Huge Human Costs of Many of His Policies Go Ignored Along with Their Impact on the Global South

The passing of Henry Kissinger on November 29, 2023, has sparked an intense debate over the legacy of the controversial statesman, with the remarkable persistence of laudatory comments.

Echoing similar notes in mainstream media, George Beebe at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft went so far as to say that “Henry Kissinger’s impact on American foreign policy, although controversial, was on balance overwhelmingly positive.”

The achievements Kissinger is mostly recognized for, besides the negotiated cease-fire with South Vietnam in 1973, are “the opening to China; the detente with the Soviet Union and arms control; and the Middle East peace process, which goes back to the ’73 Yom Kippur War. Those are all masterful diplomatic strokes,” remarked Professor Joseph Nye in the commemoration hosted by The Harvard Gazette.

Historian Niall Ferguson had gone even further in his highly praised political biography of Kissinger’s early years, significantly titled “Kissinger: 1923-1968: The Idealist,” arguing that “the idea of Kissinger as the ruthless arch-realist is based on a profound misunderstanding.”1

To mark Kissinger’s passing, the National Security Archive of George Washington University, which has probably done more than anyone else to research and document Kissinger’s policies, has shared a trove of information, which strongly enhances our understanding of Kissinger’s legacy.

A sober look at the evidence shows that Kissinger’s record is not really so “controversial,” and it is certainly much darker than officially acknowledged. Kissinger’s praised achievements, when they were so in fact2, are irredeemably overshadowed by unjustifiable atrocities, which cost hundreds of thousands of lives across the world. When Kissinger did pursue a peace-leaning course of action, as finally in Vietnam, it was often out of political opportunism or after exhausting the most extreme warmongering options in the process.

Scholars who downplayed Kissinger’s criminal record forget his most blatant disregard for democracy and human cost of “realpolitik” in what today would be described as the “Global South” (although Kissinger was not particularly concerned about undermining democracy in Western-allied countries either). Countries such as Cambodia, Laos, Chile, Argentina or Bangladesh are still reeling from the consequences of Kissinger’s brutal policies, hardly enhancing the U.S. standing in the region.

The persistent understatement of Kissinger-backed atrocities in U.S. legacy media and academia also evidences structural problems in U.S. historiography and memory building, too frequently skewed against a proper acknowledgment of the huge human cost caused by U.S. foreign policy.

Reflecting on Henry Kissinger’s legacy is also a way to understand how the U.S. establishment continues to represent and interpret its own role in the world.

Probing Henry Kissinger

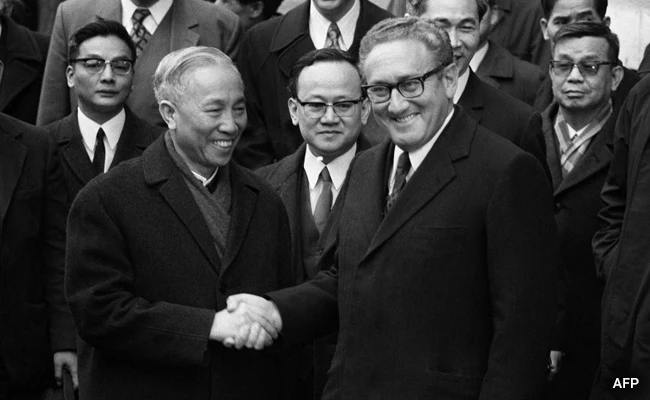

In one of its most contested decisions, the Nobel Committee awarded Kissinger and Vietnamese chief political adviser Le Duc Tho a joint Peace Prize for “having negotiated a cease-fire in Vietnam in 1973,” which may help to explain the enduring controversy over Kissinger’s legacy.3

Yet, it is a fact that Nixon and Kissinger negotiated peace only after unnecessarily prolonging the war for years, while conceiving the most inhumane policies to end it on their own terms. In October 1968, Nixon had even secretly attempted to sabotage President Johnson’s advanced negotiation effort to reach a settlement with Hanoi4, by relying in part on insider information provided by Kissinger, at the time foreign policy adviser in the Johnson administration, for the sole purpose of preventing a Democratic victory in the November election.

