In December 2022, the Democratic-led House of Representatives voted to allow Puerto Ricans to decide the political future of the territory, the first time the chamber has committed to backing a binding process that could pave the way for Puerto Rico to become the nation’s 51st state or an independent country.

The measure, which had the support of the White House, did not become law at the time, as it fell short of the 60 votes needed to break a filibuster in the Senate, where most Republicans opposed it.

But the bipartisan vote—the bill passed 233 to 191—according to The New York Times, was a symbolic statement by the House. The legislation would establish a binding process for a referendum in Puerto Rico that would allow voters to choose from among three choices: allowing the territory to become a state, an independent country, or a sovereign government aligned with the United States.[1]

Puerto Rico has been an American territory since 1898, following the Spanish-American War.

Puerto Rico’s 3.3 million residents are U.S. citizens but do not have voting representation in Congress and cannot vote in presidential elections.

They do not pay federal income tax on income earned in Puerto Rico and are not equally eligible for some federal programs.

Puerto Rico itself has held six plebiscites on whether it should become a state, most recently in 2020, when 52% of voters on the island endorsed the move.

None of the plebiscites has been binding, however, and turnout has often been low, amid boycotts by critics who support the status quo or independence.

Solidarity Across the Americas

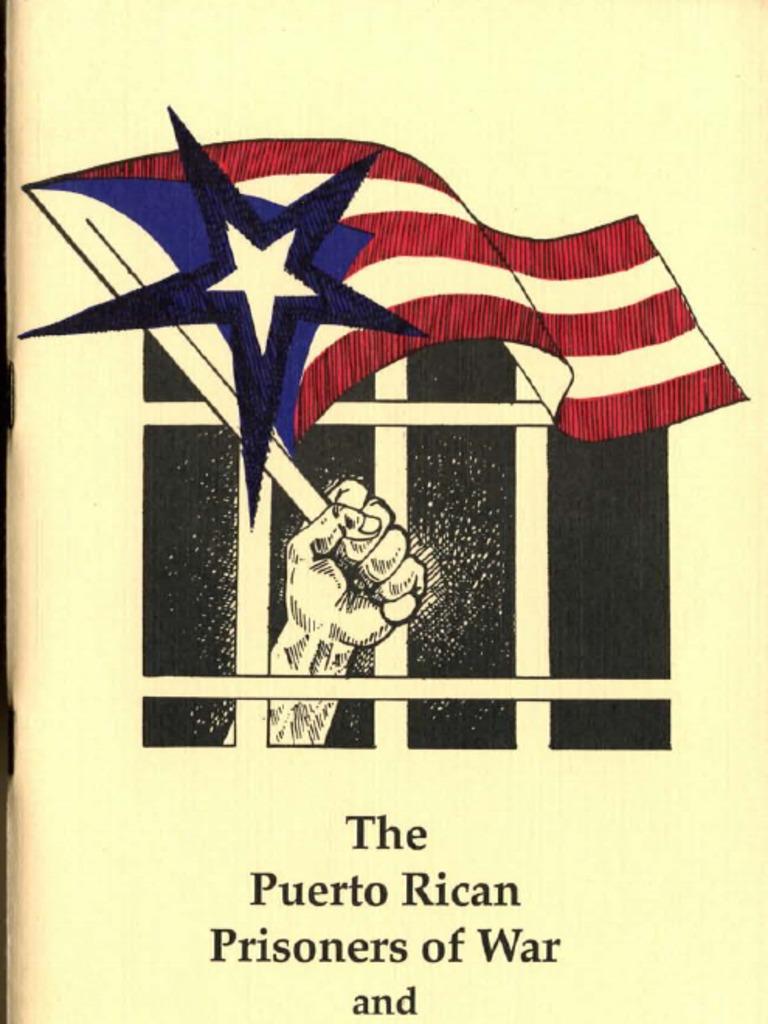

Margaret M. Power’s new book, Solidarity Across the Americas: The Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and Anti-Imperialism, sheds considerable light on the history of the Puerto Rican independence struggle.

