“Frank Olson is flying and it’s a long way down” – David Clewell, “CIA in Wonderland.”

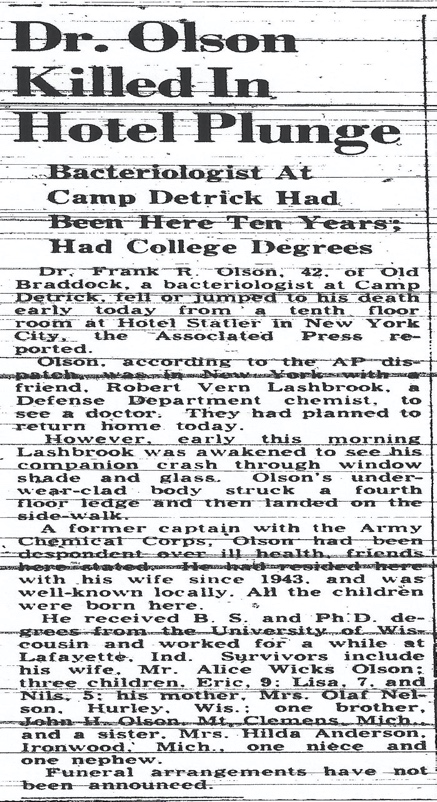

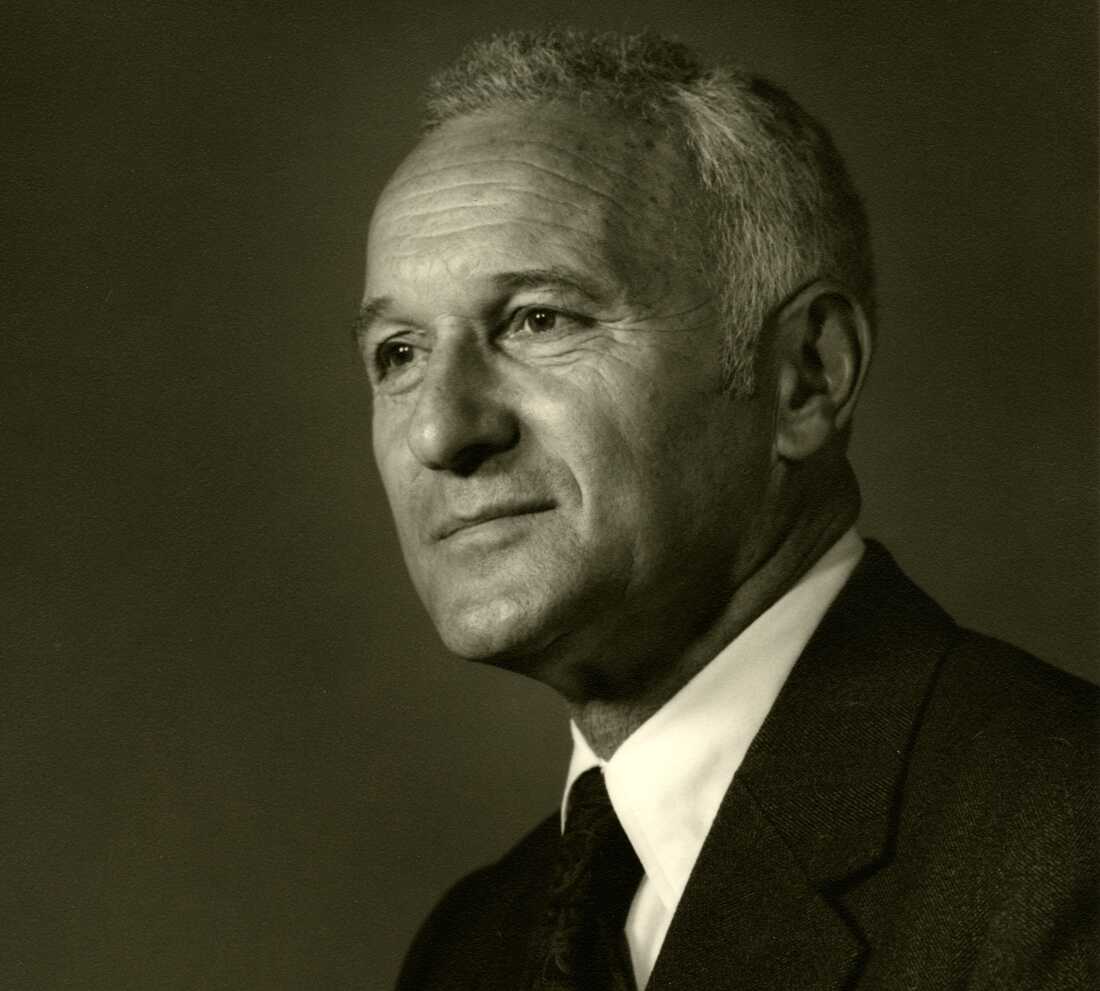

In September 1994, the NBC hit show Unsolved Mysteries aired an episode on Dr. Frank Olson, a CIA biochemist at the Fort Detrick laboratory on germ warfare. Olson had supposedly jumped to his death from the 13th floor of New York’s Statler Hotel on the night of November 28, 1953, after being unwittingly drugged with Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD).

