Voters then, too, were faced with the choice of two corporate-backed candidates promoting regressive economic policies

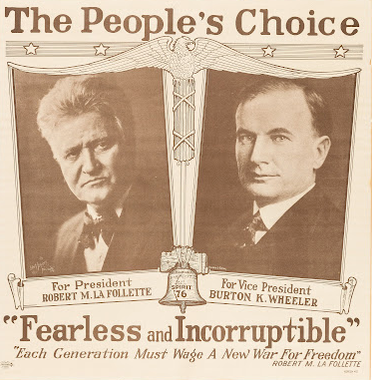

In 1924, at least, there was a genuinely progressive third candidate, Robert La Follette

The 1924 U.S. election was not much better than 2024’s. In both cases, the Republican and Democratic Party candidates had deep Wall Street ties and a track record of supporting dubious policies that favored the nation’s rich.

In 1924, both major-party candidates were connected with the J.P. Morgan Bank, a central force driving the U.S. into World War I after the State Department greenlit a loan that the bank provided to Britain and France to finance their armies.[1]

Historian Ron Chernow wrote that, in 1924, “the House of Morgan was so influential in American politics that conspiracy buffs couldn’t tell which presidential candidate was more beholden to the bank.”[2]

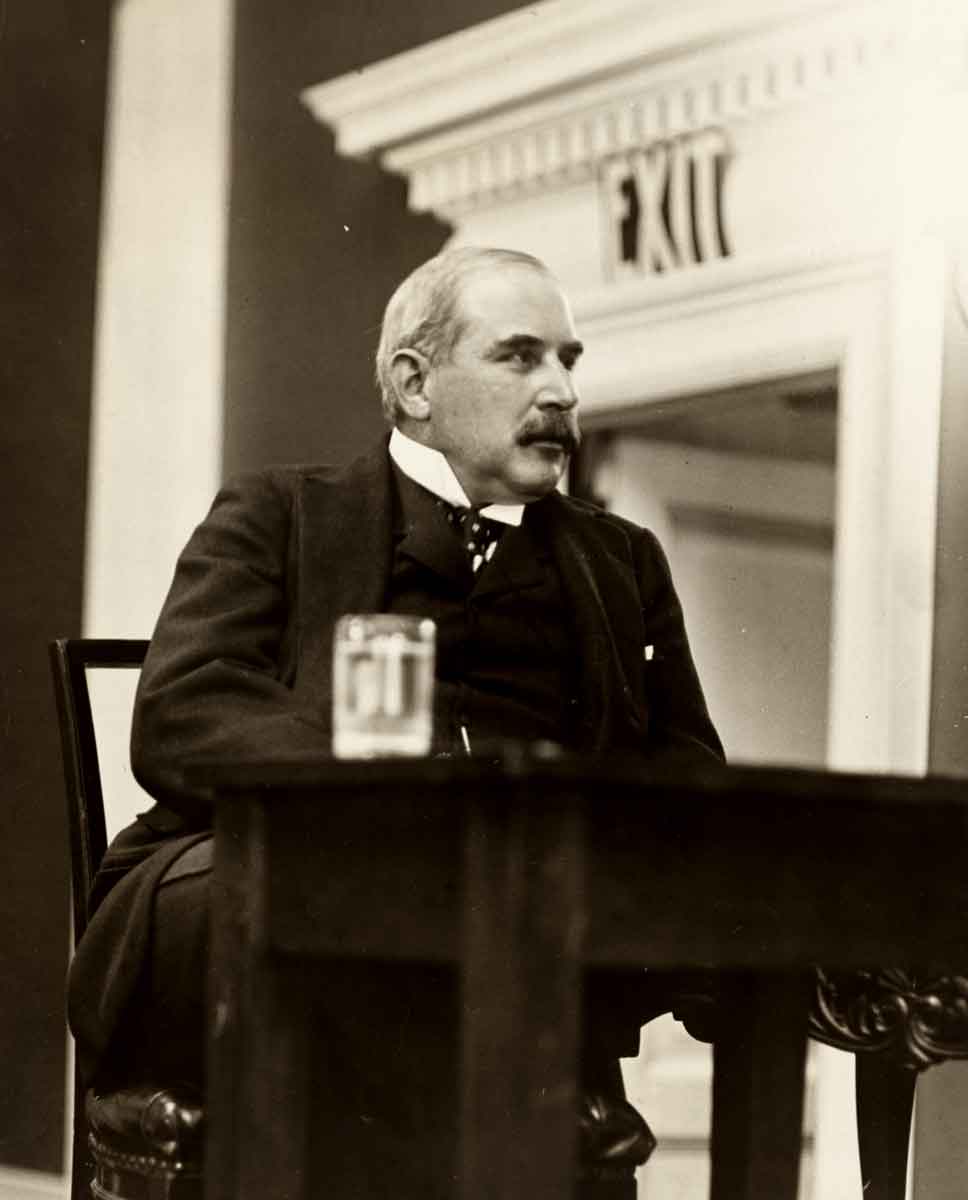

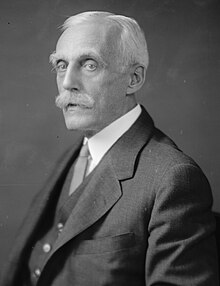

The Democratic candidate, John W. Davis, appears to have been most beholden to J. P. Morgan; he served as a senior partner in the law firm, Davis, Polk, Wardwell, Gardiner and Reed, that represented the Morgan group, and was J. P. “Jack” Morgan, Jr.’s neighbor on Long Island and backgammon partner.[3] One of the special favors that Davis did for Morgan was to lobby New York Governor Alfred E. Smith (1923-1928) to veto a bill to tax private bankers.[4]

