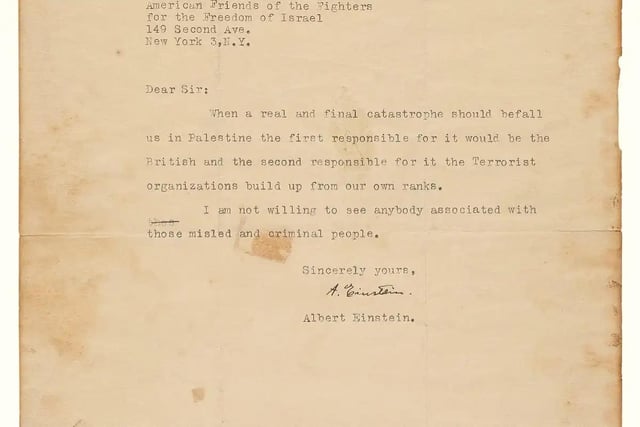

A few weeks before the creation of the State of Israel, Shepard Rifkin, executive director of the Stern Group, requested that representatives of the group meet with Albert Einstein in the United States, “the greatest Jewish figure of the time” according to I.F. Stone. Einstein’s response was unequivocal:

“When a real and final catastrophe should befall us in Palestine the first responsible for it would be the British and the second responsible for it the Terrorist organizations built up from our own ranks. I am not willing to see anybody associated with those misled and criminal people.”[1]

To grasp Einstein’s prescience, one need only replace “the British” with “the Americans” and “terrorist organizations” such as the Stern Group and the Irgun group with the Netanyahu government, the political descendants of the leaders of these groups, Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir.

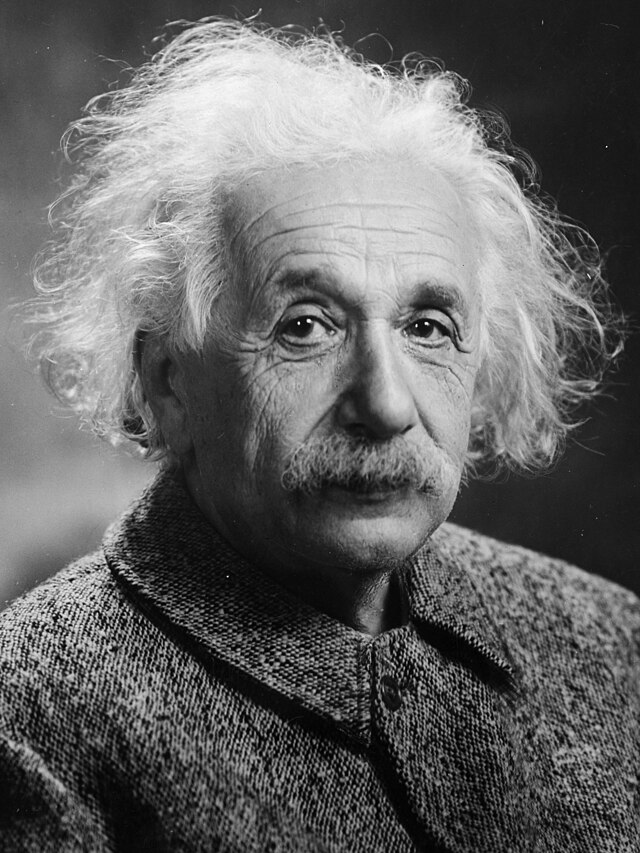

Einstein said that his “life was divided between equations and politics.” Yet, among his biographers—there are hundreds of them—and in the mainstream media, his extensive political writings on Israel and Zionism have been, at best, swept under the rug. At worst, completely distorted making him a supporter of the State of Israel.

That is until the late Fred Jerome sought them out, found them, had them translated, mostly from German, and published them in the book Einstein on Israel and Zionism.

Unfortunately, the first edition of this book, published by a New York publishing house, had a very small print run, was never promoted or made into an e-book, and sold out in no time, the publisher having bowed to enormous pressure from the Zionists. That is why Baraka Books has published a new edition with the agreement of Jocelyn Jerome, the author’s widow.

It was in Germany in the 1920s, a time of rampant anti-Semitism when the theory of relativity was attacked as “Jewish science,” that Einstein was drawn to the Zionist movement. It was not until 1914, when he arrived in Germany, that he “discovered for the first time that he was a Jew,” a discovery he attributed more to “Gentiles than Jews.” Before that, he had seen himself as a member of the human species.

He called himself a “cultural Zionist,” but as early as 1921 Kurt Blumenfeld, a Zionist activist sent to recruit Einstein, warned Chaim Weizmann, the future president of Israel, about the great scientist:

“Einstein, as you know, is no Zionist, and I ask you not to try to make him a Zionist or to try to attach him to our organization…Einstein, who leans to socialism, feels very involved with the cause of Jewish labor and Jewish workers…I heard…that you expect Einstein to give speeches. Please be quite careful with that. Einstein…often says things out of naïveté which are unwelcome by us.”

Apart from Einstein’s supposed “naivety,” Blumenfeld could not have said it better. Einstein would be a constant obstacle to the Zionist project of colonization of Palestine and the creation of the State of Israel until his death in 1955.

