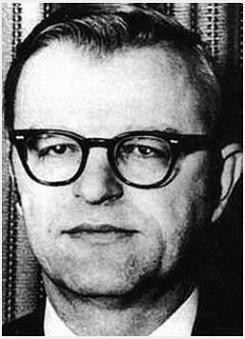

The Secret Team was a group of CIA agents run by CIA’s “Blond Ghost” Theodore Shackley that was involved in the most scandalous U.S. foreign policy interventions throughout the 1970s and 1980s, including the “October Surprise” and Iran-Contra affair. Now, Shackley’s “secret team” has been found to have had extensive connections to the assassination of Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro (1963-68 and 1974-76) by parliamentary commissions of inquiry in Italy and independent investigations.

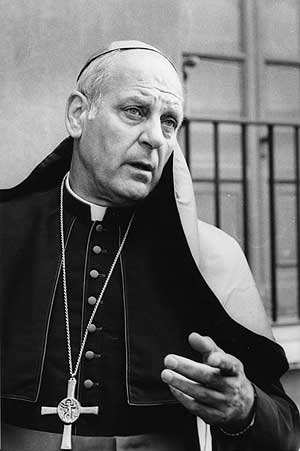

Moro was long the nemesis of powerful conservative factions of the U.S. establishment, due to his insistence on engaging in direct political cooperation with the Italian Communist Party (PCI).

Secret Team member Edwin P. Wilson and his associate Frank Terpil, both former CIA officers, were running extensive operations in Qaddafi’s Libya, including delivery of weapons and military explosives, political assassinations and training and logistical support to various international terrorist groups, including the Italian Red Brigades, officially responsible for the kidnapping and murder of Moro in 1978.[1]

For some of these illegal activities, Wilson was indicted and convicted by the federal government in the early 1980s and spent 20 years in prison.

In his trial defense, Wilson always maintained that he had conducted such operations on behalf of his former employer, the CIA.

A fraudulent affidavit signed by a top CIA official persuaded a U.S. jury that the Agency had terminated professional contacts with Wilson as of 1971.

However, subsequent investigations, initiated by Wilson and his attorney, exposed the government fraud, proving that Wilson had continued to operate for the CIA until at least 1982.

The documentation concerning the Secret Team connection to the Moro operation remains classified.

The Groundbreaking Findings of the New Moro Commission

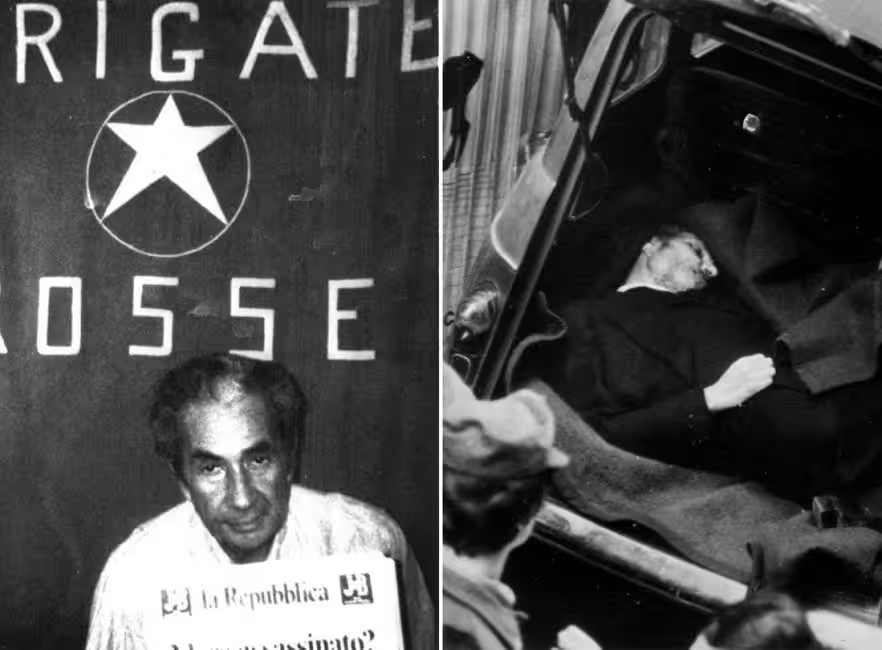

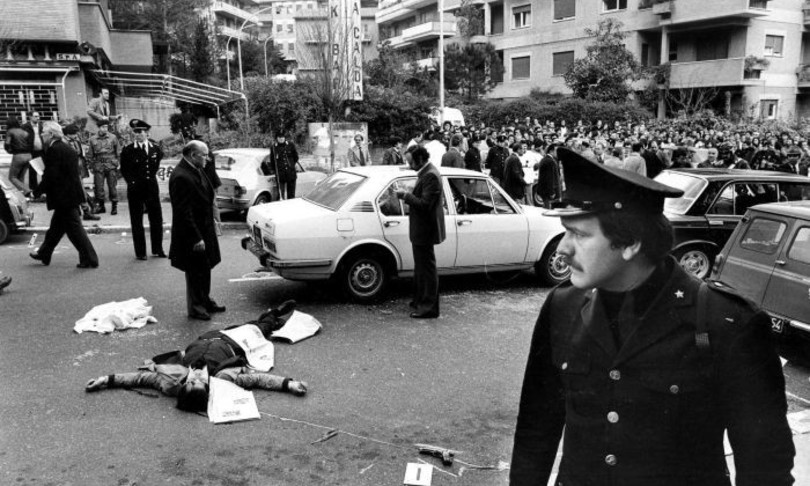

According to the official record, Italian Christian Democracy President Aldo Moro was kidnapped by a radical left terror group, known as the Red Brigades, in Rome, on March 16, 1978.

Moro, escorted by a very tight and professional security detail, was on his way to the Italian Parliament, where the order of the day was the discussion, for the very first time, of the possible participation of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in a coalition government.

Moro was ultimately assassinated, and his body found in the back of a red Renault in the center of Rome, on May 9, 1978.

