But Now, More and More Young Jews Are Waking Up and Learning to Think for Themselves

If you talk to an ordinary American, or, in my experience, if you talk to an average Israeli, for that matter, they don’t know anything about who the Palestinians are. They don’t know where they come from, they don’t know how they live, what they believe, and they don’t want to. Right? Because that just complicates things… – historian Sam Biagetti.

Last month, The New York Times conducted a series of interviews with a number of American Jewish families and the way they have been dealing with what the paper calls a “generational divide over Israel.”

The Times notes a trend that has been developing for a long time—younger American Jews becoming markedly more critical of, sometimes downright hostile to, Israel than their elders. The piece looks at “more than a dozen young people…[who] described feeling estranged from the version of Jewish identity they were raised with, which was often anchored in pro-Israel education.”

One such person is Louisa Kornblatt. She is the daughter of liberal Jewish parents, who grew up experiencing the cruelties of anti-Semitism in suburban New Jersey. Her grandmother “had fled Austria in 1938, just as the Nazis were taking over.” Partly as a result of this legacy, Louisa Kornblatt “shared her parents’ belief that the safety of Jewish people depended on a Jewish state” as a child.

However, her views began to shift once “she started attending a graduate program in social work at U.C. Berkeley in 2017.” As she recalls it, “classmates and friends challenged her thinking,” with some telling her that she was “on the wrong side of history.”

While in graduate school, “she read Audre Lorde, Mariame Kaba, Ruth Wilson Gilmore and other Black feminist thinkers,” who further made her re-think ingrained assumptions. Eventually, “Kornblatt came to feel that her emotional ties to Jewish statehood undermined her vision for ‘collective liberation.’”

“Over the last year, she became increasingly involved in pro-Palestine activism, including through Jewish Voice for Peace, an anti-Zionist activist group, and the If Not Now movement.” She now goes so far as to assert, “I don’t think the state of Israel should ever have been established,” because “It’s based on this idea of Jewish supremacy. And I’m not on board with that.”

Also interviewed are the parents of Jackson Schwartz, a senior at Columbia University whose education there has significantly altered his outlook on Israel:

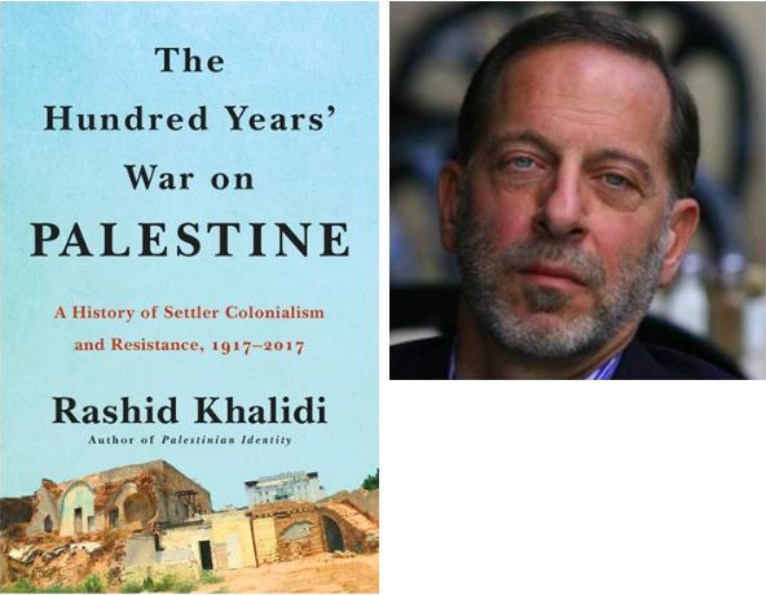

“The parents of Mr. Schwartz…said they listen to him with open minds when he tells them about documentaries he has seen or things he has learned from professors like Rashid Khalidi, a prominent Palestinian intellectual who is a professor of modern Arab studies at Columbia. Dan Schwartz said his son helped him understand the Palestinian perspective on Israel’s founding, which was accompanied by a huge displacement of population that Palestinians call the Nakba, using the Arabic word for catastrophe.”

“It wasn’t until Jackson went to Columbia and took classes that I ever heard the word Nakba,” Dan Schwartz said.

