The following story has been told and retold all over the world, except in Portugal, where it actually happened. One day, I was informed by a very helpful little bird named Hastings that, in April 1943, a group of men from the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) sneaked into the Japanese Embassy in Lisbon, without the knowledge of the American government itself, with the intention of taking possession of the Japanese cipher book.

As if the story were not already elaborate enough, it is worth adding that today, 81 years later, it is still not known for sure whether it is even true. Or rather, it is common knowledge—at least among those who dedicate themselves to these matters—that the OSS was, in fact, involved in the theft of documents that were previously in the possession of the Japanese. However, it remains to be determined how the operation was conducted, what types of information (if any) were possibly extracted and, finally, what consequences arose from it.

Old soldiers never die

In April 1943, the world was in flames. Obviously, no major political or military actor, whether American or European, was in the least interested in the consequences that could arise from this incredible episode. After all, they had other things to worry about. In order to provide our readers with some context, we have taken the liberty of listing at least three major historical events that, at the time, were certainly of greater concern to the greatest and most important political decision-makers:

- Katyn massacre (public disclosure on April 13, 1943) : The discovery of the mass graves at Katyn exposed the murders of thousands of Polish officers at the hands of the NKVD in 1940, debunking Soviet propaganda and exposing the brutality of Stalin’s regime;

- Operation Vengeance (April 18, 1943): The death of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the architect of the attack on Pearl Harbor, had a direct strategic impact on the Pacific War, weakening the Japanese command and boosting Allied morale;

- Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (April 19, 1943): A symbol of human resistance, forever etched in the collective memory of the struggle against National Socialist oppression. The rebels held out almost as long (a difference of two weeks) as the entire French army during the Nazi invasion.

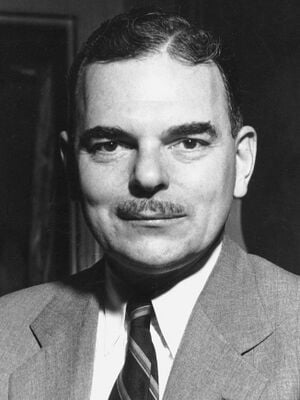

That said, it becomes clear why no one paid attention to what Donovan’s men were doing. It was only a year later, during the 1944 presidential elections, that the “Lisbon Affair” gained more relevance. On one side was Franklin D. Roosevelt, then president in office; on the other was Thomas E. Dewey, a young and somewhat ambitious man for whom the post of governor of New York State was clearly not enough.

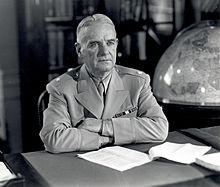

As we shall see later, behind the speeches and rallies, a shadow hung over the campaign: a secret so important that it could actually change the course of the war and, ultimately, of history. At least, that was what General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, believed. Today, we know with some degree of certainty that his concern was largely unfounded, since, according to some sources, the American intelligence services never stopped receiving privileged information about the Japanese method of action. But we will return to that later.

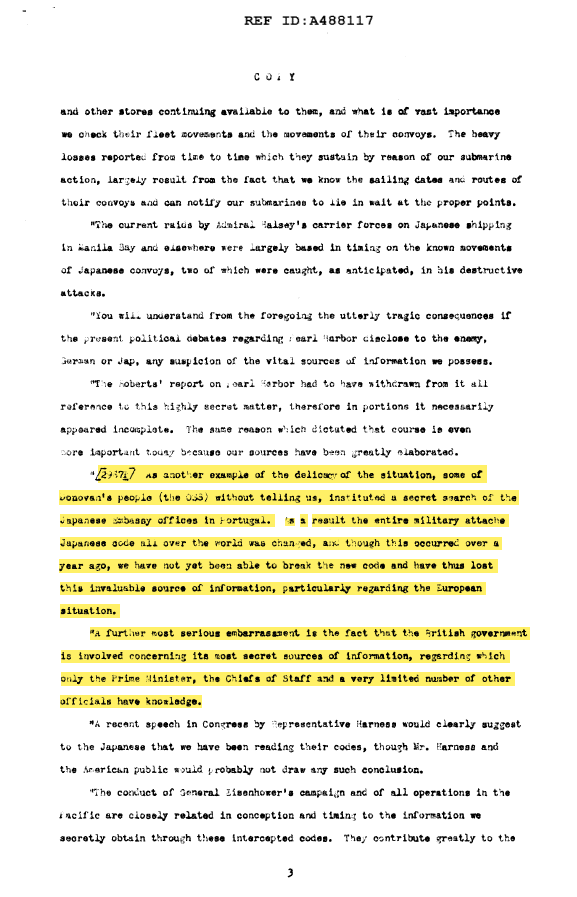

As a military man, General Marshall was considered a serious man, someone who would hardly compromise his principles. However, that same year, he committed an unprecedented act. In a desperate move—which, frankly, bordered on the unconstitutional—he ordered an emissary to deliver a letter to Dewey. The messenger was Colonel Carter Clarke, whom we will discuss later.