A staunch defender of the British Empire who served as U.S. ambassador to Great Britain at the time of the Versailles conference that imposed a punitive peace on Germany, Davis was the first president of the Council on Foreign Relations, a think tank financed by J. P. Morgan and other Wall Street millionaires advocating for military and covert operations and other forms of intervention designed to open foreign countries to Wall Street investors.[5]

Davis gained the Democratic Party nomination after his main Ku Klux Klan-backed rival, William G. McAdoo, Woodrow Wilson’s son-in-law who had presided over the Federal Reserve System favoring private bankers, was disclosed to have received $150,000 to represent Edward Doheny, one of the architects of the Teapot Dome bribery scandal, in negotiation with the Mexican government over Doheny’s oil lands.[6]

Favoring a conservative economic program and states’ rights, Davis opposed women’s suffrage, federal child-labor laws, passage of veterans’ bonuses, anti-lynching legislation, and civil rights, and was a zealous hawk when it came to U.S. intervention in World War I.[7] In 1917, he accused anarchist Emma Goldman of “preying on the minds of the ignorant” while encouraging resistance to the Selective Service Act (i.e., the draft).[8]

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Arthur Krock wrote of Davis that he “greatly enjoyed his association with the rich” which “made him more conservative.”[9]

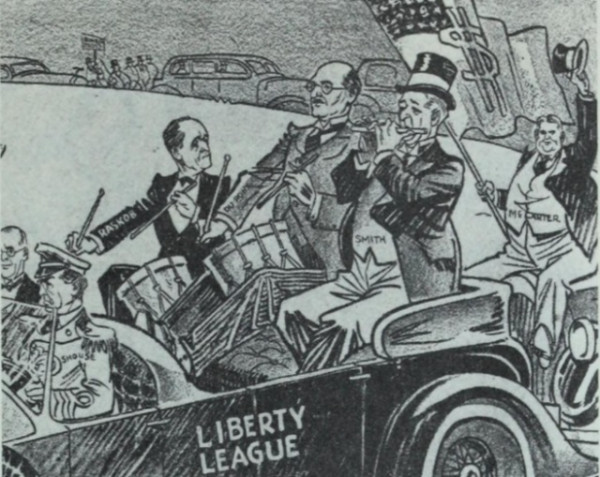

In the mid-1930s, he joined forces with Morgan, Irénée Du Pont, Alfred Sloan, Jr. (CEO of General Motors), Prescott Bush (George H. W. Bush’s father) and other one percenters in forming the Liberty League, which flooded the country with incendiary propaganda claiming President Franklin D. Roosevelt was introducing socialism in America with the New Deal.

