“The Mafia is not an outsider in this world; it is perfectly at home. Indeed, in the integrated spectacle it stands as the model of all advanced commercial enterprises.”

—Guy Debord

In early June 2025, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) released four documents that had been sealed for 50 years. DEA Agent Andrew Tartaglino, a 25-year veteran of federal drug law enforcement, had entered them into public hearings held before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in June 1975.

The four documents were the result of seven years of investigations, led by Tartaglino, into corruption within the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN). Partially as a result of the rampant corruption with its ranks, the old FBN was dissolved in 1968 and reconstituted as the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD). The BNDD evolved into the DEA in 1973.

Subcommittee Chairman Henry Jackson (D-WA) said about the documents in 1975: “We will receive them and place them in a sealed envelope. They will be…treated confidential until such time as it would be appropriate to make them public.”[1]

One document, Exhibit 14A, dated November 21, 1968, and titled “Integrity Investigation—New York Office, History, Recommendations and Conclusions,” tells how fellow FBN agents reportedly tried to murder FBN Agent Ed O’Keefe in February 1959. This article is about O’Keefe and the implications of his case.

I first heard about the murder attempt on Ed O’Keefe in Jill Jonnes’ book Hep-Cats, Narcs, and Pipe Dreams: A History of America’s Romance with Illegal Drugs (New York: Scribner, 1996). Quoting directly from Exhibit 14A, Jonnes said that, on the night of February 7, 1959, cops from the 43rd Precinct were summoned to Watson’s Bar in the Bronx, where they found an FBN agent comatose on the floor.

The agent was rushed to Jacobi Hospital where doctors determined he had had an overdose on a narcotic drug. No needle marks were found on his body, but heroin was found in his car. The agent, Jonnes said, resigned within 36 hours.

The motive, according to Jonnes, citing FBN inspectors, was that the agent had approached two heroin traffickers and tried to sell them information on a case pending against them without clearing it with his corrupt bosses in the FBN’s New York office.

For 20 years, I tried to pry the four documents out of the Senate, even after I located Ed O’Keefe in Michigan in 2015 and began collaborating with him on this article. As I explained to the Senate archivist, Exhibit 14A may well have named the agents who poisoned O’Keefe.

No one at the Senate budged. But within days of sending my emails to various government officials in 2015, I was contacted by Phil Manuel, the former military intelligence agent who headed the Permanent Subcommittee’s investigation in 1975.

Manuel, who was working with Hollywood executives on a movie about his life, asked if I would send him copies of my two books on the history of federal drug law enforcement, The Strength of the Wolf and The Strength of the Pack. https://www.douglasvalentine.com/events.htm

Perhaps Manuel’s sudden appearance and request for my books was coincidence. In any event, the attempt on Ed O’Keefe’s life provides significant insights into the criminal machinations of our government and its relationship with organized crime and the CIA.

On the following pages I will offer some reasons for why they are still covering up the attempt on Ed O’Keefe’s life back in 1959.

