So far the 2020s have been a very bad time for American democracy, with the January 6, 2021, riots, censorship on Twitter, Facebook and in the classrooms, rising anti-Russian fervor resulting from the conflict in Ukraine, COVID-19 lockdowns, declining newspapers and marginalization of anti-war voices.

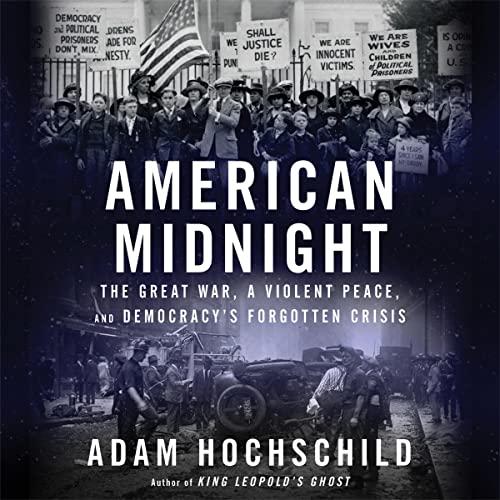

Still, as bleak as things are, they are not quite as bad as during World War I, as Adam Hochschild reminds us in his book, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (New York: Mariner Books, 2022).

Hochschild, a founder of Mother Jones magazine, has written eleven books, including such classics as King Leopold’s Ghost and To End All Wars (both finalists for the National Book Critics Circle Award), which, respectively, explored the sadism of Belgian colonialism in Central Africa and the folly of global leaders that provoked World War I.

American Midnight follows up the latter very well in detailing what he calls the “overlooked but startlingly resonant period between World War I and the Roaring Twenties, when the foundations of American democracy were threatened by war, pandemic and violence fueled by battles over race, immigration, and the rights of labor.”

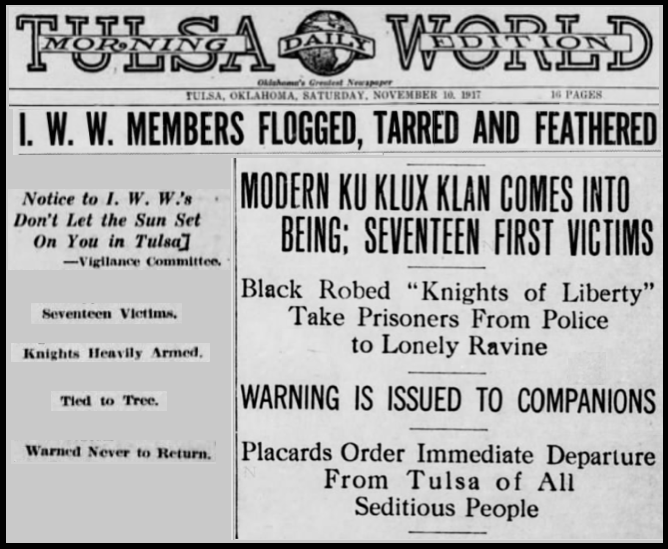

The book begins by spotlighting the experience of eleven members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) who had the audacity of trying to organize oil field workers near the rugged oil boom city of Tulsa, Oklahoma, just after the Great War had broken out.

The IWW was the country’s most militant union, which advocated for worker-controlled industry.

While playing cards one night at the IWW local headquarters, the men were arrested, charged and found guilty of vagrancy, and then taken to a railroad crossing where robed members of the Knights of Liberty tied their hands with rope, stripped them of their clothing, marched them at gunpoint and tied them to trees, whipped them until their backs bled and then brushed hot tar on their backs and chests.

The ringleader of the pogrom was thought to be city father W. Tate Brady—who also coordinated Tulsa’s infamous 1921 race massacre. He announced that he was carrying out the attack “in the name of the outraged women and children of Belgium [which Germany had invaded in starting World War I].”

The Knights of Liberty had the support of the Tulsa Daily World, the voice of the state’s oil industry, which published an editorial the afternoon of the attack stating: “The first step in the whipping of Germany is to strangle the I.W.W. Kill ’em, just as you would kill any other kind of a snake….It is no time to waste money on trials and continuances and things like that. All that is necessary is the evidence and a firing squad.”

Irrational Hysteria

The attacks on the IWW coincided with a period of war fervor—somewhat reminiscent of our own time—in which a Minnesota pastor was tarred and feathered because people overheard him praying in German with a dying woman.

In New York City, the Metropolitan Opera announced that it would cease performing works in German, foreshadowing its actions a century later when it vowed to stop engaging with artists or institutions supported by Russian President Vladimir Putin—the modern-day stand in for the German Kaiser.

On February 27, 2022, the Met’s General Manager, Peter Gelb, said in a video shared on Facebook, that “the Metropolitan Opera opens its heart to the victims of the unprovoked war in Ukraine and salutes the heroism of the Ukrainian people.”

But the war in Ukraine was not unprovoked, just like Germany’s invasion of Belgium, the triggering act in World War I that aroused so much opprobrium in its day, was not unprovoked.

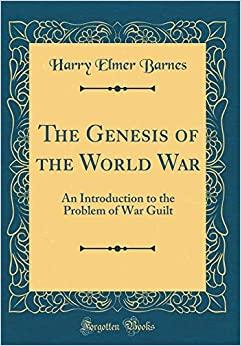

Harry Elmer Barnes detailed in his 1926 book, The Genesis of the World War: An Introduction to the Problem of War Guilt, how Germany was lured into invading Belgium in a trap set by Britain, Russia and France, which wanted to reclaim lost territory from the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War, and had encircled Germany militarily and was poised to invade it at any moment.