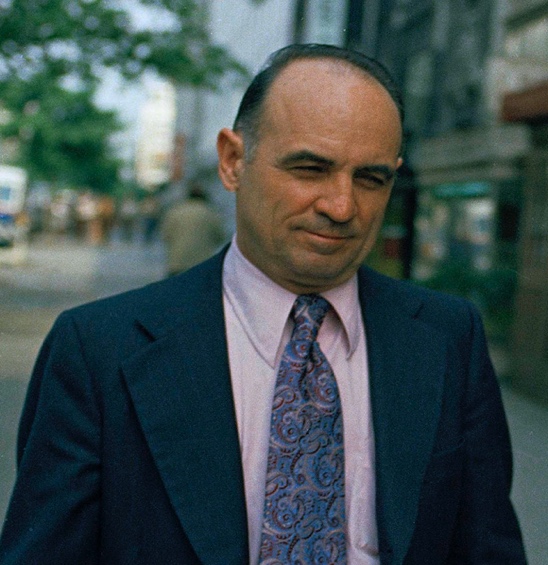

Host Robert Stack noted that certain facts, however, bred suspicion that Dr. Olson was murdered and that his murder was covered up. Strange was the behavior of Olson’s colleague Dr. Robert Lashbrook of the CIA’s Technical Services Division.

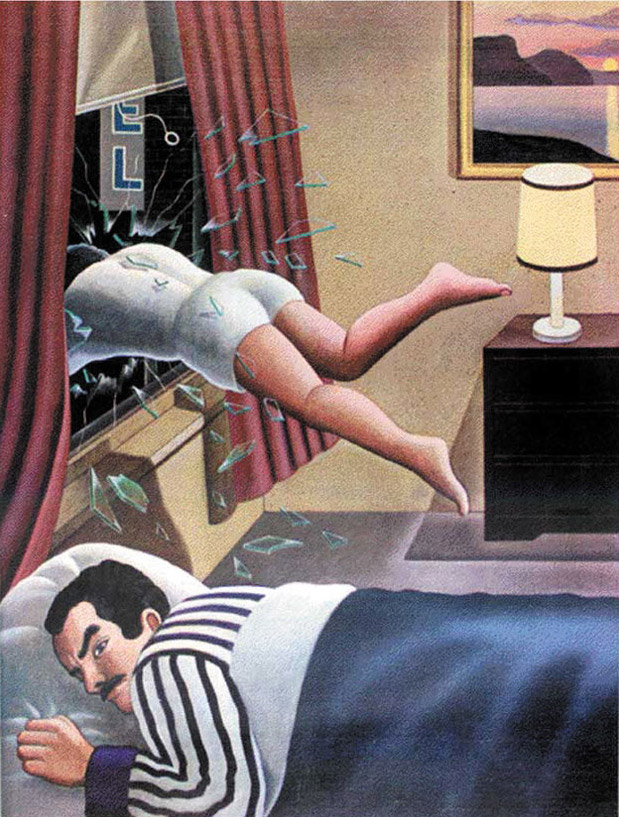

He could not recall whether the window was open or closed and did not leave the room after Olson allegedly jumped or call the police. Instead, Lashbrook made a manually recorded phone call to an unidentified source in which he said, “he’s gone.”

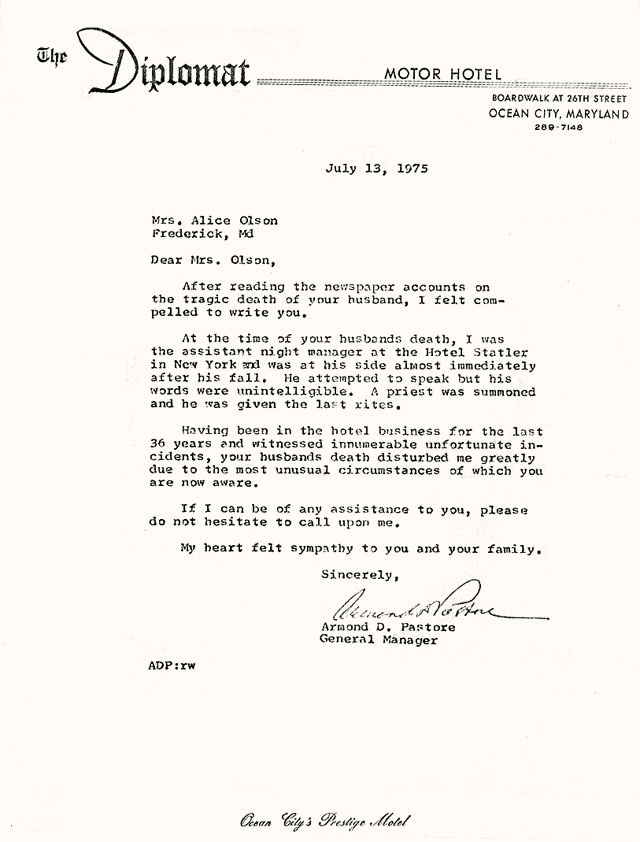

The person on the other end replied, “well that’s too bad,” and hung up. Hotel doorman Armond Pastore told Unsolved Mysteries that “nobody jumps through a window and dashes through the drape [as Olson was alleged to have done], there’s no sense to that.”