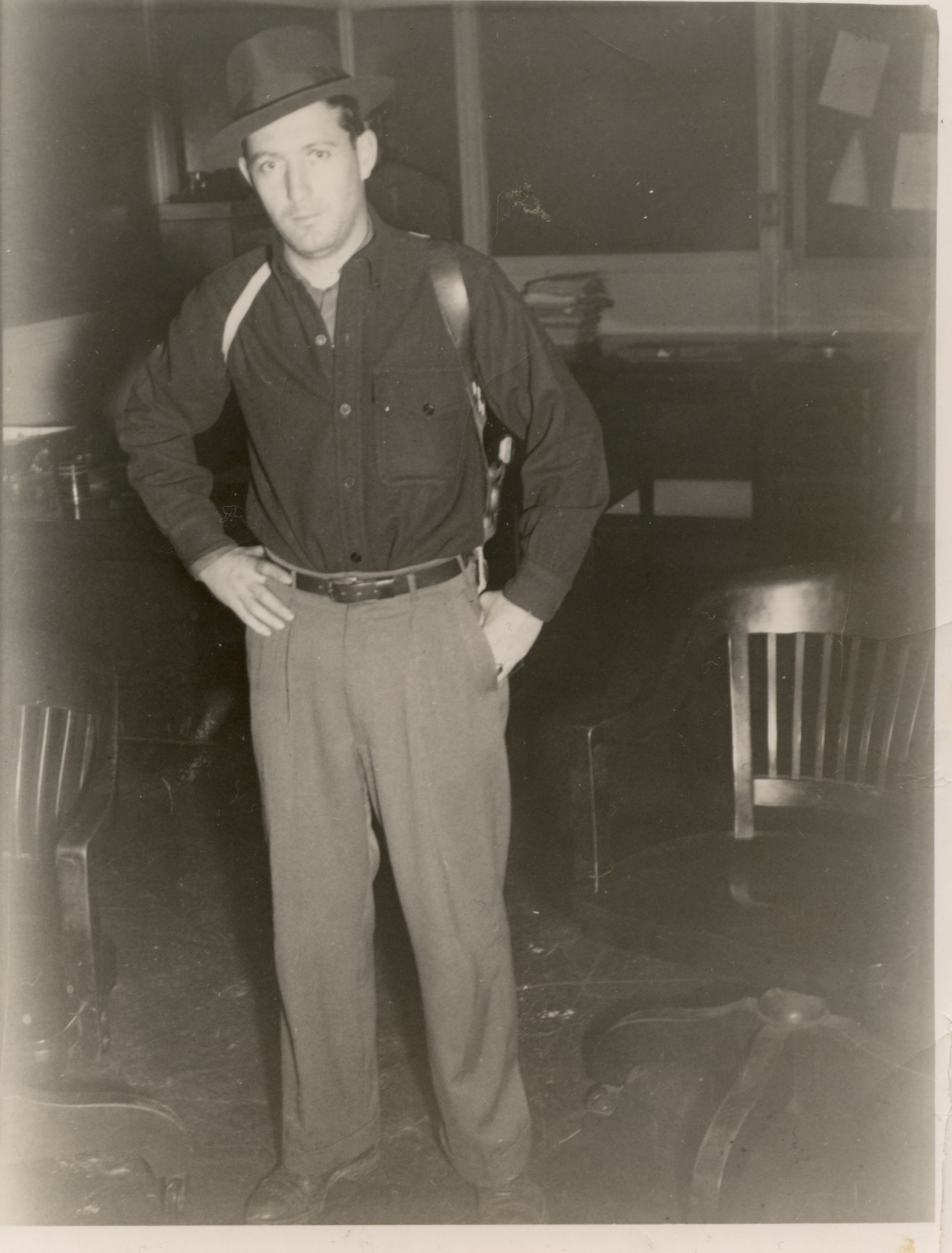

Introducing Ed O’Keefe

Ed O’Keefe, who passed away in 2021, was a successful businessman and owner of the Chateau Grand Traverse winery in Michigan. He grew up in an Irish section of Philadelphia, attended a Catholic high school and graduated in 1949. A talented athlete, he toured Europe representing the United States on the national gymnastics team in 1950. In 1951 O’Keefe enlisted in the U.S. Army’s Special Forces.

After being released from active duty in 1953, O’Keefe earned a B.A. in Health Education and entered the University of Miami Law School with the intent of becoming an FBI agent. But he was bored and applied for a job with the FBN instead. The FBN district supervisor in Atlanta, George Gaffney, conducted the job interview and hired him in 1958.

O’Keefe was sent to the Treasury Law Enforcement School in Washington, D.C. He became a criminal investigator working first in the FBN office in Philadelphia and then, starting in August 1958, the FBN office in New York City. The Big Time. Big things were happening too, including a reorganization within the Mafia as a result of the indictment on drug-trafficking charges of Vito Genovese, boss of one of New York’s fabled Five Families, and more than a dozen co-conspirators in July 1958.

O’Keefe and his family initially moved into an apartment in the Bronx not far from Watson’s Bar. And like every FBN agent, O’Keefe was looking to make cases. But in order to make cases, he needed a source of information, so he began combing through the officially restricted but wide-open informant files in the New York office on 90 Church Street. Soon he found a violator serving time in a federal prison in Connecticut. In exchange for “consideration” (meaning the possibility of a reduced sentence), the prisoner provided O’Keefe with access to an informant who helped O’Keefe make cases in African-American neighborhoods in New York City.

When not making cases through his informant, O’Keefe joined with other agents kicking down doors in Harlem, preying on Black addicts who, in the days of segregation, had virtually no legal protection. The ultimate goal was to find a Black addict who could initiate cases that would lead FBN agents back up the chain of command to the top Mafia bosses.

O’Keefe was busy making small cases until November 1958 when his senior partner, James Doyle, called to say that Mafia drug trafficker Joseph DiPalermo, who had been indicted along with Vito Genovese and 15 other drug traffickers, had been spotted at the Copacabana Club on West 47th Street. Doyle told O’Keefe to meet him outside the Copa, where they took DiPalermo into custody. And that is when things started to go sideways.

Joey Beck

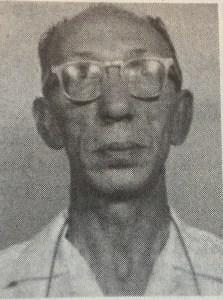

Joey DiPalermo, aka Joey Beck, was born in 1907 in New York City. A member of the Thomas Lucchese Family, Beck had been arrested and imprisoned multiple times since 1925 for various crimes. Short, balding and bespectacled, he looked like a geek but, in 1943, he and Carmine Galante, a ranking member of the Bonanno Family, were “suspected” of murdering socialist firebrand Carlo Tresca. The murder occurred at a time when the government had formed an alliance with underworld gangsters who were asked to search for enemy saboteurs and prevent labor strikes on the Waterfront.

After being released from a five-year prison sentence for forging travelers checks, DiPalermo in 1955 became a central player in the smuggling of massive amounts of heroin into the U.S. from France through Cuba, Puerto Rico and Mexico. It was a member of this operation, a Puerto Rican named Nelson Cantellops, who had been arrested by the FBN and, to avoid going to prison, had ratted out Genovese, DiPalermo, and more than a dozen of their accomplices. Apart from transporting narcotics from Florida to New York City, Cantellops transported narcotics to Las Vegas, Cleveland and Chicago. He knew everyone involved in the conspiracy.

DiPalermo was at the heart of the smuggling and distribution operation. He lived at 246 Elizabeth Street near the gang’s “plant” at 36 East 4th Street, where the imported heroin was cut and prepared for distribution. The gang also used policy banks in the Eldridge Street area on Manhattan’s Lower East Side as fronts for its narcotics distributing plants.

“Please note Doyle was my senior partner, “O’Keefe stressed in one of our correspondences in 2015. “I was the new guy on the block and this was the most significant thing Doyle and I ever did together.

