During his inaugural address, Donald Trump said that he would “restore the name of a great president, William McKinley,” who “made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent—he was a natural businessman—and gave Teddy Roosevelt the money for many of the great things he did including the Panama Canal.”

McKinley also sent U.S. troops to fight in the Spanish-American War resulting in the acquisition of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines under the fraudulent pretext that Spain had sunk the USS Maine in Havana Harbor.

McKinley claimed to have walked the floor of the White House one night and to have received a vision from God telling him to go out and “educate the Filipinos and uplift and civilize and Christianize them and by God’s grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died.”[1]

Like all colonial powers, self-righteous rhetoric was accompanied by brutal massacres carried out in this case by U.S. troops who foreshadowed their counterparts in the Vietnam War by referring to the Filipinos as “gooks.”

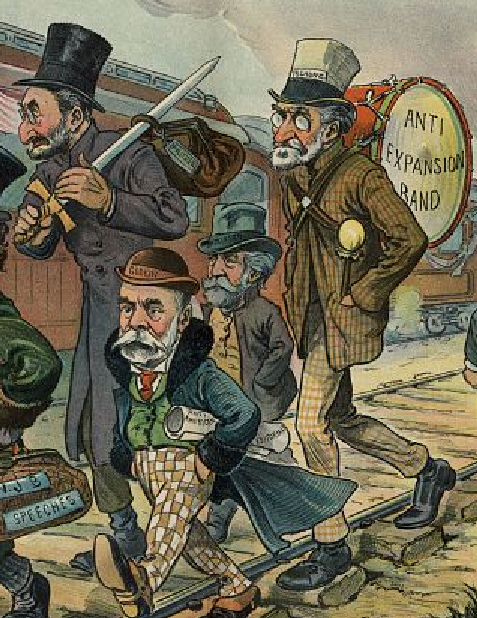

Trump’s lionization of a turn-of-the-20th-century war criminal provides an opportunity for progressives to reignite the spirit of the Anti-Imperialist League, which was founded by Americans who opposed the birth of an overseas U.S. empire under President McKinley.

Since the Vietnam War ended, the U.S. anti-war movement has often been limited in its approach of trying to mobilize the public against this or that particular war.

What is needed is a permanent national organization that tries to mobilize the population not just against war but also empire, including through a program of political education.

That was the approach of the Anti-Imperialist League, which considered the U.S. acquisition of overseas colonies and militarism to be antithetical to American democratic principles as laid out in the Declaration of Independence.

Republic or Empire?

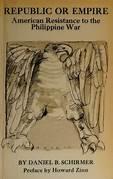

In 1972, Daniel B. Schirmer published an excellent study of the Anti-Imperialist League, Republic or Empire? American Resistance to the Philippine War, with a preface by famed radical historian Howard Zinn.

Zinn compared the Philippines War with the Vietnam War, noting the use of “‘trumped up incidents’ to launch both wars; the disgust of U.S. soldiers with the war, the look beyond the battlefield to the markets of China,” and the “ignoring of peace overtures from the other side.”

Further, Zinn emphasized how the “poverty of historical education in the U.S.” led most people to neglect the continuity across time with regards to U.S. foreign policy, and to forget about the Anti-Imperialist League, which was a direct forerunner of the 1960s anti-Vietnam War movement.[2]

Schirmer emphasized that the Anti-Imperialist League was headquartered in Boston, Massachusetts—then a liberal city at the heart of the anti-slavery movement and where utopian socialism and other reform movements had flourished.[3]

The League’s founding meeting took place at Boston’s historic Faneuil Hall in June 1898.