The Liberty League plotted a coup against Roosevelt that tried to enlist retired General Smedley Butler, who implicated Davis in testimony before the McCormack-Dickstein congressional committee.[10]

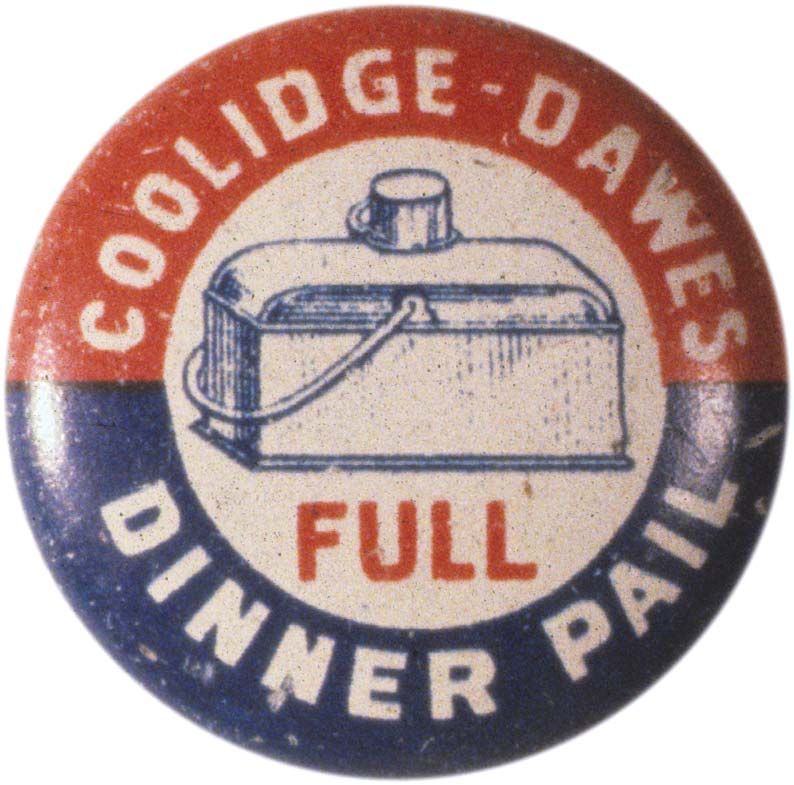

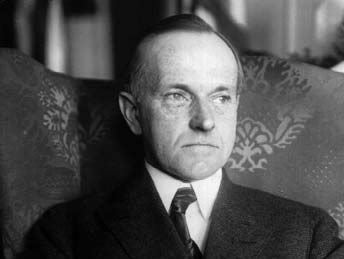

Davis lost the 1924 election by a resounding total to Calvin Coolidge, a hero of the modern-day conservative movement,[11] who was described by historians Henry Steele Commager and Alan Nevins as a “thoroughly limited politician, dour and unimaginative, thrifty of words and ideas, devoted to the maintenance of the status quo, and morbidly suspicious of liberalism in any form.”[12]

Another historian of the Cold War era, Samuel Eliot Morison, wrote in The Oxford History of the American People, that Coolidge was “the second of the three inept Republican presidents of the 1920s,” who was “mean, thin-lipped, mediocre, parsimonious, dour, unimaginative, abstemious, frugal, an admirer of wealthy men, reactionary, a cynical doubter of the progressive movement, and a democrat only by habit, not by conviction.”[13]

Coolidge had gained national prominence as governor of Massachusetts for breaking up a police strike in Boston that was rooted in poor police working conditions and abysmally low pay.

