Recently released documents as part of JFK dump show how CIA took charge of American embassies around the world operating under State Department cover

Revealed in the recent document dump from the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection as mandated by a presidential directive was just how extensively and deeply the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had penetrated into State Department functions.

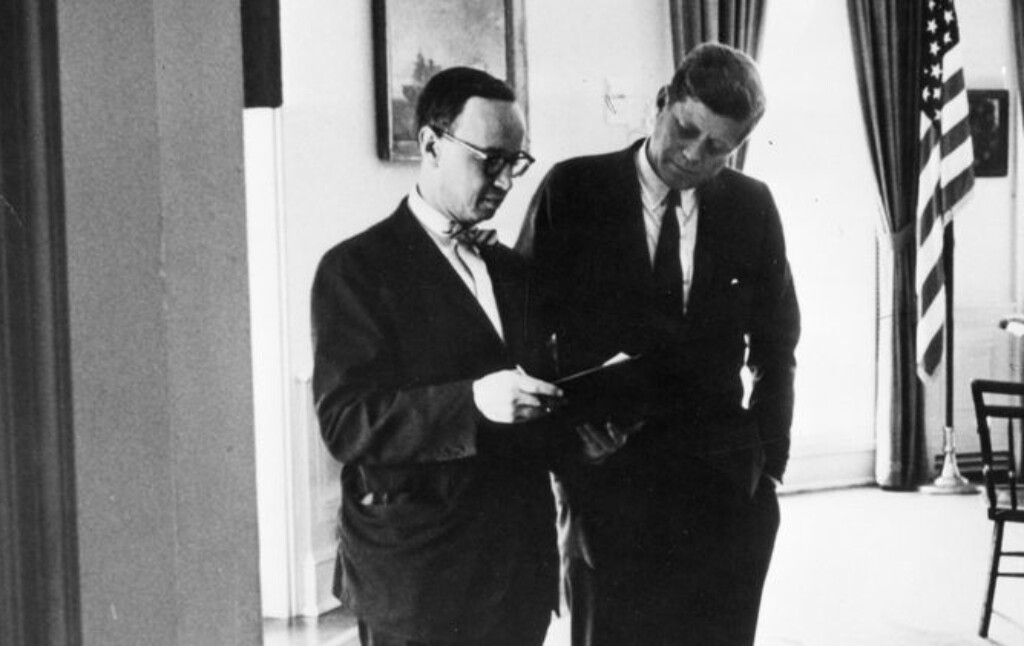

In June 1961, White House aide Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., complained to President John F. Kennedy that the CIA had nearly as many people under official cover in its embassies as were actual State Department diplomats.[1]

Schlesinger cited some stunning figures: In the political section of the U.S. embassy in Vienna, 16 of the 20 people as listed in the October 1960 Foreign Service List, a quarterly State Department publication of personnel assignments, were CIA case officers, as were over half of the 31 officers listed as engaging in reporting activities.

Similarly, 11 of the 13 officers in the political section in the embassy in Chile were CIA. The CIA had 128 people in the embassy in Paris, and they had taken over the political reporting functions that previously was the domain of State Department diplomats. In fact, these CIA officials had begun to monopolize contact with French politicians.

According to Schlesinger, the State Department had about 3,900 officials stationed in other countries, whereas the CIA had 3,700. In other words, almost half of the political officers in U.S. embassies were CIA officials. About 1,500 of those CIA officials were under State Department cover, while presumably the other 2,200 operated under military or other governmental cover.

The CIA euphemistically referred to its case officers stationed in U.S. embassies under diplomatic cover as Controlled American Sources (CAS). The origins of the term “controlled American source” lies in obscurity but, according to the late John Prados from the National Security Archive, it “probably originated as an indicator that information came from a U.S. asset, but it came to be a stand-in for CIA station.” The term formed part of the fiction that the agency attempted to preserve for many decades that there was “no such thing as a CIA station.”

In his memo to Kennedy, Schlesinger traced the CIA’s arrangement with the State Department to use diplomatic cover for its officers as dating back to the agency’s creation in 1947. Originally this was to be a temporary and strictly limited arrangement. The CIA was not supposed to rely on State Department cover as a simple answer to its problem of placing its officers in other countries. Rather, the agency was to establish its own cover arrangements and, in this way, reduce its dependence on the State Department. Nevertheless, the CIA steadily increased its use of official diplomatic cover.