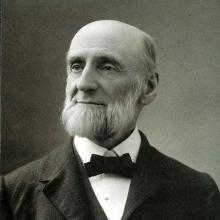

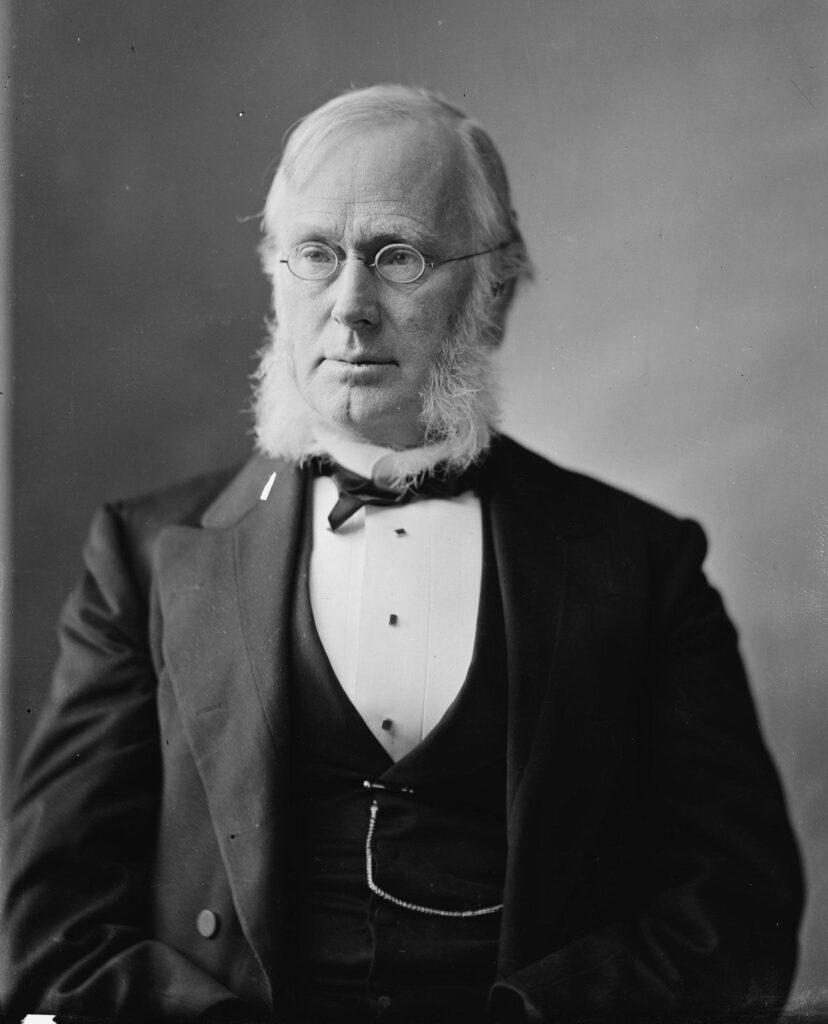

The first head of the organization, Gamaliel Bradford, was a Mayflower descendant and political reformer whose father had been a leader in Boston’s abolitionist movement.

Though a banker by profession, Bradford sympathized with organized labor and wrote an 1898 book, The Lesson of Popular Government, which warned that “the great trusts and monopolies which have sprung up through the country are leaving more and more that they have only to bring together sufficient money power to work their will with Congress.”[4]

Bradford’s populist outlook was shared by many other members of the Anti-Imperialist League, which had wide support among Boston’s merchant association. Schirmer explained that most of Boston’s merchants opposed McKinley’s tariff policy as they were proponents of free trade and were uneasy with the shifting trend in the U.S. economy toward manufacturing.

Manufacturing business owners largely supported President McKinley and other pro-imperialists in Congress because they favored his tariffs and saw great opportunity with the opening of foreign markets by the U.S. military.

