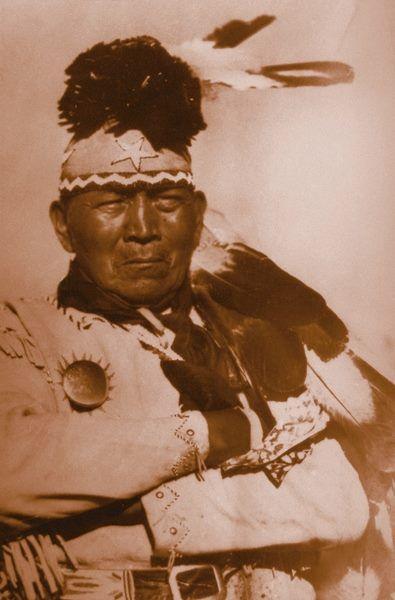

The barbarism of the North American conquest was exemplified by scalping and mutilation of Native Americans

[This article is part of a CovertAction Magazine special on Indigenous Peoples Day.—Editors]

In May, President Donald Trump announced that he would not recognize Indigenous People’s Day and would bring Columbus Day “back from the ashes.”

A few months later, War Secretary Pete Hegseth announced that 20 U.S. soldiers who took part in the massacre of hundreds of Lakota Sioux at Wounded Knee in December 1890 will keep the Medals of Honor they were awarded. Hegseth said that the soldiers “deserved those medals.”

Trump’s MAGA movement has generally aimed to glorify the founding generations of the United States and to erase public memory of the dark underside of American history.

Teachers and professors who try to teach the truth have come under attack in a growing climate of totalitarianism.

Along with slavery, the massacre of the Native-American population has by now been well documented. It has been made even more clear in a number of new historical studies that take on a subversive air under the Trump-led order.

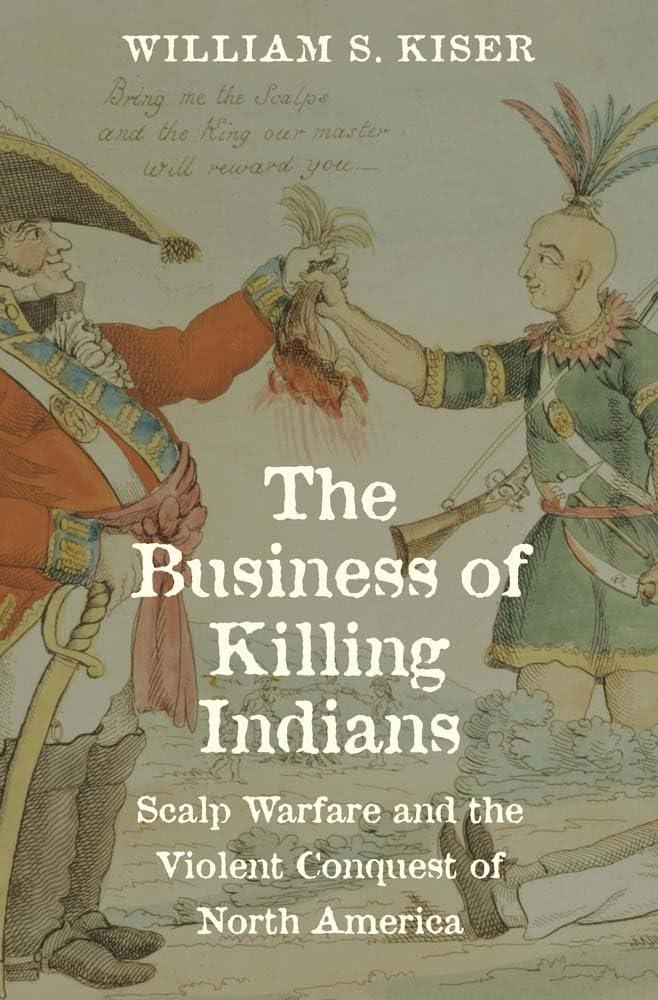

One of these studies, by William S. Kiser, Chair of the History Department at Texas A&M-San Antonio, methodically details how white soldiers serving with colonial militias and state police agencies like the Texas Rangers were paid bounties for Native-American scalps and other body parts, which they often took as trophies.

Kiser’s book was published this year in the prestigious Lamar Series in Western History with Yale University Press and is entitled The Business of Killing Indians: Scalp Warfare and the Violent Conquest of North America.

Kiser estimates—conservatively—that between ten and twenty thousand Native Americans were scalped over a 250-year period from the mid-1600s to the late 1800s.[1]

He notes that there was a performative aspect to the practice that was often accompanied by the display of Native-American body parts in town plazas, courthouses and churches as a signal of conquest.[2]

The Indian killers were valorized in local newspapers and would often decorate their belts, guns, horses or homes with scalps and other body parts.

