On April 6, 2022, Burkina Faso’s ex-President Blaise Compaoré was tried, convicted and sentenced in absentia to life imprisonment for murder.

It took 35 years for justice to catch up with him for murdering his revolutionary socialist predecessor, Thomas Sankara (the “Che Guevara of Africa”), in a 1987 right-wing military coup.

How long will justice take to catch up with the CIA and its French intelligence counterpart, the Direction générale de la sécurité extérieure (DGSE), for what appears to have been their part in masterminding or enabling the plot that overthrew and killed Sankara?

[This article continues CAM’s series on political assassinations.—Editors]

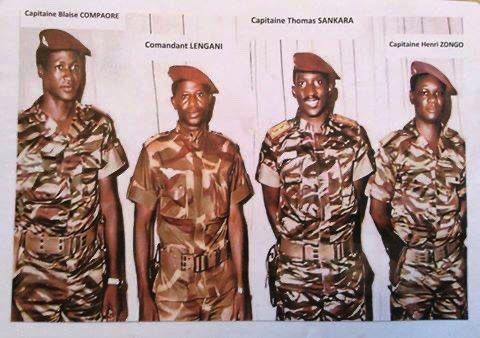

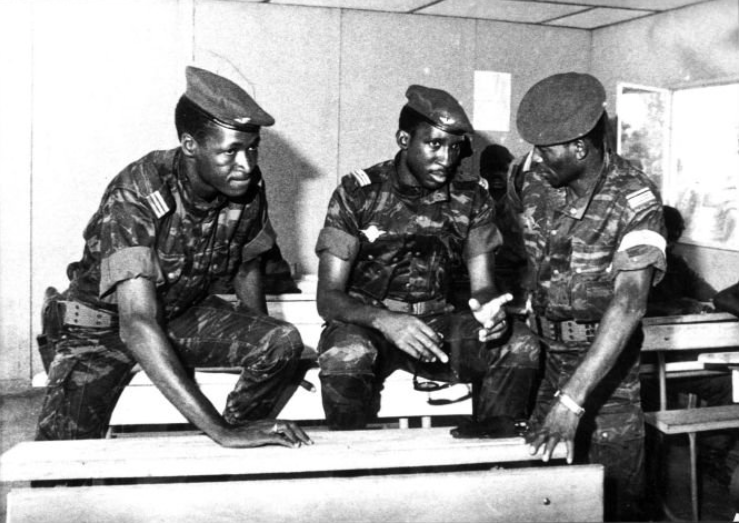

As young military officers in Burkina Faso during the 1970s and 1980s, Thomas Sankara and Blaise Compaoré were the best of friends. The two traveled the country playing in a musical band together and Sankara’s parents adopted Compaoré as his parents had died when he was young.

In 1983, Sankara and Compaoré launched a coup against Burkina Faso’s military regime by Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo. Sankara became president, and Compaoré his deputy, their bond remaining unshakeable.

But four years later, in an act of treachery fit for a Shakespearian tragedy, Compaoré and a group of commandos stormed a government building where Sankara was in a meeting and shot him at point-blank range.

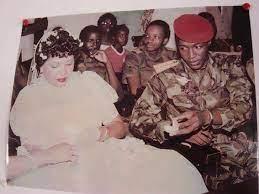

According to a witness who claimed to be in the room at the time, Compaoré—possibly at the urging of his wife Chantal, the daughter of Ivory Coast leader Houphouët Boigny—was the one to pull the trigger.

The witness, Momo Jiba, an aide to Liberian warlord Charles Taylor, stated, “I was right there when Thomas Sankara said ‘because you are my best friend, I call you my brother, and yet you assassinate me.’”

Upon hearing these words, Compaoré allegedly made an irritated gesture, said something to Sankara in French and then fired the first shot. If he had not done so, a man named Guengère, who later became Defense Minister, would have shot Sankara and become Burkina Faso’s next president.

Belated Conviction

On April 6, 2022, time and the law finally caught up with Compaoré, who was convicted in absentia in Ouagadougou for killing Sankara and sentenced to life imprisonment.

