The assassin was in the pay of a police general trained by the CIA who functioned as the hatchet man of another CIA asset.

[This article continues CAM’s commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. Additionally, it follows CovertAction Magazine’s investigation into historic CIA crimes and into the CIA’s role in political assassinations—Editors.]

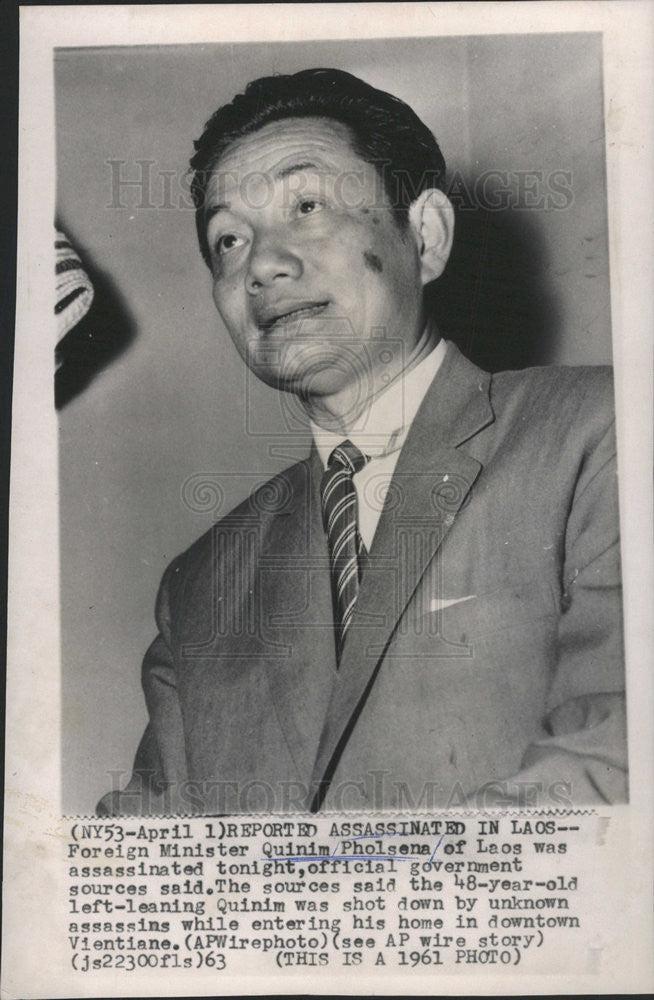

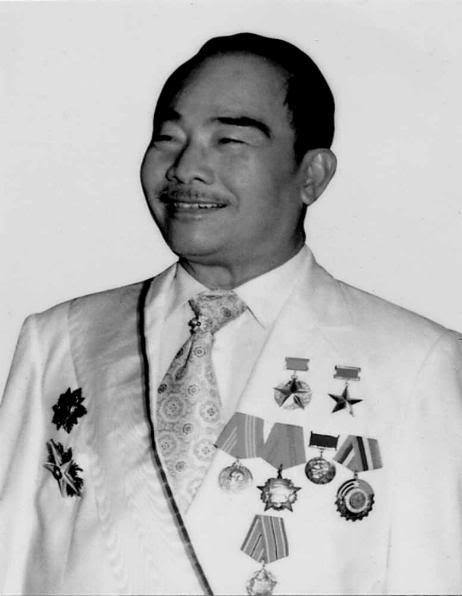

On April 1, 1963, Quinim Pholsena, Laos’s Foreign Minister and head of the “Peace and Neutrality” party, was shot and killed as he walked up the steps of his Vientiane villa after attending a Royal reception.

A man of Chinese descent, Quinim had risen in the Laotian civil service in the 1950s and was intent on strengthening the ties between Laos’ then-neutralist government and the left-wing Pathet Lao.

Time Magazine wrote of him: “unlike most other Laotian politicians, he did not belong to a rich or princely family. He made a lot of money as a merchant and investor, but in politics he was always a man of the left; though officially a member of Souvanna Phouma’s neutralist party, his line was usually indistinguishable from that of the Communist Pathet Lao.”