State Department cover offered several advantages for the CIA, which led the agency to abandon its plans to develop its own systems of private, non-official cover. The current arrangement was quicker, easier, more convenient, and more cost-effective for the CIA. It enhanced operational security and communication, and ensured a more comfortable lifestyle for its personnel stationed in other countries than if the agency had made these arrangements itself.

All of this came at the cost of CIA encroachment on State Department functions. Sometimes CIA Chiefs of Station (COS) had been in the country longer than the ambassadors, had more direct access to government officials, had more money at their disposal, and wielded more political influence than diplomatic officials. On occasion, the CIA chief pursued different policy objectives than State Department officials, and even excluded the head of mission from their operational functions. Further undermining this legal fiction, at times it was no great secret who the CIA officers were.

Despite these problems, the CIA remained fully committed to maintaining and expanding its CAS operations as a permanent solution to its problem of how to station its officials in other countries. The agency even pressured the State Department to grant its personnel higher status positions in its embassy.

Schlesinger cautioned that, before the State Department lost complete control over international diplomacy, and before CIA officers became permanently entrenched in the foreign service, it was important to assure that ambassadors re-establish firm control over the CIA stations in their embassies. He suggested that a review be conducted with the goal of gradually reducing CAS personnel in order to restore the State Department’s primary role in diplomacy.

Philip Agee

Half a year before Schlesinger penned his memorandum to Kennedy, the former case officer and CovertAction Magazine co-founder Philip Agee arrived at his first posting in Quito, Ecuador. Agee first appears in the Foreign Service List in January 1961 with his posting as an assistant attaché, political officer in the political section of the Quito embassy—the State Department cover for his work with the agency. His rank was R-8, or Foreign Service Reserve Officer (FSR), a designation commonly used for CIA officers.[2]

Agee’s fellow CIA officers in the political section of the embassy were the Chief of Station (COS) James B. Noland, who was posted on July 14, 1957, and held a rank of R-6, and reports officer John E. Bacon, who was posted on November 29, 1959, with an R-7.

Another CIA operations officer in the embassy was Robert J. Weatherwax, posted as a public safety adviser with the United States Operations Mission (USOM) of the International Cooperation Administration (ICA) program with a rank of R-6.[3] As a newly assigned officer at 25 years old, Agee held the lowest rank—as well as the lowest pay—of the four. The Foreign Service List gives his date of posting as November 9, 1960, although he did not actually arrive in Ecuador until almost a month later. Apparently, this date was that of his formal assignment.

During his time in Ecuador, Agee remained as one of the least important officers not only in the CIA station in Quito but in the embassy as a whole. In an order of precedence among 26 embassy officers and wives from a list distributed in June 1962 after a year and a half at his post, Agee ranked last.[4] Half a year later in November 1962, and after almost two years at his post, Agee still was at the bottom, only beating out third secretary and vice consul, John P. Steinmetz, the assistant consular officer in the consular section.[5]

Steinmetz was a “rotational” FS0-8 who had only arrived in Quito in August. John E. Karkashian, the Ecuadorian desk officer in the State Department in Washington, described Steinmetz “as being a very intelligent and competent young man and should prove to be an asset to the staff.”[6] He was one of only three diplomatic personnel in the embassy who was not married.[7]

The United States Embassy welcomed Agee to Quito—as it did with all of the personnel in the embassy whether they were authentic diplomats or undercover intelligence operatives—with a set of dispatches to the Ecuadorian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A December 12, 1960, letter, coming a week after Agee’s arrival, sought “to inform the Ministry of the arrival on December 6 of Mr. Philip B. F. Agee, Assistant Attaché of this Embassy, who is accompanied by his wife.” The embassy requested “that the usual Diplomatic Cupo be issued to Mr. Agee.” A handwritten note on the letter states “Concedido Cupo Ene. 16/61,” indicating that he would enjoy the same waivers of import duties as any other diplomat.[8]

A second letter three days later provided the Ecuadorian Foreign Ministry with registration information for Agee and his wife Janet. The forms provided Agee’s title (Assistant Attaché), his date of birth (January 19, 1935), and place of birth (Takoma Park, Maryland). The State Department issued both Agee and his wife diplomatic passports on November 17, 1960 (numbers 24356 and 24355 respectively), with the diplomatic visas (numbers 81 and 80 respectively) following on November 21, 1960.[9] As always, the Ecuadorian foreign ministry responded with a formal acknowledgment of the communication.[10]

