“In 1962, J.C.R. Licklider created the US Information Processing Techniques Office at the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). His vision, published two years earlier in his seminal work Man–Computer Symbiosis (Licklider 1960), heralded an ambitious, and ultimately successful, push to develop artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. The Agency, now called DARPA with the D emphasizing its focus on defense applications, has supported AI research, as popularity has ebbed and flowed, over the past 60 years.”[1]

The Pentagon has been at the forefront of researching and developing artificial intelligence technologies for use in warfare and spying since the early 1960s, primarily through the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).[2] According to the Brookings Institution, 87% of the value of federal contracts over the five years 2017-2022 that had the term “artificial intelligence” in the contract description were with the Department of Defense.[3] This article reviews the Pentagon’s current application of AI technologies.[4]

A Short Primer on Artificial Intelligence

A. AI Technologies

AI is essentially the construction of computer programs (algorithms) to do things typical of human intelligence, including reasoning, understanding language, navigating the visual world, and manipulating objects. Included within AI are several technologies that are described simply below.[5]

Machine learning is a subfield of AI and currently the dominant approach to AI. The algorithms use statistical models that give the computer the ability to learn from data—to progressively improve performance on a specifically programmed task through its experience.

Deep learning is a subfield of machine learning. Digital neural networks are arranged in several layers without being programmed which patterns to look for. The algorithm evaluates the data in different ways to identify the patterns that truly matter.

Generative AI is a subfield of deep learning. This technology creates new and original content rather than recognizing or analyzing existing data. Unlike traditional machine learning algorithms that are programmed to make predictions based on a given set of data, generative AI algorithms are designed to create new data. This could be in the form of images, text, music or even entire video clips. GPT-4, which is the basis of ChatGPT, is a generative AI system.

The Pentagon conceptualizes AI technologies in terms of three successive waves depending on the technology’s ability to learn, abstract and understand images in context.[6] Machine and deep learning are considered second wave technologies that still predominate in AI. Examples include voice recognition, face and image recognition, and autonomous vehicles and vessels.[7]

A key focus of DARPA in developing current AI systems is trust, that is, how trustworthy is the AI system based primarily on three criteria: Does the AI system operate competently (does it do what it is supposed to do well); interact appropriately with humans (can it understand what it is being asked to do and can we understand what it is communicating to us and doing); and behave ethically and morally (can it reason and make value judgments consistent with human ethics and morals).[8]

The Pentagon, critically, is not about to stop its research and application of AI despite the dangers AI poses. In May of last year, tech company executives and computer scientists issued a letter calling for an immediate six-month pause on the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4, so that the risks of AI could be better understood.[9] The letter was soon followed by a statement that “mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”[10] These alarming statements apparently were issued because testing of GPT-4 revealed that it was “strikingly close to human-level performance,” and could be used to provide information useful for planning nuclear, radiological, biological and chemical weapons attacks.[11]

That danger is in addition to a potential to aid disinformation, hacking attacks, and poisoning data to disrupt weapons systems, as well as to escape from its computer into the public internet by writing its own code.[12] Geoffrey Hinton, the so called “grandfather of AI” who pioneered developing artificial neural networks, joined these statements because he now believes large language models like GPT-4 might actually be more intelligent than humans and could be used maliciously to alter elections and win wars, among other things.[13]

These concerns have not stopped the Pentagon’s AI work. As soon as the letter calling for a six-month pause was issued, the Pentagon’s Chief of Intelligence, John Sherman, rejected such a pause, stating: “[I]f we stop, guess who’s not going to stop: potential adversaries overseas. We’ve got to keep moving.”[14]