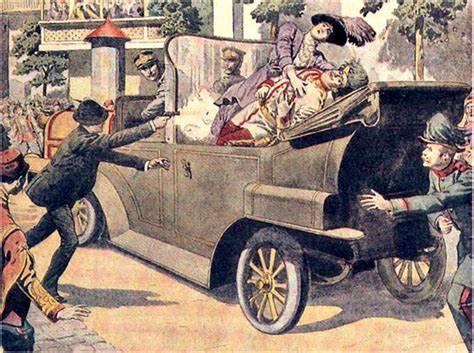

Czarist Russia also coordinated the assassination by a Serb nationalist of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand—another triggering act of World War I, which strengthened the Austro-Hungarian empire’s alliance with Germany against Russia (and France) who backed the Serbian drive for independence.[1]

A War for Democracy?

As a former professor and president at Princeton, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was a far greater orator and intellect than current American President Joe Biden, and a more gifted salesman for overseas military intervention.

On April 2, 1917, Wilson gave the speech of a lifetime announcing U.S. entry into the Great War, which violated his 1916 campaign pledge “he kept us out of war.” Emphasizing the perniciousness of German submarine warfare, Wilson ended his speech by proclaiming that: “There are, it may be, many months of fiery trial and sacrifice ahead of us…civilization itself seemed to be in the balance. But the right is more precious than peace…America is privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave her birth.”[2]