Two weeks later the embassy asked that the ministry issue diplomatic driver’s licenses and diplomatic identity cards (carnets) to its new “assistance attaché” as well as his wife Janet. The letter included four photographs of each of them as well as physical descriptions (Agee was five feet, eight inches tall with brown eyes, whereas his wife Janet was five feet, five inches tall with hazel-colored eyes; both were aged 25 and had brown hair). Handwritten notes on the letter indicate that the ministry issued the two carnets, numbered 08-61 and 09-61, on January 12, 1961, and driver’s licenses numbers 09-61 and 10-61 a week later.[11]

Agee, as with other CIA case officers, took advantage of their diplomatic privileges to import personal items, including clothes and a Christmas tree.[12] Shortly after his arrival, Agee also imported a little Renault four-door sedan, as the Ecuadorian government permitted others in the embassy, both regular diplomatic staff and CIA case officers, to do.[13] The cars were to be for personal use, and not immediate resale. When Agee sold the car two years later, he received a waiver so as not to be charged customs duties.[14] The case officers also regularly imported liquor and other such luxury items, presumably for their agents and other assets.

Several months into Agee’s tour of duty in Ecuador, embassy counselor Edward S. Little wrote to Ecuador Foreign Minister José Ricardo Chiriboga Villagómez, asking permission to import tax free “1 paquete: conteniendo ropa interior de seda para señora y lápiz labial, para uso del señor Philip B. Agee,” one packet containing ladies’ silk underwear and lipstick, for the use of Mr. Philip B. Agee.[15] Was this for his wife Janet’s use, for a bribe for a CIA agent, or something else entirely?

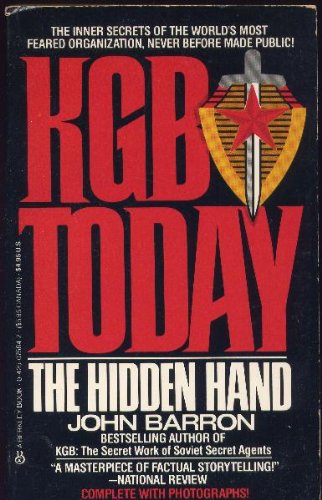

Salacious and slanderous rumors have long swirled around Agee that he was a “womanizer.” Most famously, in a hatchet job on the former case officer, journalist John Barron charged in his book KGB Today that the CIA forced “Agee to resign for a variety of reasons, including his irresponsible drinking, continuous and vulgar propositioning of embassy wives, and inability to manage his finances.”[16]

Barron’s statement was part of a broader attack that the agency launched against him. One document that the CIA released in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request states: “During his Agency career Agee showed himself to be an egotistical, superficially intelligent, but essentially shallow young man who was uninterested in politics and had no political convictions. If anything, his political orientation was right-wing conservative.”[17] Agee, of course, denied these claims as nothing more than ad hominem attacks designed to discredit him and, by extension, his intelligence disclosures.[18]