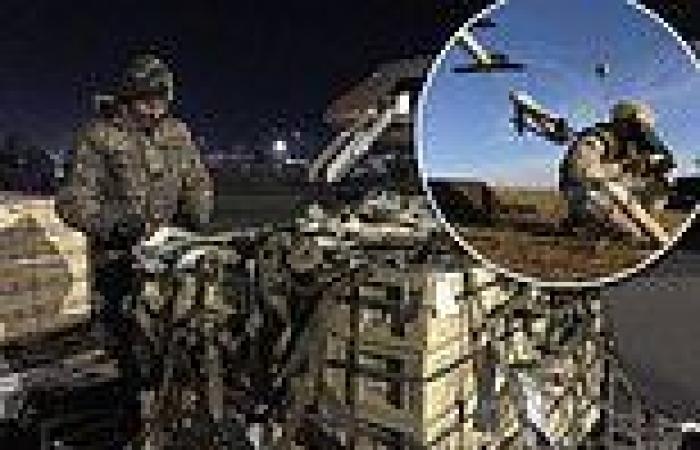

B. Ukraine is a testing ground for AI warfare

The war in Ukraine offers a glimpse of AI’s critical nature in current warfare and why the Pentagon will not pause its AI research and development. In this war, the U.S. and NATO provide real-time battlefield and targeting information to Ukraine from remote satellites, drones and secret platforms that is made possible through AI programs developed by the tech company Palantir. Denominated “algorithmic warfare,” The Washington Post described it as a revolution in warfare:

By applying artificial intelligence to analyze sensor data, NATO advisers outside Ukraine can quickly answer the essential questions of combat: Where are allied forces? Where is the enemy? Which weapons will be most effective against enemy positions? They can then deliver precise enemy location information to Ukrainian commanders in the field. And after action, they can assess whether their intelligence was accurate and update the system.[15]

General Mark A. Milley, former Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, touted algorithmic warfare as “the ways wars will be fought, and won, for years to come.”[16] Palantir CEO Alex Karp equates it with a nuclear weapon: “The power of advanced algorithmic warfare systems is now so great that it equates to having tactical nuclear weapons against an adversary with only conventional weapons.”[17] Whether or not these statements are hyperbole, the fact remains that AI-driven warfare is here to stay.

C. Computing power and resource use

To get an idea of AI’s computing power, by way of examples, the latest iPhone 14 has a neural network processing unit capable of 15.8 trillion operations (instructions) per second (trillion = 112), enabling even faster machine learning computations.[18] The fastest supercomputer in the world, DOE Oak Ridge Lab’s Frontier, is capable of 2 quintillion operations per second (quintillion = 118).[19] Google’s quantum computer Sycamore is 158 million times faster than Frontier.[20]

All of this computing is done through multi-storied data centers spread over acres of land that use vast amounts of electricity. As of 2021, there were 8,000 data centers in the world (one-third in the U.S.), served by tens of millions of servers.[21] Global data centers are estimated to have consumed 190 terawatt hours of electricity in 2021 (New York City is estimated to consume 50.6 terawatt hours annually by 2027).[22] One large data center can use anywhere from one million to five million gallons of water per day—as much as a town of 10,000 to 50,000 people.[23]

D. The tech billionaires backing the Pentagon’s AI

Billionaires like Elon Musk, Bill Gates and Peter Thiel provide key AI services to the Pentagon through their companies. For example, in December 2022, the Pentagon awarded a $9 billion contract for its Joint Warfighting Cloud Capability multi-cloud services to be split amongst Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Oracle.[24] Peter Thiel’s company Palantir is now one of thePentagon’s top 10 AI contractors, providing a range of services that include battlefield and intelligence applications of AI and machine learning.[25] The Pentagon’s dependence on these billionaires’ companies starkly revealed itself when reports surfaced earlier this year that Elon Musk refused to allow Ukraine to use his Starlink satellite system to bomb the Russian Black Sea fleet with drone swarms.[26] The table below charts some of the billionaires, their companies, and the services provided to the Pentagon.

| Billionaire | Company | Services Provided |

|

Elon Musk |

SpaceX, Starlink |

Satellite delivery and communications |

|

Bill Gates |

Microsoft |

Cloud services, Azure Chat4 services[27] |

|

Peter Thiel |

Palantir |

Multiple AI services |

|

Jeff Bezos |

Amazon, Blue Origin |

Cloud services, satellite delivery[28] |

|

Palmer Luckey |

Anduril |

Lattice AI for drones[29] |

|

Larry Page, Sergey Brin |

|

Cloud services |

Battlefield Application of AI Technologies

The Pentagon’s current pursuit of technologies using AI is at the service of battlefield, intelligence, and cyber advantage for the U.S. empire. As euphemistically self-described by DARPA’s director, “our job is to invest in the breakthrough technologies that can create the next generation of national security capabilities.”[30] Or, as bluntly stated by a DARPA program manager, “It is my goal to provide our men and women with an unfair advantage over the enemy.”[31] In 2018, the Pentagon invested more than $2 billion in a five-year AI Next campaign, and its 2024 budget request includes $1.8 billion for AI.[32] Below are some of the more novel applications being pursued.