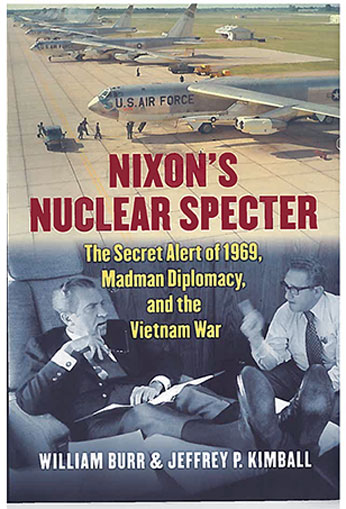

By 1969, therefore, there were already the conditions for peace with Vietnam, but Nixon and Kissinger pursued a different avenue. The so called “Madman diplomacy,” by which Nixon and Kissinger tried to persuade Hanoi and Moscow that Washington would go to any lengths to win the war, including resorting to nuclear weapons, in order to force North Vietnam to the negotiating table, did culminate in “a secret global nuclear alert in October” 1969, which could have easily spiraled out of control with potentially catastrophic consequences.5

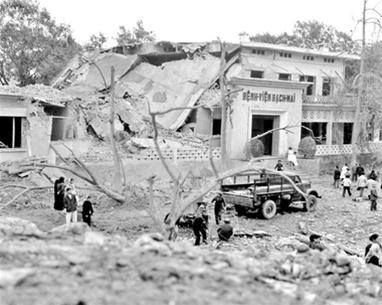

Toward that same end, Nixon and Kissinger also continued the extensive bombing of North Vietnam first perpetrated by the Johnson administration, which includes the infamous “Operation Linebacker II” of December 1972. Initiated on December 18, the “Christmas bombing” dropped more than 20,000 tons of explosives over 11 days, targeting mostly the heavily populated capital of Hanoi, including the city’s main hospital.6

The carpet bombing of neutral Cambodia, ordered by Nixon and Kissinger to stop “Vietnamese exfiltration,” may remain the most consequential, while still understated, criminal policy backed by Kissinger in Southeast Asia. Beginning in total secrecy in March 1969, the massive U.S. air campaign dropped more than 500,000 tons of bombs on Cambodia in the 1969-1973 period which, if one factors in the air campaign of the Johnson presidency, could have made Cambodia one of the most heavily bombed countries in history, according to Yale historian Ben Kiernan.

These figures make a mockery out of Kissinger’s repeated defense that the Cambodia operation was “selective” and strictly confined to trespassing Vietnamese troops. As recently as May 2023, an investigation from The Intercept exposed a high level cover-up to conceal the operation’s casualty rate, which was in the order of “as many as 150,000 civilians.” As Joseph Nye noted in The Harvard Gazette, the bombing campaign also fueled the takeover of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime, responsible for “the deaths of an estimated 1.7 million Cambodians.” Cambodia has never completely recovered from that tragedy.

Nixon and Kissinger also carried on the massive bombing of Laos started by the Johnson administration in 1964 to stem the Laotian communist insurgency of Pathet Lao, a group allied with North Vietnam and the Soviet Union, which lasted until 1973 and dropped a staggering two million tons of bombs on the country.7 In what is another largely forgotten humanitarian crisis, the unexploded cluster bombs continue to harm and haunt Laotians to this day.

It is very hard to see how this abysmal record could be described as rational and proportionate to the war effort in Southeast Asia, especially because it was directed at countries that did not represent a direct military threat to the U.S. territory or, like Cambodia, were not even party to the conflict. Not to mention the fact that the massive bombing campaign, as the Johnson years had already amply proven, far from stiffening the resolve of Vietnamese resistance, actually reinforced it and radicalized the anti-U.S. resentment even further, both in Vietnam and Cambodia.

