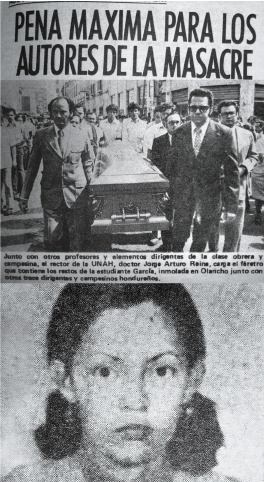

June 25 marked the 50th anniversary of the Los Horcones massacre, a gruesome and desperate event that still haunts Honduran society and is emblematic of major forces that have shaped much of modern global history.

A thorough and well-sourced description of the Los Horcones massacre and its context is provided in Penny Lernoux’s now-classic, Cry of the People: United States Involvement in the Rise of Fascism, Torture and Murder and the Persecution of the Catholic Church in Latin America [(New York: Doubleday, 1980), 109-114]. Her account is disturbing but worth reading, if only to help us understand the savagery that resides in the plans of those who must dominate and control at all costs, and the events we see today in Honduras and elsewhere. Here, I can only briefly outline what happened.

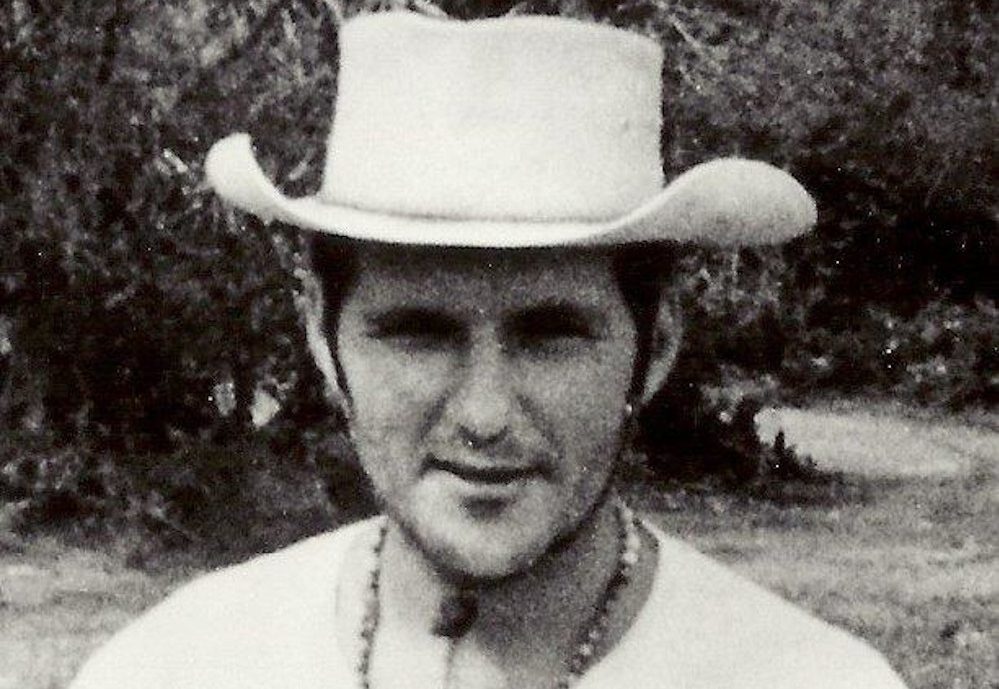

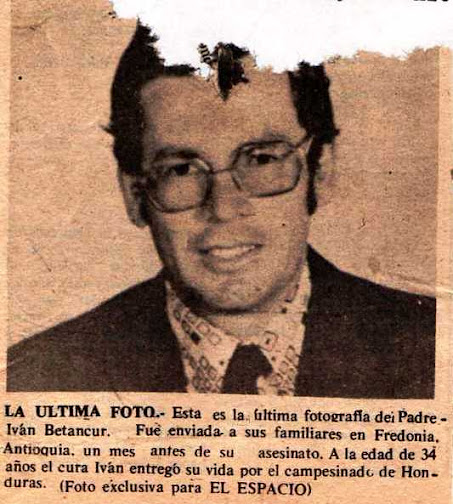

The massacre occurred in the Lepaguare Valley, in the municipal district of Juticalpa, in the Department of Olancho, on the hacienda “Los Horcones,” There, a group of military officers and landowners (or their paid agents) tortured and murdered 15 people, including 11 peasant farmers, two young women, and two Catholic priests—Ivan Betancur (a Colombian citizen) and Casimir Cypher (a U.S. citizen from Wisconsin).

The priests were singled out for the worst torture and their bodies were mutilated while they were still alive. The peasant farmers were burned to death in a bread oven. The perpetrators threw the bodies in a well on the Los Horcones property and dynamited the well. There was at least one witness hidden in the woods at a distance.