The official account, defended most stubbornly to this day, has always been that the Red Brigades had acted alone, without any significant external, especially governmental, intervention.

This author has reported about the intractable flaws and inconsistencies of the official narrative, and how that led to the establishment of a second parliamentary commission of inquiry into the Moro case, more than 35 years after the fact.

The last Moro Commission operated between 2014 and 2017, uncovering extremely valuable evidence and producing several final reports, the findings of which were largely inconsistent with the mainstream account.

It is now necessary to focus on the most sensitive discoveries of the Commission, particularly its reference to the Secret Team.

The details of Moro’s imprisonment and agony in the spring of 1978 have always been a matter of intense debate.

A particularly and persistently disputed point is the real hideout(s) where Moro was kept immediately after his kidnapping in Via Fani, Rome.

Multiple independent investigations and the last Moro Commission uncovered evidence that housing units in Rome, in Via Massimi 91 and 96, were used as Moro’s prison after the Via Fani operation.

The units in question were owned by the “Institute for the Works of Religion” (IOR), the financial arm of the Vatican, implicated in highly controversial criminal episodes in the 1970-1980 timeline, and run by the even more controversial American archbishop Paul Marcinkus, who had strong ties to the Masonry and the U.S. intelligence establishment.

More disturbingly, the Via Massimi 91 address also turned out to be the fiscal domicile of the U.S.-based Tumpane, identified in these operations as “Tumco” (also referred to as “Tumpco”), an “American company which had provided services to NATO and the U.S. [military] in Turkey.”

The Moro Commission was able to acquire evidence that “Tumco was engaged in intelligence activity to the benefit of a U.S. military intelligence entity based in Via Veneto in Rome, generally known as the ‘The Annexe.’

Taking into account the Italian operations of Tumpane, [Tumco] officially supported the U.S. radar monitoring network supporting NATO, named Troposcatter/NADGE.[2]

The Commission noted that these activities had not been properly disclosed to competent Italian authorities.

These revelations are significant enough. Yet, one cannot fail to add that Via Veneto in Rome is also the street of residence of the U.S. Embassy.

The Commission also found out that the Via Massimi unit had seen the extensive presence of Omar Yahia (1931-2003), a Libyan financier tied to Libyan and U.S. intelligence.

Yahia “collaborated extensively with Italian intelligence services” and “was, most likely, the person who put in touch the source ‘Damiano,’ who provided quality information on the Red Brigades to Italian intelligence.

His operations in Via Massimi 91 confirm the density of intelligence presences in that condo.”[3]

Evidently aware of the extremely sensitive nature of these findings, and already subject to an incredible amount of pressure, the Commission ordered the classification of the entire documentation concerning the intelligence connections in Via Massimi.

Shortly after the Moro Commission terminated its operations, however, one of its ranking representatives, Marco Carra, made more explicit and unsettling comments.

After pointing out the many investigative breakthroughs of the Commission’s work, Carra singled out the Secret Team specifically: “Omar Yehia [was] in touch with the Secret Team, an anti-communist structure set up by U.S. intelligence operatives, both in service and retired, conceived to make up for the CIA constraints resulting from the Watergate scandal reforms. It is worth bearing in mind this name, Secret Team, because it could come back to the forefront of the Moro affair as a very ‘protagonist’ actor.”[4]

This explosive comment by representative Carra, which also clearly proves that the Commission knew more than what it was willing to enter into the public record, was quickly eclipsed.[5]

Journalists and investigators familiar with the case, recently contacted by the author, confirmed that Carra has been extremely reluctant to revisit this episode and has avoided the subject altogether.

Such recent and groundbreaking developments, concerning the U.S. intelligence connection to the Moro affair, acquire even more value (and the ensuing, massive cover-up becomes more understandable), when viewed in the historical context of the U.S. investigation into Edwin Wilson and the Secret Team.

The sensitive information exposed by the last Moro Commission dovetails perfectly with the original investigations by U.S. authorities, which ultimately led to the indictment and conviction of Wilson in the early 1980s.

Extensive illegal operations of the Wilson group, particularly in Qaddafi’s Libya, were then exposed, sometimes leading to stunning connections of the “Secret Team” to international terrorism, including, which matters more to our case, in Italy.

In June 1981, quoting one such investigation from federal authorities, Seymour Hersh reported for The New York Times that the logistics and training provided by Wilson’s group were exploited in “support of such terrorist groups as the Palestine Liberation Organization, the Red Brigades of Italy, the Red Army of Japan, the Baader-Meinhof gang in Germany and the Irish Republican Army.” [Emphasis added.]

It was by moving from, and expanding on, these initial findings that two Italian investigative journalists, Mimmo Scarano and Maurizio de Luca, in their early work on the case, first advanced the theory that the two “Secret team” agents, Wilson and Terpil, were involved in the Moro affair, which stands largely vindicated today.[6]

The findings of the Moro Commission on Libyan operative Omar Yahia are also supported by the original investigations into this highly controversial figure, who enjoyed extensive connections to, and protection from, U.S. and international diplomacy and intelligence.