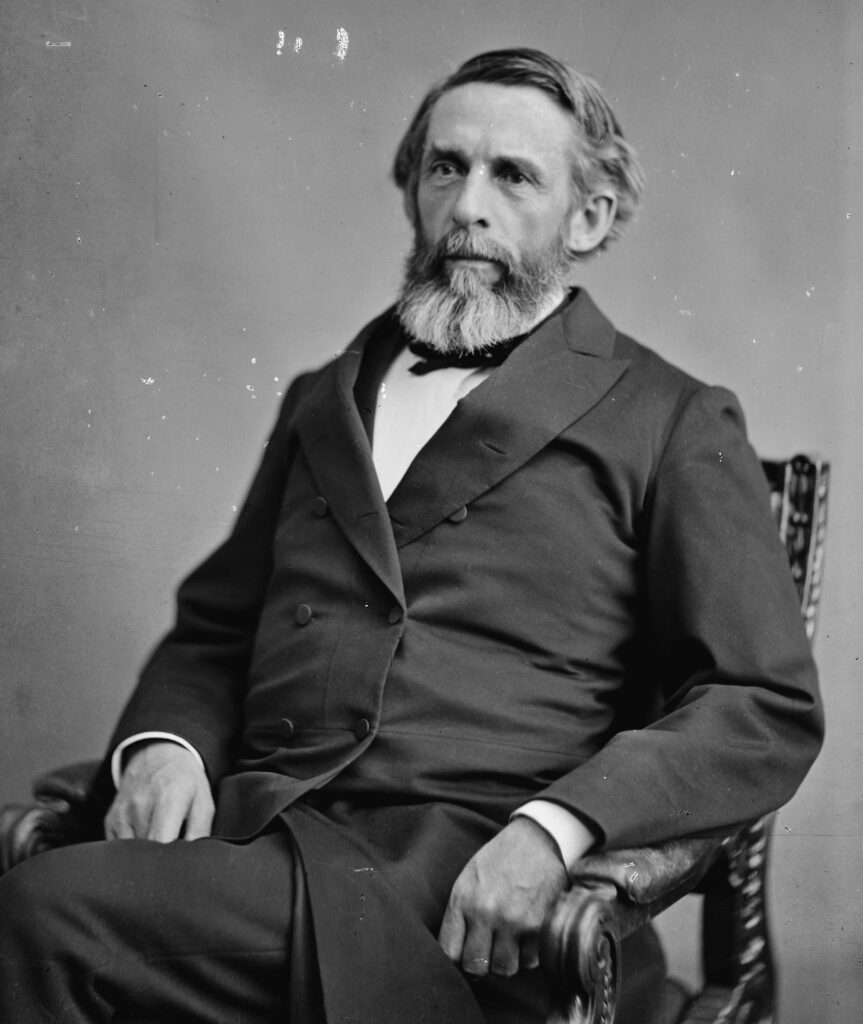

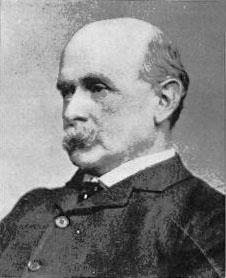

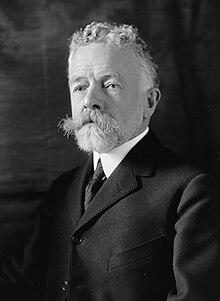

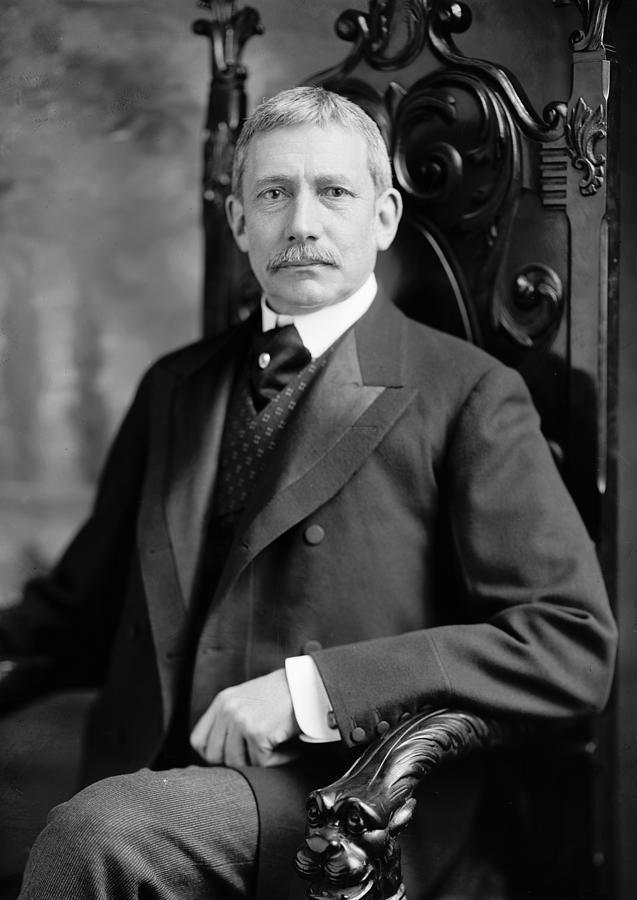

The first president of the Anti-Imperialist League, George Sewall Boutwell, former Treasury Secretary under Ulysses S. Grant and Massachusetts Governor, had been a close associate of Abraham Lincoln, who had opposed the U.S.-Mexican War.

Boutwell and others in the Anti-Imperialist League believed that the U.S. was founded as a republic in opposition to the British empire and that the Filipinos were justified in fighting for their national independence—as George Washington’s Continental Army had been in fighting the British.

Some in the Anti-Imperialist League equated U.S. policy in the Philippines and Cuba with that of Spain and the British intervention in South Africa in the Boer War. Others pointed to the precedent of the seizure of Indian lands in the U.S. and inglorious war of conquest with Mexico.

While averse to organizing acts of civil disobedience or protests, League members would arrange speaking events, produced and distributed leaflets, issued press releases, and initiated a mass petition campaign against extending U.S. sovereignty over the Philippines.

By February 1899, the executive committee estimated League national membership to be “considerably over 25,000.” Branches were established in 40 cities across the U.S.[5]

Boston’s Unitarian minister Charles Fletcher Dole embodied the religious underpinning of the movement, preaching that war and empire violated Christ’s doctrine of the brotherhood of man.[6]

During the 129th commemoration of the death of Crispus Attucks, whose death at the hands of British troops helped trigger the American Revolution, African-American supporters of the Anti-Imperialist League gave speeches in Boston denouncing Anglo-American colonialism and stating that they opposed killing Filipinos because they were “fighting for just what our forefathers sought 35 years ago [in fighting against slavery during the Civil War].”