Here are some examples of the positions he took.

His exchanges with Chaim Weizmann, the future president of Israel, illustrate how important Einstein was to the Zionists, but more importantly how his views differed from theirs. In a letter to Weizmann on November 25, 1929, he wrote:

“If we are not able to find a way to honest cooperation and honest pacts with the Arabs, then we have learned nothing during our two thousand years of suffering, and deserve the fate which will befall us.”

The idea of “the fate which will befall us” recurs often. In 1929, he seems to have already foreseen that the State of Israel the Zionists dreamed of creating without “honest cooperation and honest pacts” with their Palestinian neighbors would become what it is today, namely the most dangerous place in the world for Jews to live.

A few weeks later, on December 14, 1929, he wrote to Selig Brodetsky of the Zionist Organization in London, “I’m happy that we have no power. If national pigheadedness proves strong enough, then we will knock our brains out as we deserve.”

Furthermore, Leon Simon, one of his early editors and translators, wrote:

“There is in Professor Einstein’s nationalism no room for any kind of aggressiveness or chauvinism. For him the domination of Jew over Arab in Palestine, or the perpetuation or a state of mutual hostility between the two peoples, would mean the failure of Zionism.”

Unlike the vast majority of Zionists, Einstein’s support for a possible “Jewish homeland”—not a state—was not limited to Palestine. There was nothing religious in his commitment. Some Zionists advocated the establishment of such a homeland in China, Peru or Birobidjan in the Soviet Union, but in full agreement with the state authorities and the populations in each case.

Einstein supported these steps. For example, on the Jewish homeland of Birobidjan in the Soviet Union after the Second World War he wrote:

“We must not forget that in those years of atrocious persecution of the Jewish people, Soviet Russia has been the only great nation who has saved hundreds of thousands of Jewish lives. The enterprise to settle 30,000 Jewish war orphans in Birobidjan and secure for them in this way a satisfying and happy future is new proof for the humane attitude of Russia towards our Jewish people. In helping this cause we will contribute in a very effective way to the salvation of the remnants of European Jewry.”

In the pivotal years between the end of the war and his death in 1955, Einstein was outspoken about the Jewish state project. Invited to testify before the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on Palestine in Washington, D.C., in January 1946, Einstein answered unequivocally when asked about the possible State of Israel versus a cultural homeland: “I have never been in favor of a state.”

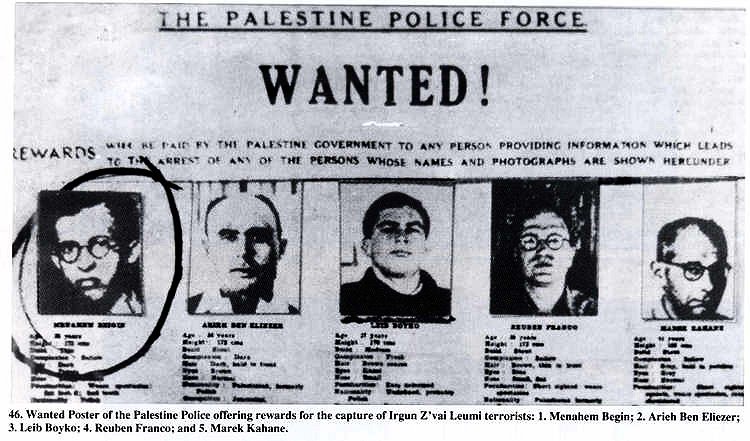

In March 1947, I.Z. David, a member of the Irgun terrorist group led by Menachem Begin, sent him a questionnaire to which he responded sharply and clearly:

Question: What is your opinion about the establishment of a free National Jewish Palestine?

Einstein: Jewish National Home? Yes. Jewish National Palestine? No. I favor a free, bi-national Palestine at a later date after agreement with the Arabs.

Question: Opinion about partition of Palestine and Chaim Weizmann’s proposals re partition?

Einstein: I am against partition.

On the question of British and American imperialism, Einstein had no illusions as London handed over to Washington:

“It seems to me that our beloved Americans are now patterning their foreign policy on the model of the Germans, since they appear to have inherited the latter’s inflatedness and arrogance. Apparently, they also want to take on the role England has played up to now. They refuse to learn from each other; and learn little even from their own harsh experience. What has been implanted into the heads from early youth is rooted more firmly than experience and reasoning. The English are yet another good example of this. Their old-fashioned methods of suppressing the masses by using indigenous unscrupulous elements from the economic upper class will soon cost them their whole empire, but they are incapable to bring themselves to change their methods; no matter whether it’s the Tories or the Socialists. With the Germans, it was exactly the same. All of this would be good and well, except for the fact that it’s so sad for the better elements and the oppressed… (Letter to Hans Mühsam)