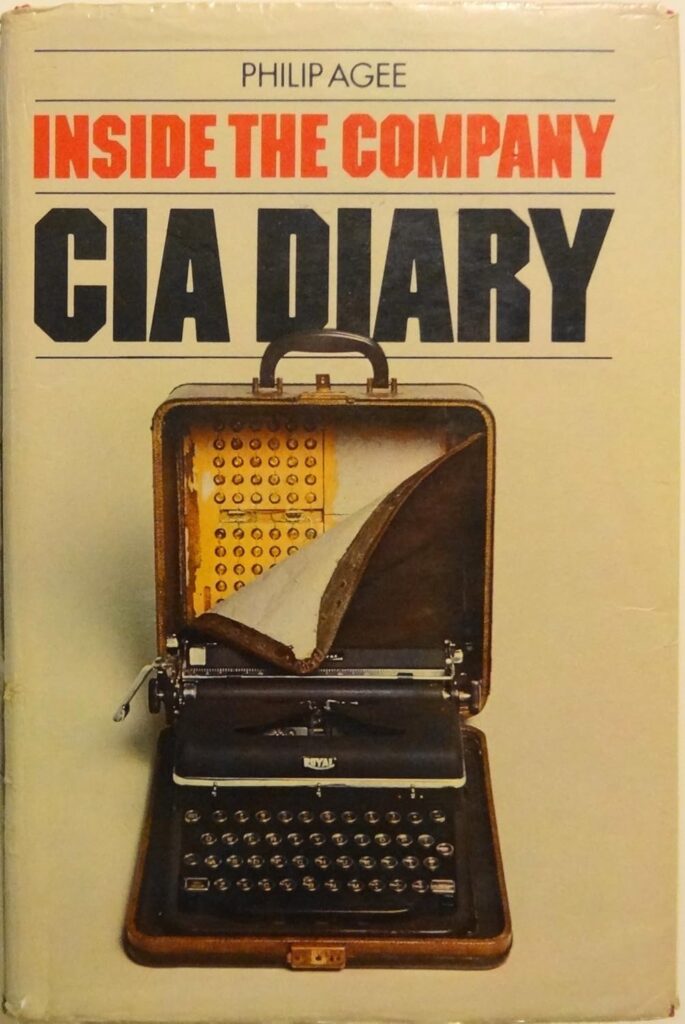

CIA stations were rife with toxic masculinity. In Inside the Company, Agee makes little mention of the station’s assistants, who were generally young women and, hence, tended to become invisible in the historical record. One exception was Barbara Svegle, a secretary-typist in the Quito station during the early 1960s who served as a courier to Aurelio Davila Cajas, one of the station’s Ecuadorian agents.[19]

But that was more an exception than the rule. Because they typed the outgoing cables and dispatches, read incoming traffic from headquarters, and maintained financial records, the dissident CIA officer John Stockwell described these assistants as part of a very small handful of people “who knows everything the CIA is doing.”[20] Seemingly no memoirs, studies, or extended discussions exist of their role in the agency’s operations.

Then there is the case of the CIA’s deputy chief of mission’s secretary Sharon V. Hurley. In his subsequent memoir On the Run, Agee recounts meeting Hurley in Germany in the 1970s after he left the agency. He had “hardly noticed” her in Quito, even though her “desk had been a minute’s walk down the hall” from his.[21, 22]

What is equally notable is what Agee does not mention in his memoir Inside the Company. Shortly before leaving in December 1963, Agee asked for permission to sell his 1959 Renault and import a Triumph TR4. Only a couple of weeks later, he had to turn around and sell the Triumph that had only recently arrived on the steamer Salinas.[23] But what is up with the purchase of a sporty new red car? Was his departure unexpected? Was this a sign of an early mid-life crisis?

An even odder omission in the memoir is any mention of Agee’s replacement in Ecuador. Shortly before he left, William F. Frederick arrived in Quito as the new assistant attaché in the political section of the embassy.[24] After naming hundreds of names—of case officers, agents, and others with connections to the CIA—why not mention the person who carried on his work? Again, the archives leave more questions than answers.

Instead, Agee closes the section of his memoir on Ecuador with reflections on how much the situation in the country had changed since his arrival three years earlier. He thought previous officers would no longer recognize the station because it had grown so much, with more still scheduled to arrive. The station’s budget had also grown substantially.

Although Agee never uses the term “controlled American source,” most of these officers were still under diplomatic cover, although Warren Dean, the chief of the Guayaquil base, had plans to expand operations with non-official cover.[25] Overall, though, the more things changed the more they stayed the same.

Letter from Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., to John F. Kennedy, “CIA Reorganization,” Washington, D.C., June 30, 1961, The President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection, 2025 Documents Release, https://www.archives.gov/files/research/jfk/releases/2025/0318/176-10030-10422.pdf; Peter Kornbluh and Arturo Jimenez-Bacardi, eds., “CIA Covert Ops: Kennedy Assassination Records Lift Veil of Secrecy,” Briefing Book #888, National Security Archive, March 19, 2025, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/2025-03-19/cia-covert-ops-kennedy-assassination-records-lift-veil-secrecy. ↑

United States Department of State, Foreign Service List (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, January 1961), 18; John D. Marks, “How to Spot a Spook,” Washington Monthly (November 1974), 5. ↑

The embassy identified Weatherwax as “employed in Ecuador under the Extension of the Cooperative Agreement with the Ministry of Economy dated April 14, 1955.” See Letter from Embassy of the United States to Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Quito, November 30, 1959, Oficio no. 229, B.18.80 (Notas recibidas de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, Tomo II, 1959), Archivo Histórico del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores (AHMRE), Quito, Ecuador. ↑