These interviews are hugely instructive for two reasons. For one thing, they demonstrate very clearly why power centers are so critical of higher education, especially in the humanities: They are afraid young people might actually—horror of horrors—learn something, particularly something that challenges the status quo.

American culture overflows with accusations from parents that their kids went off to college only to be “indoctrinated.” But at least in these instances, the opposite is what happened—far from being brainwashed, the kids read books and learned history, and were forced to think hard about the implications. In other words, higher education did exactly what it is supposed to do—forced students to encounter and engage with perspectives and thinkers they otherwise never would have.

In reality, most parents (and certainly media outlets) who complain of indoctrination are actually worried about education—that is, that their children will develop more nuanced, critical and informed views of the world after engaging with unfamiliar viewpoints. Such aggrieved elders don’t see it this way, of course, largely because they themselves never shook off the propaganda of their youth. Indeed, they likely are not even capable of perceiving it as such. But that is what it is.

The interviews from the Times piece also demonstrate what Sam Biagetti refers to in the quote that sits atop this article: the phenomenon of older Americans who profess attachment to (and presumably knowledge of) Israel, displaying aggressive—no, fanatic—ignorance about basic Israeli/Middle East history.

That Mr. Schwartz had never heard of the Nakba until his son learned about it from Rashid Khalidi speaks volumes about the way young people in this country are “taught” about Israel, as well as how much their parents actually “know” about it. It is the equivalent of a German father professing fierce attachment to the German nation-state, but never hearing the word “Holocaust” until his child tells him about it after learning the history from a Jewish professor.

The new documentary Israelism explores this issue of younger Jewish people raised to reflexively identify with Israel and to view it as a “Jewish Disneyland,” but who changed their minds (and behavior) upon encountering the brutal realities of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.

It is a powerful film, one that takes a look at the too-often ignored indoctrination regarding Israel taking place in many Jewish day schools, the way younger people are starting to de-program themselves from it, and where they go from there.

Directed by first-time filmmakers Erin Axelman and Sam Eilertsen, Israelism largely follows two protagonists whose experiences mirror those of the filmmakers.

The first protagonist, Eitan (whose last name is never revealed), grew up in a conservative Jewish home in Atlanta. Typical of such an upbringing, he was steeped in pro-Israel PR.

He recounts that “Israel was a central part of everything we did in school.” His high school routinely sent delegations to AIPAC (the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, also known as the “Israel lobby”) conferences.

Outside of school, the PR continued. He describes going to Jewish summer camp, where each year the staff included a group of Israeli counselors, brought in “to connect American Jews to Israeli culture.”

This included having the children playing games designed to simulate being in the Israeli military, including the use of actual Israeli military commands.

The film intersperses interviews of its protagonists with interviews of prominent individuals who promote this Israeli PR.

For instance, Rabbi Bennett Miller, the then-National Chair of the Association of Reform Zionists of America, asks with a laugh, “does [my] average congregant understand that I’m teaching them to become Zionists? Probably not, but it is part of my madness, so to speak.”

Enamored with what he saw as the glory of military service, Eitan told his parents that he was going to join the Israeli military rather than go to college. He had always thought of Israel as “my country,” and learned from numerous childhood visits there that he “fit in” better in Israel than in the United States.

During basic training with the IDF, he was trained as a “heavy machine gunnist” [sic] with an emphasis on urban warfare. After seven months of this, he was deployed to the West Bank. His life in the IDF involved operating the various checkpoints which comprise the apartheid system, as well as patrolling Palestinian villages on foot in full gear with a bulletproof vests. He recounts that on such patrols, the mission of his unit was to make their presence felt, in order “to let them know that we were watching.”

His encounter with the occupation changed him forever. “Even though Israel was a central part of everything we did in school,” he recalls, “we never really discussed the Palestinians. It was presented to us that Israel was basically an empty wasteland when the Jews arrived. ‘There were some Arabs there,’ they said, but there was no organized people; they had really treated the land poorly. Yeah, there are Palestinians, [but] they just want to kill us all…” Furthermore, “It was always presented to us that the Arabs only know terrorism.”