The peasants were leaders and members of the National Peasant Union (Union Nacional de Campesinos, UNC), an organization influenced by the social teachings of the Catholic Church that emphasized social justice, human rights, and a ”preferential option for the poor.” The UNC had organized a “March of Hunger,” to highlight their demands for land that they felt was illegally and unjustly being monopolized by the large ranchers. The large landowners in the region decided to eliminate this threat, and the Honduran military government colluded with them in doing so.

The military blocked the march, but that was only the catalyst for a vicious campaign against the peasants and their Catholic Church supporters. The landowners set a price of $10,000 for the head (literally) of the progressive Catholic Bishop of Juticalpa, Nicholas D’Antonio (a U.S. citizen from New York). They also paid the military commander of the region $2,500 to kill Father Betancourt whom they saw as a supporter and enabler of the peasants. (In current dollars, those sums would be considerably higher.)

It soon became clear that the Honduran military government under General Juan Alberto Melgar Castro was deeply involved. The government responded to the Los Horcones massacre by giving a few military officers jail sentences, but it also raided and destroyed the offices of the UNC, hunted other UNC leaders, and effectively ordered the expulsion from Honduras of all foreign priests.

Bishop D’Antonio was out of the country during the massacre. Had he been in Honduras he would almost certainly have been killed and beheaded. He could not return to Honduras and was forced to close the diocese.

As Lernoux documents, the campaign against peasant organizations and progressive elements of the Catholic Church had been going on for months before Los Horcones, with arrests, beatings and imprisonment of priests and peasants in different parts of Honduras.

In 2013, Honduran Jesuit priest and human rights leader Ismael Moreno (Padre Melo) wrote that the Los Horcones massacre was probably the starkest example of government repression against the Catholic Church in recent Honduran history, and that it caused Church leaders and many others to move away from their support of popular demands for social justice. But its significance goes beyond even that.

I first visited Honduras in 1974, one year before the Los Horcones massacre. What I saw was a very different scene. One afternoon, the Jesuits with whom I was staying took me to a ranch where a group of peasant farmers was busy preparing a plot of land for cultivation. The ranch belonged to a beef and hamburger fast food corporation in the U.S. The peasants were occupying without permission a small portion of the huge ranch.

Such land occupations (tomas de tierra) were and still are a regular event in Honduras where rural communities desperately need land to plant food crops, while large corporations and landowners hold thousands of acres of unused land. A contingent of Honduran soldiers was loitering in the road beside the plot where the peasants were working. The soldiers did nothing to stop them, but they did prevent the corporation’s security guards from forcibly evicting the peasants.

I was aware that this was a very rare scene in Honduran history. The military government, in a very brief liberal moment under General Oswaldo López Arellano, had passed the Agrarian Reform Law of 1974 that embodied the principle (in theory) that all Hondurans had the right to a piece of land. Peasant groups took that seriously as they occupied unused lands. “We are the agrarian reform,” they sometimes said. The contrast between this and the events of 1975 could not have been more stark.

Much of recent Honduran history has been marked by such contrasts. The government of President Carlos Roberto Reina (1994-98) managed to exercise some civilian control over the military and to sign international agreements for the rights of the country’s Indigenous people, only to have these advances ignored in practice and undone in the following decade.

Manuel Zelaya, who became Honduran president in 2006, was the son of the owner of Los Horcones. Given his family background, the Honduran landowning elite and the U.S. government expected President Zalaya to remain faithful to the interests of his landowning social class.

When he declared a moratorium on large mining projects and began to consult peasant groups about their needs and concerns, the elite regarded him as a class traitor. He was forcibly deposed and sent into exile on June 28, 2009.

There followed 12 years of right-wing repression and corruption, mostly under President Juan Orlando Hernández, one of the organizers of the 2009 coup. Those years were marked by the increasing power of foreign corporations, drug lords and criminal gangs, and the killing, criminalization and displacement of peasant communities and environmental defenders and their organizations. People began to refer to the country as a narco-dictatorship.

The United States was, to say the least, not unhappy about the 2009 coup, and continued to support Hernández until it became clear that his unpopularity and the rising level of anger among the Honduran population was likely to lose him the 2021 election.

I was in Honduras for that election. Hernández’s National Party operatives tried to bribe peasants by offering them money and other desirable goods if they promised to vote for him. Some later said they accepted the bribe but did not vote for him. Hernández’s hand-picked successor was defeated. (Powerful rulers who underestimate the “simple” rural people are often shocked by the result. Somoza made a similar mistake in Nicaragua in the 1970s.)

Thus, in yet another apparent contrast, Hernández’s party lost to Xiomara Castro, who promised a major reform and an end to corruption. When Hernández lost, the U.S. demanded his extradition to stand trial in New York for drug trafficking. He was convicted, sentenced to 45 years in prison, and remains in a U.S. prison. From staunch ally of the U.S. to convicted criminal, he seems to be yet another “victim” of U.S. imperial expediency.