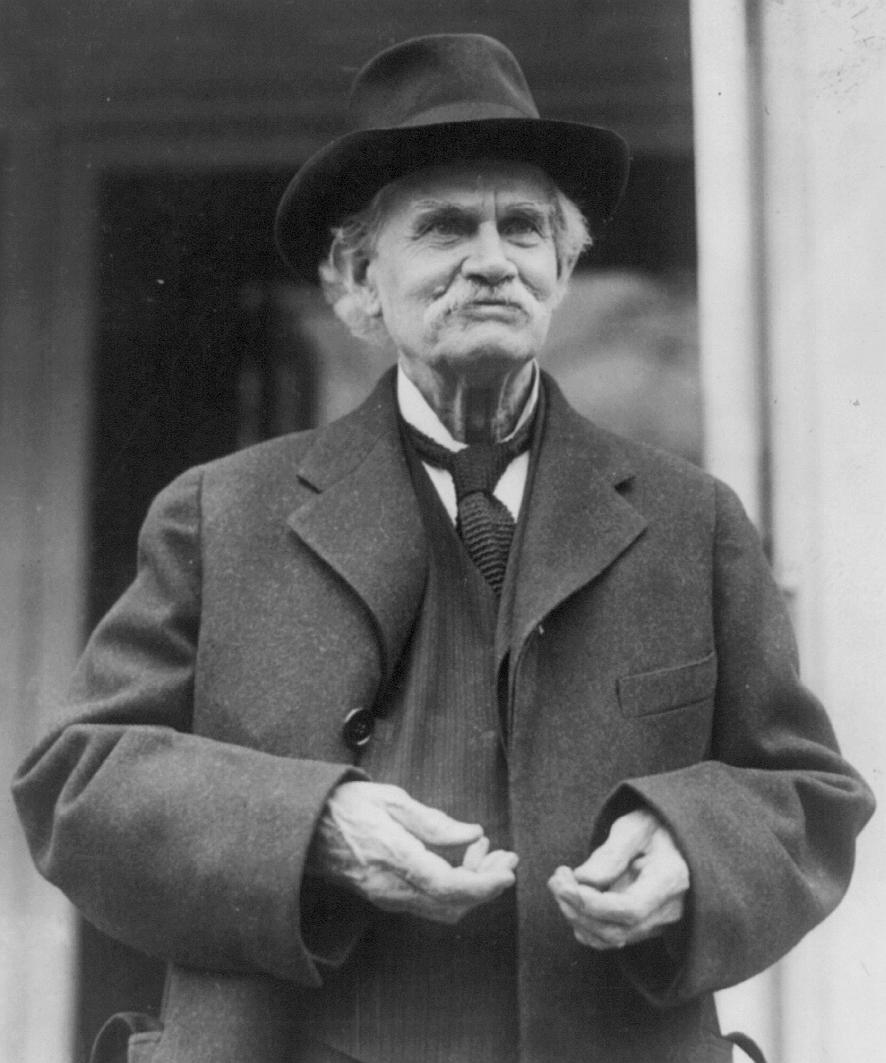

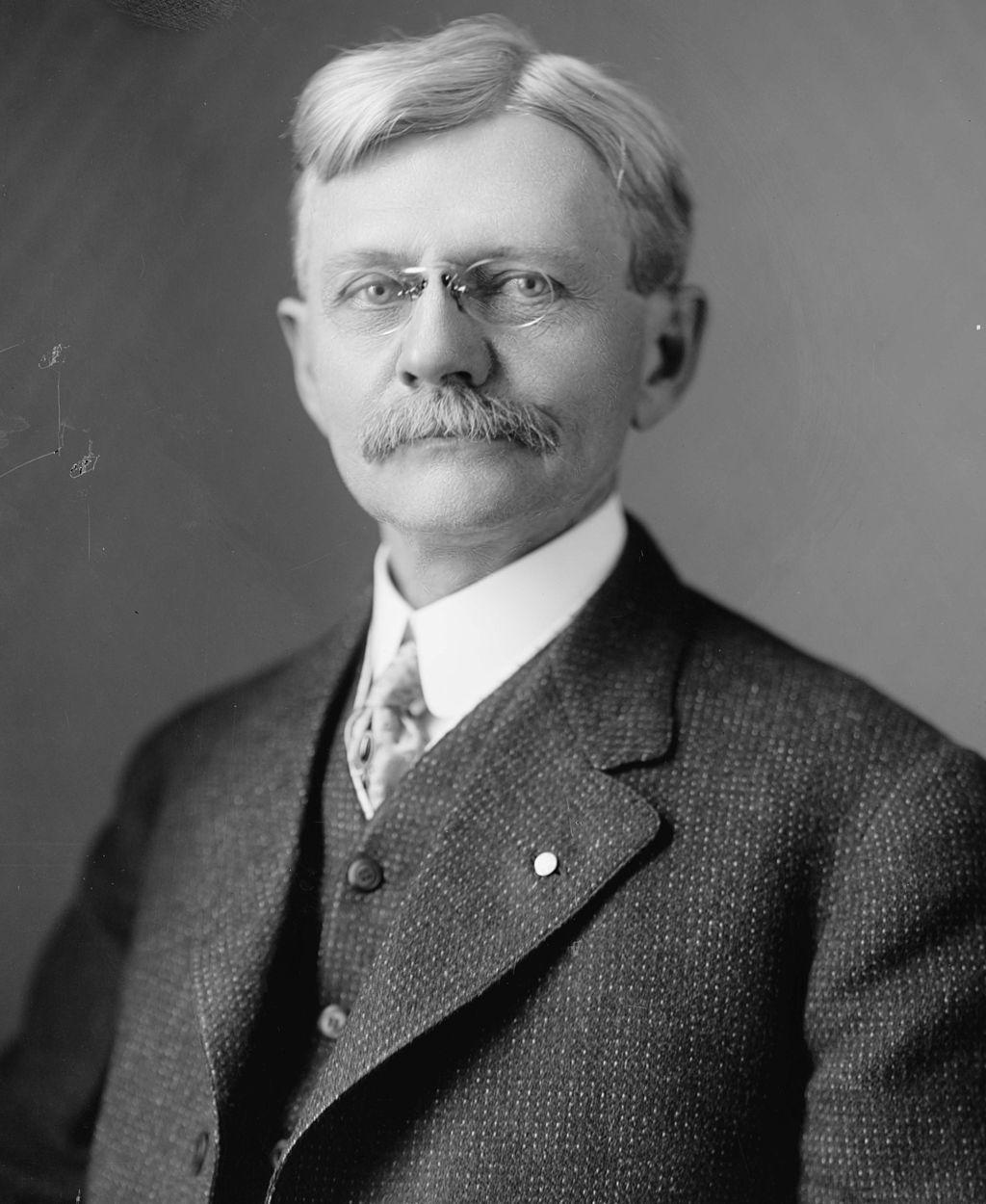

Wisconsin Senator Robert La Follette (R) was not among those who joined in the cheering.

In a three-hour Senate speech, he asked pointedly, if this was a “war for democracy [as Wilson had claimed], why was it that the President had not suggested that we make our support of Great Britain conditional on her granting home rule to Ireland, Egypt or India.”[3]

For this heresy, La Follette was attacked on the Senate floor by Mississippi Senator John Sharp Williams (D) as a “pro-German, pro-Vandal, and pretty nearly Pro-Goth.” Williams suggested that La Follette’s speech would have been better given “in the German Reichstag.”[4]

At his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin, La Follette was hanged in effigy, with all but two of the campus’s faculty members signing a petition denouncing him.

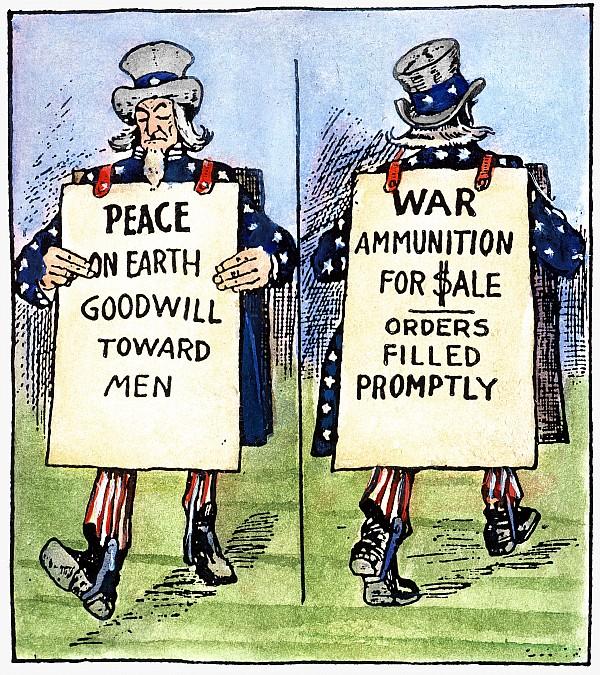

Merchants of Death

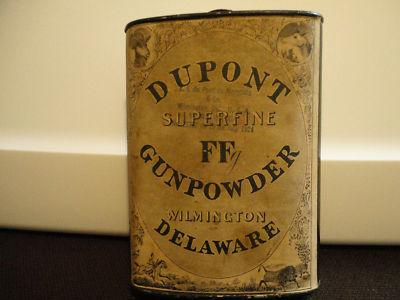

Whereas the Ukraine War has been good business for major defense contractors like Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, and Boeing, the Great War was a boon for DuPont, the manufacturer of gunpowder, which quadrupled its assets and increased the dividends it paid to stockholders by a factor of 16.

Bethlehem Steel’s stock price rose 17 times over during the Great War; paying shareholders a 200% profit margin, with many officials of the War Industries Board coming from the steel business.

The huge expansion of the military also created a demand for canned food for the troops, allowing four major meatpacking firms to increase their sales to 150% of the pre-war levels, while seeing their profits soar 400%.[5]

Father of American Military Intelligence

President Wilson’s declaration of war in 1917 was greeted enthusiastically by Colonel Ralph Van Deman, the “Father of American military intelligence,” who had developed a sophisticated information management system adopting use of indexed file cards to track Filipino insurgents opposed to the U.S. occupation of the Philippines.