His role as an occupier made him see things rather differently. He witnessed IDF soldiers needlessly abusing captives, who were blindfolded and handcuffed, thrown to the ground, kicked and beaten. He despairs that he “didn’t even speak up,” something he is visibly still struggling with. And, he says, “that’s just one of many stories that I have from my time in the West Bank. It took many years to really come to terms with my part in it. Only after I got out of the army did I begin to realize that the stuff that I did [from] day to day, just working in checkpoints, patrolling villages—that in itself was immoral.”

After great difficulty, Eitan has begun to publicly speak out about his experiences, though he notes that it took a long time, and that on his first attempt, he was not able to make it through without crying excessively. Since then, he has gotten better, and continues to pursue this necessary work.

Israelism’s second protagonist is Simone Zimmerman. Zimmerman’s grandfather settled in Israel; he and his immediate family were some of her only relatives to escape the Holocaust. Zimmerman herself was raised in a staunchly pro-Israel household, attending Hebrew school from kindergarten through high school. While in high school she lived in Israel for a period as part of an exchange program, which was just one of many visits.

These organized stays in Israel routinely involved her and her friends dressing up in Israeli army uniforms and pretending to be in the IDF. She participated in Jewish youth groups and summer camps which, like Eitan, immersed her in a steady diet of pro-Israel propaganda. Summing up her childhood experience, Zimmerman explains that “Israel was just treated like a core part of being a Jew. So, you did prayers, and you did Israel.”

Like Eitan, she was familiar with AIPAC: “AIPAC is just the thing that you do. Like, going to the AIPAC conference is just sort of seen as a community event.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, almost ten percent of her high school graduating class ended up joining the Israeli army, and many of her summer camp and youth group friends did as well. This is the power of effective propaganda instilled from a young age, Zimmerman observes. “The indoctrination is so severe, it’s almost hard to have a conversation about it. It’s heartbreaking.”

Israelism contains footage of this indoctrination in action inside Hebrew schools.

Scenes of teachers excitedly asking classes of young children, “do you want to go to Israel too?” and the children screaming back, “YEAH!!!” are reminiscent of the similarly nauseating kinds of religious indoctrination made famous in an earlier era by films like Jesus Camp.

Some of these scenes can be glimpsed in the trailer for the film. Older students are seen reading copies of Alan Dershowitz’s book The Case for Israel, which was famously exposed as a fraud by Norman Finkelstein years ago. Zimmerman herself gets to look at some of her old worksheets and art projects from her elementary school days, all of which in some way revolved around the Israeli state.

Other than enlisting in the IDF, Zimmerman had been told that the other major way to be “a good supporter of the Jewish people” was to become an “Israel advocate.” Choosing the latter path, Zimmerman became involved with Hillel, the largest Jewish campus organization in the world, when she began attending the University of California at Berkeley. Hillel, too, worked very hard to instill pro-Israel beliefs in her. She describes being trained in how to rebut “the ‘lies’ that other people [were] saying” about Israel.

The film explores the nature of Hillel’s work fostering pro-Israel activism at college campuses across the country. Tom Barkan, a former IDF soldier and “Israel fellow” at the University of Connecticut’s Hillel chapter, says, “name a university in America, we probably have a person there.” Barkan’s mission is to turn Jewish college students into either Israel advocates or military recruits. While he warns eager students that joining the IDF will not be easy, he wistfully tells them that it will be “the most meaningful experience that you ever go through.”

Former Jewish day school teacher Jacqui Schulefand works with Barkan in her role as Director of Engagement and Programs at UConn’s Hillel branch. Her love for the State of Israel is inseparable from her identity as a Jewish person, which she proudly explains. “Can you separate Israel and Judaism? I don’t know—I can’t. You know, some people I think can. To me, it’s the same. Yeah, you can’t separate it. Israel is Judaism and Judaism is Israel. And that is who I am, and that is my identity. And I think every single thing that I experienced along my life has melded into that, like there was never, you know, a divide for me.”

Schulefand describes joining the Israeli armed forces as “the greatest gift you can give,” and notes that “we actually have had quite a few of our former students join the IDF—amazing!” But her demeanor sours when she is asked about criticisms of the country. In a tone combining incomprehension with a hint of disgust, she laments that “somehow, ‘pro-Palestinian’ has become ‘pro-social justice.’”

It was this sort of pro-Israel advocacy network that organized Simone Zimmerman and other students to oppose what they perceived to be “anti-Semitic” activities such as student government legislation favoring the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israeli occupation, and other measures critical of Israel.