The crash from the window would have required a running start—which was impossible given the size of the room in which Olson was staying. The glass on the window was totally removed, which was also impossible if Olson had jumped through.

Olson’s bedsheet and clothes also had been pulled back in a manner consistent with someone ripping him out of bed forcibly.

Referencing Lashbrook’s suspicious phone call, Pastore told Unsolved Mysteries that it “was Hamlet who said ‘there’s something rotten in Denmark’…It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that there was something rotten at the Pennsylvania hotel [then called Statler] in New York that night.”[1]

Secret Government Experiments

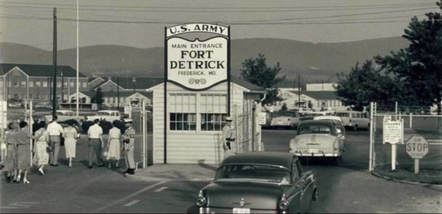

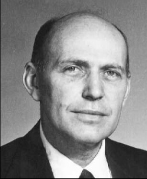

Born in rural Wisconsin in 1910, Frank Olson was a scientist at the Army Biological Warfare Center at Fort Detrick, Maryland.

He was involved with secretive government experiments in drug testing and chemical and biological warfare and the behavioral sciences during the early years of the Cold War.

In 1950, Olson became chief of the plans and operations branch of the CIA’s Special Operations Division (SOD) which connected him with Lashbrook.[2]

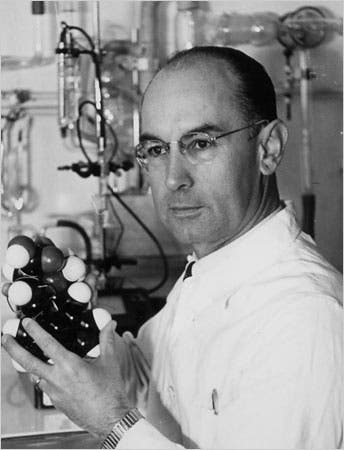

In that capacity, he served as a deputy to Dr. Sidney Gottlieb, who headed MK-ULTRA (CIA drug testing program).[3]

Working out of laboratories patrolled by armed guards with orders to shoot any intruders, the SOD grew lethal cells and cultured deadly viruses along with “techniques for the offensive use of biological weapons,” according to court documents, and “covert dissemination of biological warfare agents.”[4]

In the years leading up to his death, Olson reportedly visited France, Germany, England, and Norway, where an anonymous Fort Detrick employee said his work “may have been connected to the testing of psychoactive drugs.”

On June 12, 1953, declassified documents show that Olson arrived at Frankfurt from the Hendon military airport in England and made the short drive west into Oberursel.

There Artichoke experiments were taking place at a Safe House called Haus Waldorf.

“Between 4 June 1953 and 18 June 1953, an IS&O [CIA Inspection and Security Office] team…applied Artichoke techniques to operational cases in a safe house,” explains an Artichoke memorandum, written for CIA Director Allen Dulles, and one of the few action memos on record not destroyed by Richard Helms when he was CIA director.

The two individuals being interrogated at the Camp King safe house “could be classed as experienced, professional type agents and suspected of working for Soviet Intelligence. In the first case, light dosages of drugs coupled with hypnosis were used to induce a complete hypnotic trance,” the memo reveals. “This trance was held for approximately one hour and forty minutes of interrogation with a subsequent total amnesia produced.”[5]