“Doyle and I arrested Joe at the Copa early Sunday morning and because I was the junior agent, I was the one that guarded him at the Federal Courthouse. They kept Joe in the witness room while he waited to go before the judge. And while I was in the room with him, alone, Joe tried to pump me for information. The room was bugged, so I put my fingers to my lips, shook my head and pointed to the ceiling. I didn’t want to talk to him without a witness. But he must have thought I was trying to help him.”

After he was released on bond, Joey DiPalermo continued to believe that Ed O’Keefe was his friend. As O’Keefe explained, “While on surveillance a short time later in the Canal Street area, I stopped off at a Prince Street bar to satisfy my curiosity before I went home. When I entered the bar, I was surprised to be greeted by Joe, who exclaimed: ‘Ed O’Keefe, my good friend. How are you? Have a drink and meet my girlfriend, Jean Caprese.’

“He brought me over to meet her. She was sitting on a bar stool and as I approached, she reached over and opened my jacket. ‘I want to see if you have a wire,’ she said. It wasn’t a quick movement and I didn’t think much of it at the time. I couldn’t blame her.

“Joe and I had a friendly conversation,” O’Keefe recalled. “He wanted to know who was informing on Genovese. He offered me things. He said he’d get me a job down at the docks and I’d make a lot more than I made now. I told him that wouldn’t work. He said, ‘What if you were walking and found a roll of bills in the gutter?’ I said agents don’t find a roll in the gutter.

“I wanted to get out of there quickly, but his brother Charlie came over and Joe introduced him to me. He said, ‘Charlie, look at this kid, he wants to help me and doesn’t want anything.’ Then he invited me to his apartment, along with Charlie and Jean. I decided to go, to see what I could learn. It was surreal. We had tea and donuts. They made another pass at me, and I said, ‘Look, Joe, I have to get home, let me think about it.’

“Joe told Charlie to give me his phone number and I said I’d phone him tomorrow if I could find out something. I left and drove home. The next morning I wrote my daily report about the whole affair. George Gaffney (who had left Atlanta and was now the district supervisor at 90 Church Street in New York City) and Pat Ward, his enforcement assistant, called me into his office and said I didn’t have enough experience to be dealing with a Mafioso as important as DiPalermo.

“They said that I was jeopardizing the case they were working on. Ward told me to call Charlie DiPalermo then and there, and while I did it, all my superiors listened in. I told Charlie there was no way I could find the person who had informed on Genovese. And at the time I truly did not know who it was.

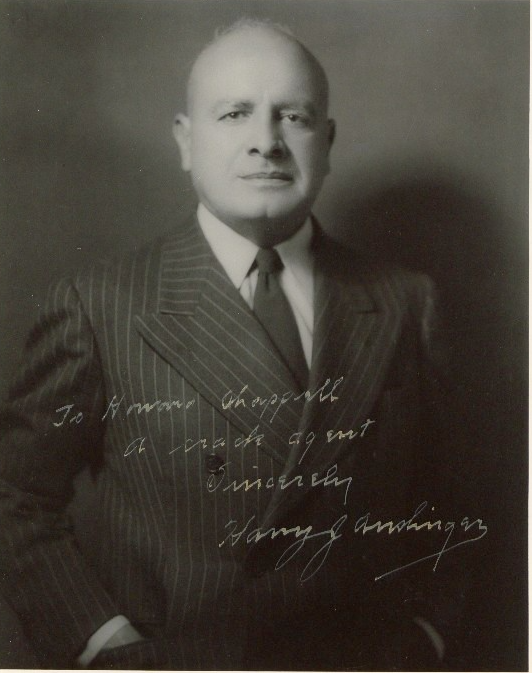

“Charlie offered me another bribe on the phone and I’m sure, if we had followed through with this, we would have made a much stronger case against the Genovese family. But instead of being told that I did a good job, I was told that, from then on, I had to write a daily report of everything I did. Those daily reports were sent directly to Commissioner Harry Anslinger in Washington.

“This went on for a month or more, into December. Then for some reason they informed me that I was being sent to Washington to speak directly with FBN Commissioner Anslinger and his chief inspector, Charlie Siragusa. I had three young children and, with a GS 7 salary, I simply couldn’t hire a lawyer. So I did the next best thing and told my bosses that I was bringing a Congressman along. I wanted to see if the matter would go as far as Washington. I had no idea at the time it would get that far.

“So when I got there to the Commissioner’s office, Anslinger asked, ‘Where’s the Congressman.’ When I told them there wasn’t any, they were surprised. Then Siragusa said,

‘How could you let this woman pull your jacket open.’

‘Like this,’ I said, and reached over and opened his.

“It wasn’t a big thing. But it was apparent to me that they wanted to see who the Congressman was. I don’t think the meeting was really about me. Anyhow, after this I went back to work and the other agents told exaggerated stories about what happened in the bar with Joey and down in D.C. They said that Jean Caprice had stolen my badge and gun on Prince Street, and that that’s what Siragusa wanted to discuss in D.C.”

Watson’s Bar

Although a productive agent, the veteran agents did not trust O’Keefe. Given that District Supervisor Gaffney had personally recruited him and brought him into the New York office, some of the agents suspected that he might be a shoofly—an agent who had gone over to management and was spying on them.