Power shows the evolution of the movement and the repression that its supporters faced as well as the solidarity networks that were forged with it across Latin America and among progressive anti-imperialists in the United States.

Power, a professor of history emerita at the Illinois Institute of Technology, is on the Steering Committee of Historians for Peace and Democracy and has previously written a book on right-wing women in Chile.

She starts Solidarity Across the Americas by recounting an incident on March 1, 1954, when Lolita Lebrón and three other members of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party opened fire from the spectators’ gallery of the U.S. House of Representatives after unfurling a Puerto Rican flag and chanting “Viva Puerto Rico Libre!”

Five congressmen were wounded in the shooting though none died.

Lebrón and her comrades—Rafael Cancel Miranda, Andrés Figueroa Cordero and Irvin Flores—were subsequently arrested and tried and convicted of “assault with intent to kill” and “assault with a deadly weapon.” The three men received sentences from 25 to 75 years while Lebrón was sentenced to 16 years.[2]

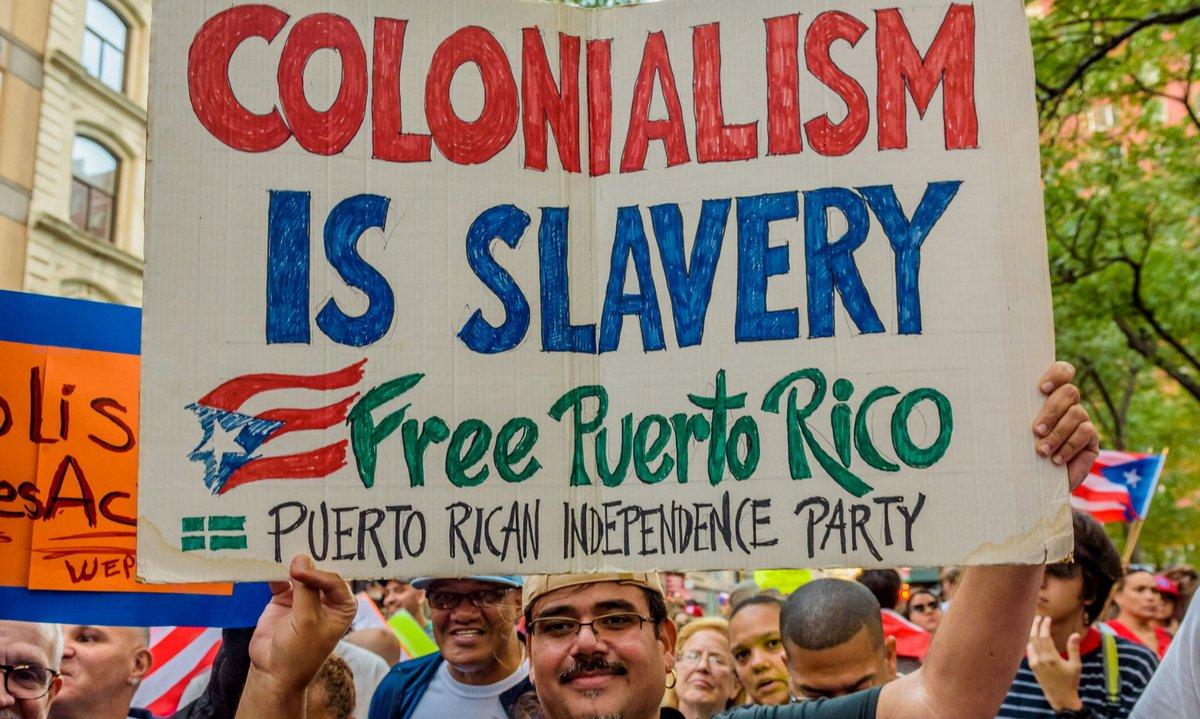

The goal of the attack had been to bring world attention to Puerto Rico’s status as a U.S. colony.

Lebrón had been named as a leader of the attack by Pedro Albizu Campos, the President of the Nationalist Party and a legendary figure in the Puerto Rican independence struggle.