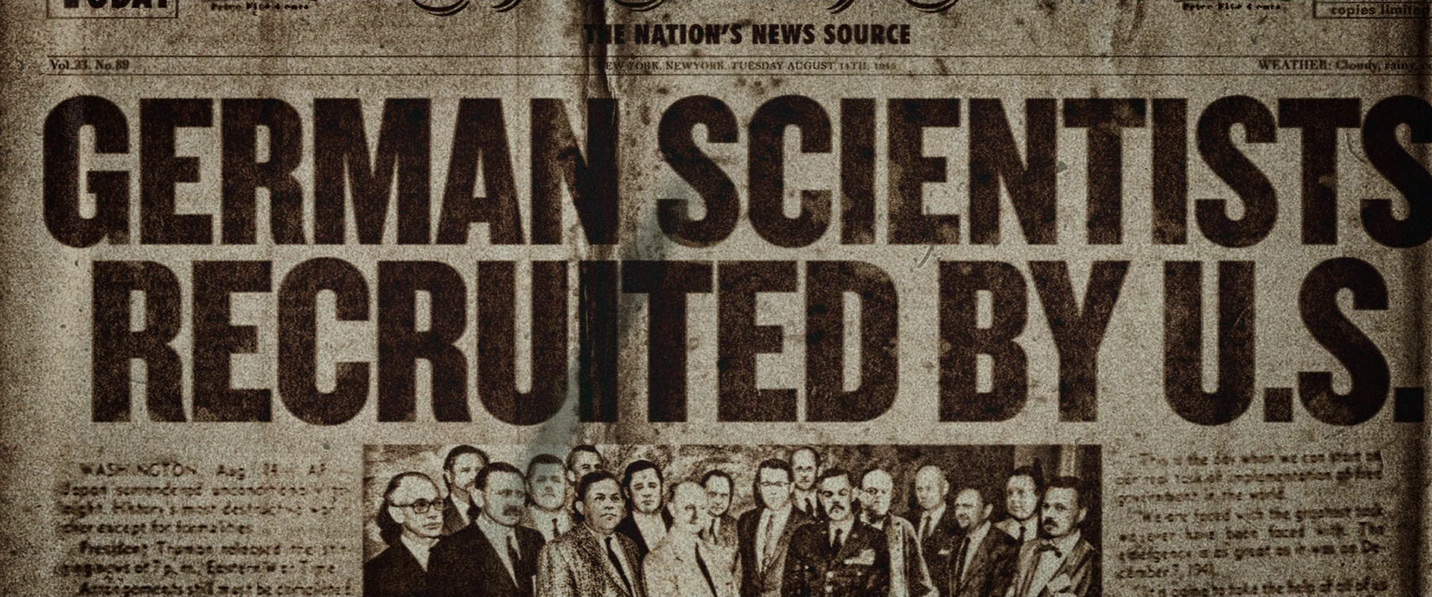

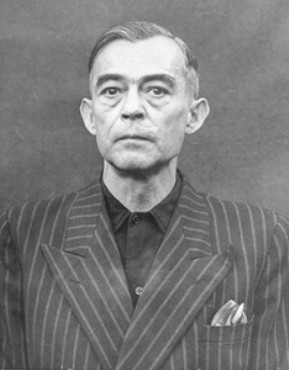

Through his work with SOD, Olson learned about the recruitment of Nazi scientists under Operation Paperclip.

Olson was allegedly among a secret group of Fort Detrick scientists who interviewed Dr. Walter Schreiber, the Nazi’s anthrax expert who tested psycho-chemical drugs on concentration camp inmates, and may have witnessed Dr. Kurt Blome, the Deputy Surgeon General of the Third Reich, conduct interrogation experiments at Camp King.[6]

According to his Fort Detrick colleague Norman Cornoyer, Olson had a “tough time after Germany….[d]rugs, torture, brainwashing,”[7] Cournoyer explained decades later for a documentary for German television made in 2001. Cournoyer said Olson felt ashamed about what he had witnessed, and that the experiments at Camp King reminded him of what had been done to people in concentration camps.

A Terrible Mistake

Back in the CIA’s office at Detrick Building Number 439, Olson contemplated leaving his job, telling his wife, Alice, that he had “made a terrible mistake.” Although we do not know exactly what he meant, Dr. Olson appears to have recognized he had placed himself in danger by admitting under interrogation that he had breached security protocols.

CIA consultant Stanley Lovell referred to Olson as “having no inhibitions. Baring of inner man,” meaning he had wrongly spoken out.[8]

William Sargant, a psychiatrist who advised British intelligence, reported that Olson was a security risk after he had expressed misgivings about his work with Artichoke to him.

The CIA subsequently placed a memo in his file claiming he may have violated security restrictions, which his sons believe led to his murder.[9]

“Key to Your Father’s Death”: Korea and Germ Warfare

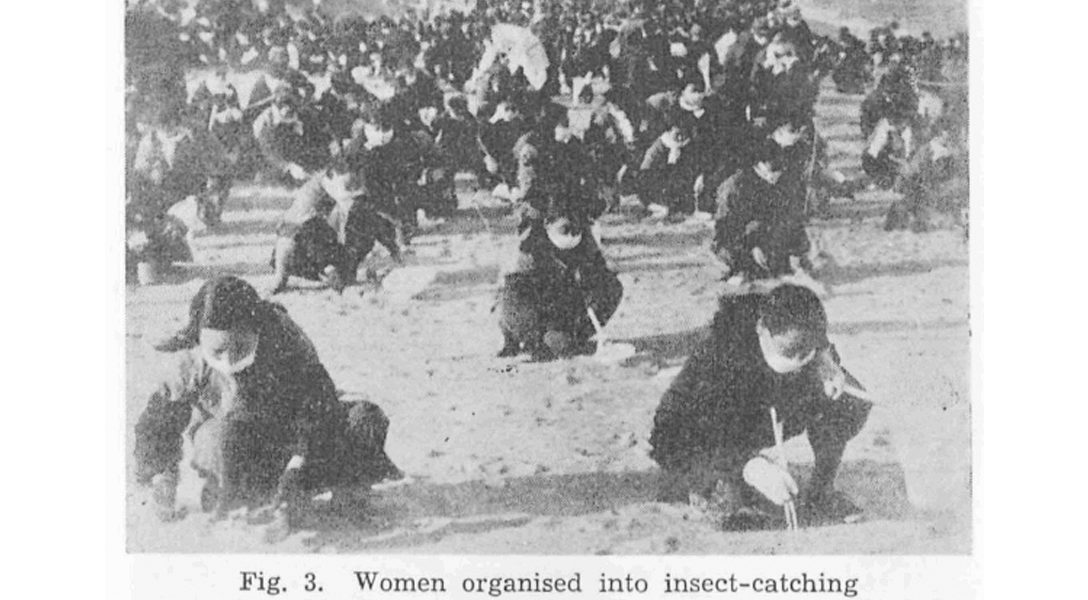

Alice Olson told her kids before her death in 1994 that “Korea really bothered your father.”[10] She was likely referring to his role in germ warfare experiments, which were part of an attempt to create a contamination belt designed to stop the movement of soldiers and supplies across the 38th parallel dividing North and South.[11]