“The agents there didn’t trust me,” O’Keefe explained. “Whenever I approached a group of them outside the office on Church Street, they’d stop talking or break up their meeting. So I had to develop reliable information on my own to make cases. That’s what it’s all about, but I got a reputation as a loner.

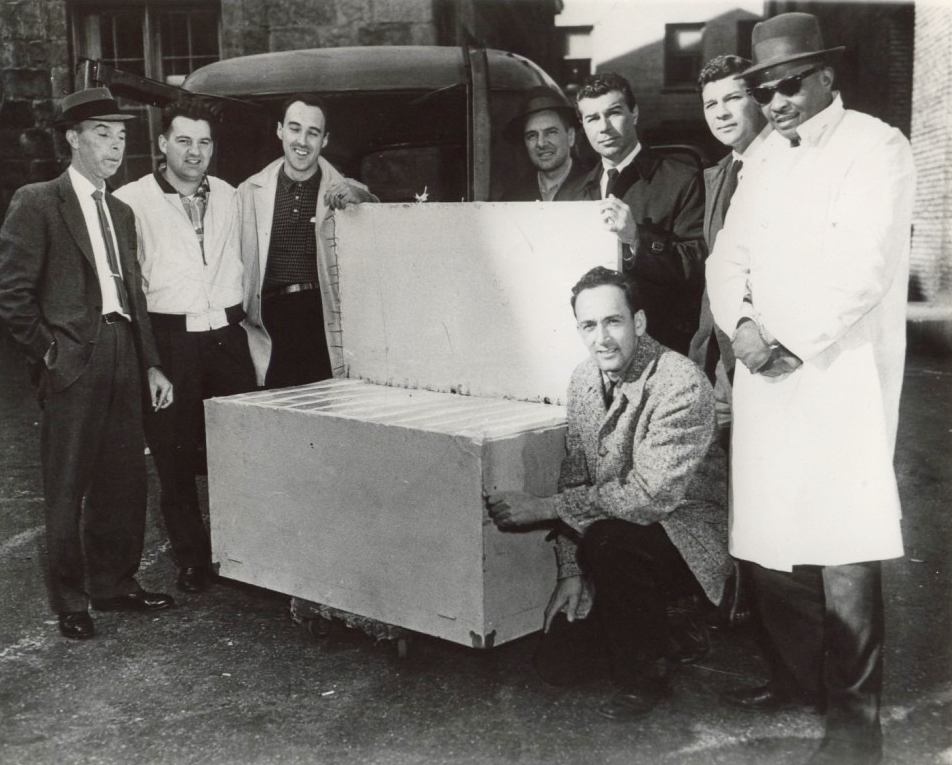

“It all came to a head in February while I was up in the Bronx, working on a case as a surveillance agent along with Agents Howard Diller, Joe Stone and Henry Brentari. An undercover agent, whose name I forget, made a buy. It was a Friday night. We sealed the heroin in a brown container that was impossible to open without destroying the container. The evidence container was signed by all four of the agents.”

O’Keefe said that he put the evidence in a hiding place in the glove compartment and his weapon in the trunk and went into the Watson Bar on Underhill Avenue to call his wife and tell her that he’d be heading home soon, right after he went to the office to turn in the evidence.

“None of the other agents went into the bar with me,” O’Keefe added. “Where they went, I don’t know.”