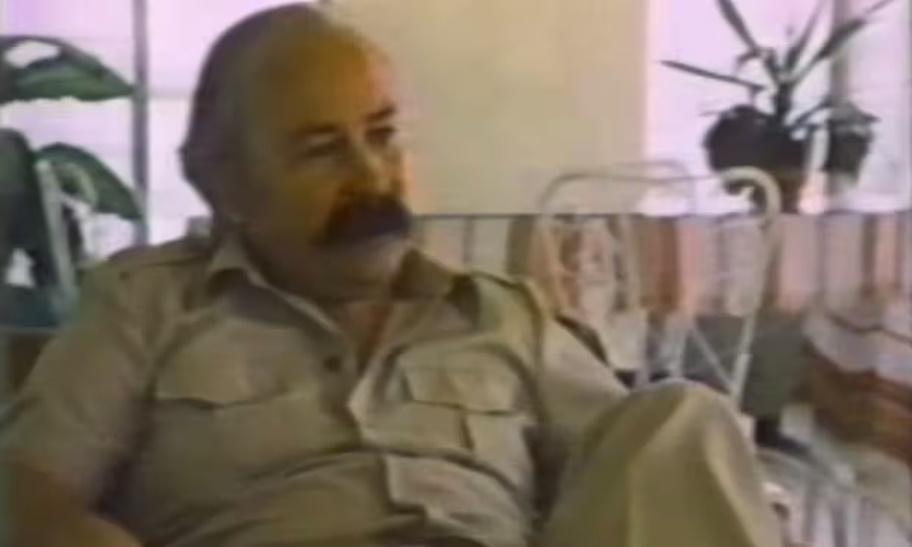

High-level insiders in the special forces known as the Green Berets, such as Luke F. Thompson, repeatedly went on record to confirm that they were dispatched to Libya to train terrorists, supervised by Wilson and Terpil, under the understanding that the whole operation had been sanctioned by the CIA.

The mention of the Green Berets in this affair is of great significance.

Kevin P. Mulcahy, a former CIA agent himself and a key whistleblower in the Wilson-Libya connection, referred to an unspecified “Italian involvement” with the Green Berets being trained in Libya.[7]

The possible presence of a Green Beret among the commandos that masterminded the Moro operation in Rome, has emerged repeatedly in Italian investigations.[8]

As has been noted since almost the inception of the inquiry into the Moro case, the Italian terrorist group known as the Red Brigades did not have—not remotely—the military training or operational capacity to execute such a complex action as the kidnapping of a high-profile political leader like Moro, who was escorted by five experienced law enforcement officers who were all killed in the operation.

Ballistic experts have claimed consistently that the operational team in Via Fani must have included at least one professional military shooter flanking the official Red Brigades.

Senator Sergio Flamigni, the most prominent researcher of the Moro case in Italy, commented that, as to this unidentified shooter, investigations should focus on “the Libyan airplane heading to Geneva which, in the late afternoon of March 15, 1978 (the day before the Via Fani massacre), landed in [Rome’s] Fiumicino Airport instead, with four people on board, to take off again the following day…That flight is strongly suspected of having carried one or more killers affiliated with a particular structure training and supporting terrorist organizations, established in Tripoli (Libya) by Edwin P. Wilson and Frank Terpil, both former CIA agents.”

Despite the astonishing nature of these developments, a thick layer of stone-cold silence has fallen on the case and the findings of the Moro Commission.

In the U.S., the silence is even more deafening. In the virtually unique case when the results of the last Moro investigation were addressed, U.S. mainstream academia set a new standard of denial, claiming that “the commission thus took a ‘ghost story’ approach to the case, but then found absolutely nothing to bear out any of the conspiracy theories. The parliamentary investigators produced a vast quantity of documents without adding anything of substance to our knowledge about Moro’s tragic end.”[9]

Kissinger’s nightmare: The Italian Communist Party and Moro’s “Historic Compromise”

How did agents of the U.S. establishment end up being connected to one of the most notorious criminal cases of the 20th century, targeting a major political leader of an allied country?

As it happens, the story between Moro and the U.S.-NATO establishment accounted for a long series of reciprocal misunderstandings, distrust and ultimate hostility.

It would be accurate to state that Moro and the U.S. went back a long way.

As a matter of fact, Moro had already ignited intense controversy in the U.S. in the early 1960s, because of his efforts to involve the Italian Socialist Party in a political coalition with the Christian Democracy Party.

Yet, it was certainly Moro’s policy of seeking political involvement of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in Italy’s government—the so-called “Historic Compromise” in the 1970s, justified, in his view, by the indisputable influence of the party in Italy’s politics and society—which drew the fatal ire of the U.S. (and others).

It is true that the PCI, with its strong ties to Moscow, had always been a source of extreme concern for the U.S., since the end of the Second World War.

It is a matter of record that the first major operation of the CIA was indeed aimed at preventing an electoral victory of the PCI in the crucial Italian elections of 1948.

From the U.S. standpoint, Italy, since 1949 a crucial NATO ally in Southern Europe, hosting a large number of U.S. bases, simply could not be allowed to “go communist.”

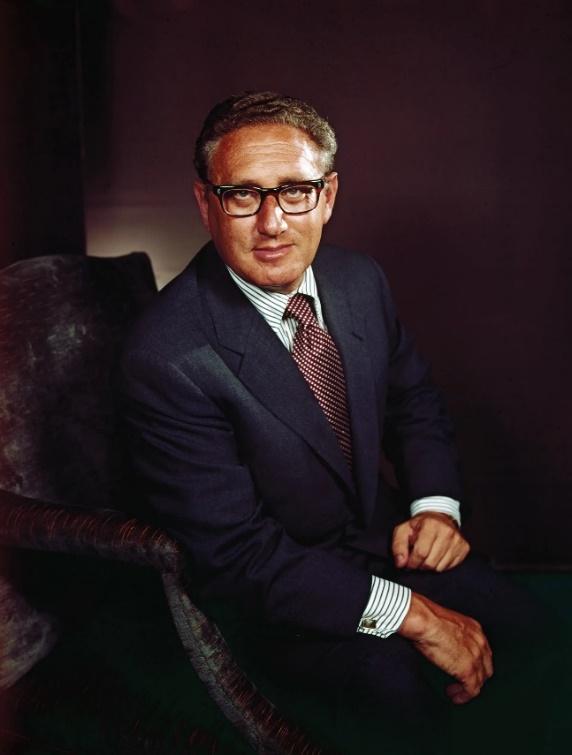

Very few representatives in the U.S. political and diplomatic establishment epitomized the hostility toward Moro’s policies more than Henry Kissinger.

The obsession of Kissinger with the Italian PCI actually verged on the pathological.