When Power asked Lebrón years later why they had attacked the U.S. Congress, she said that the attack was planned to “coincide with the meeting of the Organization of American States in Caracas.”

The four wanted the people of the Americas to know there were Puerto Ricans who wanted independence and were willing to sacrifice their lives to get it.[3]

Power wrote that Lebrón’s words helped her to appreciate the Nationalist Party’s efforts to gain continent-wide solidarity for the independence struggle.

Their cause was supported by leftists like Guatemalan leaders Jacobo Árbenz and Juan José Arévalo, Cuban revolutionaries Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, and Salvador Allende in Chile. It was also supported by American writers Norman Mailer and Pearl Buck, labor leader A. Philip Randolph, Earl Browder, Secretary General of the Communist Party USA, peace activists like A.J. Muste and David Dellinger, and members of the pacifist Harlem Ashram.[4]

The revolutionary hymn of the Puerto Rican nationalist movement, La Borinqueña—a stirring call to machetes, the agricultural tool that Puerto Rican peasants possessed and could easily employ as weapons—was written by Lola Rodríguez de Tió, a key figure in Puerto Rico’s struggle for independence in the 1880s against Spanish colonial rule.[5]

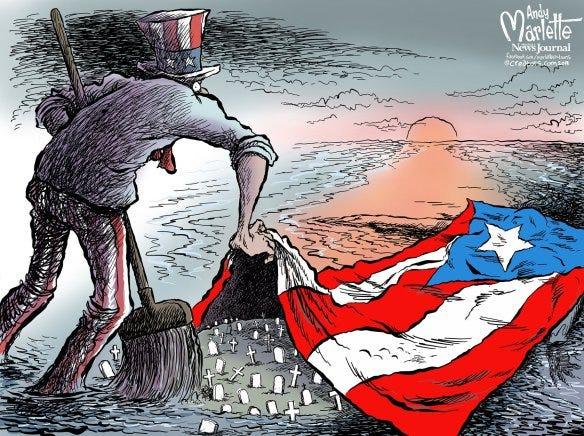

When the U.S. seized Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898, it turned it into a U.S. military outpost.

Puerto Rico offered the United States a key beachhead in the Caribbean. The U.S. Navy used the island of Culebra (a small island off Puerto Rico) for amphibious landing practice and the FDR administration built a mammoth naval base on Puerto Rico’s east coast and the island of Vieques during World War II as part of an attempt to “control the Caribbean Sea.”[6]

During the Cold War, Puerto Rico’s tropical location was an ideal environment in which to train U.S. troops or agents that were later deployed to Korea or Vietnam or participated in the overthrow of President Árbenz of Guatemala in 1954, the invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs in 1961, the invasion of the Dominican Republic in 1965, and the invasion of Grenada in 1983.[7]

According to Power, U.S. rulers justified their governing Puerto Rico by infantilizing Puerto Ricans and declaring them unfit to run their own country.

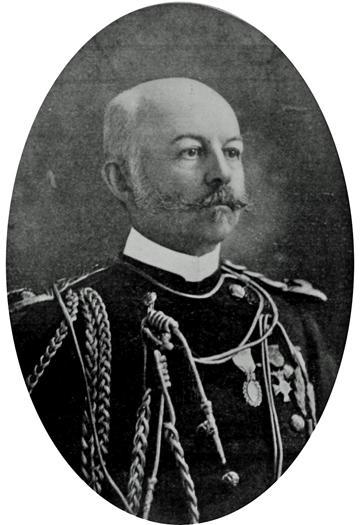

Major Alfred C. Sharpe, Inspector General of U.S. Volunteers in Puerto Rico, compared Puerto Ricans favorably to “wild animals and savage tribes” that roamed New Mexico and Arizona before U.S. “acquisition of these lands.”[8]

The first U.S. governor, Charles H. Allen, built roads at double the cost when the country didn’t have schools, and redirected the country’s budget to no bid-contracts for U.S. businessmen, doled out railroad subsidies for U.S. owned sugar plantations and awarded high salaries to U.S. bureaucrats in the island government.[9]

From 1900 to 1946, when President Harry S. Truman named Jesús T. Piñero governor, no Puerto Rican held that position.