Coolidge quoted Woodrow Wilson, who claimed that the strike was a “crime against civilization,” and said that there should be “no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time.”[14]

Coolidge’s ties to Morgan were through his political godfather and former Amherst College classmate, Dwight W. Morrow, who was a partner in the J.P. Morgan firm and had served as chief civilian aide to World War I commanding General John J. Pershing.

Coolidge appointed Morrow—one of the richest men in New Jersey—as U.S. ambassador to Mexico, where he worked to prevent Mexico’s nationalization of oil fields controlled by U.S. corporations (like the Rockefeller owned Standard Oil) and the Morgan Bank.

In America’s Sixty Families, historian Ferdinand Lundberg said that Coolidge “exercised little discretion in catering to organized wealth” and “did what he was told by Morrow and Andrew W. Mellon.” Before Coolidge made any significant decisions, he would phone Thomas W. Lamont, another partner in the J.P. Morgan Company.[15]

J. P. Morgan, Jr., was himself an outspoken admirer of Coolidge who said that, “in his long life,” he had “never seen any President who gives me just the feeling of confidence in the country and its institutions, and the working out of its problems that Mr. Coolidge does.”[16]

Coolidge’s fundamental conservatism and adoption of red-baiting was illustrated by an article he wrote as Vice President for a women’s magazine under the title “Enemies of the Republic: Are the ‘Reds’ Stalking Our College Women?”[17]

The article railed against the formation of clubs for the discussion of radical literature and the hearing of radical lectures at women’s colleges like Smith, Vassar, Barnard, Simmons, Radcliffe, and Wellesley, and warned about the influence of the Socialist Review, whose editorial policy was “radical” and which “revealed a pro-Bolshevik leaning.”[18]

Coolidge concluded by stating that “adherence to radical doctrines means the ultimate breaking down of the old sturdy virtues of manhood and womanhood, the insidious destruction of character, the weakening of the moral fiber of the individual, the destruction of the foundations of civilization.”

This conservative outlook served the agenda of Coolidge’s wealthy backers like Andrew Mellon, one of the richest men in America who oversaw a banking and corporate business empire that included ownership stakes in Westinghouse Electric, Gulf Oil, Alcoa, the New York Shipbuilding Corporation and the Pittsburgh Coal Company.

A top donor to the Republican Party, Mellon served as Secretary of the Treasury from 1921 to 1932, where he pushed a conservative economic program that plunged the U.S. into the Great Depression.

At the core of the Mellon Plan was the reduction of income taxes on wealthy individuals by $6 billion. According to Lundberg, the details of the Mellon Plan—which John W. Davis privately supported—were worked out by S. Parker Gilbert, the assistant treasury secretary who was rewarded with a top job at J.P. Morgan & Co.[19]

The Mellon Plan involved the slashing of public services, cutbacks on regulations of big business and anti-trust laws that had been adopted during the Progressive era, and harsh measures against organized labor in order to keep wages low. Mellon, additionally, pushed for the adoption of tariffs that benefited his own companies, such as the Mellon Aluminum Company.

Andrew Mellon’s grandson Timothy, an heir to the family banking fortune who is worth more than $14 billion, continues to support the Republican Party financially. In the 2024 election, he was a top donor to Donald Trump, providing more than $100 million to him and other Republican candidates.

One Bright Spot

The one bright spot in the 1924 election was progressive third-party candidate Robert La Follette, who garnered 4.8 million votes (Coolidge won with 15.7 million and Davis received 8.3 million).

Endorsed by aging Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs, La Follette ran as an independent after leaving the Republican Party.

He had been a popular governor and senator in the state of Wisconsin, where he pioneered many progressive reforms that became a basis for national policy.

The latter included support for public education and anti-trust laws, and collective bargaining rights for labor unions, which became a model for the New Deal’s Wagner Act.[20]

Additionally, La Follette evolved as a strong opponent of U.S. militarism and imperialism. In November 1917, he gave a congressional speech in an attempt to convince his colleagues to oppose President Wilson’s deployment of U.S. troops into the Great War.[21]

On the campaign trail, La Follette told an audience of 10,000 in Boston that over the previous 20 years the United States had created “in Central and South America our Irelands, our Egypts and our Indias.” He continued: “Helpless peoples are being crushed into submission in order to compel them to pay tribute to our international bankers and industrial exploiters.”