So extreme was the sensitivity of Kissinger to this issue that he constantly referred to Italy, almost reflexively, any time the possibility of a “communist,” if not just “socialist,” takeover would materialize anywhere in the world, regardless of how grounded in fact such concerns were.

The National Security Archive of George Washington University, which conducted prodigious research unveiling the U.S.’s extensive subversive activities in South America, and Kissinger’s role in them, documented quite an enlightening episode.

The recently declassified record shows that plans to remove Salvador Allende from power in Chile were actually devised early on, shortly after Allende’s historic electoral victory in 1970.

Central to the hostility against the Chilean leader was the fear that his case could be replicated elsewhere in the world, including Western Europe.

In a briefing memo addressed to President Nixon, in preparation for the crucial NSC meeting which took place on November 6, 1970, Kissinger struck a very ominous note, anticipating the darker course of actions ahead: “The election of Allende as President of Chile poses for us one of the most serious challenges ever faced in this hemisphere…Your decision as to what to do about it may be the most historic and difficult foreign affairs decision you will have to make this year…for what happens in Chile over the next six to twelve months will have ramifications that will go far beyond just U.S.-Chilean relations.”

Elaborating on the ramifications of an accepted “Marxist” government such as Allende’s, Kissinger warned that Allende’s “model effect can be insidious”:

“The example of a successful elected Marxist government in Chile would surely have an impact on—and even precedent value for—other parts of the world, especially in Italy; the imitative spread of similar phenomena elsewhere would in turn significantly affect the world balance and our own position in it.” [Emphasis added.]

A quote oscillating between creative ways to endorse democratic processes and quite evocative “domino theory” interpretations applied elsewhere in the world, particularly in Southeast Asia, with not exactly enthusiastic outcomes.

In fact, Kissinger almost overwhelmed the historical record with his anti-PCI outbursts.

The volumes of the Foreign Relations of the United States published in the past decade, concerning the Ford administration’s policy on Western Europe and NATO, exhaustively illustrate Kissinger’s obsession with the Italian case.

A September 1975 meeting between Kissinger and European senior officials, gathered in New York to discuss Europe’s “Southern flank,” and the possible participation of “socialist” parties in the region governments, is a case in point.

The discussion was overwhelmingly dominated by the obsessive fear that any “opening to the left” in Southern Europe, regardless of how moderate, could represent a dangerous precedent for Italy and benefit the Italian Communist Party politically.

The connection to Italy of any détente policy with European socialist parties returns endlessly in the meeting, and the verbatim quote of not creating “a precedent for Italy” is repeated three times, with Kissinger stating it twice in the span of a few paragraphs.

The centenarian statesman was not shy in expressing his radical hostility to the possible opening to the PCI directly to Aldo Moro, irrespective of the actual intentions of Moro and of any moderation process the PCI was engaged in at the time, which would accept Italy’s membership in NATO.

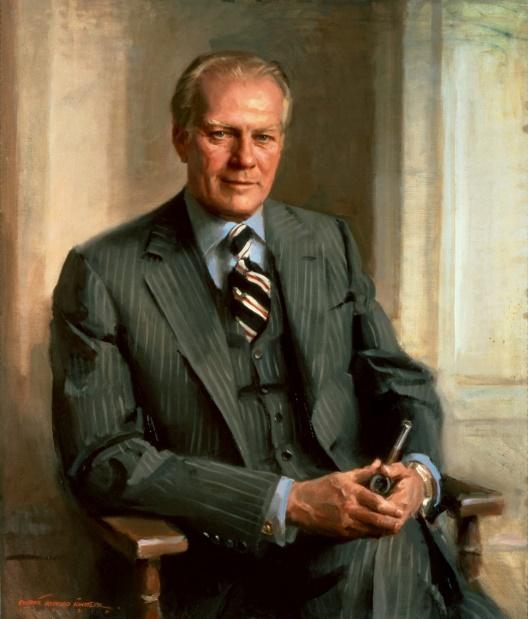

Shortly before the New York Summit, on August 1, 1975, Ford, Kissinger, Moro and then Italian Foreign Minister Mariano Rumor met on the occasion of the famous Helsinki security accords, in Finland and the discussion centered again on European security.

The theoretical possibility of the PCI joining the Italian government was again on the table, and the conversation escalated rapidly.

Regardless of the political merit of each side’s case, the incredibly tense exchange and the harshness and tone used by Kissinger toward Moro (on that occasion acting as Italy’s Prime Minister!), certainly not usual between representatives of two allies, especially in an official meeting, is still striking almost half a century later.

After Moro attempted to represent the difficult balancing act of the PCI with respect to NATO and its particular influence in Italian politics, Kissinger went off:

“Secretary [Kissinger]: If I may speak more bluntly than the President, we don’t care if they [the PCI] sign onto NATO in blood. Having the communists in the Government of Italy would be completely incompatible with continued membership in the Alliance. There is a difference between an election tactic and reality. There is no way that we can be persuaded to be in an Alliance with governments including communists which is supposed to be against communism, no matter what you say.

President [Ford]: Henry is a very subtle diplomat.

Secretary [Kissinger]: If the President wants me to, I can say these things in undiplomatic language.”[10]

The exchange may be regarded as being eloquent enough.

Suspicious minds may infer that, if U.S. officials were not afraid of sending such stern warnings in official meetings, they could be even more transparent off the record.

In fact, what the official government record does not, and cannot, reflect is the way more sinister machinations were taking place behind the scenes, in order to force Moro to abort his policy of opening to the Communist Party.

Moro told his closest associates, and his wife Eleonora, that senior American officials had explicitly threatened the gravest consequences, in case he did not relent in his “Historic Compromise” strategy toward the PCI.

The most serious episode had occurred in September 1974, in connection with several high-level meetings that an Italian government delegation, including Moro, then foreign minister, and Italian President Giovanni Leone, held with U.S. officials, notably President Ford and Henry Kissinger.

German Chancellor Willy Brandt had reportedly warned Moro of “a worrying coalescence of hostile forces” against his politics, connected to “strong U.S. interest groups.”