Puerto Rico had a resident commissioner in the U.S. Congress who could voice his (and much later her) opinions but had no right to vote on any issue, even one that affected the archipelago.

In 1948, the U.S. government authorized Puerto Ricans to vote for their governor, and Luis Muñoz Marin of the Popular Democratic Party became the archipelago’s first elected head of government.

Puerto Rico at this time, however, remained a U.S. colony, albeit what Power calls a “camouflaged one,” as Washington continued to exercise control over all key decisions affecting Puerto Rico’s status, economy, political structures and relations with other countries.[10]

Pedro Albizu Campos charged that Muñoz Marin’s party represented “the new theory of colonialism by consent.”[11]

A reason for the latter was that U.S. capital had penetrated most economic enterprises across the archipelago and the government depended on it to finance social programs.[12]

Puerto Ricans became dependent on U.S. products and developed a consumer culture along with a colonial mentality in which they believed that American products were better than Puerto Rican ones.[13]

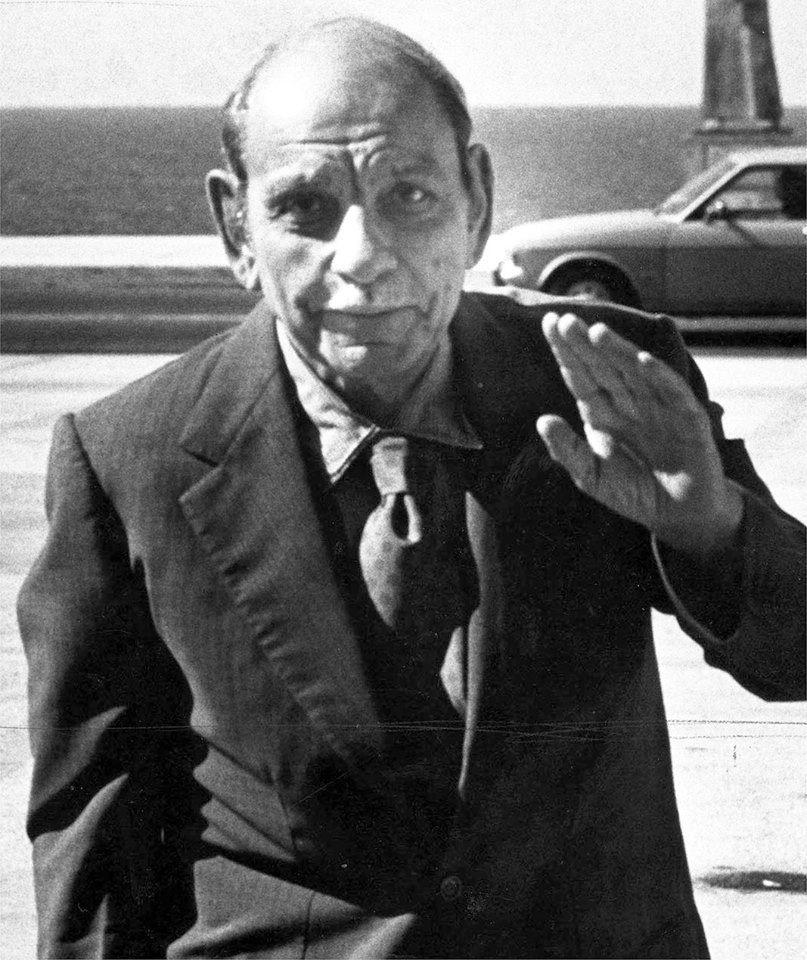

Considered the last of the Hispaniola liberators, Albizu Campos followed from Rodríguez de Tió as the magnetic leader of Puerto Rico’s Nationalist Party from the 1930s through his death in 1965.