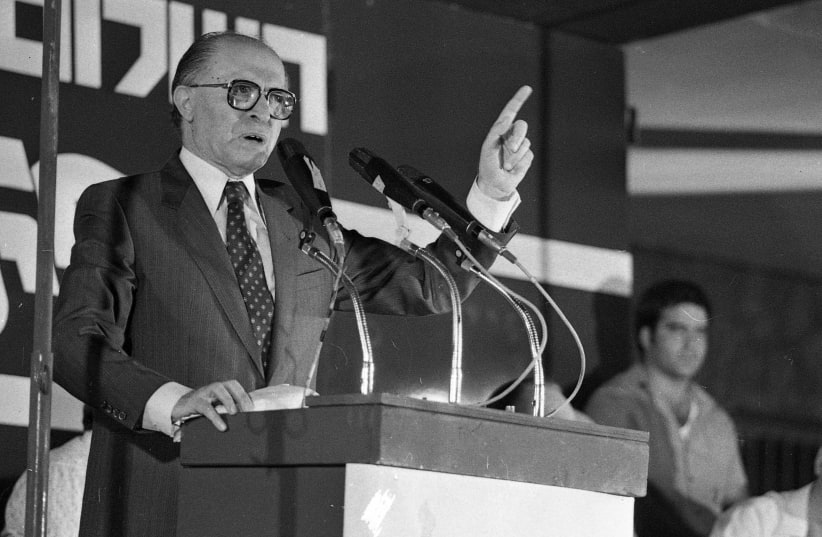

As for the political ancestors of the current Netanyahu government, Einstein tore into them and their political parties, particularly in The New York Times. When Menachem Begin came to New York in late 1948, Einstein, Hannah Arendt, and other Jewish figures in the United States published a letter denouncing his visit and the organization he led calling it “a political party very close in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and fascist parties.” One example they cited was the massacre of 240 men, women, and children in the Palestinian village of Deir Yassin.

Einstein would repeat this accusation until his death in 1955: “These people are Nazis in their thoughts and actions.” Anyone who says this today in the mainstream media is immediately labeled an anti-Semite and banned from the same media.

It is common knowledge that when Chaim Weizmann died in 1952 the Prime Minister of Israel offered the presidency of Israel to Albert Einstein. Less well known, however, is the reason Einstein gave for this refusal: “I would have to say to the Israeli people things they would not like to hear.” Even less well known is Ben Gurion’s statement: “Tell me what to do if he says yes! I’ve had to offer him the post because it was impossible not to, but if he accepts we are in for trouble.”

Hundreds, if not thousands, of people are being accused of anti-Semitism or fired from their jobs because they dare to criticize the State of Israel, call it an apartheid state, and denounce the genocide of the Palestinians. May they rest assured: they are in good company, because if Einstein were alive today, he would be in the front lines demonstrating with them.

All quotes are from Einstein on Israel and Zionism, New Enriched Edition by Fred Jerome. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Robin Philpot is a graduate of the university of Toronto and founder of Baraka Books in Montreal.

He is author of A People’s History of Quebec, with Jacques Lacoursière (Baraka Books, 2009); and Rwanda and the New Scramble For Africa: From Tragedy to Useful Imperial Fiction (Baraka Books, 2013), among other works.

Robin can be reached at philpotrobin@gmail.com.

Here is a video of Albert Einstein speaking in the year 1951 in which he refers to “the establishment of the independent state of Israel” This shows that in the year 1951 he had accepted the creation of the State of Israel even though prior to 1948 he had expressed some reservations about this.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZXDb3gExaQw

Here is an article about Einstein’s last speech before he died in 1955. This speech gives one a better idea of Einstein’s feelings about Israel and the conflict in the Middle East:

https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/einsteins-last-speech

Although Einstein had differences of opinion with other Jewish people he always had a very strong bond with the Jewish people as described in the Forward Magazine:

Einstein felt a deep bond with the Jewish people, one that transcended religion as well as the anti-Semitism that Nazis and their sympathizers leveled against him..

Despite his differences with fellow Jews in their practices and beliefs, Gimbel says, Einstein recognized that the relationship he had with Jewish friends was fundamentally different from the one he had with non-Jewish friends. He came to believe that whatever their beliefs, Jews shared common traits.

The first trait Einstein identified as common among Jews was an ability to face the world with a sense of awe and joy, whether the Jews in question were rapturous Hasidim or secular physicists.

The second trait Einstein identified was a sense of social justice. As he wrote in 1938, “The bond that has united the Jews for thousands of years and that unites them today is, above all, the democratic ideal of social justice coupled with the ideal of mutual aid and tolerance among all men.”

When Weizmann, Israel’s first president, died in 1952, Einstein, still a pacifist and an internationalist, was not an obvious choice. He had been a refugee from Germany since 1933, and had spent the past 20 years living in Princeton, New Jersey, where he was now a U.S. citizen. But he was still the most famous Jew in the world. Einstein, who had not visited the Middle East for 30 years, did not want to become president of Israel. But his official rejection of the honor was telling.

In a letter to the Israeli prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, Einstein wrote that he was “deeply moved” by the offer of the presidency and that he was disappointed at having neither the experience nor the skills to be able to accept.

Then, in a flourish that underlined his bond with the Jewish people, he concluded, “I am the more distressed over these circumstances because my relationship to the Jewish people has become my strongest human bond, ever since I became fully aware of our precarious situation among the nations of the world.”