Moro was advised to accept a confidential meeting with a U.S. intelligence official to discuss his policies opening to the left.

The meeting would take place in the residence of the unidentified officer, located in the hinterlands of New York.

While the Italian delegation was engaged in a social event, Moro went, escorted only by a trusted member of its security detail, Marshal Oreste Leonardi.

During the sinister meeting, Moro was told—in unequivocal terms—that the U.S. establishment opposed his policies and that there existed “firm resolution, within U.S. intelligence as well, to disrupt his policies.”

U.S. opposition was not confined to “his progressive opening to the PCI,” but extended to Moro’s détente policies with the Arab world.

The Christian Democracy leader was also alerted to the fact that, to that effect, “groups operating on the side of intelligence services, strictly speaking, could be deployed to exert direct pressure,” hence suggesting possibly more dangerous consequences, given the plausible deniability associated with such groups.

The U.S. official, while showing “an understanding for the arguments of Moro overall,” also encouraged Moro “to take a detached look at a reality, which could result in situations as unpleasant as unthinkable at the time.”[11]

Several close associates of Moro reported that, shortly after that meeting, Moro cancelled all his pending engagements and fell ill.

These hyper-confidential, sensitive disclosures were corroborated, in their substance, by top insiders’ depositions.

Moro’s widow, testifying to the first Italian Parliamentary Commission investigating the case, confirmed that her husband had received explicit threats: “It was one of the very few times my husband quoted precisely what they had told him, without citing the name of the person in question.”

The unnamed official made unsubtle comments to Moro, to the effect that “he must stop pursuing his political plan to get all the political forces in his country to work together. So, either he’d stop doing so or he would pay dearly for it. It was up to him how to interpret that.”

Corrado Guerzoni, a long-time associate and close friend of Moro revealed equally disturbing details.[12]

Returning from that traumatizing encounter in the U.S., in September 1974, Moro told Guerzoni that he intended to withdraw from politics altogether.

Moro directly “blamed the American pressures for his [expected] withdrawal from politics” and added that he was also threatened by the following: “If you go on like that, your country will be economically strangled.”[13]

Moro was indeed increasingly isolated after that eventful meeting.

A change in the political scene provided for a temporary respite, and Moro did not follow through on his contemplated decision to quit Italian politics.

Yet, the Italian political landscape remained extremely unstable, and the persistent influence of the PCI continued to dominate and poison U.S.-Italy relations.

The Steve Pieczenik mystery

It might be objected, in principle, that the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro took place in the spring of 1978, hence during the Carter, not Ford, presidency, when the Republicans and Kissinger were no longer in control.

The political changes, real or assumed, in Carter’s foreign policy, compared to his predecessors, cannot be discussed herein, but they do not really bear, in a substantial manner, on the question of U.S. policy toward the PCI.

Even the official record shows conclusively that, while articulated in a more diplomatic fashion, Carter’s U.S. foreign policy toward “euro-communism” did not significantly diverge from the previous administrations.[14]

In a manner, that was almost inevitable, as the PCI, in the national election of 1976, while not obtaining the hoped-for result (or even the electoral victory, as feared paranoically in U.S. circles), still received a record 34.4% of votes, making the case for the “Historic Compromise” with Christian Democracy, in Moro’s and other politicians’ eyes, even more compelling.

Furthermore, staunchly conservative and anti-communist forces were adequately represented in the Carter administration as well, most significantly in the person of National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, who exerted considerable leverage on the foreign policy making concerning Italy.

It is also inaccurate to contend that Kissinger was out of the picture, simply because he no longer occupied government positions.

It is well known that the now 100-year-old statesman continued to hold significant sway in the U.S. foreign policy establishment, which carries on even today.

In any event, the Carter administration ultimately announced publicly its hostility to the presence of communists in any Italian government.

In January 1978, just two months before the Moro kidnapping, the State Department issued an official communiqué, summarizing the position of the White House.[15]

Carter, essentially, issued a warning to French and Italian democratic leaders against inviting the Communists to join their governments.

According to the president, it was precisely when democracy was up against difficult challenges that its leaders had to show “firmness in resisting the temptation of finding solutions in nondemocratic forces.”

“Administration leaders have repeatedly expressed our views on the issue of Communist participation in West European governments. Our position is clear: we do not favor such participation and would like to see Communist influence in any Western European country reduced….The United States and Italy share profound democratic values and interests, and we do not believe that the Communists share these values and interests.”

Whatever the ultimate chain of command was in the Moro operation, which cannot be ascertained, the long hand of U.S. intelligence assets was ubiquitous in it.

Keep in mind that the Italian Government Crisis Committee, established by Interior Minister Francesco Cossiga to manage the Moro kidnapping crisis, was extensively infiltrated by the notorious Masonic Lodge P2, headed by U.S. asset Licio Gelli, including the heads of Italian military and civil intelligence at the time.

Bear in mind also the neo-fascist orientation of the U.S.-backed P2 Lodge: One is hard-pressed to find in history a comparable case, where the fox is tasked with watching the hen house.

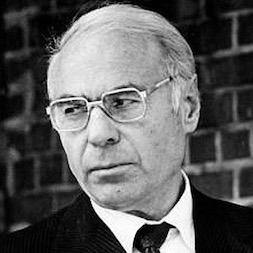

It was not until the first decade of the 21st century, however, that the role of another, extremely ambiguous U.S. emissary became known.

Cuban-born with Polish heritage, a brilliant background at Cornell, Harvard and MIT behind him, Steve Pieczenik was a psychiatrist by training and an expert in terrorist and hostage crisis management at the State Department.

It was in that capacity that Pieczenik was dispatched to Italy in 1978, in order to provide expert advice to the Moro crisis management committee.

It turned out, however, that his role was much more complicated, and darker.