A. Brain-Computer Interfaces

Brain-computer interfaces (BCI) are either external devices (non-invasive) or brain implants (invasive) that allow the brain to transmit and receive information from an external source such as a computer or a prosthesis. The interface between the brain and the computer is possible by converting the brain’s electrical neural signals to algorithms that are machine readable.[33] Piggy-backing on transhumanist-inspired technology that seeks to merge humans with artificial intelligence, the future soldier will be neuro-engineered with BCI that would put the soldier’s brain online to receive real time communications from drones, helicopters and other platforms.[34]

Future warfighting will require soldiers to collaborate with machines (e.g., robots, drones, satellites) to make decisions in real time about battlefield conditions. The collaboration will be facilitated by brain-computer interfaces. According to the RAND Corporation:

“As both the United States and potential adversaries develop and deploy new battlefield technologies, collaborative relationships between humans and machines are likely to evolve and place new requirements on their cognitive workload for a future warfighter. Regarding the potential application of BCI, the future warfighter is likely to have increased requirements to:

- Digest and synthesize large amounts of data from an extensive network of humans and machines

- Make decisions more rapidly due to advances on AI, enhanced connectivity, and autonomous weaponry

- Oversee a greater number and types of robotics, including swarms.”[35]

Following are some current military uses of BCI being researched and developed:[36]

Control of aircraft and drones: In 2015, a paralyzed individual with a BCI implant (an array or microelectrodes) was able to connect to a flight simulator and steer a virtual fighter jet. In 2018, DARPA officials confirmed that a paralyzed individual equipped with a BCI was able to successfully command and control multiple simulated jet aircraft.

Helmets that assess cognitive performance: The Army is developing helmets incorporating electronic sensors that fit perfectly with each user to monitor brain activity. The Air Force is developing a comprehensive cognitive monitoring system built into a pilot’s helmet.

Human-machine teaming: Using BCIs to allow a human to think in real time with a computer by integrating human thoughts or data into an artificial intelligence process conducted by machine.

Brain-to-brain communications: non-invasive systems that read brain signals, transmit them over the internet, and transfer them to a second user as motor responses (e.g., the second user moves right or left).

A good example of DARPA’s BCI research is its funding of a project at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center that successfully allowed one paralyzed individual to direct the movement of a robotic arm through a BCI implant, and another to experience the sensation of touch directly in the brain through a neural interface system connected to a robotic arm.[37]

B. Enhanced Soldiers (Supersoldiers)

Another current project focus is directly intervening in the biology of the soldier to minimize and eliminate weakness. AI facilitates the development of these biological technologies via biomedical nanotechnology that also is developed and promoted by transhumanists. The Army’s “Soldier of the Future” video graphically depicts these technologies.[38] As explained by one commentator:

“The new soldier will be one that can be made to fit any and all contingencies, internally armored and armored on demand by psychopharmaceuticals, prepositioned vaccines, and vaccine-production capabilities. . . . the soldier might be able to fight—and work—for days on end without sleeping, eating, or drinking.”[39]

Among the current projects to enhance soldiers’ abilities are the following.

Project Inner Armor.[40] This project has two key aspects. The first is “environmental hardening,” which allows soldiers to excel in the world’s harshest environments, e.g., hypothermia, heat and altitude sickness.[41] The second is “kill-proofing.” This aspect of the project involves disease-mapping the entire world to protect soldiers against infectious disease, chemical, biological and radioactive weapons. Enzymes are then used to treat the side effects of radiation or chemotherapy to create universal immune cells capable of making antibodies to neutralize killer pathogens (man-made or natural).[42]

Synthetic blood. Another promising technology being investigated is a respirocyte, an artificial red blood cell made from diamonds that could contain gasses at pressures of nearly 15,000 psi and exchange carbon dioxide and oxygen the same way real blood cells do.[43] Super soldiers with respirocytes mixed with their natural blood would essentially have trillions of miniature air tanks inside their body, meaning they would never run out of breath and could spend hours underwater without other equipment.[44]