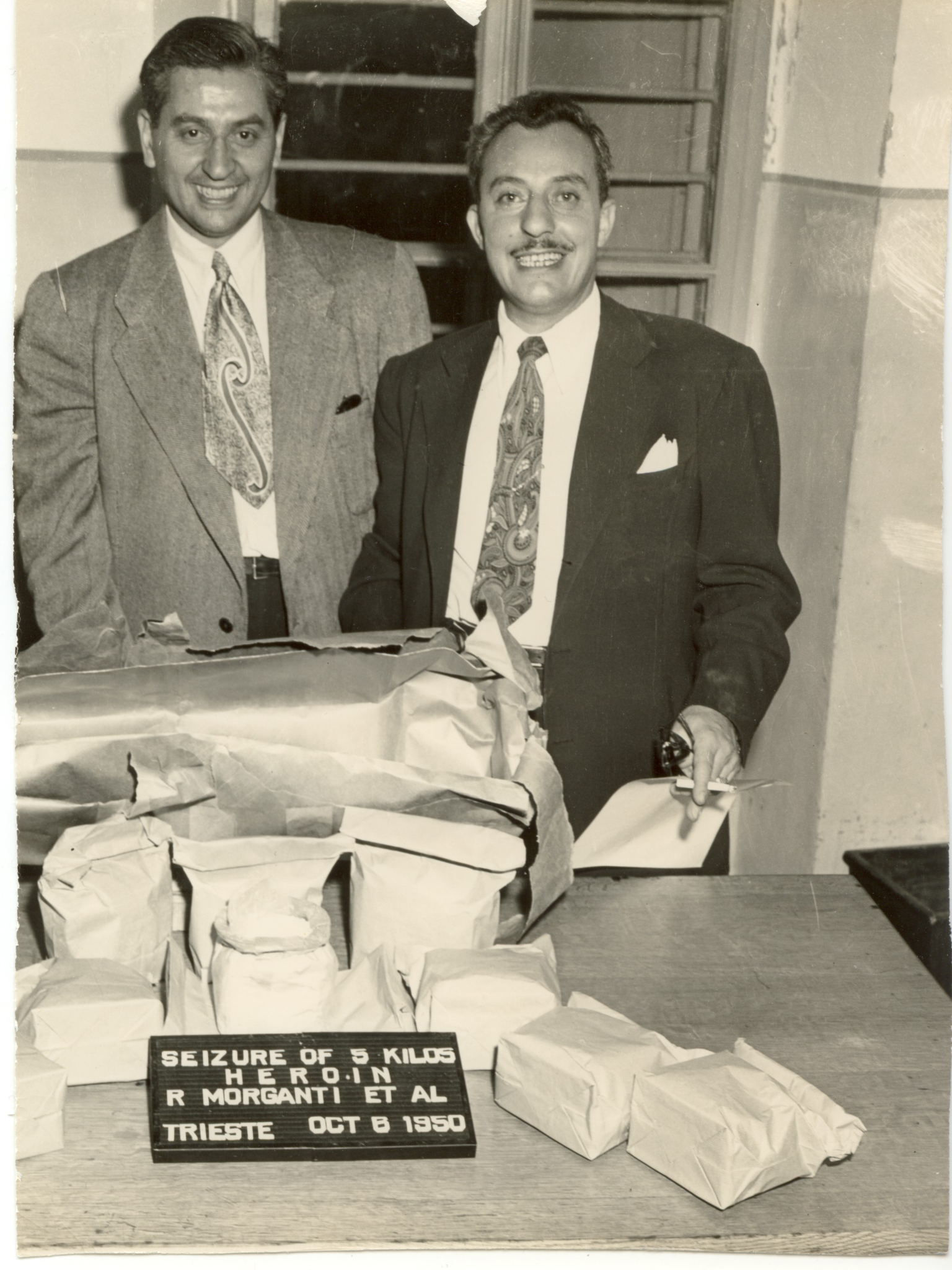

Andrew Tartaglino’s 14A report claims that O’Keefe was with Agents Diller, John Dolce and Raymond Maduro, who had been an agent for only three months at that time and may have made the undercover buy at a bar in Brooklyn that night. The report also claims O’Keefe drank seven or eight beers that night at the Brooklyn bar.

“Inside Watson’s, I bought a beer and drank some before I went to the back where the telephone was. I left the glass on the bar and lost sight of anybody that might have put something in it. After I called my wife, I went back to the bar and finished my drink. And that’s the last thing I remember until I woke up in Jacobi Hospital with a group of agents standing around me. I was on an operating table with a bright light shining in my face, so I couldn’t see who was there. I asked what had happened and they deluged me with questions, and I passed out again during this questioning.

“Monday, when I got out of the hospital and went to the office, I was brought into Pat Ward’s office and he told me that they wanted me to resign.

“I realized my career with the Bureau was over. There was no doubt in my mind that as bad as things were, they could get considerably worse. So I resigned and moved my family to Detroit, where I had already secured a job.”

The 14A Version

As one can see by reading pages 3 and 4 of the 14A report (see appendix), O’Keefe’s version is at odds with what was reported. 14A says that: 1) he tried to sell information to the DiPalermo brothers; 2) Congressman Francis Dorn (R-NY) did intervene on O’Keefe’s behalf; 3) O’Keefe bragged about having using Dorn to back off FBN management; 4) he and Agents John Dolce, Diller and Raymond Maduro were together that night; and 5) heroin was found secreted in the glove compartment. [NOTE: It’s difficult to “read” pages 3 and 4 of the 14A report since there is no citation for any of the four documents.]

The final conclusion, given by District Supervisor George Gaffney, was that O’Keefe had given himself an OD.

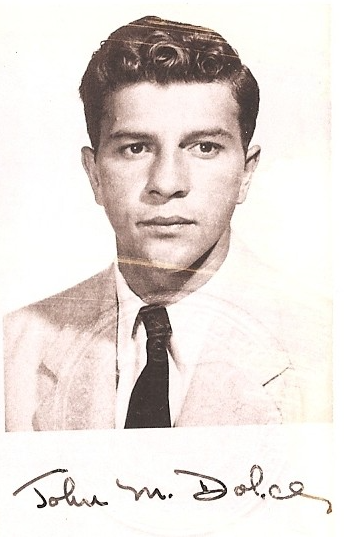

One discrepancy that stands out from all the others is that John Dolce was allegedly present that night. Described as “smart and sophisticated,” Dolce became leader of what became called Group Three in August 1960. That same month, Agent Charles Thompson was found dead at home. (See “The Thompson Incident” on pages 4 and 5 of 14A.)

Thompson had told his wife earlier that evening that he had been given a shot of narcotics by a doctor. “Reliable informants,” according to 14A, said that Thompson “was given an oral overdose of morphine and arsenic by an Informant of John Dolce called ‘Black Johnny.’”

Black Johnny was also said to have been involved, a few years later, in the murder of Tilton Rosa, a narcotics courier.

An investigative report about corruption in NYC in 1961 said that Group Three, then under John Dolce, led the office “in the exaggerated reporting of seizures,” and it criticized Gaffney for not insisting that regulations be followed. It also said that nine agents had improperly given money to informants and recommended that they be demoted or suspended. They were not. And corruption not only continued, it exploded.

FBN Agent Lenny Schrier says the troubles started in 1962. “There was a guy from East Harlem, Georgie Farraco, selling to Blacks. Artie Fluhr was on night duty, and he gets an anonymous call about a load going to Farraco’s apartment. It sounded good so we decided to hit him. I remember that night very well. Artie called me up and said, ‘Bring your Kaopectate and your gun.’ So we arrested Georgie and when we arrested him, he said, ‘You’ll hear from somebody.’ And sure enough the next day (FBN Agent) Patty Biase’s waiting in the hall. He points to Farraco and says, ‘He’s with me.’ Well, a few weeks later they find Georgie’s car double-parked. It’d been there twenty-four hours. Seems somebody told on him.