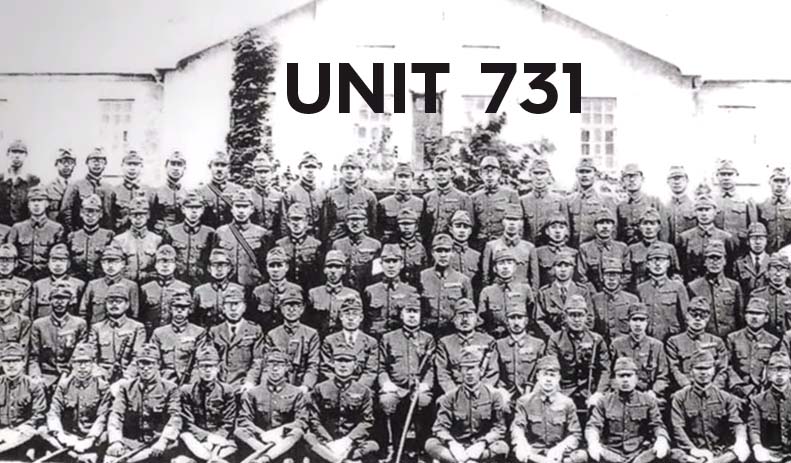

Olson and his colleagues at Fort Detrick had developed a capacity for producing and delivering bacteriological weapons through expertise acquired secretly from Japanese scientists such as General Shiro Ishii who, according to Reuters, visited South Korea during the Korean War.[12]

Members of his Unit 731—which carried out ghastly experiments in China during World War II—worked for a chemical section of a clandestine unit hidden in Yokosuke naval base during the Korean War, according to a 2001 Japanese language book.[13]

According to Professor Masataka Mori who has studied Unit 731, there are striking similarities between the diseases and weapons used by the Japanese military in China and those said to have been deployed by the United States against targets in northern Korea. “The bombs found on the Korean Peninsula were made of metal, while those used in China were ceramic,” Mori stated, “but the symptoms reported in North Korea are very similar to those witnessed in China.[14]

British author Gordon Thomas reported that Sidney Gottlieb instructed CIA agent Hans Tofte to obtain a selection of Korea’s insect life and small field animals like jungle rats and voles. These were brought back to Fort Detrick where Olson and the other “madmen in the laboratories” tested them on guinea pigs, rabbits, rhesus monkeys, and pigs in order to establish their suitability to form the basis for biological weapons.[15]

Olson is alleged to have subsequently traveled with Dr. Gottlieb to Tokyo to visit the Far East Command’s Unit 406 Medical Laboratory in the Mitsubishi Higashi building where researchers assisted by Japanese scientists were working with plague, anthrax, undulant fever, and cholera to discover their potential for being used as weapons.

Olson, according to Thomas, helped set up an ultra-high security unit known as 8003 that was active in the development of airborne pathogens.[16]

In 2019, the CIA proved that it had been lying to the public for decades about germ warfare in Korea when it released a trove of signals intelligence documents in a publication called Baptism by Fire: CIA Analysis of the Korean War.

The documents detail communications from CIA listening posts around the world that narrate the People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) of China and the North Korean People’s Army (KFA) responses to U.S. biological warfare (BW) attacks by airplane in North Korea from May 1951 through July 1953.

The communications include discussions of requests from field commanders to headquarters for instructions, back-up support, DDT (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and additional provisions to protect the local population from BW attacks that were designed to spread bubonic plague and other diseases.

Norman Cornoyer told Eric Olson—Frank’s son—in May 2001 that, “if biological warfare was used in Korea [which we know it was] your father definitely would have known it. Being in special operations at Detrick…oh yes, he would have known it.” Cournoyer stated further that Korea was “the key to your father’s death. It was where the two secret CIA programs—mind control experiments and the use of biological weapons—came together.”[17]

St. Anthony’s Fire: The CIA, LSD and the Pont-Saint-Esprit Plague

Hal Albarelli, Jr., author of the deeply researched book A Terrible Mistake, believes that Olson’s threatened whistleblowing centered on unethical CIA mind-control and drug experimentation and the agency’s connection to the outbreak of a mysterious plague in the southern French town of Pont-Saint-Esprit on August 16, 1951.[18]

On that day, 250 townspeople suddenly became wildly disoriented, babbling incoherently while mired in hallucinations.

Seven died from the outbreak including a twenty five-year-old man previously in good health, and many more had to be institutionalized.

At the time, people believed the bread had been poisoned with ergot by mold on some of its grains as in medieval plagues known as St. Anthony’s Fire, or that the water supply had somehow been contaminated.

