as one of the great trials of the twentieth century, is the dramatic subject of the film.

Boys and Chicago Seven both ended with nods to the 2020 Presidential campaigns of Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Joe Biden as opportunities for considering the films’ contemporary relevance. Biden’s narrow victory, accompanied by down-ballot losses for other liberal democrats have party moderates castigating the Bernie Sanders-Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez wing for having scared away mainstream voters with the stridency of their health care, environmental, and police reform platforms. As this tension plays out, we would do well to keep the films reviewed here in the discussion.

The Boys Who Said NO!

As developed by Michael S. Foley in his 2003 book Confronting the War Machine: Draft Resistance During the Vietnam War, war resisters most commonly took advantage of legal loopholes that allowed exemption from the draft on religious grounds (conscientious objection), physical limitations (bone spurs) or medical conditions (high blood pressure), and deferments for college and occupational pursuits.[1]

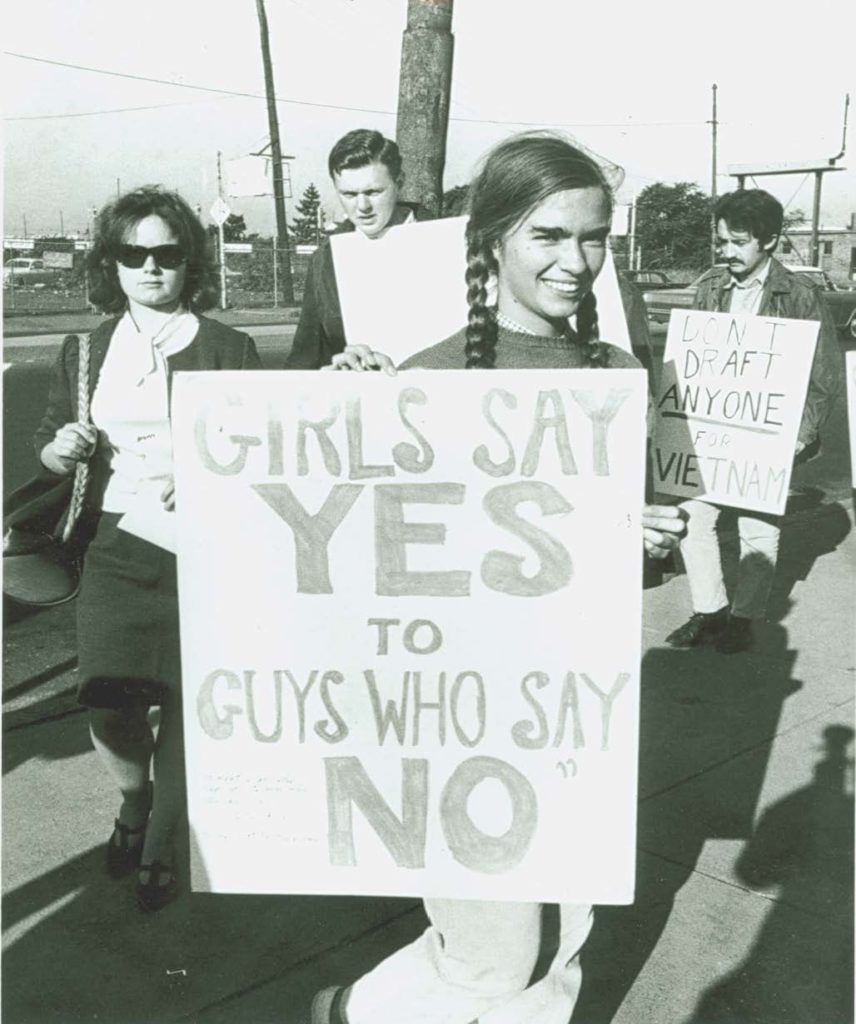

Foley classifies these as liberal tactics because they essentially played within the established legal structure, leaving the institutional legitimacy of the draft itself unchallenged and unchanged. Radicals like Foley, on the other hand, refused to even register for the draft, tearing up their draft cards and declining opportunities to stay out of the military offered by the law. The point was to stop the war, activist Tod Friend tells us, “not to save my ass.”