Supporters of the Anti-Imperialist League included Robert Paine, Jr., Thomas Paine’s great- great-grandson and Charles Francis Adams, Jr., John Quincy Adams’ grandson and John Adams’ great-grandson, who was scornful of “the prattle about the white man’s burden and lifting up of inferior races,” according to historian Robert L. Beisner.[7]

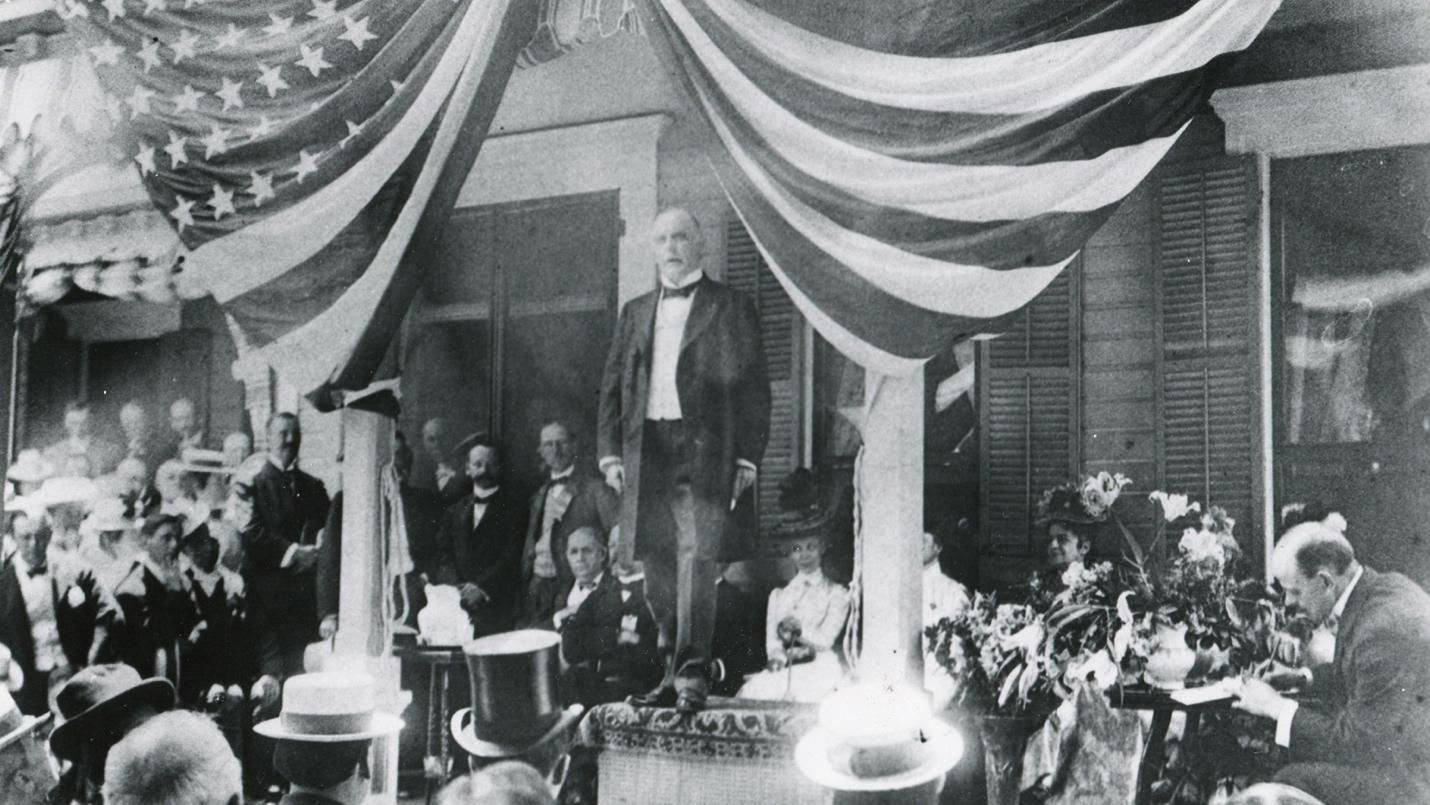

Additional members included former Presidents Grover Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison; Boston Mayor Patrick Collins (1901-1905); and Harvard University President Charles William Eliot who tried to ban football from campus because of the warlike nature of the game, and declared before an audience in Cambridge, MA that America’s “rash eagerness for a totally unnecessary war was a turning back from the path of civilization to that of barbarism….to wage such a war was a national crime.”[8]

Eliot was attacked for his views in The Chicago Tribune, which accused him of “trying to kill the generous impulses of patriotism and to besmirch the noble cause of humanity upon which the war against Spain is based.”[9]