Reviewing the first book-length account of the disaster, St. Anthony’s Fire by American journalist John Fuller in the British Medical Journal, author Griffith Edwards noted, “The official explanation [of the outbreak] was of flour having been contaminated by an organic mercury fungicide but much of the evidence points to a variety of ergot poisoning. The similarity of the symptoms to those of LSD effects is startling.”[19]

Fuller’s book noted the presence of Sandoz Company researcher Dr. Albert Hoffmann in Pont-Saint-Esprit during the summer of 1951 (Sandoz supplied LSD to the U.S. Army and CIA).[20]

Evidence from Frank Olson’s passport and those of his SOD colleagues shows that they happened to be in France at that time as well.

George H. White referred to the “secret” of Pont-Saint-Esprit in an agency memo; other declassified documents show that Sandoz and CIA officials engaged in discreet, ongoing discussions about Pont-Saint-Esprit which was referred to as “an experiment” and not an accident.

According to Albarelli Jr., the village was chosen because it was on the outs with the French government of Charles De Gaulle and had a number of communists living there.[21]

The U.S. Army at the time considered LSD a potential secret weapon that, when added to the drinking water, could make an army of soldiers disoriented and psychotic, hence incapable of fighting.

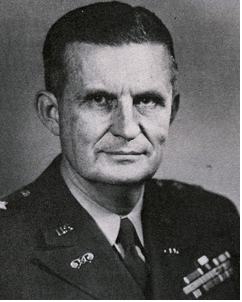

Major General William M. Creasy, former chief of the Army Chemical Corps, wrote in Reader’s Digest in September 1959, that psycho-chemical agents were preferable to conventional bombing to recapture [enemy-held] positions and could deliver a town unharmed “once the population has recovered from a brief period of lunacy.”[22]

The Army, Creasy said, had the capacity to deliver psycho-chemicals through aerosol bombs [Olson’s specialty] or in liquid and powder form by “sabotage methods” such as contamination of water and food supplies, which could have been tested at Pont-Saint-Esprit.

Albarelli Jr. found a secret FBI document that pointed to an experiment involving chemical agents that was planned for the New York subway system, and was told by a former Fort Detrick biochemist that the New York City experiments “were delayed until after the experiment was conducted in France.”

The results of the latter, he said, were “good” but yielded “an adverse effect or what would now be called a ‘black swan’ reaction. That several people died was unexpected, completely unexpected. It wasn’t supposed to turn out that way.”

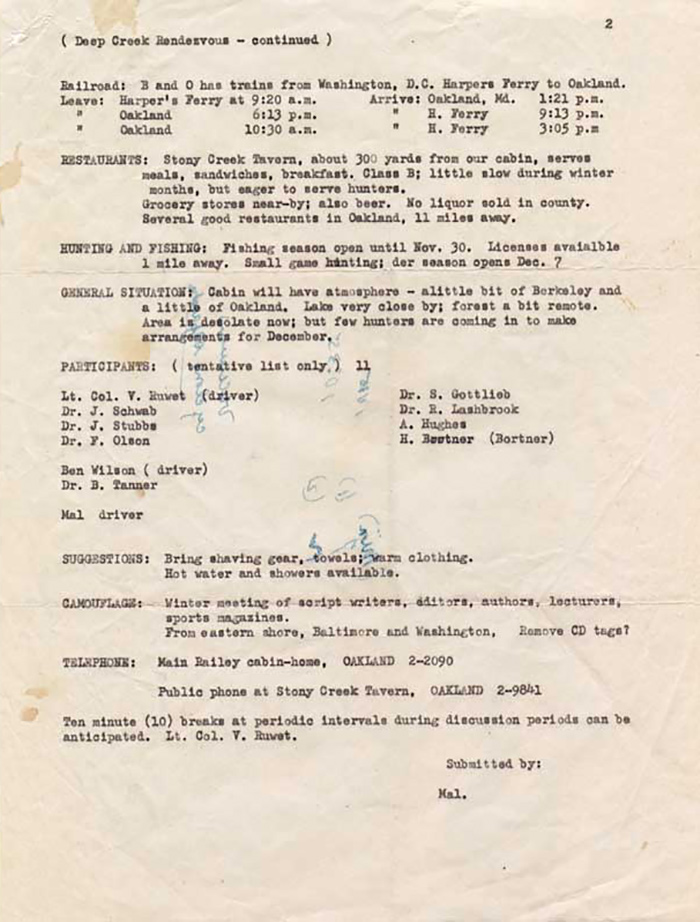

The same source told Albarelli Jr. that Olson was drugged at a company retreat in Deep Creek Lodge in Maryland several days before his death because he was thought to be “talking to the wrong people” about Pont-Saint-Esprit including a neighbor he carpooled with, and the CIA wanted to know the extent of his indiscretions.[23]

Olson feared for his safety on the eve of his death, telling his wife someone was trying to poison him. Before being checked into the Statler Hotel, he was taken to his old boss, Dr. Harold Abramson, because the two men knew each other well and it was thought Olson would be forthcoming about the reasons for his security breaches, but to no avail.[24]