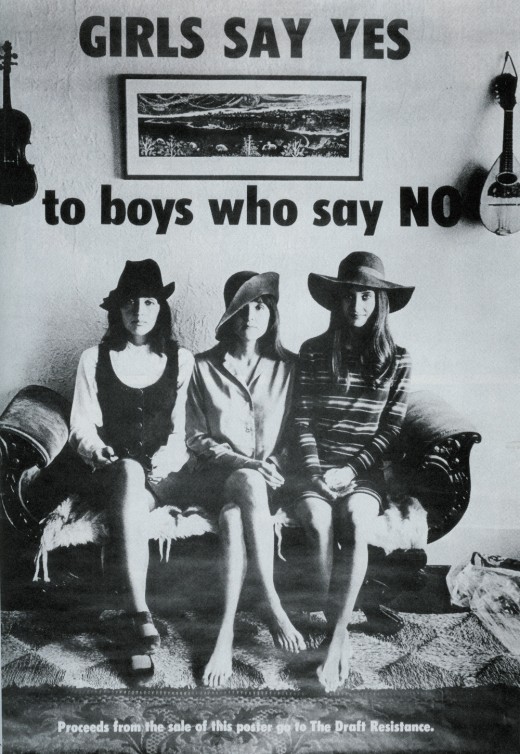

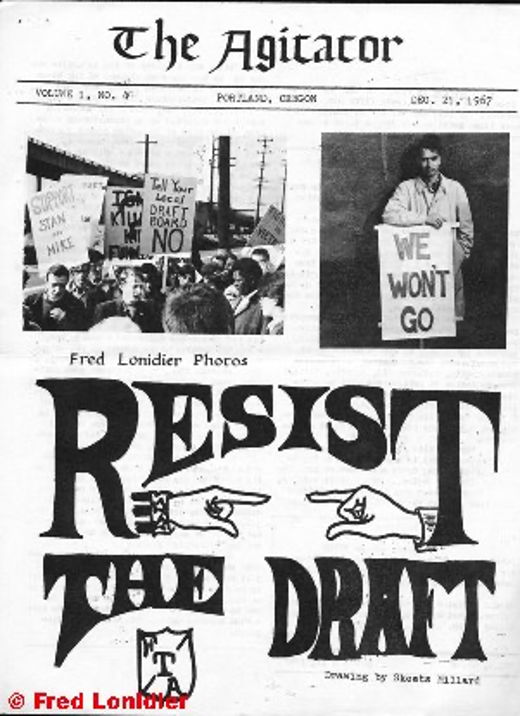

In 1967, the radicals founded a network, The Resistance, that set them more formally apart from the liberals who were publicly disparaged as draft evaders and draft dodgers. The Resistance included Bruce Dancis and David Harris, both of whom did prison time for noncompliance with the draft—hardly evading or dodging anything.[2]

Featured in the film, their stories, mixed with others, comprise a narrative of personal integrity and courage that will check off the role-model function that today’s viewers like to see in sixties-themed films. “I get courage by watching other people doing courageous things,” singer Joan Baez tells us, a purpose served, in turn, by the presence of her own story in the film.

Segments of The Boys pay tribute to the Civil Rights Movement for jump-starting the activism of northern white students like Harris who went to Mississippi in 1964 to register Black voters. While there, he witnessed a 70-year-old Black woman repeatedly defy denials to her right to vote. Her persistence and eventual success emboldened Harris to defy the draft.

But the film leaves untouched another dimension of the sixties-era draft story, one that magnifies the impact of The Resistance. By 1969, we are told, 200,000 draft-related cases had been sent to the Department of Justice; beyond The Resistance itself, the boldness of its actions were raising the consciousness of tens of thousands of other men facing the draft.

Meanwhile, the military was increasing its demands for manpower to meet the challenges posed by the 1968 Tet Offensive in Viet Nam. When draft boards had to go deeper into the pool of age-eligible men and reached those having been previously deferred for college and careers, they got people like me—older, college-educated, with previous exposure to the antiwar and countercultures.[3] It was this cohort of draftees—I dubbed it the Westmoreland Cohort for General William Westmoreland, the commander of U.S. forces in Viet Nam who had requested the troop buildup—which spearheaded the in-service G.I. movement, hamstrung combat operations and hastened the end of the war.[4]

The closing minutes of The Boys credential the film’s relevance for our current situation. One scene positions Resistance leader Harris in conversation with Mark Rudd, a leader of a militant breakaway wing of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) known as the Weather Underground; Rudd spent seven years on the run for a Greenwich Village explosion that killed three of his comrades.

Ultraleftism led to factionalism that splintered SDS and prevented it from recruiting liberal Americans to the movement for radical change; by going too-far-left-too-quickly, SDS ended up pushing allies away rather than winning them over.

The Harris-Rudd tête-à-tête works as a cautionary tale for today’s movements. The lesson, they agree, is “Don’t alienate the masses.”[5]

The Trial of the Chicago Seven

The Chicago trial followed events surrounding the August 1968 Democratic Party National Convention where police attacked protesters assembled to oppose the Party’s impending nomination of Senator Hubert Humphrey as its candidate for president. Humphrey, thought the activists, was certain to continue the war. The trial began in late September 1969, with Rennie Davis, David Dellinger, John Froines, Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Bobby Seale, and Lee Weiner charged for conspiracy to cross state lines to incite a riot. During the trial, Seale, a leader of the Black Panther Party, was separated from the others after being bound and gagged in the courtroom for demanding to represent himself. Those scenes will be emotionally intense for viewers unaware of the trial’s history.