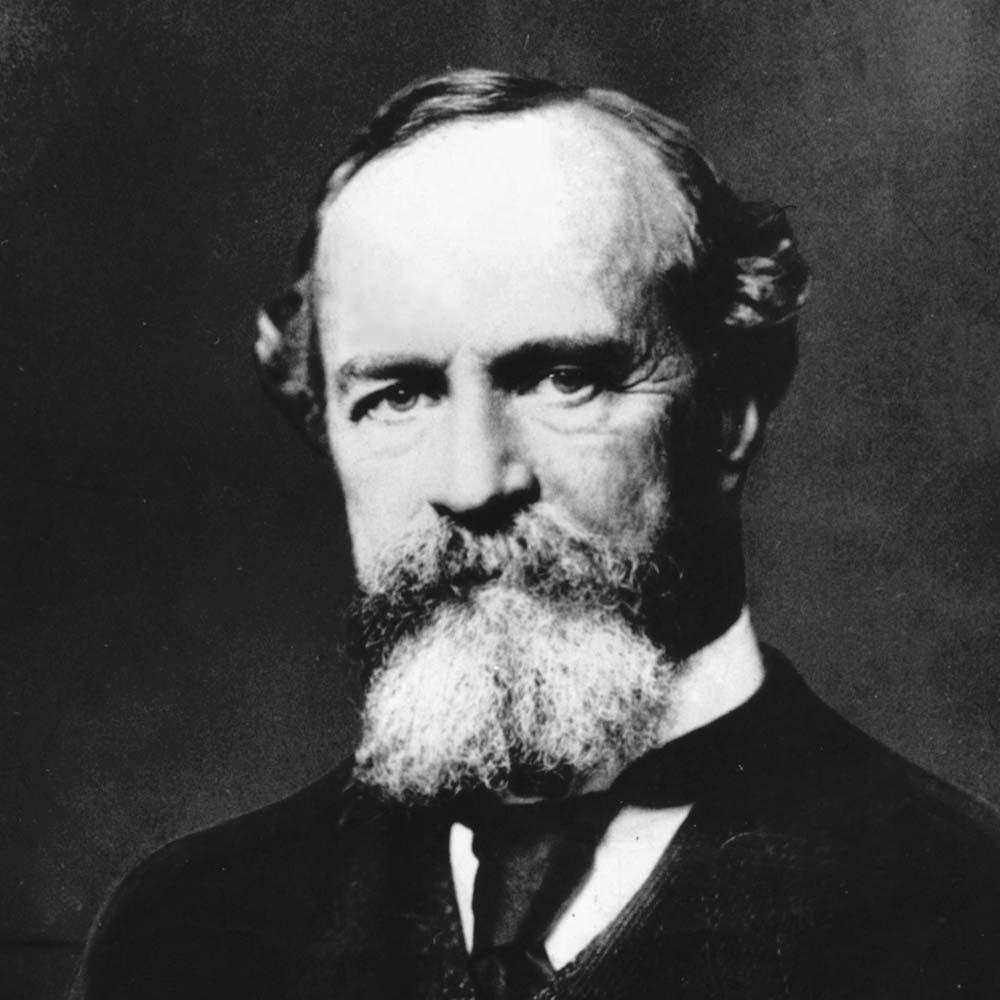

Eliot’s star professor at Harvard, William James, the “father of modern psychology,” joined him in the Anti-Imperialist League. James considered U.S. policy in the Philippines to be little more than “brutal piracy.”

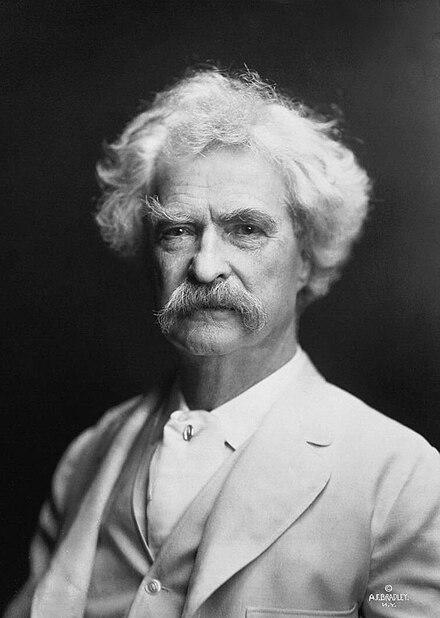

The greatest man of letters of Gilded Age America, Mark Twain, shared a similar outlook. He mocked McKinley’s self-righteous rhetoric used to sell the Philippines’ war, declaring “we have pacified some thousands of the islanders and buried them, destroyed their fields, burned their villages, created widows and orphans and subjugated the remaining ten million by benevolent assimilation [word used by President McKinley to describe U.S. endeavors in Philippines]—which is the pious new name of the musket!”[10]