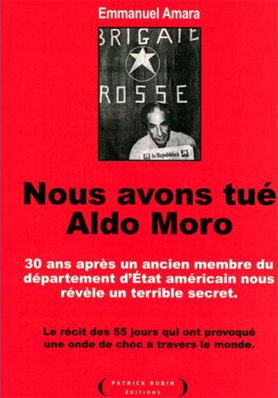

In a 2006 book confession by French journalist Emmanuel Amara, significantly titled “We killed Aldo Moro” (in the original French) and subsequent revelations, Pieczenik admitted that his mission was ultimately oriented “to sacrifice Moro in order to preserve Italy’s political stability.”[16]

Pieczenik was actually very close to Henry Kissinger, and recalled himself in the book that it was “Kissinger and Lawrence Eagleburger who first recruited” him “to create the first crisis and antiterrorism cell in international history.”

Among other disclosures, Pieczenik also admitted that he went so far as to mastermind the infamous “Duchess Lake” communiqué issued during Moro’s imprisonment and attributed to the Red Brigades, which disseminated the false information that Moro was lying dead at the bottom of a lake near Rome.

It was, in the words of Pieczenik, a “psychological operation,” aimed at “preparing the Italian and European public to the possible death of Moro,” which ultimately occurred on May 9, 1978, but also misled investigators away from the real whereabouts of Moro.[17]

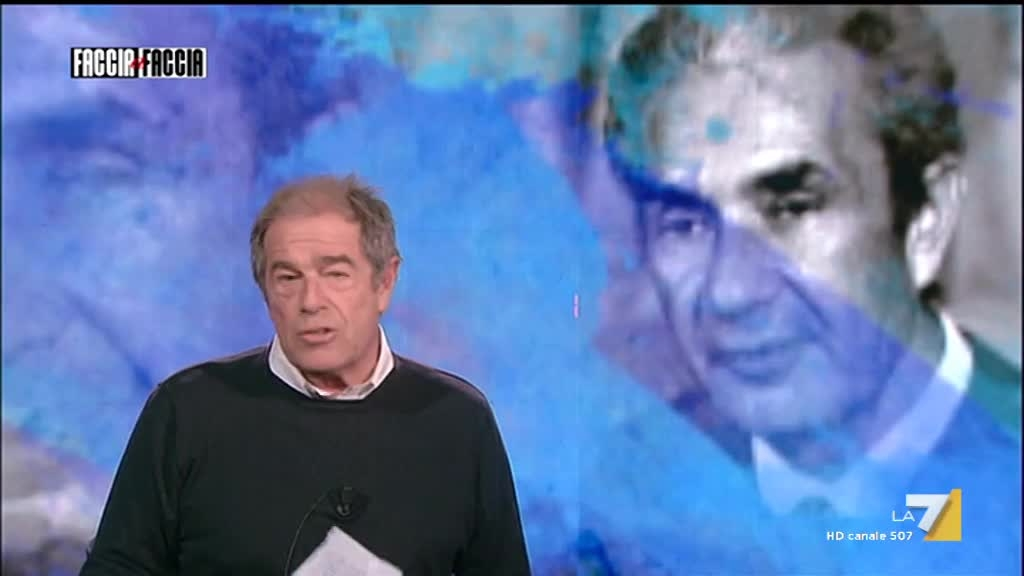

In a 2013 interview with the respected Italian journalist Giovanni Minoli, Pieczenik was even more blunt:

“[SP:] At that time, we were shutting down all the channels through which Moro could have been released.”

[…]

“[GM:] So, basically, since day one you thought and said to Cossiga: Moro must die.”

“[SP:] As far as I am concerned, the thing was obvious. Cossiga realized that only in the last weeks. Aldo Moro was the fulcrum to sacrifice, around which revolved the salvation of Italy.”

The public disclosures of Pieczenik were so unsettling that they not only ignited a significant political firestorm, but also caused Italian prosecutors to open a criminal investigation against the U.S. crisis expert for possible complicity in murder.

According to Rome’s general prosecutor Luigi Ciampoli, “serious evidence suggests the American worked behind the scenes to make sure that Moro’s murder was the only ‘necessary and inescapable’ option left available to his abductors.”

At some point the diplomatic issue became serious enough that, in 2014, the Obama administration compelled Pieczenik to cooperate with the Italian authorities.

In furtherance of a mutual assistance request with U.S. counterparts, investigative magistrate Luca Palamara was able to interrogate Pieczenik.

Quite incongruously, however, Pieczenik was not heard as an accused, but as a fact witness in the murder case.[18]

On July 29, 2015 Palamara was also heard on this highly sensitive matter by the Moro Commission.

The outcome, at this point, is almost predictable. Both the interrogatory of Pieczenik, except for a few excerpts published by the Italian press, and the deposition of Palamara to the Moro Commission, were classified.

The whole matter was almost literally buried and the lead of Pieczenik could not be pursued any further.

While the Pieczenik affair is relatively well-known in Italy, the groundbreaking revelations of the U.S. envoy have been almost entirely suppressed and are unknown in the United States.[19]

United States of America v. Edwin Paul Wilson—the significance of the case for the Moro affair and beyond

Based on the currently available information, it is now possible to connect the dots and draw some troubling conclusions on the CIA-Wilson connection to the Moro affair, and beyond.

First, it is important to note that the criminal activities of Wilson’s group, hence including the support to the Italian Red Brigades, are not in question, nor were they ever.

It was U.S. federal prosecutors themselves, while in the highly selective manner which concealed the CIA connection, that exposed and indicted Wilson’s controversial enterprises.

What was in question, until one of Wilson’s convictions was thrown out, was that he was carrying out such activities while he was still cooperating with the CIA, which the Agency falsely denied, regardless of the official role or connection he may have had with the Agency at the time.

The evidence exposed during the criminal investigation that ultimately led to Wilson’s original conviction to be vacated, in 2003, largely eliminated any doubt on this point.

This final corroboration—on top of the existing, overwhelming evidence—certainly makes a compelling case for U.S. agencies’ accountability in the Moro case.