The message could not have been clearer: It was imperative that Dewey never mention, under any circumstances, that the United States and England had decrypted Japanese communications before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Why? The answer is simple: If such information were to reach the Japanese, they would certainly take the necessary measures to ensure that it would not happen again, depriving the Allies of a crucial war-time advantage.

There was, however, another, more sordid and calculating reason for not mentioning the matter. If Dewey had revealed that the United States had been aware of Japanese plans before Pearl Harbor, it could have significantly shaken the public’s confidence in Roosevelt, who was at the time accused by some sectors of the political class of having “allowed” the attack that led the country to enter the war.

Pure tactics. As is the case today, the power of public opinion continues to exert a great influence on political decision-making, even if it is often not realized. The letter was, after all, a dramatic appeal to Dewey’s patriotism. “If we talk about this,” it seemed to say, “the war may be prolonged, and more lives will be lost.” Pressed more than once, Dewey agreed to remain silent.

But, as they say, lies have short legs. The secret finally came to light shortly after the end of the war, when magazines such as Time and Life showed interest in publishing it, finally sharing with civil society the controversial details surrounding Clarke’s mission and Marshall’s letter.

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of people were utterly shocked by the revelation that their country—the one they had been taught from an early age to love and defend, under the illusion that it had their best interests at heart—had been aware of the Japanese plans long before the disastrous attack on Pearl Harbor. The messages showed beyond a shadow of a doubt that the Empire of the Rising Sun was planning an attack, though they did not specify where or when.

The question that echoed for years and shook the confidence of American society in its representatives was: Did Roosevelt know? Did he allow Pearl Harbor to happen in order to push the country into war? The very idea that the greatest figure in the nation would be willing to sacrifice his countrymen to serve a purpose with which the vast majority of the population did not agree haunted the minds of those who extolled a patriotism based on quicksand.

With the end of the war and in the face of the inferences of the media and civil society, Congress had no choice but to open a new, more detailed, investigation in 1945 into the details behind the attack on Pearl Harbor. The conclusion was reached, unsurprisingly, that the blame lay solely with Japan, exonerating all political officials in office at the time. This simplistic reasoning forced Senators Owen Brewster (R-ME) and Homer Ferguson (R-MI) to reject the majority’s conclusions and claim that it was “clear that the record was far from complete.”

Although the 646-page investigation was patently vague and redundant, it paved the way for the passage of the National Security Act of 1947, the creation of the CIA, and the founding of the current Department of Defense. Whether these outcomes, particularly the creation of the CIA, were positive or not is a discussion for another day.

You shall not slander!