After U.S. doughboys shipped out to France, Van Deman was directed by Secretary of War Newton Baker to set up a new army intelligence branch to spy on U.S. civilians who represented potential fifth columnists. Employing a staff of more than 1,200 people, including one agent in New York who was an early expert in the art of telephone tapping, this branch continued Van Deman’s work from the Philippines by compiling file cards on hundreds of Americans, many of whom were of left-wing persuasion.

Trouble In Bisbee

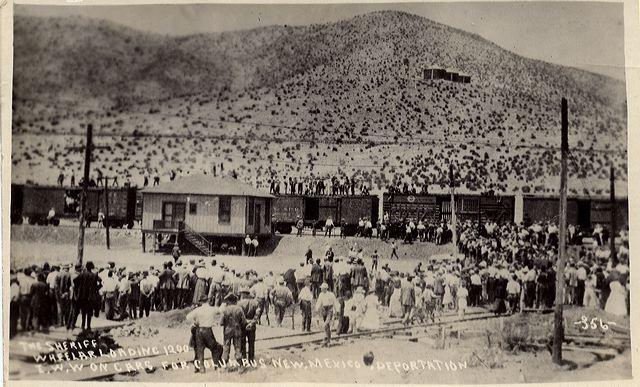

In June 1917, when miners working for Phelps, Dodge & Co. in Bisbee, Arizona, organized a strike to protest the absence of wage increases when company profits had soared because of rising demand for copper, Van Deman reported to his superiors that “enemy agents” were “endeavoring to stir up trouble in the mining camps.”

The local sheriff subsequently assembled a vigilante posse which shipped the miners in cattle cars into the desert where they were left in 112-degree heat.

President Wilson privately voiced his disapproval but did not nothing to punish the perpetrators or censure the company, whose owner, Cleveland Dodge, was Wilson’s old Princeton classmate and a key donor who had helped him gain the New Jersey governorship and presidency.

A Splendid Way of Getting Rid of Outlaw Leaders

The most draconian piece of legislation of the era was the Espionage Act, which was used then—as now—as a “club to smash left-wing forces of all kinds.”

Congressman Albert Johnson (R-WA), who hated the IWW as much as he did immigrants, told his fellow lawmakers that the bill would be a “splendid way of getting rid of these outlaw leaders. The IWW’s whole object is to breed hatred and treason.”[6]

A North Carolina senator, Lee Slater Overman (D), who ran a committee investigating German and bolshevik activities in the U.S. that was a forerunner to the McCarthy-era House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), declared that the Espionage Act was needed to prevent propaganda “urging Negroes to rise up against the white population.”[7]

The Espionage Act defined opposition to the war of almost any sort as criminal, with the penalties being draconian: a fine of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for more than twenty years, or both.[8] President Wilson wanted more still, inserting a clause that allowed censorship in newspapers.

A Free Soul in Jail

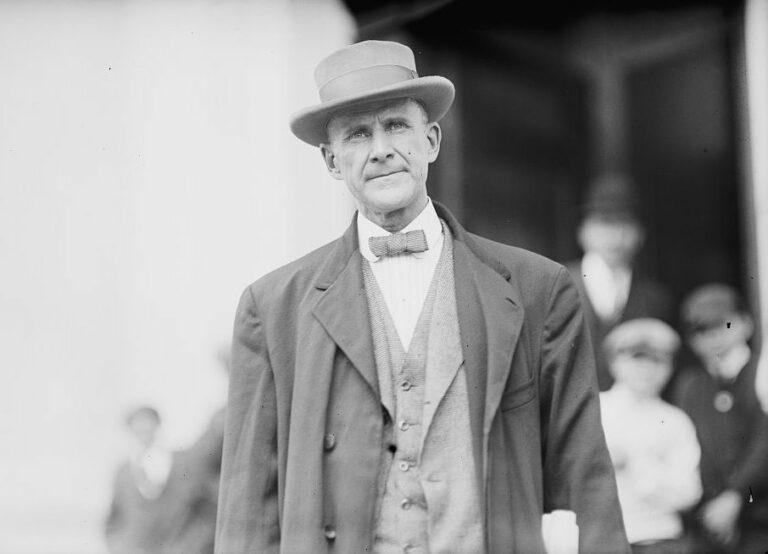

One of the most prominent people prosecuted under the Espionage Act was Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs. He was indicted under it after he gave a speech in Canton, Ohio, in which he declared “I would rather a thousand times be a free soul in jail than be a sycophant and coward in the streets.”[9]

The Worst Human Being to Serve As Postmaster General

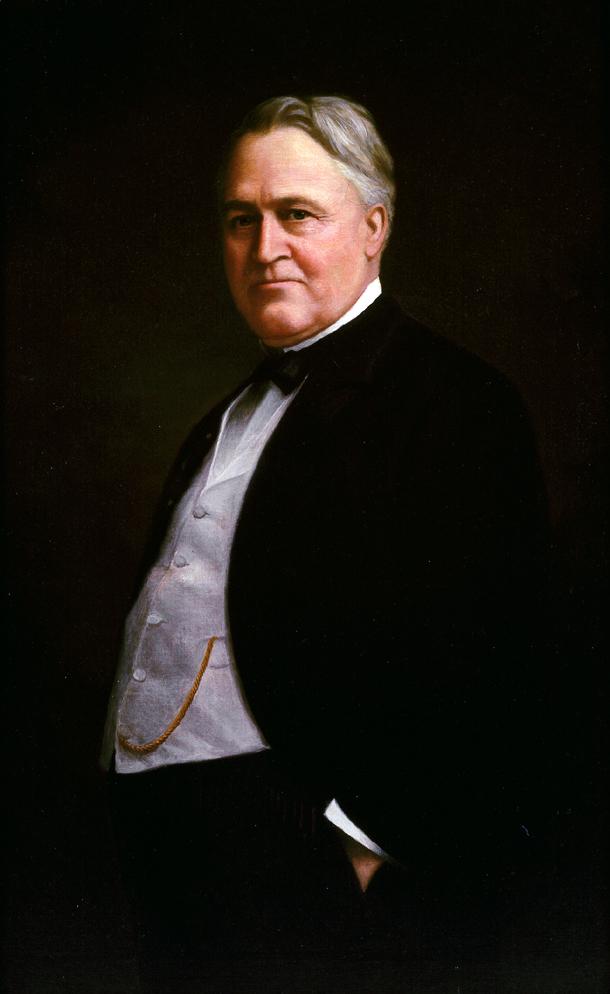

The Postmaster General at the time, Albert Sidney Burleson of Texas, who landed in Wilson’s Cabinet thanks to Wilson’s Texas-born consigliere, Colonel Edward M. House, was characterized by historian G.J. Meyer as “the worst human being ever to serve as Postmaster General.”