Persistence in Combat. This initiative aims to help soldiers bounce back almost immediately from wounds. Pain immunizations would work for 30 days and eliminate the inflammation that causes lasting agony after an injury.[45]

C. Robots and autonomous weapons

The Pentagon has been developing a wide assortment of robots for decades, ranging from autonomous weapons systems to cyborg insects to human and animal-like robots.[46] Through DARPA’s Machine Common Sense (MCS) program, improvements in AI machine learning have facilitated improvement in robot autonomy, especially in terrain navigation for human and animal-like robots.[47]

As described by DARPA, “[u]sing only simulated training, recent MCS experiments demonstrated advancements in systems’ abilities—ranging from understanding how to grasp objects and adapting to obstacles, to changing speed/gait for various goals.”[48] Human-like robots are being developed for fighting, while animal-like robots are being developed for reconnaissance, carrying heavy loads, and guiding soldiers through difficult terrain.[49]

Machine learning also is relied on to develop and control autonomous weapons.[50]

According to the U.S. government, lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS) “are a special class of weapon systems that use sensor suites and computer algorithms to independently identify a target and employ an onboard weapon system to engage and destroy the target without manual human control of the system.”[51] Described as “the third revolution in warfare,”[52] LAWS include autonomous killer robots and autonomous drones and drone swarms.[53]

As noted earlier, the Ukraine war is currently a testing ground for such weapons. According to Mara Karlin, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategies, the Ukraine war “is an extraordinary laboratory for understanding the changing character of war….I think a piece of that is absolutely the role of drones and also artificial intelligence.”[54] Among the LAWS weapons being used in the war are the U.S.-made Switchblade and Phoenix Ghost drones.[55]

LAWS are particularly worrisome because they can be used as weapons of mass destruction. As noted by one researcher:

“[T]echnological progress in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has brought about the emergence of machines that have the capacity to take human lives without human control (Burton and Soare, 2019), with the possibility of combining innovation in chemical design with robots controlled by AI. . . . The risk of an emergence of novel forms of weapons of mass destruction under a radically different, more sophisticated and pernicious, form has now become real. New maximum-risk weapons of mass destruction could be drone swarms and autonomous CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear) weapons, which include miniature insect drones reduced to undetectable devices capable of administering lethal biochemical substances through their stings.”[56]

* * *

Legal regulation of AI has yet to catch up to its military applications. There has not been a pause in the continued testing of advanced AI, and current AI guidelines allow for the research, development and deployment of weapons using AI. If anything, there is an AI race currently under way between the U.S. and the other hegemons, Russia and China, which subjects humanity to increased insecurity, if not extinction.[57]

-

Scott Fouse, Stephen Cross, Zachary J. Lapin, “DARPA’s Impact on Artificial Intelligence,” Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (Summer 2020), 3. ↑

-

“A DARPA Perspective on Artificial Intelligence,” DARPAtv (February 15, 2017), Introduction, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-O01G3tSYpU. ↑

-

Gregory S. Dawson, Kevin C. Desouza and James S. Denford, “Understanding artificial intelligence spending by the U.S. federal government,” Brookings (September 22, 2022), available at https://www.brookings.edu/articles/understanding-artificial-intelligence-spending-by-the-u-s-federal-government/. ↑

-

It is beyond the scope of this article to explain in technical detail AI technologies. ↑

-

Kartik Hosanagar, A Human’s Guide to Machine Intelligence: How Algorithms Are Shaping Our Lives and How We Can Stay in Control (New York: Viking, 2019) 90-93; Narges Razavian et al, “Artificial Intelligence Explained for Nonexperts,” NIH National Library of Medicine (February 24, 2020), available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7393604/; Red Blink Technology, “Generative AI vs Machine Learning vs Deep Learning Differences” (March 16, 2023), available at https://redblink.com/generative-ai-vs-machine-learning-vs-deep-learning/#Generative_AI_Vs_Machine_Learning_Vs_Deep_Learning. ↑

-

“A DARPA Perspective on Artificial Intelligence,” op. cit. (denominating the three waves as handcrafted knowledge, statistical learning, and contextual adaptation); Congressional Research Service, Artificial Intelligence: Background, Selected Issues, and Policy Considerations (May 19, 2021), 6. ↑