To prepare for such confrontations, she was handed talking points that told her what to say—accuse critics of being anti-Semitic, of having a double standard, of making Jewish students feel unsafe, etc. Describing her feelings about BDS and the Palestinian cause at the time, Zimmerman says that “I just knew that it was this bad thing that I had to fight.” She remembers literally reading off the cards when it came time for her to make the case for Israel.

However, such work inevitably brought her into contact with people who challenged her views. She encountered terms like apartheid, ethnic cleansing, and illegal occupation. “I thought I knew so much about Israel, but I didn’t really know what anybody was talking about when they were talking about all these things,” she said.

Growing up, she was barely taught anything about Palestinians, much like Eitan: “The idea that there were native inhabitants who lived there [when settlers began to arrive] was not even part of my frame of reference.”[1] To the extent that her upbringing provided her with any conception of what a Palestinian was, it was that a Palestinian was someone “who kills Jews, or wants to kill Jews.” But now she was dealing with actual Palestinian students and their non-Palestinian allies, who told her things she found alarming.

Zimmerman went back to Hillel, embarrassed that she and the other pro-Israel advocates were not doing a good job refuting the information they had been confronted with. When Zimmerman asked what the proper responses were to specific criticisms directed at Israel—other than shouting “double standard” or “anti-Semitic”—no one provided her with any. “That was really disturbing for me,” she says. She was flabbergasted that “there are these people called Palestinians who think that Israel wields all this power over their lives and don’t have rights, don’t have water. What is this? How do I respond to it?” “How is it that I am the best the Jewish community has to offer—I’ve been to all the trainings, all the summer camps—and I don’t know what the settlements are, or what the occupation is?”

This anguish led Zimmerman to see the occupation for herself, the summer after her freshman year. This was her first time “crossing the line” into the West Bank. The film movingly details her experiences there. She listened to Palestinian families describe routine instances of being beaten by the IDF, and the harsh realities of life under military rule.

She befriends Sami Awad, Executive Director of the Holy Land Trust, who works to give Americans tours of the territory. An American citizen born in the U.S., Awad describes encounters with American kids who have joined the IDF, people “who just moved here to be part of an army to play cowboys and Indians.” He remarks on the absurdity that “Somebody…comes here from New York or from Chicago, and [claims] that this land is theirs.”

Awad’s family was originally from Jerusalem. His grandfather was shot by an Israeli sniper in 1948, and the rest of his family were evicted by Israeli forces soon after during the Nakba. They have never been allowed to return, and have lived under occupation ever since. Nevertheless, Awad is an extraordinarily empathetic person, having made a career out of trying to teach Westerners what life is like in the West Bank, in the hopes that they will use what they learn to effect positive change. He recounts visiting Auschwitz, and says that the experience gave him an insight into “inherited trauma” and how it shapes the conflict today. In the film he comes across as optimistic:

“I really believe that there is an emerging awakening within the American Jewish community…From American Jews, coming here, and listening to us, and hearing us, and seeing our humanity, and understanding that we are not just out sitting in bunkers, planning the next attack against Israelis, that we do have a desire to live in peace, and to have our freedom, and to walk in our streets, and to eat in our restaurants, and like we – I mean it’s crazy that I have to say this, that we are real human beings that just want to survive and live, like all other people in this world.”

Zimmerman also meets Baha Hilo, an English speaker who works as a tour guide with To Be There, another group that helps people understand the reality that Israel imposes on the West Bank. His family was expelled from Jaffa in 1948 during the Nakba. They were forced to settle in Bethlehem, sadly believing that they would eventually be able to return to their homes.

Hilo discusses his frustration that Israelis get to live under civil law, whereas Palestinians like him must live under the humiliating military law of the occupation: “When an American goes to the West Bank, he has more rights there than I have had my entire life!” The film takes care to note that Americans play a major role in such realities: “Of the roughly 450,000 [illegal] Israeli settlers living in the occupied West Bank, 60,000 are American Jews.” Some readers may recall the famous viral video of an Israeli named Yakub unashamedly stealing Palestinian homes while conveying a breathtaking sense of entitlement.