Quinim’s killer, Lance Corporal Chy Kong, 20, was one of his body guards assigned to protect him. The CIA claimed that he was working for an ambitious General named Kong Le, who had mounted a previous coup attempt and was then forging a liaison against the Pathet Lao with General Phoumi Nosavan, a favorite of the Pentagon and CIA.[1]

Quinim’s wife, Phayboun, a political figure in her own right, was severely wounded in the assassination. She was left to bleed on the steps alongside her husband’s body and taken to the hospital only five hours later, after she had been taken inside the villa by a servant.

Those who tried to enter the villa were stopped by bodyguards at gunpoint. Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma and the Pathet Lao Minister of Information, Phoumi Vongvichit, were among those trying to get in and insisting that Ms. Pholsena be taken to a hospital.

According to Time magazine, “when word of the murder reached the King’s residence on the banks of the Mekong, it failed to dampen the merrymaking at the Royal reception Quinim had attended before he was shot. The band played on, the ministers and their ladies continued to sip champagne. Shrugged one guest: ‘No one had it more coming to him and from more quarters than did Quinim Pholsena.’”

After shooting Quinim and his wife, Chy made no attempt to flee. In a signed confession, he claimed that Quinim, 48, was trying to overthrow the government and bribe neutralist officers to defect to Pathet Lao forces encamped in the northern Plain of Jars, where fighting had recently broken out.[2]

Chy was taken to live with a high-ranking neutralist cabinet member and, 12 days later, was nominally arrested and put in a prison controlled by the forces of Phoumi Nosavan, a right-wing general who had been empowered by the White House, Pentagon and CIA.[3]

Ms. Pholsena, while recovering from major leg wounds, told Australian journalist Wilfred G. Burchett that there was “no doubt that Nosavan and the CIA had arranged the assassination.”[4]

Prior to her husband’s death, Ms. Pholesena said that Quinim had told her that on a visit to the U.S. with Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma, highly placed agents made vigorous attempts to buy him over and made all sorts of veiled threats when he scornfully rejected their offers.[5]

Souvanna had association with the CIA; CIA officer R. Campbell James had developed a relationship with him in the 1950s.[6]

Quinim had witnessed Souvanna assuring President John F. Kennedy that most Laotians preferred the U.S. to the Pathet Lao and agreeing to Kennedy’s demand that, at all costs, no U.S. military or economic aid should pass into Pathet Lao hands.

Souvanna allegedly told Kennedy that he would do everything possible to “hunt, weaken and eventually eliminate Pathet Lao influence.”[7]

This pledge ran counter to a series of agreements establishing a coalition government, headed by Souvanna, that was supposed to integrate the Pathet Lao and Laotian military. Pathet Lao leader Prince Souphanouvong was to become Deputy Prime Minister with the portfolios of economy and planning, and General Phoumi, Deputy Foreign Minister and Minister of Finance.

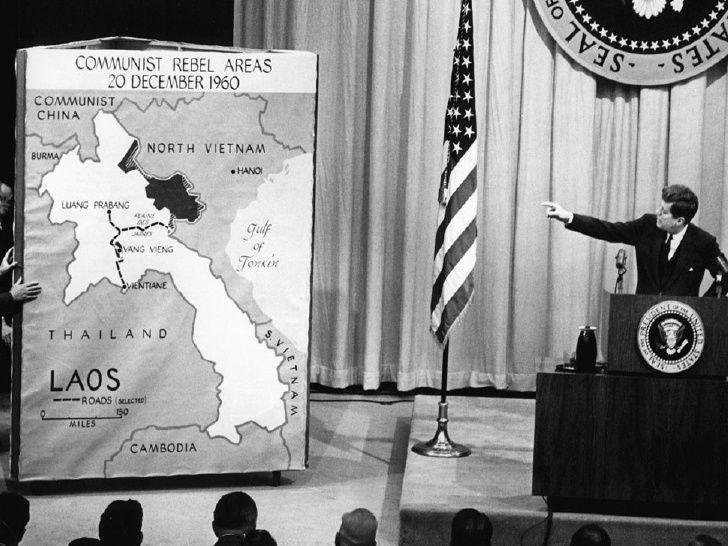

Laos had been transformed into a CIA playground in the 1950s following the signing of the 1954 Geneva agreements granting the Kingdom of Laos independence from France.