Power quotes from a stirring speech that Albizu Campos gave at a nationalist parade in San Juan in 1926 when he removed the U.S. flags on display, stating that in Puerto Rico the U.S. flag represented “piracy and pillage.”[14]

Point 1 of the Nationalist Party platform under Albizu Campos’s leadership was a pledge to organize the workers so they could “recover their share of the profits appropriated by foreign interests.”

Point 2 called for the destruction of latifundismo (landed estates) and absentee land ownership and divisions of land and buildings among small landowners.

Points 5 through 7 spoke to the need to further reorient the economy so that agricultural production, exports, shipping, and the banking system would function to satisfy the needs of Puerto Rico, not U.S. capitalists.[15]

In 1929, Rafael Hernández, one of Puerto Rico’s foremost musicians, composed “Lamento Borincano” which told the story of a jibaro who transports his products to the city, hoping to sell them, but finds only poverty and returns home with the goods unsold.

The song presented a dismal picture of life in Puerto Rico after 30 years of U.S. rule with the disappearance of the rural population’s lifestyle and livelihood due to U.S.-backed monopolization of the land and industrialization.[16]

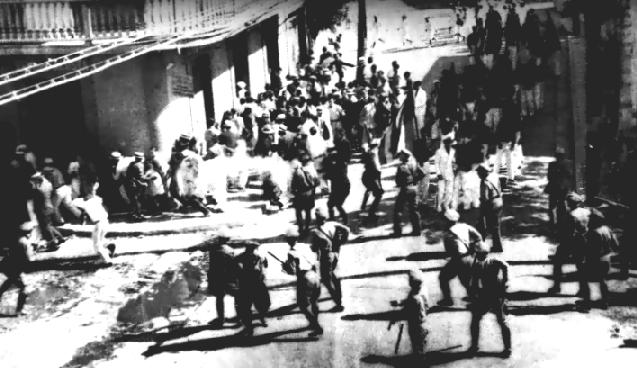

In March 1937, General Blanton Winship, the U.S.-appointed Governor of Puerto Rico who was nicknamed the “sinister shadow” in local media, ordered the chief of police to stop a group of nationalist marchers in the town of Ponce.

When marchers ignored police orders not to advance, the police opened fire, killing 19 and wounding about 200 people in one of the largest police massacres of unarmed citizens in U.S. history.[17]

Eleven years after the Ponce massacre, in March 1948, the FBI declared Puerto Rico’s Nationalist Party to be a “subversive organization,” marking its members as a target of government repression.

FBI surveillance of the nationalists had begun in 1936 and was so widespread that many Puerto Ricans feared that any association with the nationalists would lead to government harassment or worse, the loss of work and/or social, economic and political ostracization.[18]

Nationalist leaders like Albizu Campos were imprisoned, often for long periods, and numbers were assassinated.[19] Police routinely conducted unwarranted searches of Nationalists’ homes and violated their habeas corpus rights.[20]

Nationalist prisoners were often subjected to inhumane conditions that included being fed food with worms in it, being allowed to bathe only once every 22 days and, in the case of Lolita Lebrón, being raped.[21]

Albizu Campos was among those subjected to torture; it left him physically debilitated and, according to his cellmate, he was subjected to electronic experiments by the U.S. Army.[22]

Power discussed how the American Communist Party and solidarity networks in New York City—which contained a huge Puerto Rican population—staged protests and other events in solidarity with Puerto Rican political prisoners and to raise funds for their legal defense.

Harlem Congressman (and avowed socialist) Vito Marcantonio played an influential role throughout the 1940s in sponsoring bills in favor of Puerto Rican independence while advocating for the rights of Puerto Ricans.

In October 1950, armed units of the Liberation Army of the Nationalist Party launched an island-wide rebellion against U.S colonial rule during which Nationalists held the town of Jayuya for three days.

By November 2, army and police units had suppressed the uprising—which Muñoz Marin characterized as a “criminal conspiracy committed by a group of fanatics”—and arrested more than a thousand Puerto Ricans.