The “China Opening”: Setting the record straight

Kissinger is frequently credited with the diplomatic “opening to China” in the early 1970s, which culminated in Nixon’s historic visit of February 1972, the first to Mainland China for a sitting U.S. president.

The China opening, its clear historical significance aside, also required “real moral courage on Kissinger’s part,” notes scholar Anatol Lieven, “given the forces arrayed against these policies in the United States.”

In truth, the same could be said about the negotiated cease-fire with Vietnam, which was also bitterly opposed by part of the U.S. power establishment. This point has merit, but it should be read much less as a warrant of Kissinger’s peace-seeking credentials than as a testament to the hyper-warmongering inclination of the U.S. establishment.8

However, Kissinger’s real role and motives in the China opening are frequently misrepresented.

First, the idea did not originate with Kissinger. That initiative, says Tom Blanton, Director of the National Security Archive, “turns out to be Mao’s idea with Nixon’s receptiveness, initially dissed by Kissinger.”9

The record also shows that the “China opening” was ambivalent and largely conceived to drive a wedge between Russia and China. The background of that diplomatic initiative was the imperative to deal with the catastrophic political consequences of the Vietnam war debacle, which was universally perceived as a “victory” for the communist world.

Even scholars who have expressed favorable views of Kissinger’s record, such as George Beebe or John Allen Gay from the John Quincy Adams Society, candidly concede that Kissinger saw the China opening as “an opportunity to exploit tensions between Moscow and Beijing,” with the ultimate aim to sow “division in the Communist world.”

This is not to deny that the China opening had positive effects and could actually set a good policy precedent for the U.S. today.

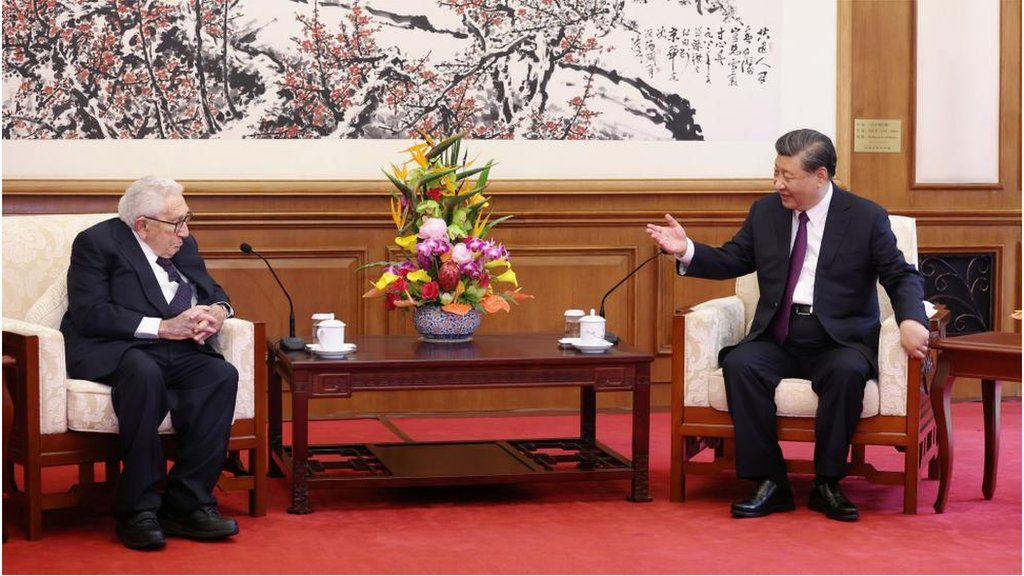

Not surprisingly, most Chinese leaders have actually mourned the death of Kissinger, who is perceived, in part wrongly, as the chief architect of the historic initiative. As the U.S. Institute of Peace notes, “for the Chinese, Kissinger is inseparable from what is widely viewed as a golden era in U.S.-China relations,” which admittedly is nowhere in sight in our times.