Staunchly anti-union and segregationist, Burleson instructed local postmasters to immediately send him any newspapers or magazines that looked suspicious, and said that he was on the lookout for any publication calculated to cause insubordination.

Burleson listed a broad range of statements that would make it fit the latter category, including: “the government is controlled by munitions makers or Wall Street or any other special interests,” and those thought to “attack improperly our allies.”[10]

The first victim of Burleson’s censorship crusade was The Rebel, a socialist newspaper in Halletsville, Texas, which not only opposed the war but had exposed how Burleson had managed a Texas cotton plantation his wife inherited, which employed prison inmates who were whipped if they did not work hard enough.[11]

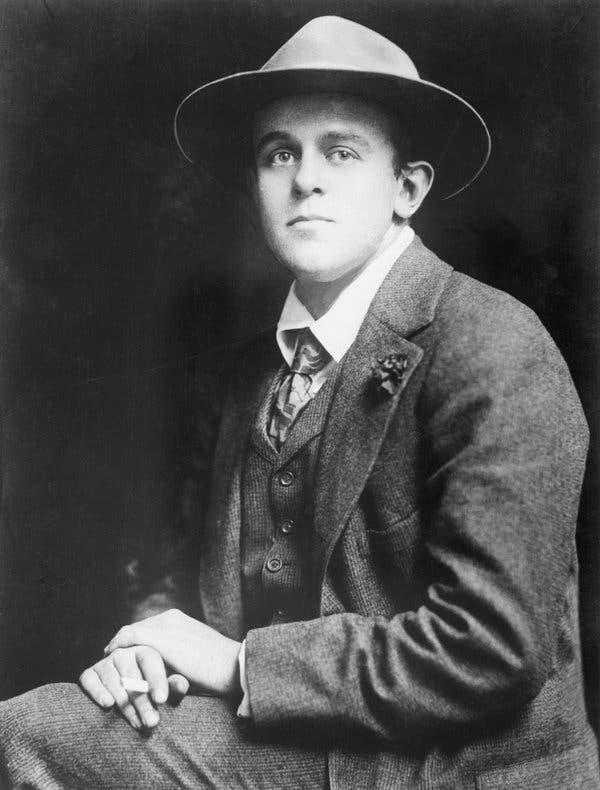

Another major target of Burleson was The Masses, a monthly magazine whose star reporter was John Reed, the founder of the Communist Labor Party of America, which became part of the Communist Party USA.

The editor of the magazine, Max Eastman, who had backed Wilson in the 1916 election because he opposed U.S. entry in the Great War, was put on trial under the Espionage Act.

He was acquitted at trial after Reed testified about the carnage he had witnessed at the front lines in Flanders reporting for The Masses, though the magazine was subsequently halted for good with many others.

Red Emma and the Prairie Socialist

The day Wilson signed a bill mandating the draft, anarchist Emma Goldman’s No Conscription League gathered 8,000 people for a rally in Harlem. A U.S. marshal subsequently led a squad to arrest Goldman and her long-time collaborator and former lover Alexander Berkman.

They were charged with “conspiracy to interfere with the draft,” and hustled off to the Manhattan jail nicknamed The Tombs, a chateau-like building with stone walls, turrets and a high passageway known as the “Bridge of Sighs” connecting it to the criminal courts building across the street.

In the prosecutor’s case against Goldman, there was an echo of the Salem witchcraft trials, when he declared that “her influence is so pernicious,” because as a speaker she could “hold spellbound…the minds of ignorant, weaker and emotional people.”[12]

After being sentenced to two years in prison, Goldman was transferred to the fortress-like state prison in Jefferson City, Missouri, where she became a bunkmate of Kate Richards O’Hare, a Kansas farm girl who was the first prominent Socialist Party figure indicted under the Espionage Act. Her alleged offense was a talk that she gave in Bowman, North Dakota, a “little, sordid, wind-blown, sun-blistered, frost-scarred town,” she recalled, where she was accused of encouraging men to resist the draft.[13]

Despite their different politics, Goldman and O’Hare became fast friends in prison.

Goldman was particularly impressed at how O’Hare brought about improvements in prison conditions after smuggling out a letter about how inmates were forced to bathe in the same tub as a woman who had tuberculosis or pus dripping from syphilis sores.

A Little Hanging Goes a Long Way

An even worse fate than Goldman and O’Hare was reserved for Frank Little, a miner and veteran IWW organizer who marched against the draft in Butte, Montana.

Calling American soldiers “scabs in uniforms,” Little told a crowd of thousands that “we have no interest in the war,” while promising to “make it so damned hot for the government that it won’t be able to send any troops to France.”

A couple of weeks later, masked men seized Little from his boardinghouse, and threw him into a Cadillac Sedan. After a short drive, they tied him to the rear bumper and dragged him along, scraping the skin off his kneecaps. A few hours later, his body was found hanging from a railroad bridge, with scars on his face.

Like with most African-Americans at the time, the police made little effort to solve the lynching—with one of the killers rumored to have been the department’s chief detective (the day after the killing, he began a 20-day leave to allow some scratches on his face to heal).