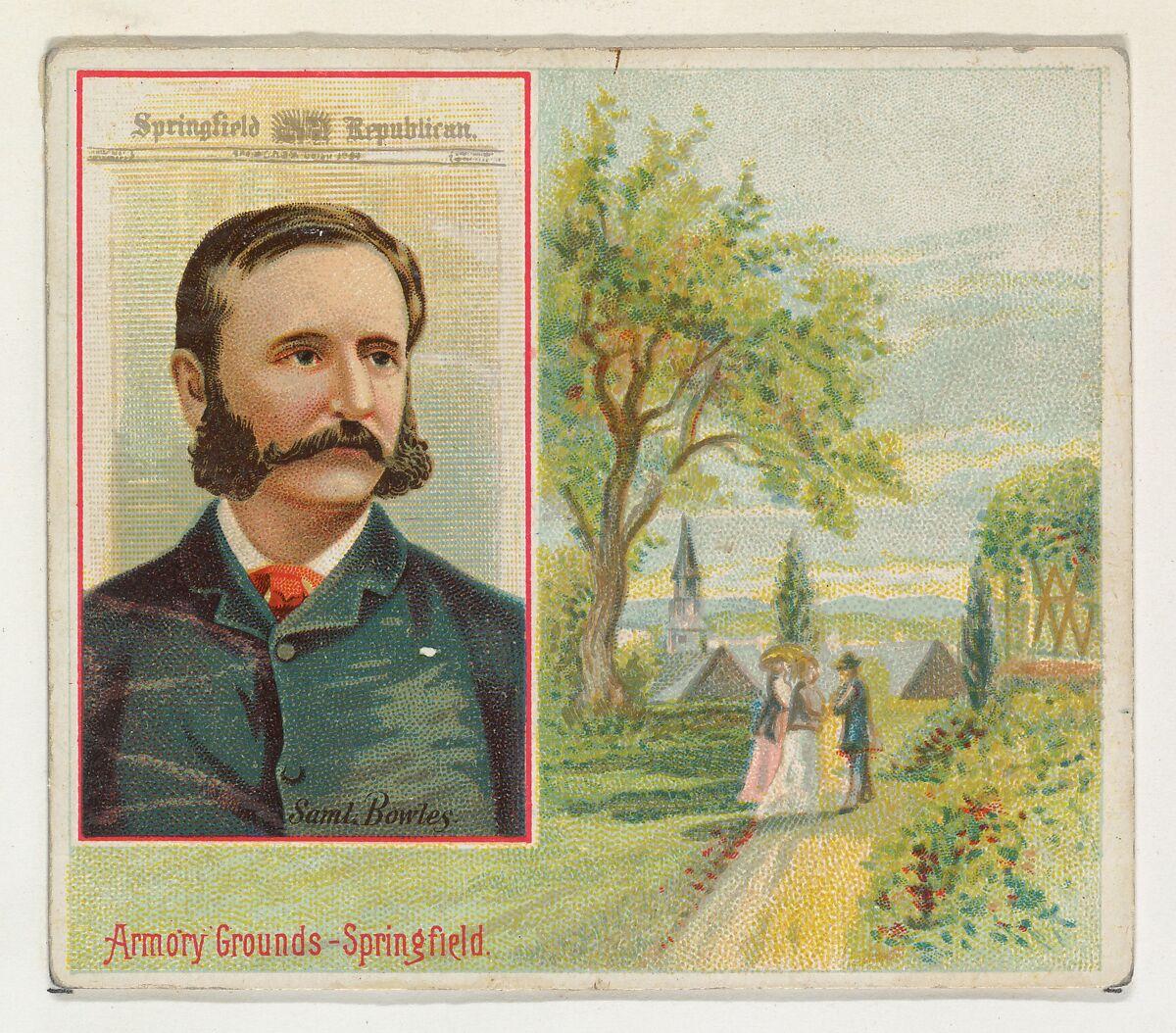

Unlike today where anti-war views are censored, many Massachusetts newspapers—including the Boston Herald and The Boston Post—offered them a platform. Springfield Republican editor Samuel Bowles wrote that the lust for empire was being driven by what he called “incorporated and syndicated wealth.”[11]

This kind of political-economic analysis—later adopted by CovertAction Information Bulletin founder Philip Agee—may be considered radical today, though it was standard at the time.

The Boston Herald editorialized that McKinley’s war policy “delighted the hearts of the speculative capitalists” who were recognized to be behind U.S. expansionism.

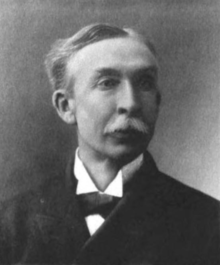

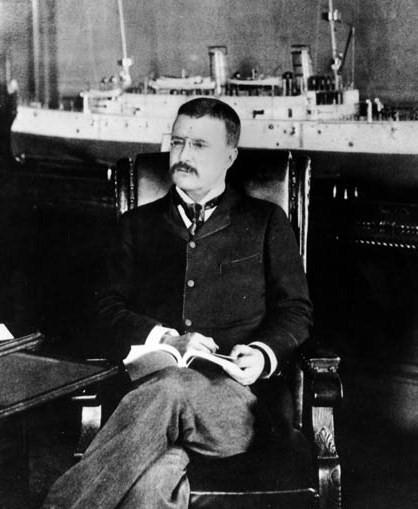

A key foe of the Anti-Imperialist League was Massachusetts Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (1893-1924). A good friend of Theodore Roosevelt, Lodge was a proponent of naval rearmament who advocated for the opening of foreign markets in Asia to U.S. manufacturers and zealously supported the Philippines War.