Letter from Embassy of the United States of America to Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Quito, June 4, 1962, Oficio no. 578, B.18.85 (Notas recibidas de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, Tomo I, 1962), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Earl H. Lubensky to All American Personnel, “Order of Precedence Among American Embassy Officers and Wives,” Quito, November 2, 1962, B.18.86 (Notas recibidas de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, Tomo II, 1962), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from John E. Karkashian to Spencer M. King, Washington, D.C., August 3, 1962, Record Group 84 (Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State), Ecuador; U.S. Embassy, Quito; Classified General Records, 1941-1963, Entry UD #2396, Box 85 [Old Box 2]: 1962-1963: 350 — 350, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, Maryland. ↑

Letter from Embassy of the United States of America to Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Quito, August 20, 1962, Oficio no. 141, B.18.86 (Notas recibidas de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, Tomo II, 1962), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Embassy of the United States of America to Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Quito, December 12, 1960, Oficio no. 232, B.18.82 (Notas comunes recibidas de la Embajada de los Estados Unidos de América en Quito, 1960, Tomo II), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Embassy of the United States of America to Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Quito, December 15, 1960, Oficio no. 237, B.18.82 (Notas comunes recibidas de la Embajada de los Estados Unidos de América en Quito, 1960, Tomo II), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Embassy of the United States of America, Quito, December 20, 1960, Oficio no. 381.1(22)/25-DP, N.17.2 (Notas comunes Notas enviadas a la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, 1959-1961), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Embassy of the United States of America to Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Quito, December 28, 1960, Oficio no. 243, B.18.82 (Notas comunes recibidas de la Embajada de los Estados Unidos de América en Quito, 1960, Tomo II), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Edward S. Little to José Ricardo Chiriboga Villagómez, Quito, February 17, 1961, Oficio no. 306, B.18.83 (Notas recibidas de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, Tomo I, 1961), AHMRE; Letter from Alvin T. Slemons to Benjamín Peralta Páez, Quito, January 24, 1963, Oficio no. 448, B.18.87 (Notas recibidas de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, Tomo I, 1963), AHMRE; Letter from Alvin T. Slemons to Benjamín Peralta Páez, Quito, April 24, 1963, Oficio no. 613, B.18.87 (Notas recibidas de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, Tomo I, 1963), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Edward S. Little to José Ricardo Chiriboga Villagómez, Quito, January 10, 1961, Oficio no. 253, B.18.83 (Notas recibidas de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, Tomo I, 1961), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Embassy of the United States of America, Quito, March 11, 1963, Oficio no. 30 DP, N.17.3 (Notas comunes enviadas a la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, 1962-1963), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Edward S. Little to José Ricardo Chiriboga Villagómez, Quito, February 28, 1961, Oficio no. 315, B.18.83 (Notas recibidas de la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, Tomo I, 1961), AHMRE. ↑

John Barron, KGB Today: The Hidden Hand (New York: Reader’s Digest Press, 1983), 228. ↑

“Points of Discussion,” undated, Box 5, Folder 9, Philip Agee Papers, Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives, New York University, New York. ↑

Philip Agee, On the Run (Secaucus, NJ: Lyle Stuart, 1987), 91. ↑

Philip Agee, Inside the Company: A CIA Diary (London: Penguin, 1975), 126. ↑

John Stockwell, In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1978), 136. ↑

Agee, On the Run, 250. ↑

Letter from Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Embassy of the United States of America, Quito, December 31, 1963, Oficio no. 118 DP, N.17.3 (Notas comunes enviadas a la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, 1962-1963), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Embassy of the United States of America, Quito, December 9, 1963, Oficio no. 162 DP, N.17.3 (Notas comunes enviadas a la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, 1962-1963), AHMRE. ↑

Letter from Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Embassy of the United States of America, Quito, December 2, 1963, Oficio no. 158 DP, N.17.3 (Notas comunes enviadas a la Embajada de Estados Unidos en Quito, 1962-1963), AHMRE. ↑

Agee, Inside the Company, 321. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Marc Becker is professor of Latin American history at Truman State University in Missouri.

He is author of The FBI in Latin America: The Ecuador Files (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017); and The CIA in Ecuador (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021) among other works.

Marc can be reached at marc@yachana.org.