However, this cannot detract from the fact that Kissinger did not have the paternity of the China opening and that, in his mind, the destabilizing effect on geopolitical adversaries was the main goal.

What is absolutely certain is that the China opening, from Kissinger’s perspective, had nothing to do with promoting “peace” or, less than ever, with seeking more of an accommodating approach with the communist bloc.

Seeing red: Kissinger’s anti-communist obsession

The need to “contain communism,” exacerbated by the fall of Saigon in 1975, continued to govern Kissinger’s policies in the most extreme way, with total disregard for human cost, democratic standards, and regardless of the actual threat represented by communist parties around the world.

This rationale was particularly evident in Kissinger’s stance toward Latin America. As the South Vietnam effort against the Vietcong continued to deteriorate and then finally collapsed, Kissinger directed a sharp tightening of U.S. policy in South America, supporting coups d’état and the most brutal dictatorships, engaged in systematic repression and extermination of any perceived “leftist” opposition.

The U.S.-backed overthrow of democratically elected President Salvador Allende in Chile in September 1973 remains the most quoted case, for valid reasons, considering the extent of the Pinochet regime’s human rights violations.10

Largely underreported, however, are Kissinger’s role in the notorious “Operation Condor,” an international endeavor of Latin America’s Southern Cone dictatorships11 to track and kill “political dissidents” around the world, including citizens of allied countries like Italy, and his support to the military junta which took power in Argentina after the coup d’état of March 1976 and brutally ruled the country until 1983, engaging in a massive campaign of “disappearance” of domestic opponents.

The U.S. support to the Argentine junta’s “Dirty War” on internal dissent is still the subject of a complex process of reconstruction and reconciliation between Washington and Buenos Aires, which includes ongoing efforts of “declassification diplomacy.” The human toll was appalling, as Tom Blanton recalls, with about “30,000 Argentines disappeared by the junta with Kissinger’s green light.”

A fully documented episode is quite enlightening about Kissinger’s real priorities, as well as his completely disproportionate, out-of-touch-with-reality approach to the perceived threat of “leftist subversion.”

A State Department Telcon dated June 30, 1976, recorded a conversation where Kissinger scolds his aides after learning that the U.S. embassy in Buenos Aires had dared to issue a démarche to the Argentine military junta, due to the dreadful escalation of human rights violations ensuing after the coup d’état of 1976, which contradicted Kissinger’s directive of “full green light” to the new regime.

Clearly irritated, Kissinger asks State Department officer Harry Shlaudeman “In what way is it [the démarche] compatible with” his policy.

“It is not,” replied Shlaudeman, as Kissinger continued to challenge him:

“K: How did it happen?

S: I will make sure it doesn’t happen again.

K: If that doesn’t happen again something else will happen again. What do you guys think my policy is?

S: I know what your policy is, Sir. And will make sure they know too.

K: What can be done about this now?

S: Let me see if we can’t send a clarifying message.

K: You better be careful. I want to know who did this and consider having him transferred.”

In both Chile and Argentina, the military juntas had overthrown democratically elected governments and, while both countries were prey to widespread social unrest (in the case of Chile, in part at Washington’s instigation), the terrifying threat of a “communist takeover” was never convincingly proven.12

As CovertAction Magazine showed in covering the latest developments in the Aldo Moro affair, Kissinger actually had no qualms in supporting the most radical actions even in closely allied democracies like Italy, a NATO member, where communist parties were elected legally, fully integrated in the political process and had already accepted the Atlantic affiliation of the country.

It is exceedingly difficult to warrant Kissinger’s policies in Latin America with any legitimate aim to contain communism, which was frequently completely overblown or grossly exaggerated anyway.

It is even harder to reconcile Kissinger’s record in the region with anything the U.S. claims it stands for, as Washington continues to lecture other countries for their assumed lack or violation of democratic standards.