Hilo laments that, “From the day you are born, you live day in and day out without experiencing a day of freedom.” His astonishment at the audacity of Israelis, particularly those who are also Americans, mirrors Awad’s: “What makes an 18-year-old American kid who was given [a] ten days’ trip for free in Palestine, what makes him want to come in and sacrifice his life? Why would a foreigner think it’s ok to have superior rights to the rights of the indigenous population? Because somebody told them it’s [their] home.”

While happy to make such friends, Zimmerman nonetheless says of her time there, “I don’t think I realized the extent to which what I would come to see on the ground would really shock me and horrify me.” This experience often changes people. The filmmaker Rebecca Pierce is interviewed on her own visits to the West Bank, and her reaction is in line with Zimmerman’s. Pierce had always been opposed to using the word “apartheid,” but once she saw the reality of the situation, she changed her mind immediately.

The protagonist of With God on Our Side (a 2010 documentary critical of Christian Zionism), a young man named Christopher, had a similar reaction, specifically at the behavior he witnessed from the Israeli settlers. Each year a group of them converges on the Arab section of Old Jerusalem to celebrate Israel’s capture of East Jerusalem in 1967. Christopher witnessed the festivities, which featured a massive crowd of settlers wrapped in Israeli flags, shouting “death to Arabs” repeatedly as they danced through the streets.

A large group identified an Arab journalist, surrounded him, began chanting at him and flipping him off, to the point where the police had to be called. Christopher was visibly shocked at all this, glumly remarking that he “felt ashamed to be there.” This same celebration is also seen in Israelism, and the Israeli chants are as deranged as ever: “An Arab is a son of a bitch! A Jew is a precious soul!” “Death to the leftists!”

Zimmerman’s experiences led her to become a co-founder of the If Not Now movement, a grassroots Jewish organization which works to end U.S. support for Israel. They have engaged in activism targeting the ADL (more on them in a moment), AIPAC, the headquarters of Birthright Israel, and other organizations which directly contribute to the perpetuation of Israel’s occupation. “We decided to bring the crisis of American Jewish support for Israel to the doorsteps of Jewish institutions to force that conversation in public,” Zimmerman says.

Israelism contains powerful scenes of younger Jewish people engaging in this work. Many come from similar backgrounds as Eitan and Simone. Consider Avner Gvaryahu. Born and raised in Israel, Gvaryahu also joined the IDF. His combat experience ultimately turned him against the occupation. His whole life in Israel, he had never been inside a Palestinian home, but was now being tasked with “barg[ing] into one in the middle of the night.”

By the end of his service, he had routinely taken over Palestinian homes and used them as military facilities. No warrants were needed, and no notice was ever given to the families who were living there. He reflects back “with shame” on how violently he often acted toward the residents in such situations. Gvaryahu is now the Executive Director of Breaking the Silence, an organization of IDF veterans committed to peace.

“There are a lot of Jewish young people who see a Jewish establishment that is racist, that is nationalistic,” Zimmerman explains. Jeremy Ben-Ami, the President of J Street, agrees. “They’re really, really angry about the way they were educated, and the way they were indoctrinated about these issues, and justifiably so.”

While such courageous individuals often receive quite a bit of hatred from their own community (Zimmerman says, “The word I used to hear a lot was ‘self-hating Jew.’ Like, the only way a Jewish person could possibly care about the humanity of Palestinians is if you hate yourself”), their numbers are growing, and one hopes that this will continue. Israelism was released a few months before the terrorist attacks of October 7th and Israel’s genocidal response, events which make the film timely and important.

Since October 7th, we have seen many of the tactics and talking points used to justify Israel’s crimes that the film depicts return with a vengeance. Chief among them is the by-now ubiquitous claim that calling out Israeli atrocities is somehow anti-Semitic.

Zimmerman is anguished that “so many of the purported leaders of our community have been trying to equate the idea of Palestinian rights itself with anti-Semitism.”

This applies to no one more than Abraham “Abe” Foxman, who until his recent retirement was the long-time head of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), an organization masquerading as a civil rights group but which is really a pro-Israeli government outfit which has long sought to redefine anti-Semitism to include “criticisms of Israel.”