The Pathet Lao were poised to take power because they had led the liberation struggle against France in conjunction with the Vietminh (Vietnamese communists), and promoted land reform, literacy, health care and other programs advocated by the Maoists in China.

Even the State Department characterized Prince Souphanouvong as an “outstandingly able and energetic leader.” America’s allies, by contrast, Newsweek reported, represented “the traditional ruling class and had little interest in reform. The political methods they used—stuffing ballot boxes and intimidating neutralist voters⎯succeeded only in driving the moderates to the left.”[8]

To prevent the Pathet Lao takeover, the Eisenhower administration supported anti-communist factions in Laos and spearheaded a military coup in 1960 headed by General Phoumi after the Pathet Lao won elections. The Pathet Lao were thrust underground and, after Souphanouvong escaped from prison on the eve of his scheduled execution, began fighting the Royal Lao Army (RLA), which was entirely financed by the U.S.

The Kennedy administration’s plan was to back the formation of a coalition government while facilitating Souvanna’s alliance with Phoumi and the right-wing generals.[9]

W. Averell Harriman, who headed the U.S. delegation at the 1962 Geneva Conference, stated: “We must be sure the break comes between the Communists and the neutralists, rather than having the two of them teamed up as they were before.”[10]

Quinim Pholsena was a roadblock to this strategy and so had to be killed.

The U.S. State Department regarded Quinim as “a threat to the U.S…probably the most dangerous individual in Souvanna’s Cabinet.”[11]

Besides his affinity for the Pathet Lao, he objected to Air America flights supplying the CIA’s clandestine Hmong army, which had been created to fight the Pathet Lao. (the Hmong were a persecuted minority whose Ly clan previously allied with the French).[12]

According to Burchett, Quinim’s murder “was the signal for an armed coup, the first stage of which was to be the seizure of the strategic Plain of Jars.”[13]

Burchett found out that Quinim’s killing was arranged by General Siho Lamphouthacoul, an extreme right winger, according to The New York Times, who had been trained under USAID police training programs. He headed an assassination program under General Phoumi designed to eliminate the higher cadres of the Pathet Lao and progressive neutralists like Quinim.[14]

The USAID police training programs in Laos provided a cover for CIA clandestine operations.

General Siho was a CIA “asset” who had played a vital role in rigging the 1960 election on General Phoumi’s behalf.

A stocky man of mixed Chinese-Laotian parentage and humble background, Siho had attended the General Staff School in Taiwan, where he fell under the influence of General Chiang Ching-kuo, chief of Taiwan’s secret police and eldest son of dictator Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi), who had close ties to American intelligence.

Described by The New York Times as “rough and tenacious,” and by his CIA case officer as “vain” and “dangerous” [like Phoumi] if in a flash of hot temper,” Siho was known for use of “gangster methods to eliminate the opposition,” including, according to U.S. reports, “the use of twisted cord in interrogating recalcitrant subjects.” [15]

A 1965 USAID Office of Public Safety (OPS-police training agency) report authored by Frank Walton, Paul Skuse and Wendell Motter specified that General Siho and Phoumi had used the Laotian police as a “private army” and raised money through “considerable traffic and smuggling into Thailand” as a means of “raising money for a wave of repression against political opponents,” including “mass jailings and executions.”

Siho’s men, according to the report, engaged in “Gestapo-like tactics, carrying out operations that “rivaled anything ever heard of in terms of brutal, corrupt activity.”[16]

These comments provide a stunning rebuke to the corrupting effects of U.S. foreign policy in Laos and its empowerment of a clique of criminal gangsters with Nazi-like proclivities.

With Quinim Pholsena removed from the scene, the Kennedy and subsequently Johnson administrations were able to pursue their doomed strategy of trying to crush the Pathet Lao.