Darker and darker

Kissinger played a crucial role in another major war crime of the 20th century, East Timor’s large-scale massacres, ordered by Indonesian dictator General Suharto in December 1975.

In 1965, Suharto had overthrown nationalist leader Sukarno, ushering in one of the most murderous regimes in history, responsible for “one of the largest and swiftest, yet least examined, instances of mass killing and incarceration in the twentieth century—the shocking anti-leftist purge that gripped Indonesia in 1965-66, leaving some five hundred thousand people dead and more than a million others in detention.”13

A State Department telegram reported that, on December 6, 1975, Ford and Kissinger gave a clear “green light” to Suharto for his plan to invade East Timor, despite Suharto’s horrific record and his stated intention to take “rapid or drastic” action.

“It is important that whatever you do succeeds quickly,” Kissinger is on record as saying. In 2006, the final report from the East Timor Truth Commission stated that U.S. “political and military support were fundamental to the Indonesian invasion and occupation,” which cost an estimated 100,000 to 180,000 Timorese lives.14

Even more overlooked, and certainly more devastating in humanitarian terms, is Kissinger’s involvement with the East Pakistan atrocities of the spring of 1971, culminating in what the U.S. consulate in Dacca described as “genocide” of Bengalis, perpetrated by the Pakistani military led by General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan in the chain of events that led to the establishment of independent Bangladesh.

Nixon and Kissinger continued to protect, diplomatically support and even arm Yahya, in part because of the latter’s support for the China opening initiative, even if, in April 1971, the U.S. Consul in Dacca, Archer Blood, bravely voicing a dissenting note in the notorious “Blood telegram,”15 clearly informed the U.S. government that, “unfortunately the overworked term genocide” applied to the situation in East Pakistan.

Princeton scholar Gary J. Bass authoritatively recounts this story in his important and diligently researched book The Blood Telegram.16 Consul Blood’s “insubordination” prompted the irate reaction of Kissinger, who would call Blood “this maniac in Dhaka” and finally had him sacked.

Analyst Sajit Gandhi documented how Nixon and Kissinger ultimately operated the “tilt” in favor of General Yahya Khan, a personal friend of Nixon, in the South Asia crisis that opposed India to Pakistan in 1971.

Refusing to acknowledge the first free election results of December 1970, which would have concentrated political power in the East Pakistan region, General Yahya suspended the opening of the National Assembly indefinitely and, on March 25, 1971, proceeded with a systematic campaign of indiscriminate killing in East Pakistan, largely perpetrated with U.S. weapons, which resulted in an estimated casualty figure of as many as three million civilians.

Professor Bass makes clear that the events in East Pakistan “had a monumental impact on India, Pakistan and Bangladesh” and that, “in the dark annals of modern cruelty,” the slaughter in what is now Bangladesh “ranks as bloodier than Bosnia, and by some accounts in the same rough league as Rwanda.”

The understatement of Kissinger’s war crimes in the context of the American experience

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that, given the magnitude and gravity of his criminal policies, the dark side of Kissinger’s record has been understated, underreported when not outright ignored.

It is equally challenging to ignore the fact this attitude is consistent with an extensive pattern in U.S. legacy media and academia, which routinely understate the devastating civilian toll exacted by U.S. foreign policy, most particularly the massive abuse of the air force and its effects.

The reduced sensitivity to the exploitation of air bombing campaigns points to structural factors in the American historical experience.

The last conflict fought on U.S. soil happened to be the Civil War. With the isolated case of Pearl Harbor, which did not take place in the “mainland” and was overwhelmingly a military target, the U.S. has never been subjected to air bombing campaigns.