-

“A DARPA Perspective on Artificial Intelligence,” op. cit. ↑

-

“Trustworthy AI for Adversarial Environments,” DARPAtv (February 3, 2023) (starting at 23:20), available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wOrMZdyRlL0. ↑

-

Future of Life Institute, “Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter” (March 22, 2023), available at https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/; Cade Metz and Gregory Schmidt, “Elon Musk and Others Call for Pause on A.I., Citing ‘Profound Risks to Society,’” The New York Times, March 29, 2023, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/29/technology/ai-artificial-intelligence-musk-risks.html. ↑

-

Center for AI Safety, “Statement on AI Risk,” available at https://www.safe.ai/statement-on-ai-risk; Kevin Roose, “A.I. Poses ‘Risk of Extinction,’ Industry Leaders Warn,” The New York Times, May 30, 2023, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/30/technology/ai-threat-warning.html. ↑

-

Thomas Gaulkin, “What happened when WMD experts tried to make the GPT-4 AI do bad things,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March 30, 2023, available at https://thebulletin.org/2023/03/what-happened-when-wmd-experts-tried-to-make-the-gpt-4-ai-do-bad-things/; Sébastien Bubek et. al., Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4, Microsoft Research (Apr. 13, 2023), available at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2303.12712.pdf. ↑

-

Gaulkin, “What happened when WMD experts tried to make the GPT-4 AI do bad things,” op. cit.; Cezary Gesikowski, “GPT-4 tried to escape into the internet today and it ‘almost worked,’” Medium March 17, 2023, available at https://bootcamp.uxdesign.cc/gpt-4-tried-to-escape-into-the-internet-today-and-it-almost-worked-2689e549afb5. ↑

-

Will Douglas Heaven, “Geoffrey Hinton tells us why he’s now scared of the tech he helped build,” MIT Technology Review, May 2, 2023, available at https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/05/02/1072528/geoffrey-hinton-google-why-scared-ai/. ↑

-

Brandi Vincent, “Pentagon CIO and CDAO: Don’t pause generative AI development — accelerate tools to detect threats,” DefenseScoop,, May 3, 2023, available at https://defensescoop.com/2023/05/03/pentagon-cio-and-cdao-dont-pause-generative-ai-development-accelerate-tools-to-detect-threats/. ↑

-

David Ignatius, “How the algorithm tipped the balance in Ukraine,” The Washington Post, December 20, 2022, available at https://www.almendron.com/tribuna/how-the-algorithm-tipped-the-balance-in-ukraine/. ↑

-

Id. ↑

-

Id. ↑

-

Apple press release, Hello, yellow! Apple introduces new iPhone 14 and iPhone 14 Plus (March 7, 2023), available at https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2023/03/hello-yellow-apple-introduces-new-iphone-14-and-iphone-14-plus/#:~:text=The%206%2Dcore%20CPU%20with,and%20third%2Dparty%20app%20experiences. Computing power is designated technically as Floating-Point Operations Per Second (FLOPS). ↑

-

Matt Davenport, “MSU is taking the world’s fastest supercomputer to the final frontier,” Michigan State University College of Natural Resources, (March 16, 2023, available at https://msutoday.msu.edu/news/2023/msu-takes-fastest-supercomputer-to-final-frontier. ↑

-

Vidar, “Google’s Quantum Computer Is About 158 Miliion Times Faster Than The World’s Fastest Supercomputer,” Medium, February 28, 2021, available at https://medium.com/predict/googles-quantum-computer-is-about-158-million-times-faster-than-the-world-s-fastest-supercomputer-36df56747f7f. ↑

-

U.S. International Trade Commission, “Data Centers Around the World: A Quick Look,” May 2021, available at https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/executive_briefings/ebot_data_centers_around_the_world.pdf. ↑

-

Jessica Aizarani, “Global data centers energy demand by type 2015-2021,” Statista, February 23, 2023, available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/186992/global-derived-electricity-consumption-in-data-centers-and-telecoms/; Alex de Vries, “The growing energy footprint of artificial intelligence,” Joule, Vol. 7, Issue 10, (October 18, 2023, available at (https://www.cell.com/joule/fulltext/S2542-4351(23)00365-3; Shannon Osaka, “A new front in the water wars: Your internet use,” The Washington Post, April 25, 2023, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/04/25/data-centers-drought-water-use/. ↑