Yet, it also opens the classical Pandora’s box as to CIA complicity in the myriad other controversial activities in which Wilson and the Secret Team were involved.

It is then quite useful to review the major facts leading to Wilson’s final exoneration, because they reveal how deeply Wilson was actually involved with the Agency and to what extent the CIA and the U.S. government were willing to go, breaking the law repeatedly, to remove themselves from Wilson, clear evidence of the extreme sensitivity of Wilson’s activities.[20]

Furthermore, while the mainstream press was forced to briefly cover the 2003 judgment vacating the conviction of Wilson, it overwhelmingly underreported, downplayed or ignored the judicial case’s highly sensitive information regarding Wilson’s CIA connections, and their cover-up by the U.S. government.[21]

After a 1982 conviction (and a sentence of ten years in prison) in Virginia for smuggling weapons to the Libyans, Wilson was tried again in 1983, in Texas, on charges of shipping 42,000 pounds of C-4 plastic explosive to Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 1977, and then hiring U.S. experts—former U.S. Army Green Berets—to teach Libyans how to make bombs.

Wilson’s defense all along was that he had acted, at least implicitly, under the direction and authority of the CIA.

Wilson presented testimony to the effect that his ties to the Agency were ongoing, and the case outcome was uncertain.

To refute Wilson’s claims, the government introduced an affidavit from Charles A. Briggs, then Executive Director of the CIA, the third-highest ranking official in the Agency.

Briggs stated, under penalty of perjury, that Wilson’s official employment with the CIA had ended in 1971, and that, “according to Central Intelligence Agency records, with one exception while he was employed by Naval Intelligence in 1972, Mr. Edwin P. Wilson was not asked or requested, directly or indirectly, to perform or provide any service, directly or indirectly, for [the] CIA.”[22]

Briggs’s sworn statement turned out to be absolutely false, but it turned the case in favor of the prosecution. In February 1983, Wilson was convicted and sentenced to 17 years in prison.

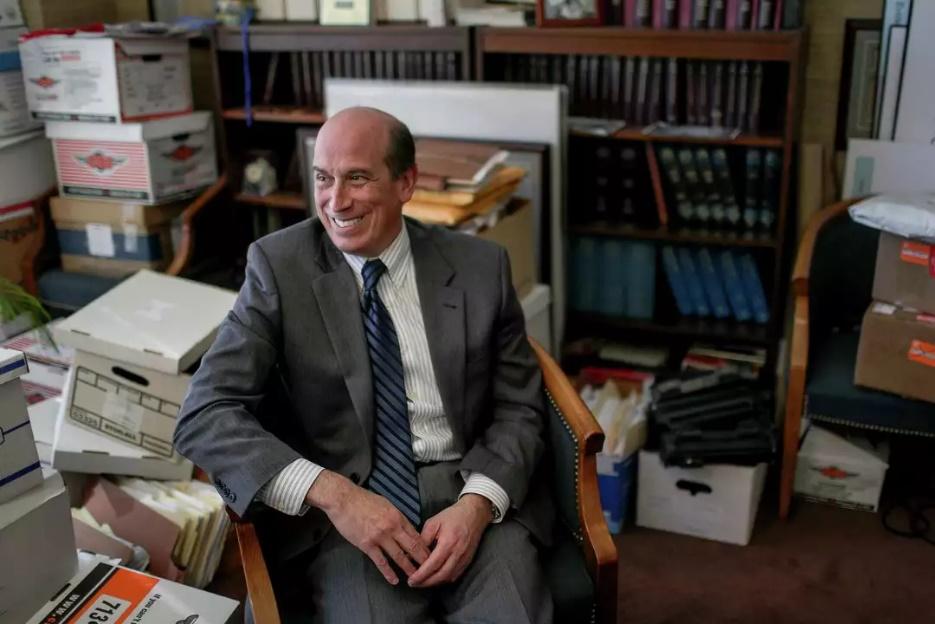

In 1997, through FOIA requests, Wilson obtained documents contradicting Briggs’s affidavit and sent them to U.S. District Judge Lynn N. Hughes. For Wilson’s defense, Judge Hughes appointed attorney David Adler, interestingly enough a former CIA agent himself.

A successful and still-practicing attorney in Texas, Adler was able to review classified CIA and government information for the defense, thus becoming the crucial figure in the reversal of the case against Wilson and, indirectly, in the advancement of the historical truth.[23]

The evidence collected and submitted by Adler exposed a consistent pattern of government misconduct and cover-up, aimed at wiping out Wilson’s connection to the CIA.

First, as Judge Hughes’s Opinion notes, even before the sentencing of Wilson, “the Government admitted internally that [Briggs’s] affidavit was false.”

A CIA investigator had drafted a memorandum for the Inspector General documenting several cases where Wilson had worked for the Agency after 1971.

“The employee who drafted the memorandum had conducted most of the pre-trial investigations on Wilson’s post-employment contacts with the CIA; he knew the Briggs affidavit was false.”[24] [Emphasis added.]

Even more importantly, the new evidence, duly detailed in Judge Hughes’s Opinion, showed extensive and far-reaching cooperation between Wilson and the CIA, well beyond the stated “limit year” of 1971.

Two instances deserve special attention:

When the CIA Inspector General investigated the case, “the magnitude of Wilson’s involvement with the CIA became stark: the CIA found eighty non-social contacts between Wilson and CIA employees, including almost forty times where Wilson furnished services to the CIA between 1972 and 1978.”[25] [Emphasis added.]

It was also revealed that, among the documents that the Justice Department had not turned over to Wilson’s lawyers in the original case, there were lengthy handwritten notes, taken by the prosecutors during a meeting with CIA officials held on July 13, 1982.

The Hughes Opinion notes that, “equally troubling, the notes are derived from documents that were not disclosed to Wilson’s trial or appellate lawyers.…

Several pages of the prosecutor’s notes mirror a detailed chronological summary of the CIA’s use of Wilson and his businesses since 1971. That summary, and four others dating from 1973 through 1982, were circulated within the CIA on October 1, 1982; none was produced.”[26]

It is then conclusively documented that the CIA kept relying, extensively, on Wilson’s services until as late as 1982—and was keeping careful record of it.[27]

The Agency’s own internal investigation had made that clear since the beginning, yet nothing was done to share such crucial information with Wilson’s defense.