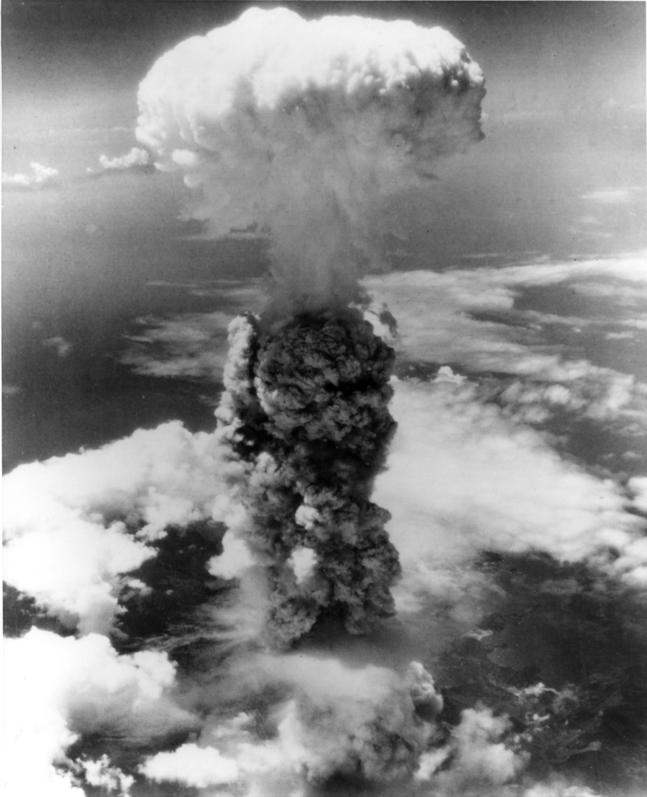

In what Carl Jung would describe as the “collective unconscious” of the U.S., exposure of a massive bombing is not, and perhaps cannot be, a powerful or evocative image. It is quite plain how this side of the U.S. experience stands in sharp contrast to the historical memories of many people in Europe, but even more so, of course, in countries such as Japan or, precisely, Cambodia or Vietnam.

Reviewing the record of a century of U.S. air force interventions, journalist Nick Turse noted that “indiscriminate airstrikes have been a U.S. hallmark from the ‘banana wars’ [of the 1920s] to the forever wars” of the 21st century. Over the last century, the U.S. government has not only advertised its wars as benign, but has also represented “its air campaigns as precise, its concern for civilians as overriding, and the deaths of innocent people as ‘tragic’ anomalies. Such campaigns have mainly served to obscure the true toll of the American way of war.”

The real impact and long-term cover-up of the Cambodia bombing is certainly a case in point.

The U.S. firebombing of Japanese cities during World War II, due to its particularly indiscriminate nature, is still an underreported and misunderstood case. Led by General Curtis LeMay, the U.S. air campaign culminated in the notorious firebombing of Tokyo on March 9-10, 1945. “In contrast to earlier U.S. tactical bombing strategies emphasizing military targets,” Mark Eden points out in The Asia-Pacific Journal, “their mission was to reduce much of the city to rubble, kill its citizens, force survivors to flee, and instill terror in the survivors.” LeMay himself candidly admitted that, “if we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals.”

As of now, the U.S. remains the only country in history to have ever used atomic weapons against civilians (or anyone else), while mainstream media and academia continue to defend the necessity of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear bombings to end the Pacific War, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.17

The massive bombing against Vietnam18, Cambodia and Laos, initiated by President Johnson and continued by Nixon and Kissinger, should therefore be regarded as part of consistent conduct in U.S. foreign policy.

So is the continuous understating or underreporting of its civilian casualties, as the Vietnam case illustrates compellingly. While the statistic of about 58,000 American military deaths in the conflict is quoted to exhaustion, the immensely higher Vietnamese losses barely figure in standard media coverage. As the World Peace Foundation notes, as of today, there is not even a satisfactory analysis of Vietnamese civilian casualties in the conflict, with the gravest estimates pointing to a total toll of more than 1,000,000 “war-related deaths.”