Cover-up

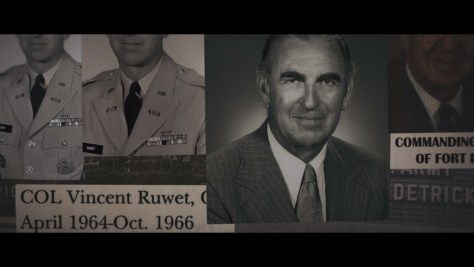

After Frank Olson’s death, his wife Alice was visited by Frank’s superior, Lt. Col. Vincent Ruwet who said that there had been “some sort of accident” and that Frank had “either fallen or jumped out of a window,” two very different things.[25]

The police investigation ended abruptly, and no autopsy was ever ordered. The priest called to administer Frank’s last rites was quietly moved aside. The family was told that Frank’s body was too badly disfigured for viewing—a falsehood that prevented the family from noticing a hematoma on his temple, a wound consistent with a blow to the head omitted from the 1953 medical examiner’s report.

Five CIA “investigators” carried out their own inquiry into what agency documents labelled a “suicide,” paying substantial sums to Dr. Harold Abramson and another unidentified colleague who knew the truth.[26] One of the CIA men, James McCord, was later involved in Watergate.

Robert Lashbrook and Sidney Gottlieb came over to the Olson home after the funeral and Vincent Ruwet made regular visits to “encourage [Alice] to think things that were not true about Frank’s death,” as he put it.[27]

In June 1975, the Rockefeller Commission, which was created to investigate CIA misdeeds, advanced the theory that Olson’s death resulted from an adverse reaction to LSD. The Olson family met with CIA Director William Colby and President Gerald Ford who released some pertinent documents, issued a formal apology, and awarded the family a $750,000 settlement.

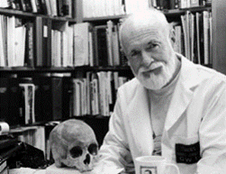

However, after the death of Frank’s widow, Alice, son Eric had Frank’s body exhumed and then examined by pathologist Dr. James E. Starrs from Georgetown University, who found a hole in Frank’s head that came from the butt of a gun and not a fall from a thirteenth-floor window.

The New York District Attorney subsequently changed the designation of Frank’s death from “suicide” to “unknown.”

Starrs’s autopsy had also revealed a lack of cuts or lacerations, which meant he had to have gone out of an open window as glass from the window would have cut his skin.

LSD furthermore was not conclusively found to be in his system.[28]

According to two confidential CIA sources interviewed by H.P. Albarelli Jr., when a late-night attempt was made to remove a subdued Olson from his room in the Statler to transport him by automobile to Maryland, “things went drastically wrong. The short and entire explanation is that [Olson] resisted and in the ensuing struggle he was pitched through the closed window.”

These same sources note that Lashbrook apparently was awake the whole time, though out of the way. They said that Olson was not “cut out for the type of work he was doing. He was in way over his head, and he knew it at last.”[29]

Shakespearian Tragedy

Errol Morris’s 2017 film, Wormwood, chronicles the Shakespearian tragedy in which Frank’s son Eric gives up a promising career as a psychiatrist to pursue the truth about his father’s death.

At the end, he comes close to uncovering the identity of the killers, though Seymour Hersh will not reveal his “deep throat” source.

Olson’s killing had major significance at the time in preventing disclosure of criminal CIA operations in the early Cold War.

In a press conference in August 2002, Eric Olson told the media that his father’s coffin had “turned out to be a pandora’s box. It’s no surprise that the CIA’s unethical human experiments would turn out to be linked to assassination. Once the value of human life has been cheapened, then murder lurks just around the corner.”[30]

Continued Fascination

That the American public has remained fascinated with the Olson case 70 years later reflects a deep-seated mistrust in government institutions.

American national identity has long been predicated, and the pursuit of overseas empire legitimated, on the belief that the U.S. democratic system is morally virtuous compared to illiberal rivals like China and Russia and that agents of the government would never kill their own citizens like in those nations.

The Olson case suggests that we are not who we say we are, and have no legitimacy in colonizing the globe with military bases.

This is why the case is so explosive and why, beyond the protection of individual reputations, there remains so much secrecy and resistance to a full accounting of the facts.

*This article is a shortened version of one that originally appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of Class, Race and Corporate Power. It was first published in CovertAction Magazine two years ago.

-

Unsolved Mysteries, September 27, 1994, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0737575/. ↑

-

H.P. Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake: The Murder of Frank Olson and the CIA’s Secret Cold War Experiments (Walterville, OR: Trine Day, 2009); Gordon Thomas, Secrets & Lies: A History of CIA Torture and Bio-Weapon Experiments (Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 2007). ↑

-

On Gottlieb’s career, see Stephen Kinzer, Poisoner In Chief: Sidney Gottlieb and the CIA Search for Mind Control (New York: Henry Holt, 2019). ↑

-

Eric Olson and Nils Olson v. United States of America, Civil Action No. 12-1924, Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Points and Authorities, May 3, 2013; Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake, 68. ↑

-

Annie Jacobsen, Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program That Brought Nazi Scientists to America (Boston: Little & Brown, 2015), 367. ↑