These efforts have borne fruit—“The Trump administration issued an executive order adopting” this definition of anti-Semitism “for the purposes of enforcing federal civil rights law,” Michelle Goldberg notes in The New York Times. Foxman says in the film that “it hurts me for a Jewish kid to stand up there and say ‘justice for the Palestinians,’ and not [say] ‘justice for Israelis’; it troubles me, hurts me, bothers me. It means we failed. We failed in educating, in explaining, et cetera.” Many Israel supporters seem to share Foxman’s horror that Jewish people sometimes care about the well-being of people other than themselves.

Israelism explores this deliberate conflation of anti-Semitism with anti-Zionism. Sarah Anne Minkin, of the Foundation for Middle East Peace, is deeply bothered that “The way we talk about anti-Semitism isn’t about protecting Jews, it’s about protecting Israel. How dangerous is that, at this moment with the rise of anti-Semitism?”

Indeed, the film contains footage of the infamous Unite the Right rally featuring hordes of white supremacists marching through Charlottesville, Virginia, with torches, screaming “Jews. Will not. Replace us!” over and over, as well as news footage of the aftermath of the Tree of Life Synagogue mass shooting.

One of the chief tasks of Israeli propagandists has been to conflate such acts with anti-Zionist sentiment. Genuine anti-Semitism of the Charlottesville variety is (obviously) a product of the far right—recall that President Donald Trump famously referred to “very fine people on both sides” of that incident, an unmistakable wink and nod to such fascist groups.

People who comprise such groups, the type who paint swastikas on Jewish homes, are not the same as peace activists marching to end the Israeli occupation. This should not be difficult to understand. But the Israel PR machine has done a marvelous job confusing otherwise intelligent people on this issue.

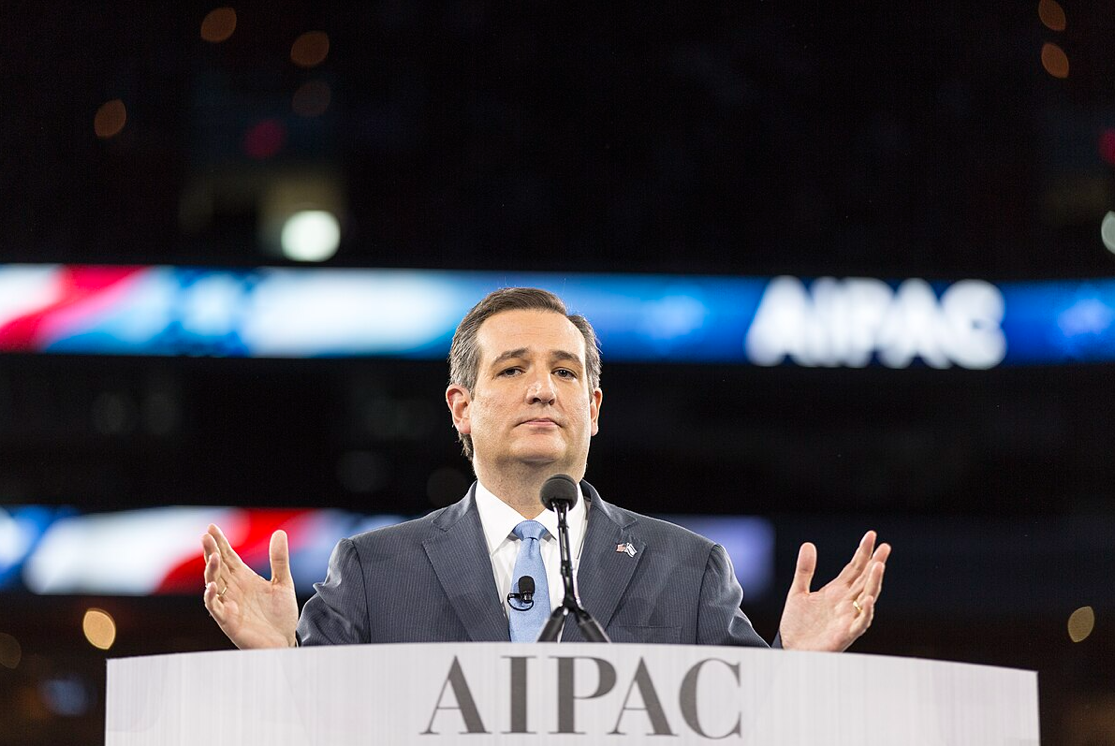

Also quoted in the film is Ted Cruz, who like Trump is a regular speaker at AIPAC events, and who like many Republicans pitches his political rhetoric to appeal to the very reactionaries who espouse genuinely anti-Semitic sentiments. This does not stop him from having the audacity to refer to criticisms of Israel as anti-Semitic, shamelessly insisting that “the left has a long history of anti-Semitism.”