La Follette further said that “American oil interests and concession hunters, with the aid of the State Department, are competing with the financial imperialists of England and France for control of the world’s resources.”

La Follette’s running mate, Senator Burton K. Wheeler (D-MT) was also an anti-imperialist who had a record of standing up to corporate power and supporting free speech. Early in his career, he had defended mine workers against the giant Anaconda Copper Company. In 1923, he also headed a Senate committee that exposed high-level corruption in the Harding administration, including the commission of bribery in the selling of oil leases (the Teapot Dome scandal).

Wheeler opposed not only U.S. intervention in World War I and World War II (he supported the America First Committee), but also protested against the U.S. Marine invasion of Nicaragua in the 1920s.[22]

Facing mob attacks, unfair media coverage and red baiting on the campaign trail, the La Follette-Wheeler ticket filled cavernous auditoriums on the campaign trail and was much stronger than any third-party candidate in 2024.

Endorsed by prominent writers and celebrities like W.E.B. DuBois, Jane Addams, John Dewey and Helen Keller, it advocated for government ownership of the railroads among other progressive economic measures.

La Follette and Wheeler were at a disadvantage in the 1924 race because of their difficulty in raising money on the level of the Democrats and Republicans.

A study of the 1924 election by historian Edward Ranson quoted from a government commission set up by Senator William Borah (R-ID), which found that La Follette and Wheeler raised $221,837 dollars and spent $22,977, whereas the Democratic Party raised $821,037 and spent $903,908, and Republicans raised $4,360,478 and spent $4,270,469.[23]

The latter figures go a long way in explaining Coolidge’s political success.

Ranson quoted from an editorial published in the Natchez Democrat entitled “Boodle in American Politics,” which deplored the influence of large cash donations in the election.

The editorial stated that the country must “abandon this wicked and dangerous habit of raising big campaign funds in America before politics could be cleansed.”[24]

These latter remarks are even more apropos in 2024 where campaign contributions totaled in the range of $21 billion.

The Republican candidate in this election, Donald Trump, was quite openly fascist, while the Democratic Party candidate, Kamala Harris, while Black and female, never won any primary and attacked Trump for attempting to engage in diplomacy with the North Koreans and Russians. She was also deeply complicit in the Israeli genocide in Gaza—as was Trump.

Perhaps, if they were transported in time to 2024, Coolidge and Davis[25] might advocate for some of the same kinds of policies as Trump-Harris, since most politicians are at their core opportunists and puppets of the financial oligarchy that FDR once said had “owned the government” since the days of Andrew Jackson.

As it stands, Coolidge and Davis appear to be at least marginally better than Trump-Harris who reflect the degradation of American politics in the 21st century.

See Roger Peace, Jeremy Kuzmarov, and Charles Howlett, “U.S. Participation in World War I,” October 9, 2018, https://peacehistory-usfp.org/ww1/. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan was forced to resign after he tried to block the loan from going forward, saying that it violated the Wilson administration’s neutrality policy. Bryan was replaced with Mr. Wall Street, Robert Lansing, the uncle of John Foster and Allen Dulles who sanctioned the loan going forward. Lansing was a mentor to John W. Davis. ↑

Ron Chernow, The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), 254. ↑

Garland S. Tucker III, The High Tide of American Conservatism: Davis, Coolidge, and the 1924 Election (Austin, TX: Emerald Book Co., 2010), 240, 241; William H. Harbaugh, Lawyer’s Lawyer: The Life of John W. Davis (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973). Appointed to the Board of the Rockefeller Foundation, Davis represented Morgan in 1933 when he was called to testify before the Pecora investigation into private banking and the causes of the Great Depression. Davis’s running mate in the 1924 election was Charles W. Bryan, the younger brother of William Jennings Bryan who was part of the more populist wing of the Democratic Party. ↑