Since the RLA was hopelessly incompetent and corrupt, an ace in the hole was the CIA’s clandestine Hmong army, whose prowess CIA Director William Colby bragged about in the PBS Television history of the Vietnam War.

Following a classic colonial strategy, the CIA’s recruitment of the Hmong allowed the U.S. to ignore the provisions of the 1962 Geneva Accords that called for the removal of foreign troops from Laos as the Hmong could be negotiated with independently as a tribal entity.[17]

A July 1963 memo to President Kennedy by interim National Security Adviser Robert W. Komer states that Kennedy had authorized military assistance to irregular (Meo—euphemism for Hmong) forces trained by the CIA, operating under the cover of USAID, and that efforts had been taken to “strengthen” these “irregular” and “tribal” forces.[18]

Kennedy advisers like Roger “Tex” Hilsman had experience training tribal groups in Burma during World War II and, according to an official CIA history, “entertained fantasies from their OSS days of rousing the tribal population to overthrow a communist regime. They wanted to defeat the guerrillas at their own game.”[19]

Hilsman’s fantasy was never fulfilled because the Pathet Lao guerrillas gained the upper hand by adopting Maoist strategies and took over Laos’s government in 1975.

In the interim 12 years, tens of thousands of Laotians were killed and much of northern Laos was turned into a wasteland as a result of massive CIA bombing operations on the Plain of Jars and along the Ho Chi Minh trail bordering North Vietnam.

The Hmong were decimated and forced to recruit child soldiers for a “one-way helicopter ride to death,” as journalist T.D. Allman characterized it. CIA officer Edgar “Pop” Buell told correspondent Robert Shaplen: “Here were these little kids in their camouflage uniforms…[who] looked real neat…But V.P. [Vang Pao] and I knew better. They were too young and they weren’t trained and in a few weeks 90 percent of them will be killed.”

Vang Pao was the Hmong chief who was recruited by the CIA to head its clandestine army.

In 1963, he was busted for drug smuggling by Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) officer Bowman Taylor, who was subsequently thrown out of Laos. FBN Commissioner Henry Giordano was told by the CIA that the arrest “never happened,” and the CIA gave back to Vang Pao his Mercedes-Benz and 50 kilos of morphine base, according to historian Douglas Valentine.[20]

CIA operative Anthony Poshepny told Valentine that Vang Pao “made millions dealing drugs,” and “enjoyed the high life at his villa in Vientiane, where he made illicit deals under the gaze of CIA officers. The CIA even gave him his own D-3 with a crew of KMT [Chinese Guomindang] mercenaries that flew narcotics to cash customers around Southeast Asia.”

The Hmong’s main cash crop was opium, which was used to finance the secret war. This is all part of a hidden history barely known to the American public as Laos was a mere sideshow to the Vietnam War, receiving little publicity at the time.

A State Department official commented: “This is [the] end of nowhere. We can do anything we want here because Washington doesn’t seem to know that it exists.”[21]

Anything we want included political assassination of neturalist political figures like Quinim Pholsena trying to bring peace to Laos and to establish a coalition government that functioned in the interests of the country’s people.[22]

William J. Rust, So Much to Lose: John F. Kennedy and American policy in Laos (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2014), 196; http://www.faqs.org/cia/docs/84/0000598464/ASSASSINATION-OF-QUINIM-PHOLSENA.html. ↑

Chy also said he had acted in retaliation for the assassination of rightist Colonel Ketsana. ↑

For accounts of the assassination, see “After the Party,” Time, April 12, 1963; Wilfred G. Burchett, The Second Indochina War: Cambodia and Laos (New York: International Publishers, 1970), 155. Images from Quinim’s funeral can be found here. ↑