“The next incident occurred about a year later and involved Frank Russo. Russo’s a good informant, but to be a good informant, he has to sell narcotics. The only way you can make cases is if your informant sells dope. But you have to protect him. You can’t let him sell dope to another agent’s informant, and you can’t introduce him to an undercover agent. So I met him alone and only my group leader, Ben Fitzgerald, and the enforcement assistant Pat Ward, knew that Russo was mine.

“John Dolce ran Group Three, then became the enforcement assistant. Dolce was a good agent,” Schrier says with respect. “He was my only competition. But he was ‘in’ with Ward and Gaffney, and he had adopted Patty Biase. So Ward tells Dolce, and Dolce tells Biase, and that’s how Biase found out that Russo was my snitch. This was in 1963 and I’m still making cases with Russo. But Biase didn’t warn Russo off when he had the chance, so Frank got killed. He was stomped to death in an alley outside a pool hall on 108th Street. When they found his body, rigor mortis had already set in. His face was contorted and he was lying on his back with his arms and legs up in the air.”

According to FBN reports, 27 FBN informants were murdered as a war broke out among the FBN agents. Many New York agents resigned in despair. One agent who resigned was Robert J. Furey. A former State Trooper, Furey had investigated Black Muslims, Cuban gunrunners, and political subversives, and he was no ingénue when he entered the FBN in 1959. “I went into the Third Group under John Dolce,” he recalls, “and in less than a year it was clear that what was going on in New York was beyond the comprehension of the bosses in Washington.”

For Furey, the last straw was the murder of informant Shorty Holmes on August 8, 1961. Holmes was a key witness in an important case on several major Mafiosi. He was found mutilated and stuffed in a garbage can. “The world was collapsing around my head,” Furey recalls, “so I and a few other agents transferred out. People went to the State Department, or to ATF, or to Customs. Everyone was afraid of seeing or hearing the wrong thing.”

In 1963, John Dolce became the enforcement assistant to the new District Supervisor, George Belk. When he resigned from the FBN, Dolce became chief of Public Safety in Westchester County. He would not talk to me.

Gaffney’s Version

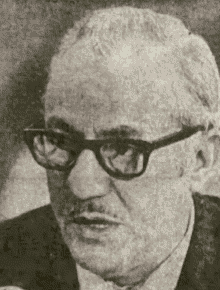

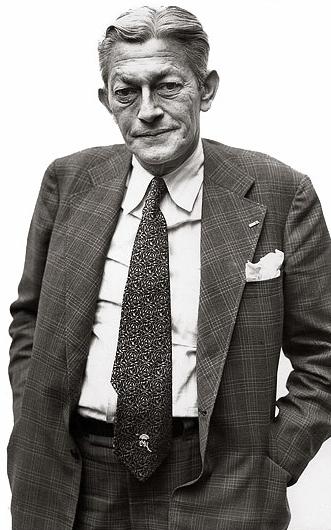

A Naval Academy graduate, George H. Gaffney served as a navigator on the USS Missouri during the Second World War. But his real interest was intelligence, so he resigned his commission and sought work with the CIA, which ostensibly rejected his application. The FBN hired Gaffney in 1949. Charlie Siragusa was his first group leader. Charles “Pat” Ward was his senior partner.

Driven to succeed, his path paved by benefactors, Gaffney became the FBN’s youngest district supervisor in Atlanta in 1956 and, in late 1957, was named district supervisor in New York, the FBN’s premier post. During Gaffney’s four and a half years heading the New York office, the FBN made landmark cases on top members of four of the Mafia’s five fallen families, as well as two spectacular “French Connection” cases.

While New York’s district supervisor, Gaffney, notably, oversaw a CIA safehouse at 105 West 13th Street, which had been furnished by Andy Tartaglino and his mentor Charlie Siragusa. Siragusa then introduced Gaffney to CIA officer Ray Treichler at a restaurant in New York. Gaffney recalls that Treichler spoke with a British accent, wore a derby hat, carried an umbrella, and gave him specific instructions.

He said the CIA had priority over the safehouse, that Siragusa would call him when the CIA wanted to use it, and that he should keep the FBN agents away when that happened. Gaffney was also told to make the apartment look “lived in.” In compliance with this second instruction, the 13th Street pad became a convenient place for FBN agents to make cases, quiz informants, and have parties. It was also a place where out-of-town agents, family members, old friends, and dignitaries could stay while in New York.

Few agents knew that the mysterious apartment was funded by the CIA, and its existence fueled rumors that headquarters was involved in corruption—that the bosses, perhaps, were receiving “things,” even money, from powerful people.

Those things remain unknown.

I conducted numerous interviews with Gaffney while researching The Strength of the Wolf, my book on the history of the FBN. One of the subjects we discussed was the O’Keefe incident and the account given by Jill Jonnes in her book, based on her having been given access to sealed Senate Exhibit 14A.

“I interviewed and hired O’Keefe when I was the supervisor in Atlanta,” Gaffney recalled. “He’d been a lieutenant in the army, and I thought he had the right stuff. Then he came up to New York and decided to become a loner, and that’s when he got into trouble. He went into a bar in Little Italy, thinking he could blend in. Well, the hoods fingered him in a second and the next thing you know, they take his gun and badge.