Massachusetts’ senior senator, George Frisbie Hoar, broke from Lodge and pushed an international plan with another Anti-Imperialist League supporter, Senator Carl Schurz (R-MI), that would guarantee Philippines’ sovereignty as a nation.[12]

In the 1900 election, many anti-imperialists supported Democrat William Jennings Bryan, the former head of the Populist Party who warned in a campaign speech that “imperialism would require a large standing army” and “encourage more wars of conquest” while “turning the thoughts of our young men from the arts for peace to the science of war.”[13]

This kind of rhetoric invited attacks from militarists of the era, like Theodore Roosevelt, who inveighed against Bryan’s alleged promotion of “communistic doctrines.”

In 1901, Roosevelt described anti-imperialists as “unhung traitors and liars, slanderers, and scandalmongers.”[14]

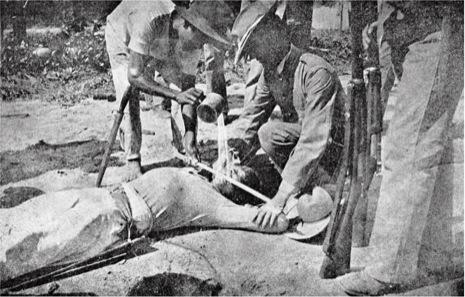

Dissension over the Philippines war increased as U.S. troops became bogged down in a quagmire and were exposed torturing Filipino captives, contradicting Secretary of War Elihu Root’s claim that the U.S. was conducting the war “with scrupulous regard for the rules of civilized warfare.”

General Arthur MacArthur wrote in an October 1900 report that U.S. military failures could be attributed to “the almost complete unity of action of the entire native population”—much like in Vietnam 60 years later.

The Anti-Imperialist League helped ignite further anti-war opposition when it published a pamphlet of soldiers’ letters that provided what Schirmer called a “record of racism and slaughter.”

A Captain Elliott from the Kansas Regiment wrote in one of the letters that “Caloocan [outside Manila] was supposed to contain 17,000 inhabitants. The 20th Kansas swept through it, and now Caloocan contains not one living native. Of the buildings, the battered walls of the great church and dismal prison alone remain.”

A private quoted in the pamphlet made reference to a “goo-goo hunt,” while another soldier from Washington State was quoted stating that soldiers in his regiment all “wanted to kill niggers. This shooting human beings beats rabbit hunting.”[15]

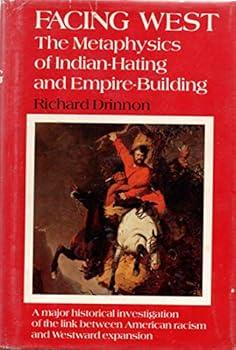

Historian Richard Drinnon pointed out that members of the Anti-Imperialist League were prone to idealize the American past and sometimes embraced dominant racist attitudes while opposing colonization only in specific contexts, or because it would result in immigration of darker races to the U.S. Some supported an informal American empire rooted in commercial expansion and not formal rule over others. Drinnon nevertheless concedes that the anti-imperialists were courageous “to stand in front of the onrushing empire.”[16]

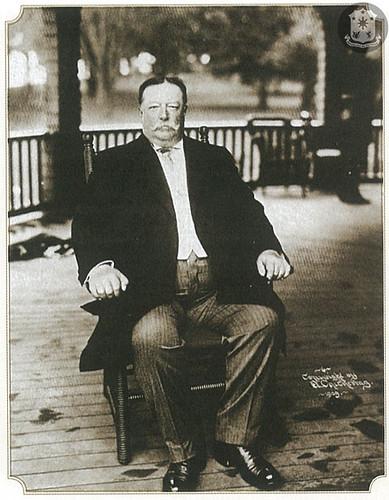

At the 1904 Harvard graduation, William Howard Taft, the future U.S. president, then-Secretary of War, and who served as Governor-General of the Philippines from 1900 to 1903, told reporters that “the anti-imperialists had served as a check upon us.”[17]

These latter comments make clear the positive impact of the Anti-Imperialist League, which contributed to the Roosevelt administration’s decision to withdraw U.S. troops from the Philippines in 1902. The League in turn helped shape the subsequent light footprint strategy of building up a Filipino constabulary to complete the pacification started by U.S. troops.[18]

Thereafter, the U.S. became more of an “informal empire,” eschewing direct colonization and military occupation, for the most part, in favor of covert forms of intervention and soft-power approaches.[19]

While the latter have often been cataclysmic—as CovertAction Magazine and its predecessor Covert Action Information Bulletin have long detailed—there has been some evolution in that direct forms of colonialism have been repudiated.

Today, there is an urgent need for formation of a new Anti-Imperialist League in light of the world situation and the Trump administration’s praise for McKinley and jingoistic rhetoric.

The lack of contemporary debate over U.S. imperialism in the halls of Congress is a symptom of decaying democracy that members of the Anti-Imperialist League had warned would be a consequence of imperialism.

The new League ought to invoke some of the voices of the past in staking out a position against empire in all of its modern-day incarnations and horrors.