In criticizing the government’s misconduct in the case, transparently steered by the imperative need to conceal the U.S. government ties to such an inconvenient and controversial asset as Wilson, Judge Hughes did not mince words:

“Honesty comes hard to the government.…

In the course of American justice, one would have to work hard to conceive of a more fundamentally unfair process with a consequentially unreliable result than the fabrication of false data by the government, under oath by a government official, presented knowingly by the prosecutor in the courtroom with the express approval of his superiors in Washington.”[28]

The implications of this case for CIA responsibility, and complicity in Wilson’s extensive criminal activities, are evident, and supersede the Aldo Moro case.

As to the latter, several conclusions are certainly inescapable now.

It is undeniable that Wilson’s group was indeed still “providing services” to the CIA in the spring of 1978, during the facts of the Moro case.

Also, the Agency was evidently aware, as cited in The New York Times article and other sources, that, through Wilson’s “services,” military training and other aid was provided to several terrorist groups operating in Europe, including the Red Brigades, supposedly implicated in the Moro kidnapping and assassination.

As research into the Secret Team grows and shows how ubiquitous its criminal activities were, so does the need for full government disclosure.

-

For an authoritative review of the Secret Team and Wilson’s controversial activities, and his close, entrenched, ties to top CIA officers like Shackley and Thomas Clines, see the always-relevant biography of Theodore Shackley by David Corn, Blond Ghost (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994; see also Joseph J. Trento, Prelude to Terror: Edwin P. Wilson and the Legacy of America’s Private Intelligence Network (New York: Basic Books, 2006). ↑

-

Final Report of the Parliamentary Commission investigating the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro, December 6, 2017, 268-69. ↑

-

Idem. ↑

-

Ansa, Moro: Carra, Gallinari in via Massimi e spunta il “Secret Team”, December 13, 2017.

-

The ANSA article quoting it, at this writing, is no longer available on-line. ↑

-

Mimmo Scarano and Maurizio de Luca, Il mandarino è marcio: terrorismo e cospirazione nel caso Moro, Editori Riuniti, 1985. ↑

-

L’Europeo, November 15, 1982. Mulcahy was ultimately found dead in a Virginia motel cabin in October 1982. The circumstances were highly suspicious and Green Beret Luke Thompson, another crucial insider in the Libyan affair, clearly stated his belief that Mulcahy was murdered to prevent him from testifying in the trial against Edwin Wilson. ↑

-

Mimmo Scarano and Maurizio de Luca, cit., 119-24. ↑

-

Richard Drake, Moro: L’inchiesta senza finale by Fabio Lavagno and Vladimiro Satta (book review), in Journal of Cold War Studies, Vol. 20, No. 4, Fall 2018, 252-53. ↑

-

In Memorandum of Conversation [originally classified “Secret NODIS”], August 1, 1975, Ford Presidential Library. ↑

-

Mimmo Scarano and Maurizio de Luca, Il mandarino è marcio, cit., pp.25-26, quoting confidential sources, connected to Atlantic services, familiar with the case. In hindsight, while it’s obviously impossible to prove such a connection directly, the possible reference to assets such as the Secret Team as the “groups operating on the side of intelligence services” is blatantly transparent. ↑

-

Eleonora Moro, Testimony to the Parliamentary Commission of Investigation into the Via Fani Massacre, the Kidnapping and Murder of Aldo Moro, August 1, 1980. ↑

-

Corrado Guerzoni, Testimony to the Parliamentary Commission of Investigation into the Via Fani Massacre, the Kidnapping and Murder of Aldo Moro, February 16, 1983. ↑

-

See, in particular, Olav Njølstad, “The Carter Administration and Italy: Keeping the Communists

Out of Power Without Interfering,” Journal of Cold War Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3, Summer 2002, 56-94. ↑

-

Statement Issued by the Department of State, January 12, 1978, American Foreign Policy: Basic

Documents (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 514–15. ↑

-

Emmanuel Amara, Nous avons tué Aldo Moro, Patrick Robin Editions, 2006, 80. ↑

-

Ibid., 140. ↑

-

Magistrate Palamara eventually explained that this choice was intended to prevent Pieczenik from invoking the right not to answer as a defendant Palamara later came to regret his decision. ↑

-

The edition of Amara’s book referred to here is the original French edition. The book has never been translated into English and is largely unavailable in the U.S. market. ↑

-

See especially the Opinion on Conviction issued by Judge Lynn N. Hughes, UNITED STATES of America v. Edwin Paul WILSON, U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas – 289 F. Supp. 2d 801 (S.D. Tex. 2003), October 27, 2003, which represents the leading source for this section and the Wilson criminal case. ↑

-

Wilson’s obituary in The New York Times, September 22, 2012, remarkably concise for an incredibly complex story such as Wilson’s, is a case in point. ↑

-

Ibid., 8. ↑

- The author has been in contact with Attorney Adler, who has provided useful input and corroborating information. ↑

- Hughes Opinion, cit., p.9, quoting Wilson Motion to Vacate, Ex.85.

-

Ibid., 6, See also Ex. 101 to Wilson Motion to Vacate (an exhibit copy was courteously provided to the author by Attorney Adler).

-

Ibid., 17. Also see Government Appendix, Ex. A (shared with the author by attorney Adler)

-

Adler confirmed this crucial point to the author as the correct interpretation of the CIA records cited by Judge Hughes. ↑

-

Hughes Opinion, cit., 11 and 20. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Denis Voltaire is a researcher from France who has studied and worked in Washington, D.C.

[…] https://covertactionmagazine.com/2023/10/27/notorious-secret-team-headed-by-cia-agent-theodore-shack… […]