“By then I was the supervisor in New York, and I referred the problem to headquarters. Meanwhile O’Keefe contacted his Congressman, which he had every right to do. Siragusa was the field supervisor, so Charlie, the Congressman, and Anslinger met with O’Keefe. Anslinger asked him, ‘How could you possibly lose your gun?’ Quick as a flash, O’Keefe reaches over and snatches Charlie’s gun. Charlie’s standing there flabbergasted, and that’s that.

“O’Keefe was sent back to work, and not long after that he was found passed-out in a car. The police reported it. And when we went to investigate, we found a matchbox folded in a V shape under the seat of the car. It was the kind of thing addicts use to sniff dope, and there was heroin residue in it. So I asked for his resignation.”

Gaffney suggested that O’Keefe survived the “hot shot” he was given at Watson’s because he was a user and had built up a tolerance to the powerful drug.

Given the lack of corroborating witnesses, it is impossible to know what happened. O’Keefe rejects Gaffney’s account as ludicrous, and Gaffney rejected the account Jill Jonnes gave from Exhibit 14A. Gaffney believed that Charlie Siragusa’s protégé, Andrew Tartaglino, the author of 14A, distorted the facts as a way of discrediting his arch-rival Gaffney and the FBN, which by 1968 had become a liability to LBJ and the CIA.

It is also possible that Gaffney’s enforcement assistant at the time of the O’Keefe incident, Pat Ward, whom Tartaglino branded “the chief architect of corruption” in New York in the 1950s and early 1960s, misled Gaffney about the incident at the Watson Bar.

“Gaffney was a good district supervisor,” one former agent explained, “but he was a square, and he was duped by Pat Ward.”

Partners in Crime

Who put the heroin in Ed O’Keefe’s beer? Anyone investigating the crime would try to answer that question. The chief suspects in the case were the FBN agents who were with O’Keefe on the night of the incident and, for obvious reasons, the bartender at the Watson Bar.

In my emails to various officials in 2015, I noted that two of the agents present on the night Ed O’Keefe was given a near fatal hot shot were still alive: Joseph Stone and Henry Brentari. To no avail, I suggested that the diligent Justice Department officials interview these ancient men while they still could.

Harold Diller died in 2004, but not without leaving a legacy. In the book RFK: A Candid Biography of Robert F. Kennedy (New York: Dutton, 1998), author C. David Heymann cited Diller as claiming that Bobby Kennedy, while serving as staff attorney for the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, would accompany FBN agents while they drove around the South Bronx and Harlem.

Diller said that Kennedy would bust into apartments and make arrests with the agents. Diller told Heymann that “agents who hung out with Bobby, fellows named Jimmy Ceburi and Arthur Krueger, would purportedly come back with reports of him seizing bags of coke for his own use or, more probably, for distribution among his buddies.”

In the absence of any sworn testimony from Stone and Brentari, I tried to assemble some basic facts about them. Ed O’Keefe was helpful and indicated that they had both worked for the CIA and may have been CIA agents working undercover on the night of February 7, 1959.

Stone, according to O’Keefe, had acquired invaluable intelligence about the Aswan Dam in Egypt for the CIA. Like Diller and Brentari, Stone quit the FBN shortly after the O’Keefe incident. Stone and Diller became law partners in New York City, defending major mobsters who had been arrested on drug charges.

O’Keefe spoke to Stone in 2015, but Stone advised him to forget about the incident. “I asked Joe Stone when I met him in New York if it was Diller that did this to me,” O’Keefe explained. “He told me no, that the order came from higher up. He said, ‘Ed, you have been very successful in your life, why don’t you just forget it.’

“I told him I couldn’t do this.”

I tried to reach Stone, but he avoided me.

I did contact Henry Brentari in Connecticut and, as O’Keefe told me, he acknowledged having spent his career in the CIA. He claimed he did not recall the names Diller or O’Keefe, but he did remember Joe Stone. They were friendly after their FBN work. He did not recall Watson’s Bar. He left the FBN in 1960 or ’61. He was no help.

According to O’Keefe, half the agents in his group were CIA officers or collaborators with the CIA. This should not come as a surprise. The CIA provided job training to selected officers by running them through the FBN’s New York office. Spending six months with the FBN in NYC taught young CIA officers how to work with murderers, pimps, whores, burglars and mercenary informants, which was invaluable, given that the CIA’s principle agents often reside in a foreign nation’s criminal underworld.

A few months reading FBN files also provided budding CIA officers with biographical information on the people they might soon be working with—the world’s top traffickers and criminals. Working with the FBN introduced them to every vice imaginable and taught them how to exploit these vices in people, while committing and getting away with every known crime and scam.

They learned how to manage street-level prostitutes and international arms traffickers as informants; how to pay off corrupt cops; how to acquire and assume a false identity; and how to cross a border to deliver a stolen Renoir or explosives.

All of these lessons occurred in real life.

It is also useful to know that CIA case officers recruited lawyers and funneled them through the FBN as well. Some of these lawyers became criminal defense attorneys specializing in mob-related international drug cases. Such well-placed attorneys passed on confidential information about drug rings and drug traffickers to their CIA case officers.

Other lawyers were slipped into the Justice and Treasury Departments, as well as into state and city law enforcement offices, where they sabotaged cases against important CIA assets who sometimes happened to be international drug traffickers.