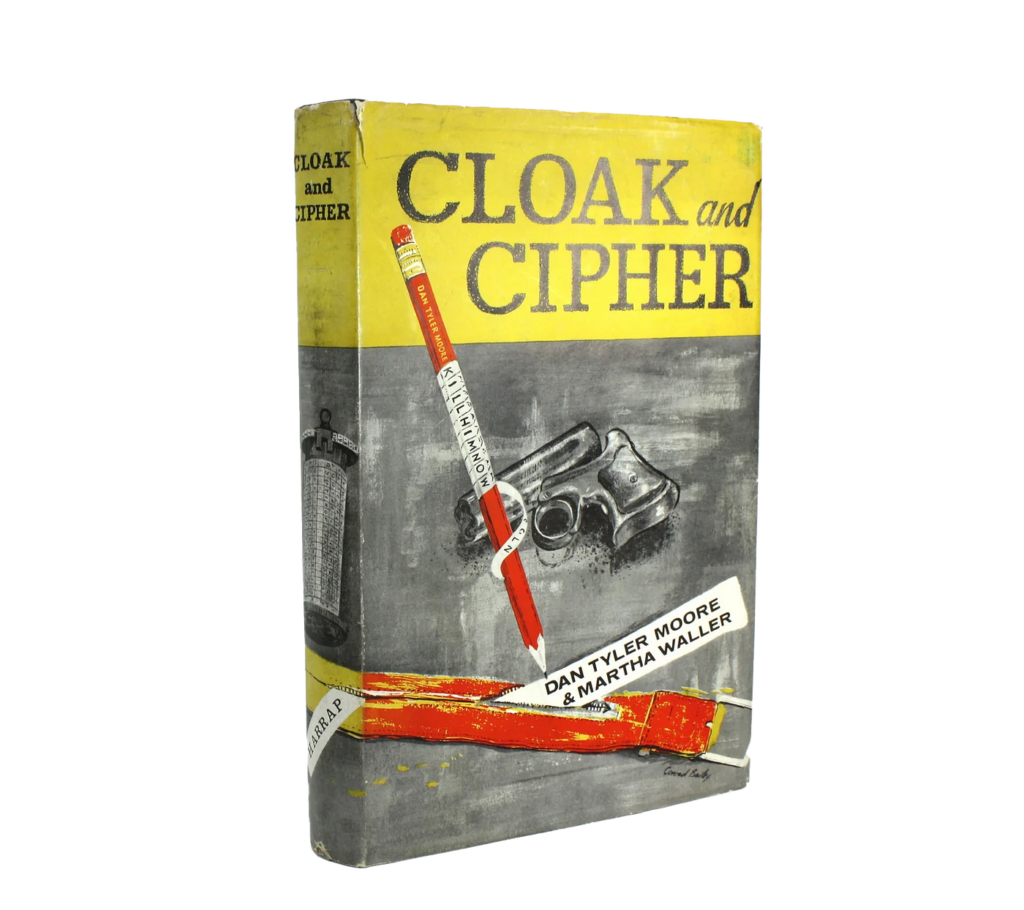

Now that we have explored the origins and how the public became aware of the controversy surrounding the Lisbon Affair, it remains for us to clarify whether the events unfolded exactly as General Marshall described them or whether his narrative deviates from the truth. As we will see, this version of events took root in the collective imagination, becoming a true legend. And, in fact, it generated intense debate, inspiring numerous publications. One of the first—if not the first—to address the scandal was the 1962 book Cloak and Cipher, by Dan Moore and Martha Waller. This work laid the foundations for a controversy that lasted for decades.

Ten years later, in 1972, former CIA employee R. Harris Smith published the book OSS: The Secret History of America’s First Central Intelligence Agency. That work, which caused some controversy, was based in part on contacts Smith made during his brief tenure at the agency.

However, as is usual with such sensitive subjects, not everyone was impressed. That same year, Cornelius Ryan, a journalist and writer specializing in military history, published a devastating review in The New York Times.

Starting from what was too rigid a premise, Ryan accused Smith of filling the book with inaccuracies and distortions resulting from a lack of official sources and an over-reliance on dubious espionage literature written by former OSS agents. Now, if he was denied access, how else could he have proceeded?

Ryan wrote in his review, published on September 17, 1972, that “Mr. Smith has clearly violated the first law of reporting: believe nothing unless it can be corroborated by other sources and confirmed by definitive records.”

In a blunt, even provocative way, Ryan argued that many of the oral histories he had collected came from veterans who had romanticized and exaggerated their experiences over the years. He suggested that many of these narratives were given a dramatic twist at the annual OSS veterans’ dinners, and that Smith had failed to separate fact from fiction.

And, as one evil never comes alone, there followed the devastating criticism of Sherman Kent, considered the “father of intelligence analysis.” Like Ryan, Kent categorically refuted the claim that a mere OSS operation in Lisbon had led to the alteration of Japanese codes and the loss of a crucial source of intelligence for the Allies.

Contrary to what had been reported by several authors, Kent vehemently argued that the case was used to exemplify the alleged “lack of discipline in the OSS.” Perhaps driven by the need to defend the honor that the OSS veterans themselves had apparently thrown out the window, Kent shared the thesis that the United States continued to decrypt a large part of Japanese military communications, before and after the alleged incident, demonstrating that the impact attributed to the operation was greatly exaggerated, if not completely non-existent. That said, he assessed the work as being the result of a serious lack of rigor, even accusing the author of having accepted a sensationalist version without due factual confirmation.

The truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth?

The time has come to set the record straight. Or at least an approximate version of the truth. Since we do not have all the documentary information on the subject, we will base our conclusion on the most complete account we have found, written by David Alvarez, entitled “Wild Bill” Donovan’s Comeuppance. We will start from the widely circulated version, with the aim of contradicting it and explaining what really happened.