The latter included Blanca Canales, a Nationalist leader who had declared the Republic of Puerto Rico after unfurling a Puerto Rican flag at the Palace Hotel in Jayuya.[23]

The Jayuya rebellion coincided with a failed assassination attempt carried out by two Puerto Rican nationalists (Griselio Torresola and Oscar Collazo) against Harry S. Truman, and then four years later, by the shooting in the U.S. House chamber.

Blaming the latter attacks on the “reds,” authorities moved to arrest Nationalist Party leaders who were accused of engaging in a seditious plot to overthrow the Puerto Rican government by force.[24]

Now viewed as a heroine in Puerto Rico, Lolita Lebrón told Power that, although she now considered herself a pacifist, she felt that her actions at the time had been necessary because, “if people had not been willing to give their lives for their patria or there had been no political prisoners, there would be nothing and we would not have accomplished anything. These things inspire and sustain a cause.”[25]

Lebrón’s remarks resonate today where the long-held dream of Puerto Rican independence seems to be finally within reach.

The legitimacy of U.S. colonial rule has been further eroded by a deepening economic crisis; the establishment of an oversight board by the U.S. Congress in 2016 to restructure Puerto Rico’s economy; and the indifference of the U.S. government to Puerto Rican suffering following devastating hurricanes.

In a November 2020 referendum, a majority of Puerto Ricans cast ballots in favor of statehood. ↑

Margaret Power, Solidarity Across the Americas: The Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and Anti-Imperialism (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2023), 1. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 2. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 8, 9. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 22. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 42, 132. The people living on Vieques—much like years later in Diego Garcia—were evicted in order to make way for construction of the base. Power notes that, by 1945, the U.S. military operated more than 30 installations in Puerto Rico, including air fields, naval bases, forts, supply and storage stations, and camps. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 42. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 13. ↑

Gabriela Gavrilova, U.S-Russian Commercial Relations 1763-1933 (self-published, 2024), 199. Allen had a background on Wall Street and formed the American Sugar Refining Company, a syndicate which by 1907 was the largest sugar syndicate in the world. Allen was appointed by Elihu Root, U.S. Secretary of State in the early 1900s who helped solidify U.S. economic control over Puerto Rico, by authoring the Foraker Act. Root was a Wall Street lawyer contemptuous of radical labor groups and an ardent imperialist who championed the U.S. colonization of the Philippines and Cuba also, and U.S. intervention in World War I. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 155. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 160. ↑

Power emphasizes that the most dynamic sectors of the Puerto Rican economy were sugar, tobacco and needlework. By 1927, Power writes that U.S. investors owned 27% of Puerto Rico’s wealth. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 160. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 34. Campos’s predecessor Federico Acosta Velarde had defined Puerto Rico as an “exploited colony,” stating that “we are like a sugar factory for Wall Street, with all the duties and none of the rights.” (p. 74). ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 102. The Nationalists also opposed U.S. militarism in Puerto Rico and called on Puerto Ricans not to enlist in the U.S. military. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 50. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 97. A veteran of the Spanish-American Philippines War and Silver Star recipient in World War I from Macon, Georgia, Winship was considered the U.S. Army’s top lawyer in the 1930s. Following a fact-finding mission by avowed socialist Congressman Vito Marcantonio, FDR dismissed Winship on May 12, 1939. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 13. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 133. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 174. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 174, 175, 197. The cells of many prisoners were lit up 24 hours per day. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 175, 176. The U.S. government labeled Albizu Campos as “crazy” and a “fanatic” in order to dismiss his allegations and the cause for which he was fighting. Dr. Orlando Duarney, President of the Cuban Cancer Association and an expert on radiation, examined Albizu Campos after his release from prison in 1953 and determined that his injuries were produced by radiation. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 169. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 185. ↑

Power, Solidarity Across the Americas, 197. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.

The Republicans would not want Puerto Rico to become the 51st state. On November 5, 2024 Puerto Rico had a symbolic vote in the US election. 57 % of the population participated in this vote and 73.4 % voted for Kamala Harris and 26.6 % voted for Donald Trump. But Puerto Ricans are not allowed to vote in the American election, so this was just a symbolic exercise.