Representation vs. Narrative

The fictional nature of a historical drama like The Trial of the Chicago Seven invites questions about its accuracy and authenticity; Slate.com devoted a whole column to a fact-check. By casting a megastar like Sacha Baron Cohen, famous for his comedic character Ali G. to play Abbie Hoffman, Director Sorkin drew attention to the Chicago Seven’s characterizations of the defendants. Those who were closest to the Chicago events, have zeroed-in on those portrayals: Do the depictions of Hayden and Davis infantilize the movement? Was the real Tom Hayden less reformist than the one portrayed by Eddie Redmayne? How authentic is Baron Cohen’s Abbie Hoffman? Is Rennie Davis diminished by the look and style given him in the film?

Viewers with generational distance from the trial seem better able to assess its relevance for 2020. An October 23, 2020 webinar on the film, organized by The Vietnam Peace Commemoration Committee, featured a panel that included defendant Rennie Davis, Tom Hayden’s son Troy, Dave Dellinger’s daughters, and Aislinn Pulley, a leader of the Black Lives Matter movement and daughter of Andrew Pulley a leader of Vietnam veteran opposition to the war. The defendants’ offspring were generally more appreciative of the film and less interested in matters of representation.[6]

The preoccupations of movement veterans connected to the trial with the way the film casts the defendants is the depoliticizing effect of the director’s decision to put entertainment values over political narrative—bait that Left activists should not have taken. That they did, testifies to the power of popular culture to reduce political discourse to clichéd themes: in this case, that the trial itself, augmented with the outrageous treatment of Seale and the ham-handed meanness of Judge Julius Hoffman, exposed a proto-fascist core of American political culture.

The lesson derived from the film is that the Left opposition to the nomination of the liberal Democrat Hubert Humphry for president, which the 1968 demonstrations in Chicago were all about, was a mistake that opened the door for the election of the right-wing Richard Nixon—a more strident iteration of the message delivered by Boys.

Transposed to the 2020 campaign season, the message was that opposition to the Democratic Party’s Joe Biden campaign would hand Donald Trump another four years in the White House and provide a chance to consolidate a fascist agenda, a 1968 déjà vu.

In an April 2020 open letter in The Nation Magazine signed by some 80 former SDS leaders and members, the old New Left rebuked their younger counterparts for supporting Bernie Sanders: If Sanders stayed in the race, they warned, he might draw enough votes from Biden to cost him a win in the primary. In turn, a Sanders campaign against Trump in the general election would alienate the masses—the specter of 1968 lodged in the memory of the Chicago activists—and hand the election to Trump.[7]

But was that an apt reading of the 2020 landscape or, for that matter, the situation faced by the Left in 1968? Was Judge Julius Hoffman’s courtroom a microcosm of a nascent Hitlerianism outside? Or was Hoffman a one-off ego-maniacal buffoon better left in the dustbin of history than revived by Sorkin as a Trumpian premonition—which is how the Chicago Seven would have us see him?

Speculations about a fascistic Trumpian response to his loss to Biden are distractions from the more pressing issue of how the Left approaches the liberal center: as a hunting ground for allies or as the defensive perimeter for the Right that has to be breached before ruling class power can be engaged? Does the front-line of political combat run between Left and Rightwing forces or between Left and liberal activists both inside and outside the Democratic Party?

The dangers of Left isolation from the liberal center were made a staple in left-liberal culture in the decades between the sixties and today; Boys and The Chicago Seven, usefully, show us the events that put us on that path.

But philosopher Gabriel Rockhill, in an October 14, 2020, CounterPunch.com article, deepens our understanding of Leftwing anxiety about appearing too Left to the political mainstream. The apprehension derives, he says, from the century-old accusation that the failure of German communists to unite with liberalism in opposition to the Nazis opened the door to Hitler. In reality he says, fascism and liberalism are “partners in crime,” and it is liberal ideology and the failings of liberal policies that fascists exploit to move the masses. It’s a thought as pertinent to where we go in the Biden years as to how we got to where we are.

Might it be that a Biden win proves pyrrhic? Could it be that fear for supporting Sanders would “alienate the masses” and throw the election to Trump result in a Biden presidency that intensifies the very conditions that brought Trump to power in 2016?

Biden’s resume, after all, includes support for NAFTA and the war in Iraq; he was the point man for neo-liberal interventions abroad for the Obama administration and embarrassed himself with pro and con positions on fracking in the final weeks of the campaign. These are the very policies and behaviors that begat the discontents that Trump fed on.

The reelection of Trump was a frightening prospect, but the can kicked down the road by a Biden victory risks packing the can with still more explosive power. If we listen to pollsters after all, it is the liberalism of the costal elites that has alienated the masses and driven them into the Trump movement.