Harbaugh, Lawyer’s Lawyer, 195. ↑

Laurence H. Shoup and William Minter, Imperial Brain Trust: The Council on Foreign Relations & United States Foreign Policy (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977); Harbaugh, Lawyer’s Lawyer, 157, 158. Davis expressed his belief that Britain was “not a land-grabbing institution but was engaged in the discharge of duties forced upon it.” He supported Britain in its colonization policies and the Middle East, while hoping that the British would open the Mesopotamian oil fields to American companies. ↑

Harbaugh, Lawyer’s Lawyer, 197. William Jennings Bryan, the former populist party leader who had been the Democratic Party nominee for president in 1896 and 1900, tried to block Davis’s appointment at the Democratic Party Convention, stating that “the convention must not nominate a Wall Street man….Mr. Davis is the lawyer of J.P. Morgan.” In addition to working for Morgan, Davis held directorships in the U.S. Rubber Company, American Telephone and Telegraph, the National Bank of Commerce and a couple of other corporations. ↑

Harbaugh, Lawyer’s Lawyer. Davis claimed, with regard to World War I, that “history showed ‘no blacker crime’ than the German attack on Belgium,” and said he “hoped that the tribal God of the Germans would slumber until a hundred drops of German blood shall have atoned for every drop drawn from the Belgians.” Consequently, Davis was elated after hearing President Wilson’s war message to Congress on November 2, 1917, stating that “I may live to be a hundred, but it is not likely that I shall ever witness a more thrilling scene or be more stirred myself.” (p. 123) Years later, Davis claimed that the revisionist historians’ attempt to read commercial influences into Wilson’s resort to war was “an insult to the president’s memory” and the Nye Committee exposing corporate war profiteering in World War I a “calculated effort to misrepresent the reasons” for Wilson’s action, which he called “one of the most amazing events in my lifetime.” This supposedly amazing event resulted in the deaths of 53,000 American youth in combat (another 63,000 are estimated to have died in the war from accidents and diseases) and led directly to World War II. (p. 422) In a statement that he drafted on behalf of the banking firm in 1936 in response to the Nye committee which had called on Morgan to testify, Davis claimed that the House of Morgan were not profiteers but visionaries who realized that “a German victory would have destroyed the freedom of the rest of the world.” ↑

Harbaugh, Lawyer’s Lawyer, 125. Davis predictably supported the persecution of war dissenters like Goldman and other leftists under the 1917 espionage and sedition acts. ↑

Harbaugh, Lawyer’s Lawyer, 267. ↑

Tucker III, The High Tide of American Conservatism, 274. In his last legal case, Davis—who supported Republican Alf Landon in the 1936 election against Roosevelt and tried to overturn many pieces of New Deal legislation in the courts—adopted the argument of states right in trying to block the integration of public schools in Briggs v. Elliott, a companion case to Brown v. Board of Education. To his credit, Davis in the twilight of his career stood up for Alger Hiss and J. Robert Oppenheimer during the hysteria of the McCarthy era. However, he had supported Truman’s Cold War policies, blaming the outbreak of the Cold War on the Russians whom he believed “have the same secrecy, the same distrust of foreigners, the same ambition for expansion they had under the czars.” Davis in turn supported rearmament of Germany, military aid to Greece and Turkey and George F. Kennan’s containment strategy, and gave his name to the Citizens’ Committee for the Marshall Plan. Davis advised Truman against intervening in Korea. Before his death he also warned against intervention in Indo-China. Harbaugh, Lawyer’s Lawyer, 430, 431, 432, 433. ↑

See Tucker III, The High Tide of American Conservatism. ↑

Henry Steele Commager and Alan Nevins, A Pocket History of the United States, 6th ed. (New York: Pocket Books, 1978), 405, 406; Thomas B. Silver, Coolidge and the Historians (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1982), 4, 5. ↑

Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People (New York: Oxford University Press, 1965), 933-934; Silver, Coolidge and the Historians, 4, 5. ↑