-

Jacobsen, Operation Paperclip; Jeffrey Steinberg, “It Didn’t Start with Abu Ghraib: Dick Cheney-Vice President for Torture and War,” Executive Intelligence Review, November 11, 2005, http://www.frankolsonproject.org/Articles/Steinberg-Cheney.pdf. Under a secret program called Dustbin, Blome, who had overseen medical experimentation at Dachau, had been hired to teach Americans interrogation methods. ↑

-

Thomas, Secrets & Lies. ↑

-

Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake; Jacobsen, Operation Paperclip, 369. ↑

-

Tom Schoenberg, “Six Decade Old Murder Subject of CIA Lawsuit,” December 2, 2012, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, http://www.post-gazette.com/business/legal/2012/12/03/Six-decade-old-murder-subject-of-CIA- lawsuit/stories/201212030192; Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake; Kinzer, Poisoner In Chief, 117. ↑

-

James Risen, “Suit Planned Over Death of Man CIA Drugged,” The New York Times, November 26, 2012. ↑

-

On the use of germ warfare in Korea, See Dave Chaddock, This Must Be the Place: How the U.S. Waged Germ Warfare in the Korean War and Denied It Ever Since (Seattle: Bennett & Hastings Publishers, 2013); Thomas Powell, “Biological Warfare in the Korean War: Allegations and Cover-Up,” Socialism and Democracy, 31, 1 (2017), 23-42. ↑

-

Jeffrey A. Lockwood, Six-Legged Soldiers: Using Insects as Weapons of War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 126, 172; Ed Regis, The Biology of Doom: America’s Secret Germ Warfare Projects (New York: Henry Holt, 2000), 110, 128; Sheldon H. Harris, Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932-1945, and the American Cover-Up, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2002). ↑

-

Ban Shigeo, Rikugun Noborito Kenkyujo no shinjitsu [The Truth About the Army Noborito Research Institute], Tokyo: Fuyo Shobo Shuppan, 2001, reviewed by Stephen C. Mercado on CIA website, https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi- studies/studies/vol46no4/article11.html ↑

-

Julian Royall, “Did the US Wage Germ Warfare in Korea?” The Telegraph, June 10, 2010. See also Stephen Endicott and Edward Hagerman, The United States and Biological Warfare: Secrets from the Early Cold War (Indiana University Press, 1999). ↑

-

Thomas, Secrets & Lies, 48. ↑

-

Thomas, Secrets & Lies; Wilfred G. Burchett and Alan Winnington, Koje Unscreened (Chinese-American Friendship Association, 1952), www.revolutionarydemocracy.org/archive/koje.pdf. ↑

-

Thomas, Secrets & Lies, 18; Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake, 679. ↑

-

Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake, 350; John G. Fuller, The Day of St. Anthony’s Fire (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1968). ↑

-

Griffith Edwards, “Poison in Pont-St.-Esprit,” British Medical Journal, May 3, 1969, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1983173/pdf/brmedj02030-0064a.pdf; Fuller, St. Anthony’s Fire, 301. ↑

-

Hoffman mentions the outbreak in his own book, LSD: My Problem Child, in 1979, but leaves out that he was in town in the days immediately after. ↑

-

Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake, 350; “Behind the Headlines: Hank Albarelli Interview,” July 28, 2013, https://www.sott.net/article/264434-Behind-the-Headlines-Hank-Albarelli-Interview-CIA-Mind-Control-Frank- Olson-and-JFK. ↑

-

William M. Creasy, “Can We Have War Without Death?” Reader’s Digest, September 1959, 73-76 ↑

-

Olson was thus a target of enhanced interrogation. ↑

-

Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake, 689-691. After watching a film about Martin Luther, Olson went into work to tender his resignation; however, he was instead taken by Lashbrook to the house of a former Broadway magician John Mulholland who probably hypnotized him, and Frank again revealed his intentions to blow the whistle. ↑

-

Frank’s obituary in The Washington Star also proclaimed that Olson had either fallen or jumped to his death and noted that Frank was found in his underwear and had crashed through the window. However, falling and crashing through a window are two separate things. ↑

-

Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake, 34, 35; James E. Starrs and Katherine Ramsland, A Voice for the Dead: A Forensic Investigator’s Pursuit of the Truth in the Grave (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2005), 131, 148; Eric Olson and Nils Olson v. United States of America, Civil Action No. 12-1924, Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Points and Authorities, May 3, 2013; Kinzer, Poisoner In Chief, 124. James McCord, a former FBI intelligence agent and future Watergate burglar, according to journalist Stephen Kinzer, visited the room to assist Lashbrook in the cover-up. His specialty was making police investigations evaporate. ↑

-

Eric Olson and Nils Olson v. United States of America, Civil Action No. 12-1924, Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Points and Authorities, May 3, 2013. ↑

-

Starrs and Ramsland, A Voice for the Dead, 131, 148. ↑

-

Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake, 693, 694. ↑

-

Albarelli Jr., A Terrible Mistake, 699. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.

The CIA murder of Frank Olsen is yet another illustration of the longstanding corruption of U.S. government agencies and how these agencies after having become infected by those individuals of a sociopathic paranoid mindset are now the source of the infection itself. When is it that the man no longer corrupts the institution but the institution begins to corrupt the man.