Biden will also leave undisturbed the wellspring of Trumpism that a one-time City-on-the-Hill-America, of myth and legend, was brought down by treasonous duplicity, an enemy inside-the-gates yet to be held accountable.[8]

The Trump campaign slogan to “Make America Great Again” is premised on the revanchist notion that it was the Sixties—the war in particular—that knocked America off its perch. It is a dangerous idea that resonates with a wide swath of Americans whose quality of life stalled after 1970 and fell through the floor with the double-barreled hits of the 2008 long recession and the Covid-19 pandemic. It is the loss of the war ruminating in the political psyche that nourishes the seeds of a nascent American fascism, not the wacky personalities of the Julius Hoffmans and Donald Trumps.

A Biden White House is more likely to extend the Democratic Party’s string of misadventures abroad than to end it, and hence perpetuate the search for scapegoating which has provided the fuel for today’s radical right.[9]

Viewed and discussed in the context of the Biden vs. Trump campaigns, Boys and the Chicago Seven elicit the harrumphed “what were we supposed to do, vote for neither Nixon nor Humphrey? Neither Trump nor Biden?

It’s the NOTA-TINA knot (None Of The Above vs. There Is No Alternative) that sociologist Michael Schwalbe wrote about in his 2015 book Rigging the Game: How Inequality is Reproduced in Everyday Life. TINA, he says, reifies the status quo, giving us a fait accompli that stifles our search for alternatives, other ways of achieving societal ends. In the political world, TINA excludes consideration of candidates who threaten established leaders.

In fact, NOTA is an alternative, a powerful weapon that too often goes unused. In the campaign season just completed, the Left could have threatened the Democratic Party during the primary season with staying home at election time if the leadership did not get behind the Sanders’ candidacy. And the Left could begin now to push for reforms that open paths for alternative views and use the midterm elections of 2022 to rehearse the NOTA tactics.

[1] Michael Stewart Foley, Confronting the War Machine: Draft Resistance During the Vietnam War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

[2] Bruce Dancis, Resister: A Story of Protest and Prison during the Vietnam War (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014).

[3] I said “yes” to the draft when the call came in April 1968; in August I watched on television in the barracks recreation room—the “day room” in the military jargon of the time—at Fort Hamilton, as the Chicago police went berserk on demonstrators. My experiences were well within the historical context set by the war in Viet Nam but they did not intersect with the draft and resistance to the war so much as run parallel and even in sequence with those developments.

[4] David Cortright’s Soldiers in Revolt (New York: Anchor, 1973) documents the G.I. movement. The 2006 film Sir! No Sir! brought the movement to the screen. See also Andrew Hunt’s The Turning: A History of Vietnam Veterans Against the War (New York: NYU Press, 1999). I wrote about the Westmoreland Cohort here: “The Contradictions of 1968: Drafted for War, The Westmoreland Cohort Opted for Peace” The American Historian, May 1968.

[5] Mark Rudd, Underground: My Life with SDS and The Weathermen Underground (New York: Harper, 2010).

[6] The webinar can be accessed here: https://tinyurl.com/Chi7webinar.

[7] https://www.thenation.com/article/activism/letter-new-left-biden/.

[8] Joe Biden was in, but not of the sixties. “ . . . when Mr. Biden and his friends from Syracuse University law school happened upon antiwar protesters at the chancellor’s office—the kind of Vietnam-era demonstration that galvanized so much of their generation—his group stepped past with disdain. They were going for pizza”: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/17/us/politics/joe-biden-college-1960s.html

[9] As Barack Obama’s Vice President, Biden was the president’s point-man for foreign affairs; an assessment of the Obama-Biden record on war and peace is an indicator of what a Biden presidency will look like. Jeremy Kuzmarov’s Obama’s Unending Wars: Fronting the Foreign Policy of The Permanent Warfare State (Clarity Press, 2019) is a must read for that purpose.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jerry Lembcke is the author of eight books, including The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam, CNN’s Tailwind: Inside Vietnam’s Last Great Myth, and Hanoi Jane: War, Sex, and Fantasies of Betrayal.

His opinion pieces have appeared in the New York Times, Boston Globe, San Francisco Chronicle, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. He has been a guest on several NPR programs including On the Media. He is presently Associate Professor Emeritus at Holy Cross College in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Distinguished Lecturer for the Organization of American Historians.

Thanks for this interesting piece. I was surprised, however, that the author noted that the descendants’ offspring were generally appreciative of the film. As evidence, he references an Oct. 23, 2020, webinar which I watched. Dave Dellinger’s daughters intensely disliked Sorkin’s film. One of them was enraged that Sorkin had invented a scene where Dellinger, a life long pacifist who served prison time during WW II for his opposition to war, punches a court officer. In my view, this is just one of the many serious fabrications Sorkin presents in the interest of presenting his neo liberal take on the Chicago Seven.