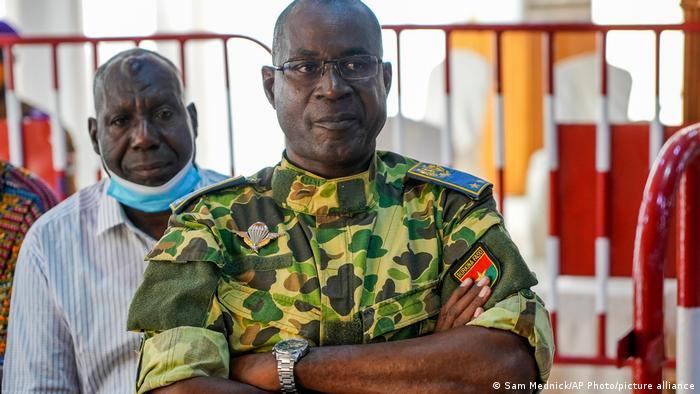

Hyacinthe Kafundo, Compaoré’s former head of security, and General Gilbert Diendéré, a former senior army commander with close ties to the U.S., were also convicted and given life sentences.

Five other people were found guilty of a range of offenses, including giving false evidence, bribing potential witnesses and complicity in undermining state security. Three were found not guilty, including the doctor accused of saying on Sankara’s death certificate that he died of natural causes.

The verdict was greeted with jubilation by Sankara’s supporters in the courtroom. Seated near the front, Sankara’s widow Mariam Sankara, who now lives in the south of France, said justice had finally been delivered. “The judges have done their jobs and I am satisfied. Of course, I wished the main suspects would be here before the judges,” she told the Associated Press. “It is not good that people kill other people and stop the process of development of a country without being punished.”

Throughout his 27-year rule from 1987 to 2014, Compaoré thwarted attempts to investigate the circumstances of Sankara’s death, including repeated calls for his remains to be exhumed (Sankara had been buried in a commoner’s grave), adding to speculation about Compaoré’s part in the murder.

Africa’s Che Guevara

Considered the “African Che Guevara,” Sankara was the rare revolutionary who was able to implement his ideals in power and to affect positive change.

He oversaw huge increases in health and education spending during his presidency, promoting reforestation, land redistribution, vaccinations and women’s rights.

Only 37 at the time of his death, he broke the power of Mossi chiefs who embodied the feudal and colonial past, and attempted to create a Burkina-Ghana economic union with a new currency that would end dependence on the French franc.[1]

Sankara additionally a) forged close relations with Cuba and other revolutionary states, b) repudiated an IMF structural adjustment program that would have forced cutbacks to social services, c) called for African debt refusal, and d) sought to resurrect the UN’s New International Economic Order (NIEO), a transnational governance initiative that sought to reform the global economy in order to redirect more benefits to the developing world.[2]

Burkina Faso was valued by outside powers because of its possession of rare earth minerals, including copper, zinc, limestone, manganese and phosphate and gold mining, which Sankara sought to keep under national control.

Compaoré, by contrast, privatized large sections of the Burkinabé mining industry, continuing the cycle of foreign economic domination and underdevelopment from which Sankara sought to free his country.

A December 1988 World Bank report tellingly praised the remarkably high standards of financial management in Burkina Faso during Sankara’s leadership but noted the growing prevalence of corruption since Compaoré had taken over.[3]

Described as “cold and calculating” with a “taste for luxury” that he shared with his wife, Compaoré was so close to the French that, when he was ousted from power in 2014, French troops evacuated him by helicopter to Ivory Coast, where he still lives.

Headquarters of U.S. Military and Surveillance Empire

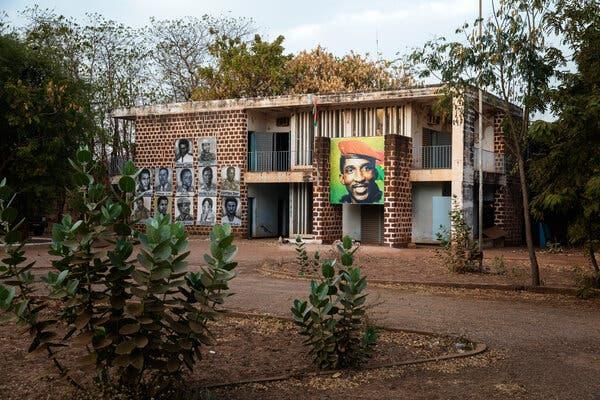

A generation after Sankara’s death, Burkina Faso has been transformed into a U.S. military outpost and headquarters of the U.S. surveillance empire in Western Africa.

In September 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle posed with Compaoré and his wife Chantal at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. At the time, several dozen U.S. military personnel and contractors were working in Burkina Faso.

The Obama administration provided more than $35 million in security assistance to Compaoré—even though Burkina Faso’s security forces had an atrocious human rights record.

AFRICOM during Compaoré’s rule was permitted to open a new surveillance base at Ouagadougou International Airport in a classified program known as Operation Creek Sand and a classified regional intelligence fusion center known as Aztec Archer was also established.