The Wilson administration also did nothing. Vice President Thomas Marshall cynically coined a pun on the victim’s name. In solving labor problems, he quipped, “A Little hanging goes a long way.”[14]

Brutalization of Conscientious Objectors

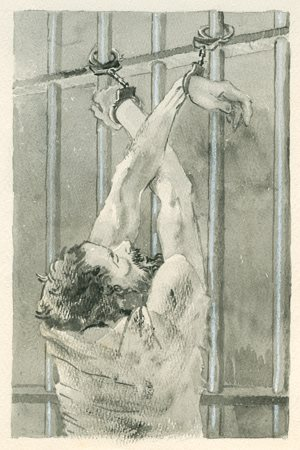

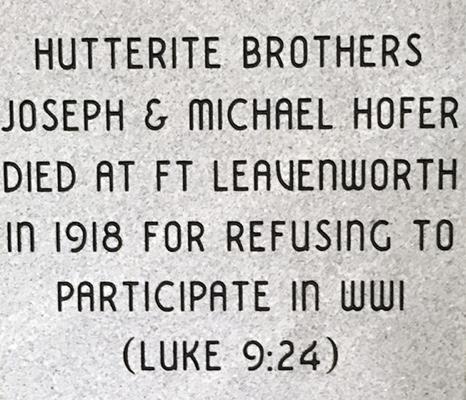

Little’s bleak fate was shared by the Hofer brothers, Joseph, Michael and David, of the pacifist Hutterite sect in South Dakota.

They were shipped to Alcatraz because of their refusal to join the U.S. Army, and hung from the ceiling and placed in basement punishment cells known as the “hole,” where rats roamed freely. “The air in the cell was stagnant,” wrote a CO who was in the Alcatraz hole six months after the Hutterites, “the walls were wet and slimy, the bars of the cell door were rusty with dampness, and the darkness was so complete that I could not make out my hand a few inches before my face.”[15]

After four months, the army moved the severely weakened brothers to the main military prison at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. When they arrived, they were told to undress and had to stand exposed for hours outside.

The next morning, Michael and Joseph complained of sharp pains in their chest and then died several days later.

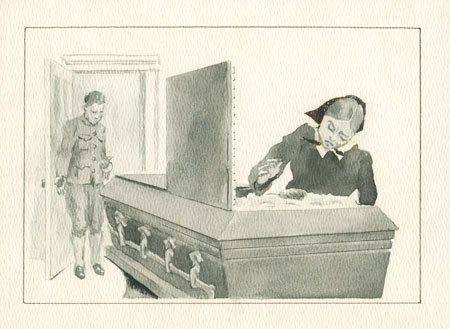

When Joseph’s wife Maria arrived and asked for his coffin to be opened so she could see his body, she was dismayed to find it in a military uniform he had refused to wear when alive.

David Hofer, who survived, wept after his brothers’ deaths. But he could not wipe away his tears, for he was on his feet, his hands chained to the cell bars above him.[16]