The American right wing has been hard at work lately, trying to convince gullible people that the rise of actual anti-Semitic incidents is the result of critics of Israel. The New York Times’s Michelle Goldberg reports that “Chris Rufo, the right-wing activist who whipped up nationwide campaigns against critical race theory and diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, told me he’s part of a group at the conservative Manhattan Institute workshopping new policy proposals targeting what it sees as campus antisemitism.”

Such efforts apparently convince many liberal-leaning people to agree with UConn Hillel’s Jacqui Schulefand, who as noted above believes that “Israel is Judaism and Judaism is Israel.”

If you believe this, it is understandable how you might come to see criticizing a government’s policies, or the political ideology (Zionism) undergirding them, as anti-Semitic. I do not often profess gratitude for President Biden (indeed, I am really hoping the “Genocide Joe” label sticks), but it was nice to see him publicly state that “You don’t have to be a Jew to be a Zionist. And I’m a Zionist.” This pronouncement clarifies something that the Israel Lobby likes to obscure—that Zionism is a political ideology, like “conservatism,” “socialism” or “libertarianism.”

As such, critiquing it is not racist or anti-Semitic, even if the criticism is inaccurate.

It is always important to consider the ways in which assumptions held uncritically can lead one astray, especially assumptions ingrained from a young age, before people possess the capacity to sufficiently question what they are being told. Israelism is a powerful, thought-provoking film that does this spectacularly. And it does so for a topic that does not get as much attention as it should. Discussions of Christian propaganda are fairly common (again, think of Jesus Camp, or even With God on Our Side), as are denunciations of the kind of Islamic fundamentalist propaganda that comes out of places like Saudi Arabia.

It is almost too easy to go after the Mormons or the Scientologists. But the indoctrination taking place in many Jewish schools gets comparatively little attention. I have written previously of my admiration for people, like Naomi Klein, who frankly discuss the troubling fact that Israeli PR defined much of their early schooling. It is important to have an entire film devoted to the subject. People might not like what they see, but they need to see it.

Israelism is streaming here until January 31st.

-

Reflecting a broader trend, actor Seth Rogen complained on comedian Marc Maron’s podcast that he was “fed a bunch of lies” about Israel in his youth. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Kenny Cordasco is a graduate student at Rutgers University.

A professional merchant mariner and naval officer, he writes regularly at Cut the Cord on Substack.

Kenny can be reached at kcordasco@gmail.com.

1) Just how badly is our language and narratives corrupted when Whites opposing genocide is called “supremacist”? What? What’s with this normie outrage about Unite the Right? What is it they said that is “wrong”? I wager “nothing.” It is just you have been brainwashed in to hating White people.

2) Used to listen to NPR on the way to work. One woman told this tale of what must have been a day camp like mentioned here. There was a staged event where someone in a KKK costume bursts in to the room and supposed to scare everyone. There was absolutely no examination of *this* tactic all. She only told the story so she could brag (fantasize?) that when the other kids ran she punched the guy. Imagine this being done by others – like having some Black guy appear to scare children.

People also need to be educated about the Jewish Nakba which is often brushed under the carpet.

https://www.thetower.org/article/there-was-a-jewish-nakba-and-it-was-even-bigger-than-the-palestinian-one/

Here is some information that more people should be aware of:

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/protocols-of-the-elders-of-zion

I attended Hebrew School as a child and I was never indoctrinated to hate Palestinians. Actually the teacher never mentioned anything about Palestinians. I learned to read and write Hebrew, about stories in the Old Testament, about all the Jewish Holidays, but very little about current events, as the emphasis was more on biblical events and Jewish values and customs and the importance of performing mitzvahs (good deeds). To be honest often I was very bored and did not pay attention in class sometimes. I was not the best student in the class.

I think it is good for people to read different perspectives and not just read one sided reports that do not look at both sides of a story. So I am sharing another perspective:

https://jewishjournal.com/commentary/columnist/editors-note/359405/the-film-israelism-assaults-the-truth-and-hurts-palestinians/