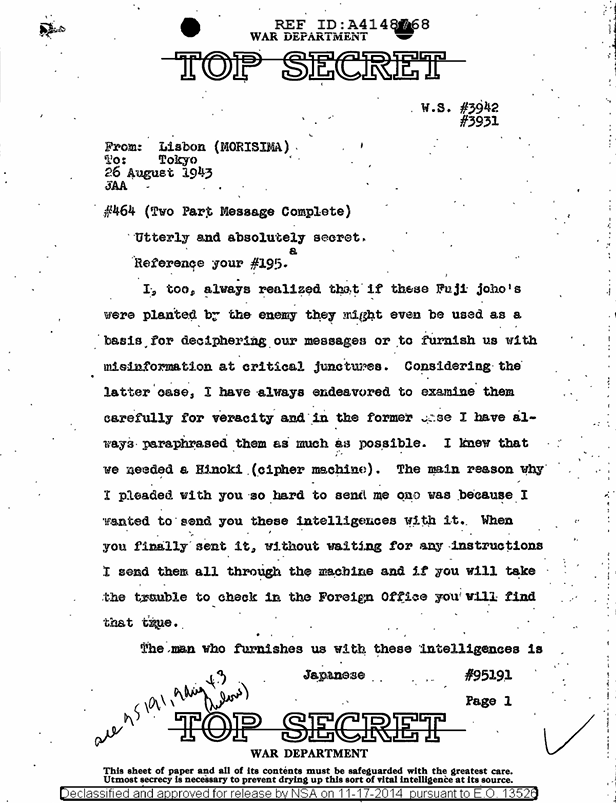

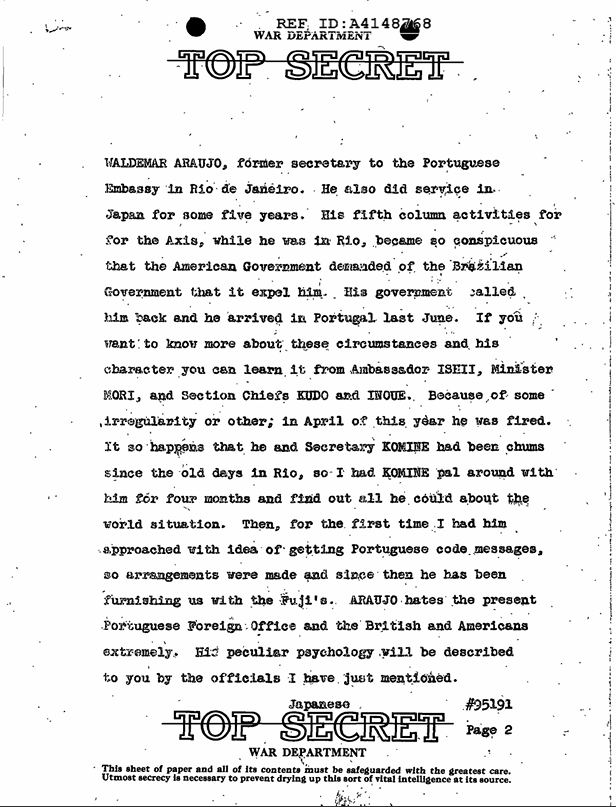

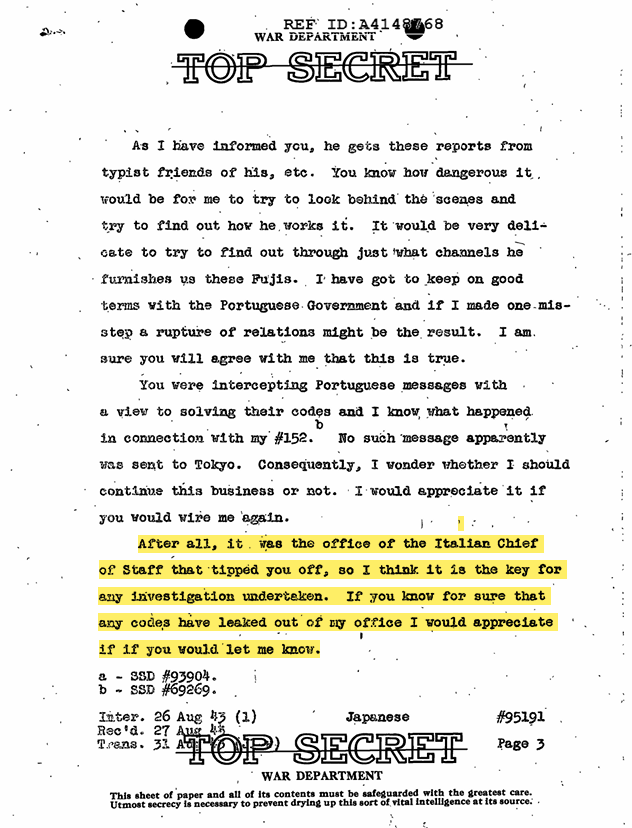

Unsure of the meaning of the symbols, the OSS sent them to Washington for analysis by the Signal Security Service, a top-secret Army code-breaking organization. The latter, in turn, concluded that they were low-level cryptographic systems with no significant strategic value.

However, Colonel Carter Clarke, head of the OSS’s Special Branch (the same man who, later, delivered the letter to Dewey at General Marshall’s request), saw this episode as a good opportunity to tarnish the OSS’s reputation. Described by Alvarez as a meticulous and suspicious man, Clarke remained firm in his conviction that this operation had exposed American efforts to decipher enemy codes.

Like a fever, this concern spread until it reached General George V. Strong, head of military intelligence. Moreover, both men harbored a deep disdain and distrust for Donovan and the OSS, their competitors. Infuriated, Strong accused the OSS of amateurism and of endangering national security.

His anger was, in fact, fueled by the same person who, coincidentally, gave the green light to the operation: diplomat George Kennan. Leaving his pride and backbone aside, he excused himself from any responsibility, completely omitting his involvement in this bizarre plot. It is said that, in fact, his lack of rigor may have led the Italian intelligence services to intercept coded telegrams from the State Department, which mentioned the operation in Lisbon.

However, the truth was much more complex than it seemed. Contrary to what many speculated, the OSS informant acted at his own risk. Furthermore, Japan’s decision to retire the cipher previously used was not a reaction to the alleged attack but part of a planned upgrade to its communications system. The analysis of the information confirmed, in fact, that Tokyo did not believe that the security of its embassy—a veritable nest of spies—had been compromised.

Driven by petty rivalries, Clarke and Strong chose not to release these statements. They preferred to let the case drag on for as long as possible, in order to tarnish Donovan’s personal and professional reputation, which from that moment on was never viewed favorably by the intelligence community. Strong’s anger may also have arisen from the British distrust of their Anglo-Saxon “cousins.”