Hatred Whipped Up by Wilson’s Propaganda Agency

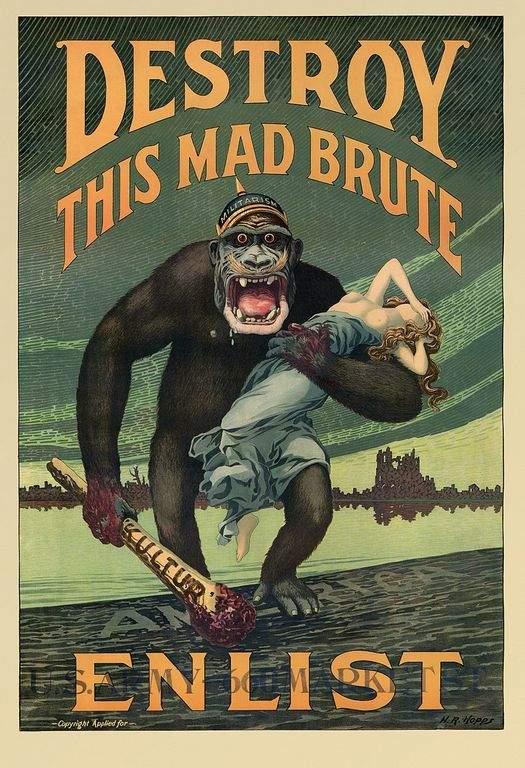

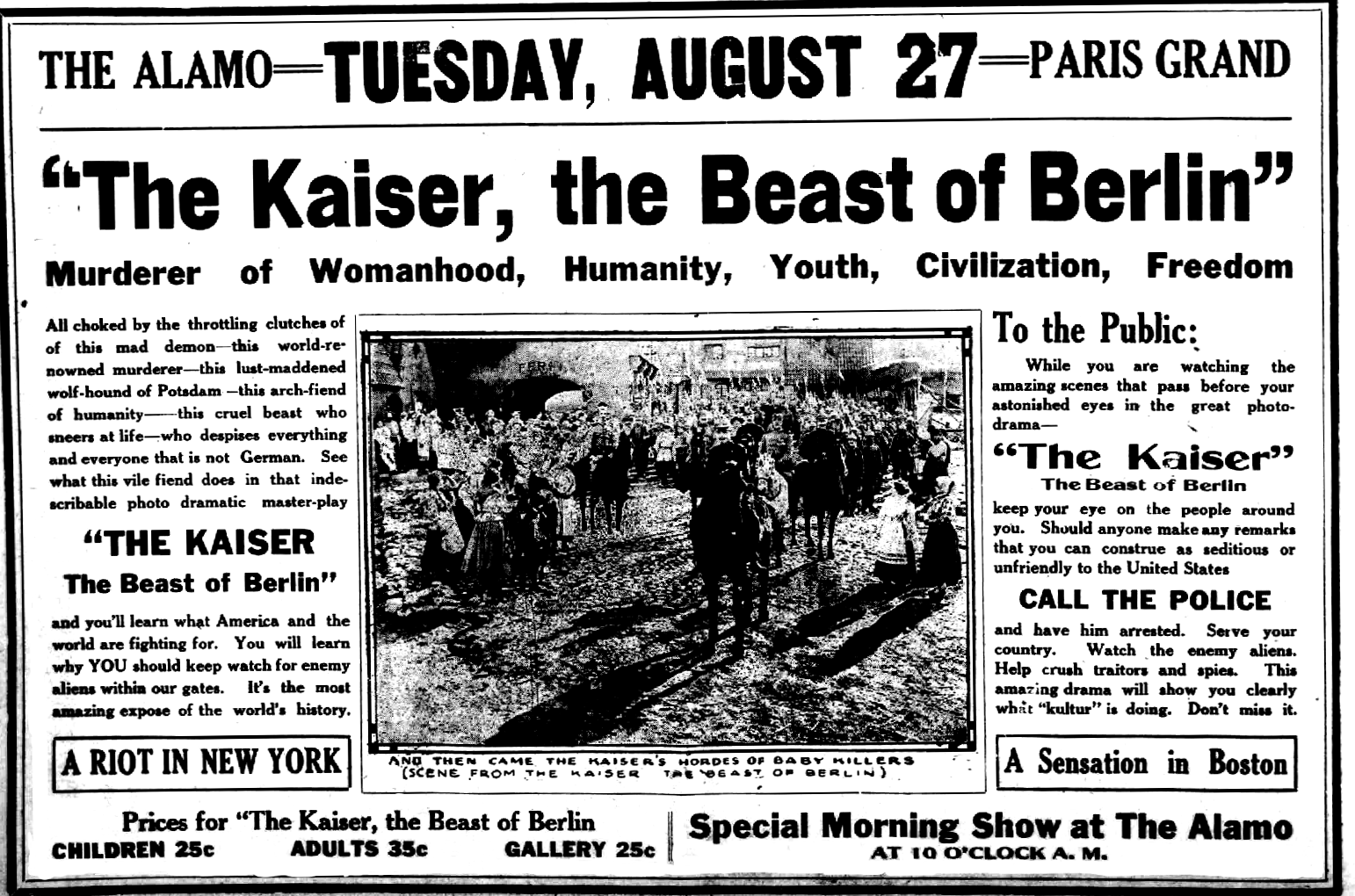

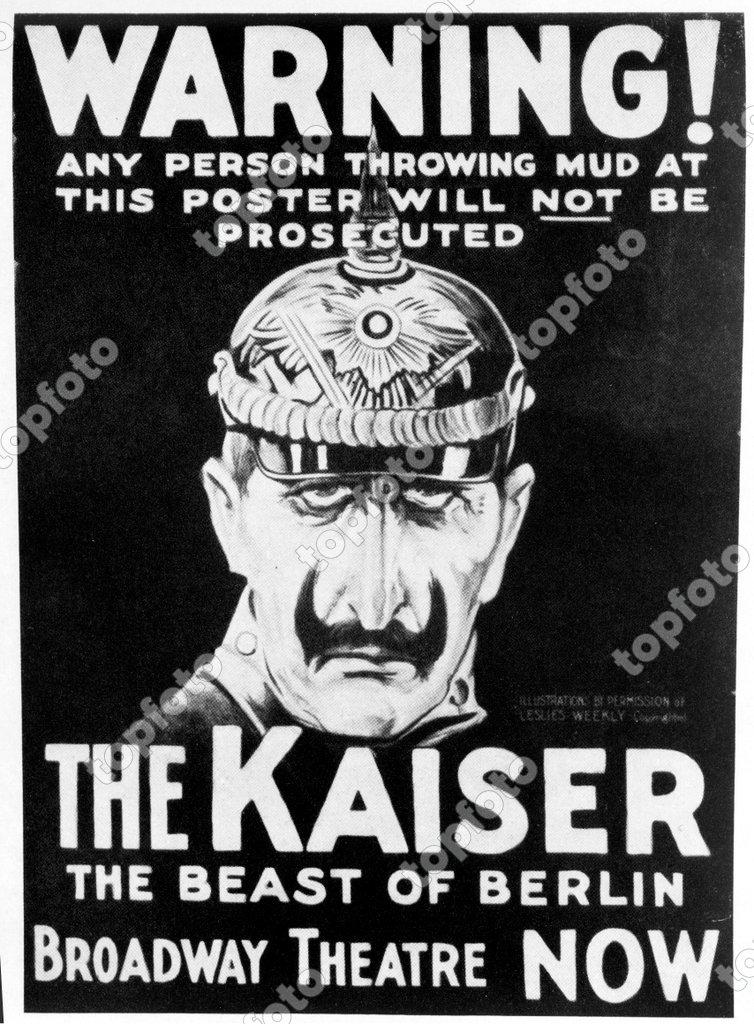

A lot of the hatred in that time period was whipped up by Wilson’s propaganda agency, the Committee on Public Information (CPI).

It employed artists, journalists, filmmakers and novelists, everyone from actress Mary Pickford to author William Dean Howells to eminent professors who “turned out pamphlets on the historical roots of German perfidy.”[17]

Thousands of CPI advertisements appeared in newspapers and magazines, which warned of German agents infiltrating the U.S. and depicted Germans as brutes out to destroy the world—if America did not step in to save the day.

Commercial moviemakers followed the CPI’s lead, churning out silent films like The Slacker, in which a cowardly draft dodger realizes the evil of his ways and enlists, along with other films that demonized Germans, such as The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin and The Claws of the Hun.

In the not too distant future, we might see a sequel: Vladimir Putin: The Beast of Moscow.