See https://peacehistory-usfp.org/1898-1899/ ↑

Daniel B. Schirmer, Republic or Empire? American Resistance to the Philippine War (Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Publishing Company, 1972), with Preface by Howard Zinn, ix, x. ↑

Schirmer presents the Anti-Imperialist League as a successor of the abolitionist movement, which was also supported by Boston brahmins and middle-class reformers. ↑

Schirmer, Republic or Empire? 75. ↑

https://peacehistory-usfp.org/1898-1899/; Schirmer, Republic or Empire? ↑

Amazingly, Dole’s son James moved to Hawaii to establish a pineapple-growing empire, which would become Dole Food Company. ↑

Adams’s view, according to Beisner, was that “considering the unchristian, brutal, exterminating treatment the Indians had been subjected to by American settlers and the nation’s long, shameful record with Negroes and Chinese, it was ridiculous to think of the U.S. as in any way specially fitted to govern less familiar people.” Robert L. Beisner, Twelve Against Empire: The Anti-Imperialists, 1898-1900 (Chicago: Imprint Publications Inc., 1968), 235. ↑

Eliot quoted in Beisner, Twelve Against Empire, 80. ↑

Beisner, Twelve Against Empire, 237. ↑

See https://peacehistory-usfp.org/1898-1899/; Mark Twain, “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” North American Review, February 1901. ↑

The Boston Globe supported imperialism as it does today. Unfortunately, there are no anti-imperialist papers left in Boston or elsewhere in the country, except perhaps this webzine and a couple of other online magazines like antiwar.com. ↑

See Richard E. Welch, Jr., “Senator George Frisbie Hoar and the Defeat of Anti-Imperialism, 1898-1900,” The Historian, 26, 3 (May 1964), 366. Hoar had voted to support the Spanish-American War and approved the acquisition of Hawaii as a necessary defense measure. ↑

Schirmer, Republic or Empire?; Michael Kazin, A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (New York: Anchor Books, 2007), 103. ↑

Beisner, Twelve Against Empire, 237. ↑

Schirmer, Republic or Empire? 237. A.L. Mumper of the 1st Idaho Regiment stated that racism “leaked down from officers, who impressed on us that the Filipinos were niggers, no better than Indians and were to be treated as such.” Another letter published in the pamphlet read: “The Filipinos’ colored skin invites as much consideration from the proud whites as an animal.” The genocidal nature of the U.S. warfare was further exposed by a Republican congressman who visited the Philippines and reported that “you never hear of any disturbances in Northern Luzon because there isn’t anybody there to rebel. That area was marched over and cleared out in a most resolute manner. The good lord in heaven only knows the number of Filipinos that were put under the ground; our soldiers took no prisoners; they kept no records; they simply swept the country and wherever or however they could get hold of a Filipino, they killed him.” ↑

Richard Drinnon, Facing West: The Metaphysics of Indian-Hating & Empire-Building (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980), 311. Drinnon notes that, when anti-imperialists tried to present U.S. expansion in the Philippines as an aberration in U.S. history, pro-imperialists like Theodore Roosevelt responded by asserting that expansion had been in the country’s DNA since its founding. This latter viewpoint is recognized in Richard Van Alstyne’s book, The Rising American Empire, rev ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1974), which analyzes the writings of the American founding fathers and finds that they were universally expansionist and aspired for the U.S. to become a great empire, eclipsing the Roman or Greek empires at their apex. ↑

Schirmer, Republic or Empire? 240. Taft’s statements contradict the conclusion of historian Fred Harvey Harrington, who wrote that the achievements of the Anti-Imperialist League were “few” and that the League “left no trace in American history.” Fred Harvey Harrington, “The Anti-Imperialist Movement in the United States, 1898-1900,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 22, 2 (September 1935), 211-30. Reflecting a deep nationalistic bias, many other American historians similarly adopted a negative view of the Anti-Imperialist League. Robert L. Beisner, for example, in Twelve Against Empire (p. 232) claims that they were false prophets because “undemocratic modes of U.S. colonial rule did not produce a tyrannical backlash in the U.S.” This viewpoint is contradicted by Alfred W. McCoy’s study, Policing America’s Empire: The U.S., the Philippines and the Rise of the Surveillance State (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009). Beisner also suggests falsely that the Anti-Imperialist League’s critiques and warnings were wrong headed because the U.S. colonial conquests in the Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico “did not lead to an orgy of territorial expansion” and because “American colonial rule was not characterized by incompetence, corruption, brutality and injustice.” Beisner wrote that “perhaps because the U.S. had no vital need to exploit the resources of its colonies, it made a record as imperial master, which compared with traditional European examples, was notably intelligent, restrained and humane.” This view is not born out by the facts, and contradicted in the following essay https://peacehistory-usfp.org/1898-1899/. ↑

See McCoy, Policing America’s Empire. ↑

The concept of informal empire was developed in William Appleman Williams’ classic book, The Tragedy of American Diplomacy (Cleveland, OH: World Publishing Company, 1959). ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.