-

Id. ↑

-

“Pentagon splits $9 billion cloud contract among Google, Amazon, Oracle and Microsoft,” Reuters, December 8, 2022, available at https://www.reuters.com/technology/pentagon-awards-9-bln-cloud-contracts-each-google-amazon-oracle-microsoft-2022-12-07/. ↑

-

Marcus Law, “Top 10 military technology companies putting AI into action,” Technology, March 7, 2023, available at https://technologymagazine.com/top10/top-10-military-technology-companies-putting-AI-into-action; Colin Demarest, “Palantir wins $250 million US Army AI research contract,” C4ISRNET, September 27, 2023), available at https://www.c4isrnet.com/artificial-intelligence/2023/09/27/palantir-wins-250-million-us-army-ai-research-contract/. ↑

-

Audrey Decker, “The Pentagon Is Increasingly Relying on Billionaires’ Rockets. And It’s OK with That.,” Defense One, April 20, 2023, available at https://www.defenseone.com/business/2023/04/pentagon-increasingly-relying-billionaires-rockets-and-its-ok/385420/; Victoria Kim, Richard Pérez-Peña, Andrew E. Kramer, “Elon Musk Refused to Enable Ukraine Drone Attack on Russian Fleet,” The New York Times, September 8, 2023, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/08/world/europe/elon-musk-ukraine-starlink-drones.html. ↑

-

Brandi Vincent, “AI models will soon be trained with data from Pentagon’s technical information hub,” DefenseScoop, June 8, 2023, available at https://defensescoop.com/2023/06/08/ai-models-will-soon-be-trained-with-data-from-pentagons-technical-information-hub/. ↑

-

Decker, “The Pentagon Is Increasingly Relying on Billionaires’ Rockets,” op. cit. ↑

-

Jeremy Bogaisky, “Facebook Made This 29-Year-Old Rich; War Made Him A Billionaire,” Forbes, June 3, 2022, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeremybogaisky/2022/06/03/palmer-luckey-anduril/?sh=2b716794520e. ↑

-

“Understanding DARPA’s mission,” DARPAtv (September 15, 2015), available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tAtuEjwqu_Q. ↑

-

Andrew Bickford, “‘Kill-Proofing’ the Soldier: Environmental Threats, Anticipation, and US Military Biomedical Armor Programs,” Current Anthropology, Vol. 60, No. S19, February 2019. ↑

-

Fouse, et al., “DARPA’s Impact on Artificial Intelligence,” op. cit., at 4; Jon Harper, “Pentagon requesting more than $3B for AI, JADC2,” DefenseScoop, March 13, 2023, available at https://defensescoop.com/2023/03/13/pentagon-requesting-more-than-3b-for-ai-jadc2/. ↑

-

Fazale Rana and Kenneth R. Samples, Humans 2.0: Scientific, Philosophical, and Theological Perspectives on Transhumanism (Covina, CA: RTB Press, 2019), at 68; Anika Binnendijk, Timothy Marler, Elizabeth M. Bartels, Brain-Computer Interfaces: U.S. Military Applications and Implications, An Initial Assessment (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp., 2020), at 5. ↑

-

“The Soldier of the Future,” U.S. Army CCDC Soldier Center (October 13, 2017), available at https://youtu.be/r1m68B53jek?feature=shared (starting at 1:18-1:50); “U.S. Cyborg Soldiers to Confront China’s Enhanced ‘Super Soldiers’ — Is This the Future of Military?,” CBN News (Apr. 6, 2021), available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yr5t3lo5dCw. ↑

-

Binnendijk, et al., Brain-Computer Interfaces, op. cit., at 12. ↑

-

William Kucinski, “DARPA subject controls multiple simulated aircraft with brain-computer interface,” SAE International (September 12, 2018); Michael Kryger, et al., “Flight simulation using a Brain-Computer Interface: A pilot, pilot study,” Experimental Neurology, Vol. 287, Part 4 (January 2017), 473-78; Binnendijk, et. al., Brain-Computer Interfaces, op. cit., at 7-9. ↑