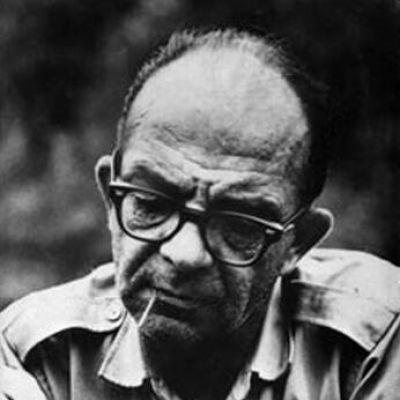

Burchett, The Second Indochina War, 155. The first Western journalist to break through the censorship at Hiroshima after the dropping of the atomic bomb, Burchett covered the Indochina War from the perspective of the Indochinese people. He had been one of the few Western journalists to cover the Korean War from the point of view of the North Koreans and Chinese. ↑

Burchett, The Second Indochina War, 155. ↑

Rust, So Much to Lose, 136. A wealthy Yale graduate who spoke with a posh English accent and carried a cane filled with brandy, James mixed well with the older Lao elites, according to historian William J. Rust. ↑

Burchett, The Second Indochina War, 155. ↑

Causes, Origins, and Lessons of the Vietnam War: Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, 92nd Cong., 2nd sess., May 9, 10, 1972 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1972), 198; Bernard B. Fall, “The Pathet Lao: A ‘Liberation’ Party” in The Communist Revolution in Asia: Tactics, Goals, and Achievements, Robert A. Scalapino, Ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1965), 180-82.

Jeremy Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression: Police Training and Nation-Building in the American Century (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), 132. ↑

Quoted in Burchett, The Second Indochina War, 152. Considered by some historians as a key architect of U.S. Cold War policy, Harriman was the son of railroad tycoon E.H. Harriman who helped found the famous Wall Street firm, Brown, Brothers Harriman. He served as Governor of New York and was later mentor to Joe Biden in the U.S. Senate. Historian William J. Rust wrote that “what Kennedy wanted carried out in Laos…was the establishment of a Souvanna-led coalition government with sufficient right-wing political and military strength to resist a communist takeover and preserve Laotian neutrality.” Rust, So Much to Lose, 86. ↑

Rust, So Much to Lose, 132, 194. ↑

Rust, So Much to Lose, 194. Souvanna Phouma sanctioned these flights. ↑

Burchett, The Second Indochina War, 152. ↑

Burchett, The Second Indochina War, 156; Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression, ch. 6. Burchett wrote that the murder of Pholsena, the head of the “peace and neutrality policy” comprising progressive forces among the neutralists, was the signal for an armed coup, the first stage of which was to be the seizure of the strategic Plain of Jars. The U.S. Fleet at the time moved into the Gulf of Siam. ↑

Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression, 131. ↑

Idem. ↑

Ibid., 132, 133. ↑

Robert W. Komer, Memo to the President, July 29, 1963, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, Boston, Massachusetts, Laos records, https://www.jfklibrary.org/sites/default/files/styles/orange_dam/https/static.jfklibrary.org/7611anvfmox8svdu46t464h7q658q80i.jpg?itok=cZaIfVH6 ↑

Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression, 135. ↑

See Douglas Valentine, Pisces Moon: The Dark Arts of Empire (Walterville, OR: TrineDay, 2023); Douglas Valentine, The Strength of the Wolf: The Secret History of America’s War on Drugs (London: Verso, 2006). ↑

Len E. Ackland, “No Place for Neutralism: The Eisenhower Administration and Laos,” in Nina S. Adams and Alfred W. McCoy, Eds., Laos: War and Revolution (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), 139-40; Charles A. Stevenson, The End of Nowhere: American Policy Toward Laos Since 1954 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1972), 1, 29. ↑

- As a sidenote to this story, Quinim’s daughter, Khemmani Pholsena is now a top aide to the president of Laos, Thongloun Sisoulith. Her promotion was a sign the government intended to leverage its connection with China. Chinese Premier Xi Jinping went to the Beijing Bayi School in the early 1960s with Quinim Pholsena’s son, Sommao Pholsena, who became the Vice General Manager of Laos’s State Utility. A member of the Laos National Assembly and former transport minister, he signed on to Laos’s participation in the Belt and Road Initiative, a massive infrastructural development project initiated by China.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.