The idea of such a major scandal, following the U.S.’s inclusion in the British war effort to decipher the German Enigma machine, could have jeopardized the fragile alliance between the two countries. Any suspicion that the Americans were acting independently, without consulting or respecting established protocols, would have been enough to undermine trust between the allies.

In the end, the OSS survived the storm, although its reputation was badly damaged. Donovan, an adventurous man accustomed to battle, forbade his men from searching for cryptographic material in the future. The damage had been done, however. Although unknown to most of the public, the Lisbon Affair left deep scars. The criticism that arose in the aftermath of the incident contributed to the dissolution of the OSS after the war, marking the end of an era in the history of intelligence.

And so, in that Lisbon of shadows and secrets, an operation that was poorly understood and poorly told over time became a symbol of the invisible battles that were being fought not only on the battlefields, but also in the corridors of Allied power, particularly in Washington. The truth, as so often happens, was lost between the lines of history, while the men and women who shaped it followed different paths, carrying with them secrets that would never have been fully revealed, were it not for the curiosity of stubborn journalists and writers.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Rafael Baptista is a 24-year-old journalist from Portugal driven by an unwavering passion for storytelling.

Curious and determined, he has spent over four years specialising in Politics and Security, investigating the rise of the far right and clandestine foreign espionage in Portugal. Inspired by Ryszard Kapuściński, Martha Gellhorn and many others, he is constantly on the move in search of extraordinary stories that transcend time.

Rafael can be reached at rafael.baptista2000@gmail.com.

Excellent article. Thanks for pointing out the horrific atrocities of the the NKVD.

The NKVD, KGB, and FSB, as historical and current Russian security agencies, have been involved in numerous criminal actions, including mass repression, political assassinations, and human rights abuses. These actions range from the Great Purge under Stalin, where the NKVD was instrumental in mass arrests, imprisonment, torture, and executions, to the KGB’s role in suppressing dissent and carrying out assassinations, and the FSB’s continued involvement in intelligence operations, counterintelligence, and border security, sometimes with questionable methods