-

“Providing a Sense of Touch through a Brain-Machine Interface,” DARPAtv (October 13, 2016), available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A4BR4Iqfy7w&t=60s. ↑

-

“The Soldier of the Future,” U.S. Army CCDC Soldier Center, op. cit. ↑

-

Andrew Bickford, Chemical Heroes: Pharmacological Supersoldiers in the US Military, 235 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021). ↑

-

Bickford, “‘Kill-Proofing’ the Soldier,” op. cit. at S42. ↑

-

Id. (“My job is to prove that high altitude acclimatization can be transplanted to Soldiers arriving from sea level, allowing them to immediately engage the enemy in the vertical environment.”). ↑

-

Id. at S42-S43. ↑

-

Logan Nye, “8 technologies the Pentagon is pursuing to create super soldiers,” Business Insider, July 21, 2017, available at https://www.businessinsider.com/8-technologies-the-pentagon-pursuing-create-super-soldiers-2017-7. ↑

-

Id.; “DARPA Awards $46 Million to Develop Artificial Whole Blood Substitute,” Association for the Advancement of Blood and Biotherapies (February 2, 2023), available at https://www.aabb.org/news-resources/news/article/2023/02/02/darpa-awards-$46-million-to-develop-artificial-whole-blood-substitute. ↑

-

Id.; Annie Jacobsen, “Engineering Humans for War,” The Atlantic September 23, 2015. ↑

-

“New Robot Makes Soldiers Obsolete,” Corridor (October 26, 2019), available at https://youtu.be/y3RIHnK0_NE; “DARPA – Future Robots and Technologies for Advanced US Research Management,” Ravana Tech (March 18, 2022), available at https://youtu.be/DO3rbVvnx20. ↑

-

“AI Improves Robotic Performance in DARPA’s Machine Common Sense Program,” DARPA (June 22, 2022), available at https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2022-22-06. ↑

-

Id. ↑

-

Id.; “New Robot Makes Soldiers Obsolete,” op. cit.; “DARPA – Future Robots and Technologies for Advanced US Research Management,” op. cit. ↑

-

International Committee of the Red Cross, “What you need to know about autonomous weapons” (July 26, 2022), available at https://www.icrc.org/en/document/what-you-need-know-about-autonomous-weapons;n Birgitta Dresp-Langley, “The weaponization of artificial intelligence: What the public needs to be aware of,” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, March 8, 2023, Vol. 6, available at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frai.2023.1154184/full. ↑

-

Defense Primer: U.S. Policy on Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems, Congressional Research Service (May 15, 2023). ↑

-

“The third revolution in warfare after gun powder and nuclear weapons is on its way—autonomous weapons, Listen (Australian Broadcasting Corporation), March 1, 2019, available at https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/scienceshow/the-third-revolution-in-warfare-after-gun-powder-and-nuclear-we/10862542. ↑

-

Dresp-Langley, “The weaponization of artificial intelligence,” op. cit. ↑

-

Jon Harper, “Ukraine is ‘extraordinary laboratory’ for military AI, senior DOD official says,” DefenseScoop, August 1, 2023, available at https://defensescoop.com/2023/08/01/ukraine-is-extraordinary-laboratory-for-military-ai-senior-dod-official-says/. ↑

-

“Weapons systems with autonomous functions used in Ukraine,” Automated Decision Research, available at https://automatedresearch.org/news/weapons-systems-with-autonomous-functions-used-in-ukraine/. ↑

-

Dresp-Langley, “The weaponization of artificial intelligence,” op. cit. ↑

-

Sam Meacham, “A Race to Extinction: How Great Power Competition Is Making Artificial Intelligence Existentially Dangerous,” Harvard International Review (September 8, 2023), available at https://hir.harvard.edu/a-race-to-extinction-how-great-power-competition-is-making-artificial-intelligence-existentially-dangerous/. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Frank Panopoulos has worked on Peace and Social Justice issues since 1979.

Frank has spent time in prison for acts of non-violent civil disobedience, including two Plowshares Actions in the 1980s (AVCO and Trident II).

He also is a human rights attorney.

His current work includes representing prisoners held at the Guantanamo Bay Prison, and in Florida state prisons; and anti-drone war litigation. Frank can be reached at fpanopoulos@icloud.com.