Kissinger’s legacy and the U.S. standing in the world

On March 17, 2023, in a virtually unique case for a major Western leader, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants against Russian President Vladimir Putin for the alleged “war crime of unlawful deportation of population and that of unlawful transfer of population from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation,” on grounds that are actually strongly controversial.

It is hard to ignore the fact that Kissinger was never called to answer for any of his immensely more serious crimes, which resulted in mind-blowing civilian casualty rates.

Stephen Miles, President of the activist network Win Without War noted that “Kissinger’s true impact was not just in being a war criminal but in setting a new standard for doing so with impunity.”

“Adding insult to all these injuries, Kissinger cashed in over the past 45 years through sustained influence peddling and self-promotion,” Tom Blanton ponders ominously, “paying no price for repeated bad judgments like opposing the Reagan-Gorbachev arms cuts, and supporting the 2003 Iraq invasion. A dark legacy indeed.”

What should we make, then, of Henry Kissinger’s legacy?

Several well known academics point out that the U.S. political establishment today could make effective use of Kissinger’s talent for détente, pragmatism and negotiating ability, particularly in the policies with Russia and China.

This author does not disagree in principle. In isolation, Kissinger did make sensible comments regarding the genesis of the Ukraine crisis, even acknowledging the U.S. role in provoking the current conflict, while offering sound policy advice which, as David Hendrickson notes, “could have avoided the conflagration in Ukraine.”19

Kissinger also indicted the irresponsible saber-rattling toward China, which could lead to catastrophic escalation in the region, with senior Chinese officials insisting that Kissinger’s “realist” approach would be beneficial to U.S.-China relations today.

Pundits also frequently pointed to Kissinger’s “towering intellect” and it is hard to deny that Kissinger’s outstanding knowledge of world history and diplomacy is not a common trait in the current U.S. party system, actually affected by a sharp dumbing down of the political culture.20

Yet, facing a statesman who repeatedly supported even genocidal policies, the same scholars and reporters would have been wiser in offering a more accurate coverage of Kissinger’s atrocious human rights and anti-democratic record, which is still, by contrast, largely unacknowledged in mainstream narratives.

Kissinger was all along a man of the American power establishment, which revered and eagerly sought his presence and advice until the very end.

In the spring of 2023, Kissinger was treated to two magniloquent receptions for his 100th birthday, at The Economic Club of New York and the New York Public Library, gathering an astonishing VIP list. Such pompous celebrations of Kissinger, Stephen Miles notes, are “attended not just by crusty old Cold Warriors remembering ‘the good ole days,’ but also by a veritable who’s who of today’s elite from billionaire CEOs and cabinet members to fashion megastars and NFL team owners.”21

This distorted representation of the controversial statesman is not going to be well regarded either in the Global South or all the countries so cruelly affected by Kissinger’s policies.

As the U.S. hegemony is increasingly eroded by an evolving, multipolar world, the biased and largely celebratory commemoration of Henry Kissinger does not speak well for the U.S. ability to come to terms with its role in the world.

Endnotes

- Niall Ferguson, Kissinger: 1923-1968: The Idealist, Penguin Press, 2015. Ferguson is reportedly working on volume II of this endeavor.

- As shown infra, in several important instances, such as the “China opening”, Kissinger received undeserved credit, for initiatives he did not actually promote. ↩︎

- It is quite significant that the Nobel Prize’s official website itself recalls that Le Duc Tho “refused to accept the Prize, and for the first time in the history of the Peace Prize two members left the Nobel Committee in protest” against the decision to award it to Kissinger. ↩︎

- John A. Farrell, Richard Nixon: The Life, Doubleday, 2017. Farrell was finally able to prove the plot through records released by the Nixon Presidential Library. However, while Nixon’s attempt to undermine Johnson’s peace talks with Vietnam is now proven, whether that had a real impact on the negotiation’s ultimate failure is still disputed. ↩︎