Russian Revolution and the Red Scare

The anti-German fervor metamorphosed into the “First Red Scare” following the November 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, which aroused panic in America’s upper class.

The Overman and other congressional hearings spread disinformation about the revolution; witnesses claimed it was part of a “Jewish plot” and that the Bolsheviks had even “nationalized women.” [i.e. taken ownership of them]

Vigilantes began attacking Socialist Party headquarters in cities like Boston and New York, where they smashed furniture and beat party members with clubs.

The worst abuses were carried out during the Palmer raids, named after Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, whose house had been bombed. According to Hochschild, the raids “marked the beginning, largely under [Palmer’s] leadership, of a domestic war the likes of which the United States has never seen.”[18]

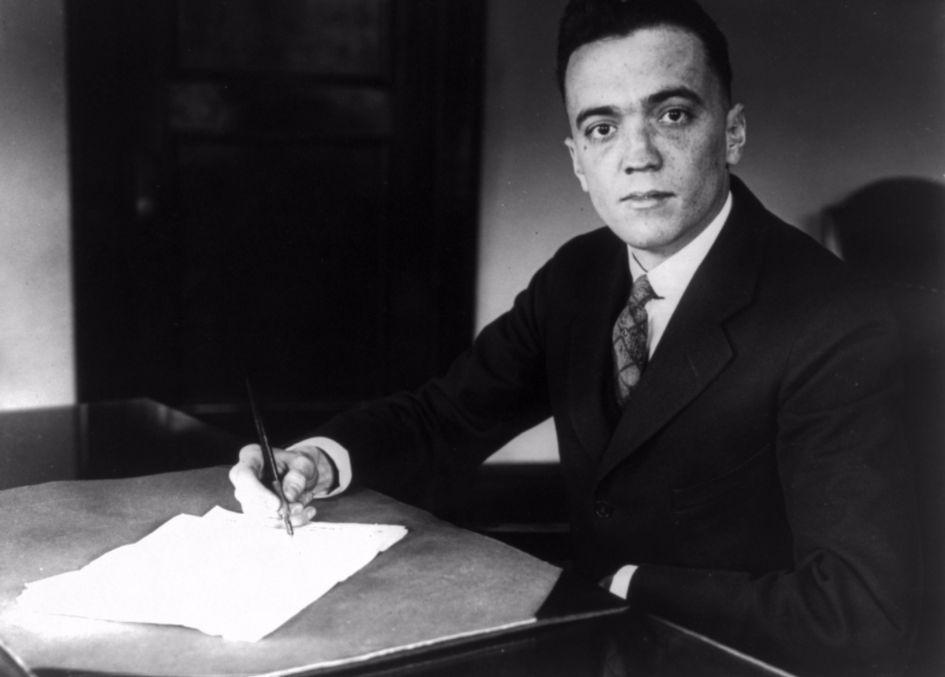

A key figure in running the domestic war was a young J. Edgar Hoover, who presided over the FBI’s newly established Radical Division, which spied on, rounded up and arrested left-wingers in a prelude to the FBI’s counter-intelligence program (COINTELPRO) that Hoover presided over during the Second Red Scare.

Hoover had attracted attention for developing an efficient filing card system while working at the Library of Congress. Now, he developed three-by-five-inch cards for each individual he thought suspicious—including elected officials like Robert La Follette—and for “subversive organizations,” publications, places and events.

This pleased many corporate executives, who saw how anti-communist hysteria could be used to weaken the labor movement and political left, keep wages down, and secure high profits for themselves.

Will History Be Repeated?

George Santayana famously said that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” which is what we are seeing in the U.S. today.

With history education devalued, few people in the country may be aware of the deceits Wilson used to sell American intervention in the Great War and the lengths that his administration took to whip up hatred for Germany and manipulate public opinion; nor the extent to which his administration used a war-time climate to wage a war on left-wing political ideas and groups, which were effectively destroyed.

Few people today recognize some of the same patterns of disinformation—in support now of a war with Russia and potentially China—and the same whipping up of hatreds and efforts to demonize and censor dissenting voices.

Whether America again sinks to the depths of the World War I era is unlikely simply because the left wing has been almost completely neutered since Wilson’s time—and so does not scare the elites in the same way as it once did, and necessitate a violent counter-reaction.

America is now a declining world empire, nevertheless, and its aggressive provocations directed against China and Russia could trigger another world war that would make the first almost seem like child’s play given the evolution of military technologies over the last hundred years.

-

See Harry Elmer Barnes, The Genesis of the World War: An Introduction to the Problem of War Guilt, rev ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1929). See also Roger Peace and Jeremy Kuzmarov, “Historiography: Contested Histories of the Great War,” http://peacehistory-usfp.org/ww1-hist/ ↑

-

Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (New York: Mariner Books, 2022), 33.

Hochschild, American Midnight, 41.

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 42. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 45. ↑

-

Johnson had been part of vigilante group whose members wore white badges and roughed up Wobblies in the streets. A local businessman described how, during a stormy 1912 strike, before Johnson went to Congress, “we got hundreds of heavy clubs of the weight and size of pick handles, armed our vigilantes with them, and that night raided all the IWW headquarters, rounded up as many of them as we could find, and escorted them out of town.” A political enemy claimed Johnson had “packed the strikers into box cars, closed the air vents, nailed the doors shut, and labeled the cars “cattle for Kansas City.” Subsequently, a newspaper that he owned called for a Wobbly’s lynching after one was arrested on charges of murder. Hochschild, American Midnight, 88. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 60. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 61. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 185. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 63. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 64. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 79. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 129. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 105. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 147. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 148. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 175. ↑

-

Hochschild, American Midnight, 240. Historian Alan Brinkley called the Palmer raids “arguably the greatest single violation of civil liberties in American history.” Another contender for the title is the Japanese internment during World War II. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.

Here is a short video exposing more lies about World War I.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=psXYMiBM1JE&t=15s