American Special Forces worked with the chief of Compaoré’s presidential guard, Gilbert Diendéré, his accomplice in Sankara’s assassination, and went into the field on patrols against Islamic insurgents embedded with local troops.[4]

In 2018 and 2019, the Trump administration pumped in $100 million in “security cooperation” funding—equal to about two-thirds of Burkina Faso’s 2016 defense budget—making it one of the largest recipients of U.S. security aid in West Africa.

This aid fueled greater instability with Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, who took part in at least half a dozen U.S. training exercises, seizing power in a coup in January 2022.

Burkina Faso today ranks only 144th out of 157 nations in quality of life indicators established by the World Bank, with 40% of the population living in poverty. Only about one-third of adults in Burkina Faso are literate, and fewer than 20% of residents have access to electricity.

“It’s Me They Are Looking For”

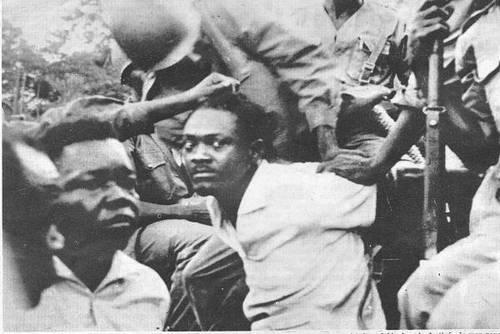

On the day of the killing, Sankara had just begun a meeting with members of his Cabinet when soldiers stormed in. According to the lone survivor, Halouna Traoré, Sankara declared, “It’s me they are looking for” and went outside to face his assassins, who killed him along with twelve of his associates.[5]

The findings of the autopsy—only made public in October 2015—corroborated that Sankara had been assassinated while holding up his arms—contrary to Compaoré’s claim that Sankara had shot first.

The subsequent radio broadcast announcing Sankara’s execution referred to him as a “traitor to the revolution” and “autocratic mystic” whose “high treason” was epitomized by his “personalization of power” and “use of mysticism to try to solve the problems of the masses.”[6]

The commandos that executed Sankara included Gilbert Diendéré, who would later be promoted to the rank of Knight of the Legion of Honor during a visit to France in May 2008 and briefly became head of state after mounting a coup in 2015.

Françafrique and the Removal of a “Troublesome Man”

During the 1960s, French President Charles de Gaulle (1959-1969) entrusted Jacques Foccart with the mission of holding West Africa under French influence even in an era of decolonization.

Nicknamed “Monsieur Afrique,” Foccart set up a network of contacts under de Gaulle and Georges Pompidou (1969-1974), which organized surveillance across the francophone African region and adopted covert actions and other “dirty tricks.”

This shadow network was termed “la Françafrique,” and was still operational when Sankara was killed. Though its records remain classified, we know that French agents were present at the time of Sankara’s assassination and had spoken about “destabilization efforts” with U.S. diplomats.[7]

France had withdrawn its financial aid prior to the coup in an effort to bankrupt Burkina Faso’s economy and provoke fissures in the revolutionary leadership,[8] and then destroyed wiretaps targeting Compaoré the day after the assassination.

On the day of the coup, Chantal Compaoré was in Paris under the company of Ambassador Barry Djibrina, her husband’s link to Foccart who obviously knew something was afoot.[9]