See Francis Russell, A City in Terror: The 1919 Boston Police Strike (New York: Viking Press, 1975), 191. ↑

Ferdinand Lundberg, America’s Sixty Families (New York: The Citadel Press, 1960), 149, 150. Lundberg quoted Senator Medill McCormick (R-IL), part owner of the right-wing Chicago Tribune, who characterized Coolidge as a “boob.” ↑

Tucker III, The High Tide of American Conservatism, 240. ↑

Lundberg, America’s Sixty Families, 150; Calvin Coolidge, “Enemies of the Republic: Are the ‘Reds’ Stalking Our College Women?” 98, The Delineator, June 1921, 4-5, 66-67. ↑

Coolidge was most pleased with Mt. Holyoke College, where he said that the radical books in the library were used mainly as references in economics courses and that the book “The Case Against Socialism” was most widely used. The same he said largely held true at Bryn Mawr where there was no socialist club or listed course in socialism. Though one member of the leftist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) once spoke there, there was not much reported interest in “radical utterances.” Coolidge though was horrified by Wellesley College outside Boston where one of the executive board members of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, Vida Dutton Scudder, gave courses, where books on socialism at the library “showed considerable use,” and where an article in the student magazine in 1918 commended German socialists who, during the war, opposed war loans, and stated that the “bolsheviki [Russian revolutionaries] have kindled a new torch of democracy and are brandishing it aloft to enlighten the world.” Radcliffe was also disturbingly called a “hotbed of socialism.” Coolidge lamented editorials in The Radcliffe News criticizing the arrest and deportation of what Coolidge termed “undesirable aliens” in the first Red Scare; criticizing attempts to exclude five socialists from the New York State Assembly, and defending Harvard Professor Harold J. Laski for expressing his sympathy for and support for Boston police officers who had gone on strike. Coolidge also lamented that, at an intercollegiate debate, Radcliffe students had argued that “recognition of labor unions was essential for successful collective bargaining.” ↑

Lundberg, America’s Sixty Families, 150. Davis’s support for the Mellon Plan is discussed in Harbaugh, Lawyer’s Lawyer, 196. ↑

See David P. Thelen, Robert La Follette and the Insurgent Spirit (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1986). ↑

Tucker, The High Tide of American Conservatism, 226; Richard Drake, The Education of an Anti-Imperialist: Robert La Follette and U.S. Expansion (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013). La Follette believed that World War I had “openly enthroned Big Business in mastery of government” in the U.S. On April 4, 1917, La Follette spoke for 165 minutes emphasizing that: the majority of U.S. citizens did not support war; the U.S. had failed to pressure Britain to end its blockade thereby inviting a German response; other neutral nations had not entered the war; and Britain had shown no inclination to extend democracy in any part of its empire, including Ireland. “The failure to treat the belligerent nations alike,” he said, “to reject the illegal war zones of both Germany and Great Britain, is wholly accountable for our present dilemma.” La Follette asserted that the president, rather than admitting his policy failures, was trying to “inflame the mind of our people into the frenzy of war.” ↑

See Marc C. Johnson, Political Hell-Raiser: The Life and Times of Senator Burton K. Wheeler of Montana (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019). For more on the La Follette-Wheeler ticket and 1924 election, see also Oswald Garrison Villard, Fighting Years: Memoirs of a Liberal Editor (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1939), 502-505 and the discussion in Nathan Masters, Crooked: The Roaring ’20s, Tale of a Corrupt Attorney General, a Crusading Senator, and the Birth of the American Political Scandal (New York: Hachette, 2023).↑

Edward Ranson, The American Presidential Election of 1924: A Political Study of Calvin Coolidge, book 2 (Lewiston, ME: Edwin Mellen Press, 2008), 717. ↑

Ranson, The American Presidential Election of 1924, 717. ↑

Davis was actually critical of Harry S. Truman’s support for the State of Israel at its formation in 1948 and called for a balanced policy with the Palestinians. Harbaugh, Lawyer’s Lawyer, 432. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.