- Jeffrey P. Kimball and William Burr, Nixon’s Nuclear Specter, The Secret Alert of 1969, Madman Diplomacy, and the Vietnam War, University Press of Kansas, 2015. ↩︎

- Nixon and Kissinger apologists have hopelessly tried to defend the theory that the 1972 “Christmas Bombing” ultimately forced North Vietnam to negotiate the ceasefire of January 1973. As even the US State Department’s official history acknowledges, the 1973 ceasefire did not exact any more concessions from Hanoi than the previous proposals of October 1972, prior to the “Christmas bombing”, and it was chiefly Nixon’s and Kissinger’s enhanced pressure on reluctant South Vietnam president Thieu, among other factors, that ultimately brought about the 1973 agreement. That theory is also absurd at face value, considering that North Vietnam and its allies had been subject to intense bombing since 1964, which did not achieve any political result other than expanding the support for the Vietcong. ↩︎

- This figure, if computed per capita, could actually make Laos the most bombed country in history. ↩︎

- It is also worth noting that this was certainly only a brief parenthesis in Kissinger’s relationship with the US power establishment in general. As his subsequent records shows abundantly, Kissinger was profoundly connected to, and protected by the most conservative and warmongering factions of the US establishment until the end of his life. ↩︎

- There is a broad consensus on this point. In the exchange hosted by The Harvard Gazette, Professor Logevall also remarked that the China opening was “more Nixon’s doing than Kissinger’s, as Kissinger was initially a skeptic on the endeavor”. ↩︎

- The richly documented book by Peter Kornbluh, The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability, The New Press, 2013 [New Edition], remains a leading reference. ↩︎

- See John Dinges, The Condor Years: How Pinochet And His Allies Brought Terrorism To Three Continents, The New Press, 2005. The regimes in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay participated in the operation, which was set up in 1975. ↩︎

- The U.S.-led destabilization of Allende’s government started early on in the 1970s. During a meeting with Nixon and Kissinger on September 15, 1970, DCI Richard Helms noted down the directive to “make the [Chilean] economy scream.” ↩︎

- Geoffrey B. Robinson, The Killing Season: A History of the Indonesian Massacres, 1965-66, Princeton University Press, 2018. In the fundamental The Jakarta Method, Washington’s Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World, PublicAffairs, 2021, reporter Vincent Bevins showed that Suharto’s mass killing was taken as an “inspiring” paradigm for subsequent anti-communist terror campaigns around the world, notably in Brazil and Chile. ↩︎

- Other estimates have put the final toll at even 200,000 casualties. ↩︎

- Blood signed on the cable also in support of the dissenting view expressed against US policy by a group of foreign service officers. In Washington DC, State Department senior officials specializing in South Asia affairs endorsed the telegram in a letter to US State Department Secretary William Rogers. ↩︎

- Gary Bass, The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide, Knopf, 2013. ↩︎

- Professor Peter Kuznick, director of the Nuclear Studies Institute at American University, also authored, with Japanese historian Akira Kimura, the revisionist work Rethinking the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Japanese and American Perspectives, Kyoto: Horitsu Bunkasha, 2010, which, quite revealingly, is still largely unavailable in the US. ↩︎

- True to form, Curtis LeMay advocated an explicit threat against North Vietnam, to either “stop aggression” or the US would “bomb them back into the Stone Age”. ↩︎

- Although it should be noted that Kissinger partly backpedaled later on, especially about Ukraine’s membership to NATO. ↩︎

- New York Times author Andy Borowitz so argues in his unceremoniously titled book Profiles in Ignorance: How America’s Politicians Got Dumb and Dumber, Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster, 2023. ↩︎

- Miles, in his intervention for Responsible Statecraft, actually unwittingly references Kissinger’s 90th birthday party, which only reinforces the point. ↩︎

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Dario Calvisi is an independent researcher and analyst of U.S. foreign policy.

Dario is from Italy and currently based in Washington, DC.