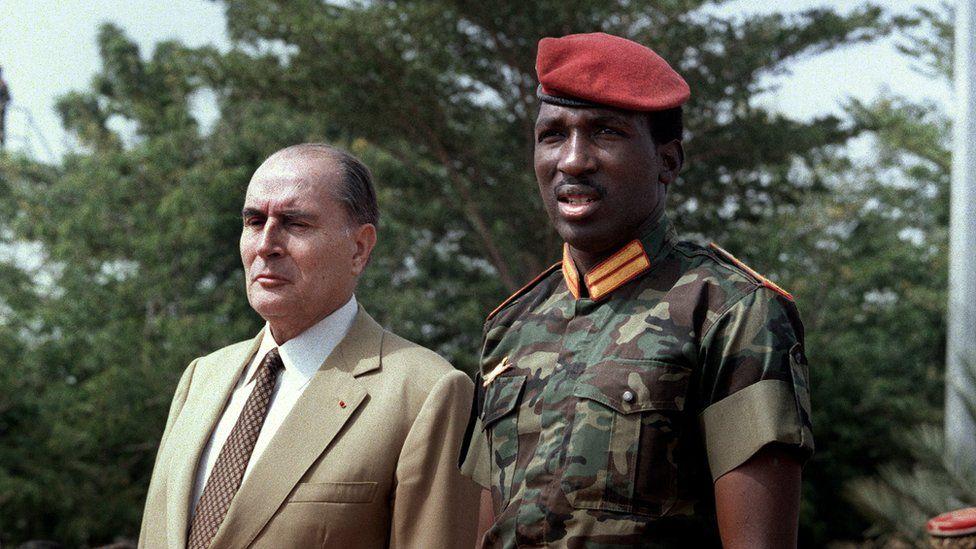

The French had wanted Sankara removed from the earliest days of his rule because he opposed the neo-colonial model that favored French interests in West Africa. At a reception during President François Mitterrand’s visit to Ouagadougou in 1986, Sankara lashed out at French policy in Africa, stating:

We cannot understand why bandits like Jonas Savimbi [Angolan warlord backed by the CIA], killers like Pieter Botha [Apartheid South Africa leader], have been authorized to travel to France, so beautiful and decent a country. They stained her with their hands and feet covered with blood. Those who allowed them to commit such actions will bear responsibility here and elsewhere in the world, now and forever!

These comments made Sankara a marked man. Mitterrand afterwards said, “I admire [Sankara’s] great qualities, but he is too forthright; in my opinion he goes too far,” adding “this is a somewhat troublesome man, President Sankara.”

This was exactly the view the Belgians had of another Pan-Africanist leader, Patrice Lumumba of Congo, who was assassinated soon after he publicly criticized the colonial system and suggested that the Belgians had not been benign overlords.

U.S. Seeks Regime Change Too

U.S. diplomats had a view of Sankara similar to Mitterand’s. One diplomat, John C. Baxter, was expelled from Burkina Faso for “subversive activities” that included “consorting with anti-government conspirators,” possibly while working under official cover for the CIA.[10]

Prior to the assassination, the military attaché at the U.S. embassy worked closely with his French counterpart in Ouagadougou. U.S. military training programs had provided access to “the very center of power,” with the U.S. embassy holding a seminar for senior military officers, including Compaoré. International Military Education and Training (IMET) program graduates were mostly pro-Compaoré, including Gilbert Diendéré’s brother Dominique.[11]

U.S. Ambassador Leonardo Neher (1984-1987), who had worked in Congo after Lumumba’s assassination, characterized Burkina Faso under Sankara as a “very radical, very troublesome country in West Africa,” whose leaders [led by Sankara] “had a Marxist vocabulary and were good friends with Qhaddafi’s [Libyan leader] and they were up on the stage everyplace in the world denouncing the U.S. and imperialism, and siding with Cuba, the Soviets, and with Nicaragua.”

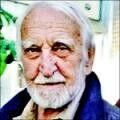

Herman Cohen, the former Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, recounted in a 1995 book that, “as a member of the American Executive, I accused Sankara of trying to destabilize the entire region of West Africa. Houphouët [Boigny] dismissed my concerns with the flippant remark, ‘Don’t worry, Sankara is just a boy. He will mature quickly.’ Since we were alone, I insisted that Sankara was hurting the image of the entire French community in West Africa and would eventually hurt Houphouët himself.”[12]

The latter was unacceptable as Boigny was long regarded as a bulwark against the spread of pan-African and socialist movements in Western Africa, a loyal friend to foreign capital and an ally in the Cold War.

After Compaoré seized power, the Reagan administration trained and funded the Burkinabé army in an attempt to stabilize his rule. This in spite of a reign of terror carried out by Compaoré, which included the arrest, imprisonment, torture and execution of Sankara family members and supporters.[13]

“Sankara Was a Socialist, So He Had to Go”

In 2009, Italian filmmaker Silvestro Montanaro produced a documentary, African Shadows, which implicated U.S. and French intelligence agencies in Sankara’s killing along with Compaoré.

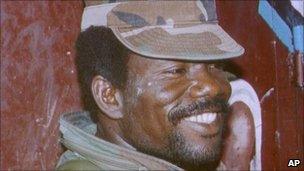

The film includes interviews with two close aides to Liberian warlord Charles Taylor, who had been recruited by the CIA to overthrow Liberian dictator Samuel K. Doe in the late 1980s.[14]

One of these aides, Momo Jiba, stated that his boss [Taylor] had told him to approach Sankara for help in taking power in Liberia in exchange for lucrative business opportunities.

When Sankara rejected the idea, Taylor met in Mauritania with a general named Guengère, later Burkina Faso’s Defense Minister, Blaise Compaoré, and Chad President Idriss Déby along with a white Frenchman who was probably part of Foccart’s network.