During these past four years, Xiomara Castro’s government has been a classic example of the difficulties facing reformist efforts in a country largely controlled by a determined and ruthless elite that has the support of the U.S. and powerful U.S. corporate interests. In a previous article (CAM, May 3, 2023), I wrote about the dilemmas facing her government. Beyond these dilemmas, Castro has endured veiled and public warnings from the U.S. Embassy that her reforms might be her undoing.

As president, Xiomara Castro and her government have managed to make some meaningful changes, but change is difficult in the face of a deeply entrenched network of repression and corruption. Disillusionment and frustration among Hondurans at the failure of more sweeping change is something the Honduran elite and its Washington allies want to channel to undermine her government. They would prefer to have her term become simply another short period of attempted liberalization rather than the start of an ongoing tide of change in Honduran history.

This 50th anniversary year of Los Horcones also happens to be an election year in Honduras. National and local elections are scheduled for November. It is certain that the United States will, as always, be deeply involved in shaping the outcome. Whoever wins the election in November, significant change is unlikely, or it will be slow and costly in coming unless, perhaps, the United States as the major influence in Honduras supports significant change—something that would require change in the U.S. itself.

In a global context, Los Horcones at 50 years is part of a much larger conflict that has deeply shaped the past century, especially in Latin America and parts of Asia and Africa. Anthropologists, rural sociologists, and political economists have written about it. In the 1970s, Sidney Mintz wrote about what he and others called the proletarianization of peasant communities in the colonial Caribbean.

At the same time, Rodolfo Stavenhagen (1970), Ernest Feder (1971) and others were documenting and critiquing the massive displacement of rural communities by corporate extractive industries in Latin America, and the millions of displaced small farmers who roamed the continent looking for work—a cheap labor force and a growing urban population of desperately poor people. More recently, Mexican anthropologist Sergio Quesada-Aldana and others have used the term descampesinizar (to de-peasantize) to refer to the elimination of rural communities and peasants from the land.

This elimination takes place in several ways: making people landless, criminalizing their way of life, killing them, undermining their cultural values. Making people landless is accomplished by legal and illegal machinations; by making environmental conditions so bad that communities cannot survive and must move or scatter; or by killing community leaders so as to frighten others. Local elites and foreign corporations enlist the muscle of national governments and their security forces in these thefts.

The global corporate economy uses the land for its own profit while harnessing landless people as a cheap labor pool. Two centuries ago, half the world’s population were rural small farmers, peasants. They were the food suppliers and the foot soldiers (often under duress) of empires.

Today, their numbers are a fraction of what they were. Their land-rooted way of life is considered obsolete in the global commercial economy. Empire today depends on direct control of land and resources and a large, landless and cheap labor pool.

Now and in the near future, even this labor force of recycled peasants is quite likely to become a victim of mechanization and advanced technology, making them entirely superfluous in the plans of global capital—not needed as workers and too poor to be consumers. We already see the result of that in cities filled with displaced peasant families whose children grow up in poverty, vulnerable to gang recruiters and to other threats to body and soul. The cost, in endless conflict and misery, is incalculable.

Around 2015, landowners in another part of Honduras offered a $50,000 reward to anyone who would kill the local Catholic pastor, a Jesuit priest from the U.S. whom I knew. His support for the peasant communities’ demands made him an enemy of the landowners as they systematically seized land and murdered local peasant leaders. That was one of many similar situations. [NOTE: These four lines look like there is more space between each line than normal.]

It does not have to be this way. There are examples of thriving peasant communities that maintain their way of life, their identity, and their ability to make important decisions while contributing to the food security and economy of their country. Many studies have shown that peasant farmers and cooperatives are often more productive than large plantations. What is required is a government that believes in the worth of peasant communities and is willing to support them while curbing the worst predations of large landowners and corporations. This shift in a country’s political economy and mentality is seldom easy and never perfect.

Los Horcones happened and continues to happen in Honduras and in many other places, in ways large and small so that global capital can have the world at its disposal, unencumbered by self-reliant communities of small farmers on the land.

Los Horcones is emblematic of the insatiable forces that drive this situation. That is why we must remember horrific events like Los Horcones today. The courage and sacrifice of the peasants and their supporters reminds us of what is at stake.

[Note: In descriptions of the Los Horcones massacre, the three foreign priests are named and, thanks to Lernoux, we know the names of the two young women—Maria Elena Bolivar who would have become Fr. Betancur’s future sister-in-law, and Ruth Garcia, a Honduran university student. I have not found anywhere the names of the eleven peasant members of UNC. There might be a story in that. If anyone knows their names, please share them. They deserve to be remembered by name. JP]

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

James Phillips is a cultural and political anthropologist with forty years as a student of Central America.

His major concerns are movements of social change, political conflict, human rights, colonialism, and immigrant and refugee populations.

He is the author of articles and book chapters on Honduras and Nicaragua. His most recent book is Extracting Honduras: Resource Exploitation, Displacement, and Forced Migration (Lexington Books, 2022).

James can be reached at anthrodocjp@gmail.com.