One Manhattan mob lawyer, Mario Brod, was recruited by James Angleton into the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in 1944 and, in 1947, while managing a casino in Campione, Italy, Brod “cultivated” Lucky Luciano for Angleton and the CIA. While working for Angleton he engaged in black-market activity and the “shakedown of Fascists” among other things.

According to Angleton, “the Subject made a personal profit of almost $40,000 from a venture, but OSS saw no impropriety since no U.S. Government funds were involved.”[2]

In 1948, Angleton quashed an Army investigation of Brod which may have exposed operations he had conducted for “this organization.” Brod continued to work for the CIA in New York City through the 1960s.

When Luciano, the “capo di tutti I capi” (“boss of all bosses”), was imprisoned in 1936, he entrusted his family to Vito Genovese. But Genovese was indicted for murder and fled to Italy in 1939, and the position passed to Frank Costello, a suave, smooth gangster who got Magistrate Thomas A. Aurelio a seat on the New York State Supreme Court.

Someone recorded and leaked portions of one of Costello’s phone conversations with Aurelio and, as reported in the August 29, 1943, edition of The New York Times, Aurelio was overheard pledging his “undying loyalty” to Costello.

Such was the power of mobsters in New York City.

While setting up narcotics connections between Germany, Yugoslavia and Sicily for his Mafia partners back home, Genovese befriended the secretary of Mussolini’s Fascist Party. In return for his generous contributions, Genovese was allowed to purchase a power plant near Naples and manage a chain of banks controlled by the Fascist government.

For ordering the murder of anti-Fascist Carlo Tresca in New York in 1943 (allegedly committed by Joe DiPalermo and Carmine Galante), he was awarded Italy’s highest civilian title, presented personally by Mussolini.

The happy arrangement ended in June 1944 when the Army’s Criminal Investigations Division (CID) learned that Genovese was operating on the black market while serving as a special employee of the U.S. Army. It also learned he was wanted for murder.

In November 1944, the State Department issued Genovese a passport and he was returned to New York to stand trial. But a general had become involved in the case and, in December, Genovese was transferred to a civilian prison in Bari, where Charlie Siragusa, having transferred from the FBN to the OSS during the war, questioned him.

As Siragusa recalled, “being a civilian cop I couldn’t resist pushing the hood on his New York City rackets. It was known that he still pulled the strings back there.”

The CID’s efforts to achieve justice met yet another obstacle when, in January 1945, the principal witness against Genovese died of an overdose of barbiturates while sequestered in a Brooklyn jail. Shortly after the murder of the only material witness against him, Genovese’s extradition was processed and he was escorted to New York in May 1945 where the case against him was dismissed. As Brigadier General Carter W. Clarke remarked in a memo dated June 30, 1945, the Genovese file was so “hot” that it should “be filed and no action taken.”[3]

Criminology Professor Alan Block asserts that the Genovese case “marks an important point in American political history” in which professional criminals continued to ply their trade, but “for new patrons.” No doubt these “new patrons” were America’s master spies.

Democracy fails when it is secretly ruled by a consortium of politicians, gangsters and CIA spies. And that is why a guy like Ed O’Keefe was willing to walk away from an attempt on his life without making a fuss. That is my opinion. I also believe Genovese was framed as part of an underworld reorganization initiated by the CIA.

Ed O’Keefe had his own opinion.

“It’s interesting,” O’Keefe observed, “that the Watson Bar was only a block or so from where I first lived when we moved to New York. But I had to move away because my wife told my landlady I was a narcotic agent. The neighbors weren’t entirely reputable. So it’s possible someone from this neighborhood could have seen me in the bar and put something in my beer. It’s possible, but I doubt it.

“I don’t think the heroin was put in my drink until I was making my phone call, because heroin is very fast getting into your system. They must have given me a large quantity too, because I was vomiting blood for two days.

“I’ve been told that Agent Howard Diller, my partner, didn’t come home that night,” O’Keefe continued. “I was told that his wife divorced him because of this, and I thought he could have done it.”

But at this point, it’s anyone’s guess.

Exhibits 14A, B, C and D at the 1975 Permanent Subcommittee hearing consisted of four reports authored by Andrew C. Tartaglino, then chief of inspections, and sent to John Ingersoll, the director of the BNDD. The first, dated November 21, 1968, is titled “Integrity Investigation—New York Office, History, Recommendations and Conclusions. The second, dated May 30, 1969, is titled “Integrity Investigations—Individuals Resolved Since Inception.” The third, dated June 1, 1969, is titled “Status of Investigations—June 1, 1969.” The fourth, dated June 23, 1969, is titled “Integrity Investigation—Resolved and Unresolved—June 1, 1969.” Henry Jackson quote from U.S. Senate Federal Drug Enforcement Hearings Before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee of Government Operations, 94th Congress, 1st Session, June 9, 10 and 11, 1975, Page 140. ↑

Mary Ferrell file on Brod. ↑

Alan A. Block, “European Drug Traffic and Traffickers Between the Wars: The Policy of Suppression and Its Consequences,” Journal of Social History, vol. 23, no. 2 (Winter 1989), 315-337. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Douglas Valentine is the preeminent expert on the CIA.

His books include: The Phoenix Program (1990); The CIA as Organized Crime (2017); The Strength of the Wolf (2004); The Strength of the Pack (2010); Pisces Moon (2023); and The Hotel Tacloban (1994).

Doug can be reached at dougvalentine77@gmail.com.