At the meeting it was decided that, for Taylor to be able to use Burkina Faso as a launching pad to wage war in Liberia, Sankara had to be eliminated and Compaoré would become president. All of this was part of America’s interest in controlling Burkina Faso, according to Jibo.

According to Cyril Allen, another of Taylor’s top aides, “the Americans and French sanctioned the plan to remove Sankara.”

Prince Yormie Johnson, another one-time Taylor associate, stated that the CIA had infiltrated the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) and convinced the NPFL leadership and Compaoré that Sankara had to be assassinated.

Cyril Allen [Source: frontpageafricaonline.com]

Charles Taylor [Source: wikipedia.org]

Prince Johnson [Source: bbc.com]

The United States wanted this, Allen affirmed, because “they were not happy with Sankara. He was talking of nationalizing his country’s resources to benefit his people. He was a socialist so he had to go.”[15]

-

Brian J. Peterson Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary in Cold War Africa (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2021), 257. Sankara also promoted close ties between Burkino Faso and China, accepting a $20 million interest free loan from China for agricultural development. ↑

-

See Ernest Harsch, Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary (Miami, OH: Ohio University Press, 2014.); Peterson, Thomas Sankara, 219. Sankara suggested that Africans did not have the means to pay back their debt, and that the loans had been issued with steep interest rates on the advice of Western financial experts who ultimately bore responsibility for the mushrooming of the debt. ↑

-

Unlike many African leaders of the time, Sankara himself lived austerely. At his death Sankara is reported to have left his $450 salary, a modest sedan car, four bikes, 3 guitars, a fridge and a broken freezer. ↑

-

Jeremy Kuzmarov, Obama’s Unending Wars: Fronting the Foreign Policy of the Permanent Warfare State (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2019), 104; Craig Whitlock, “U.S. Expands Secret Intelligence Operations in Africa,” The Washington Post, June 13, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/us-expands-secret-intelligence-operations-in-africa/2012/06/13/gJQAHyvAbV_story.html. ↑

-

Only Halouna Traoré survived to tell the story of the killing. Peterson, Thomas Sankara, 291. ↑

-

Elliott Skinner, “Sankara and the Burkinabe Revolution: Charisma and Power, Local and External Dimensions,” The Journal of Modern African Studies, 26, 3 (1988), 437. ↑

-

Though intent on minimizing foreign involvement in the assassination, Peterson points to the presence in Burkina Faso of a French military officer tied to the Foccart network—thought to be General Jeannou Lacaze (aka “The Sphinx”), Francois Mitterand’s Chef d’Etat-Major for the armed forces—in the months before the assassination. Peterson, Thomas Sankara, 230. ↑

-

Peterson, Thomas Sankara, 271. ↑

-

Peterson, Thomas Sankara, 285. ↑

-

Peterson, Thomas Sankara, 153. The CIA at the time was also involved in regime-change efforts in Ghana directed against Jerry Rawlings who was close to Sankara. President Ronald Reagan refused to meet with Sankara at the White House because a speech he gave before the UN General Assembly was considered to be too radical. Instead, Sankara visited Harlem where he was revered. Harsch, Thomas Sankara, 113, 114. ↑

-

Peterson, Thomas Sankara, 276. Some of the pro-Compaoré officers “expressed longing for the old days of corruption because they utilized this as a means of supplementing their low salaries.” ↑

-

See Herman J. Cohen, The Mind of the African Strongman: Conversations with Dictators, Statesmen, and Father Figures (Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, 2015); Peterson, Thomas Sankara, 273. ↑

-

See Peterson, Thomas Sankara, 294, 296. A resident of Ougadougou recounted in 2013 that, under the new post-Sankara order, “anyone who opposed Blaise was killed. Blaise’s men massacred people and traumatized the people, and we were afraid to speak out.” ↑

-

See Jeremy Kuzmarov, “How the CIA Helped Ruin Liberia,” CovertAction Magazine, July 30, 2021, https://covertactionmagazine.com/2021/07/30/how-the-cia-helped-ruin-liberia/. The CIA had helped Taylor—who had been accused of embezzlement by Doe when he was a finance minister—escape from a county jail in Massachusetts in 1985. ↑

-

Niels Hahn, Two Centuries of US Military Operations in Liberia: Challenges of Resistance and Compliance (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press, 2020), 121. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.

[…] CovertAction Magazine 29 April 2022 […]

[…] This Man Pulled the Trigger, But Did the CIA and DGSE Put the Idea in His Head and the Gun in His Ha… […]