The practice of scalping was especially cruel because the soul in many Native traditions is contained in the crown of the head, meaning that acts of scalping and beheading detached the victim’s soul from the rest of his body, dishonoring him/her in death and preventing the possibility of their renaissance in the afterworld.

According to Kiser, surviving kin suffered the psychological trauma of knowing that their loved one would experience the afterlife in soulless shame and misery.[3]

Driven by intense personal and often racialized hatred along with the possibility of material gain, scalp warfare was sponsored by local government officials who aimed to save money by paying bounties instead of having to finance regular soldiers.

The bounty hunters were usually part of irregular forces that took advantage of Native rivalries to recruit Natives to do some of their dirty work.

In 19th century Mexico, the lure of high profits led bounty hunters to initiate a killing spree of mestizos whose black hair was almost indistinguishable from Apache Indians.[4]

In 2021, a group of Penobscot filmmakers found evidence of 69 scalp proclamations in New England between 1675 and 1760. At least 375 Indians perished as a result of those laws.[5]

Hannah Duston became a celebrity in Puritan Massachusetts who later had three monuments dedicated to her after she escaped from Abenaki captivity in Haverhill in September 1694 and killed ten of her captors, scalped their corpses, and strode into Boston toting the scalps.[6]

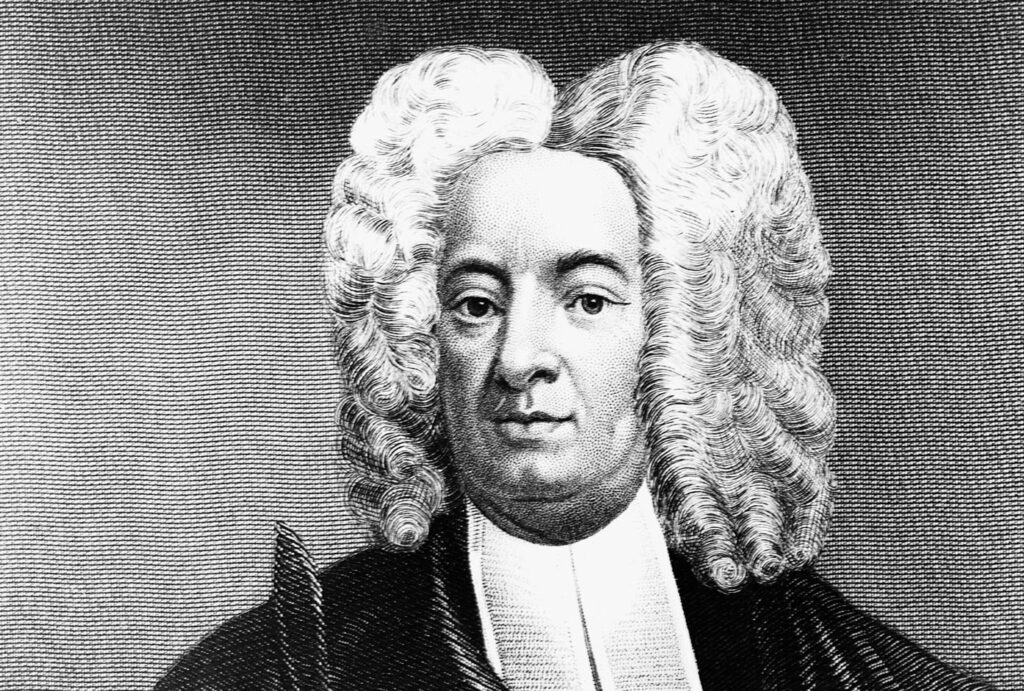

Puritan Minister Cotton Mather preached a sermon praising Duston for “cutting off the scalps of ten wretches,” crediting “God the savior” for protecting her and an accomplice “under such harrowing circumstances.”[7]

All told, Kiser determined that well over 100 different scalping laws were implemented across North America, some of which included rewards for captive women and children to be sold as slaves.[8]

One of the first scalping laws was advanced by William Kieft, the Governor of New Netherlands from 1638 to 1647 in modern-day New York in retaliation for Raritan Indian attacks on Dutch settlers. A reward of Native beads was offered for Raritan Indian heads.[9]

The earliest French bounty arose in 1688 at the onset of King William’s War when the Governor of Canada used financial incentives to convince France’s Abenaki allies to attack members of the Iroquois Five Nations who had allied with the English in Massachusetts and New York.[10]

With time, Catholic missionaries and priests became deeply involved in scalp warfare, largely by encouraging Indians to whom they had religious access to attack, kill and mutilate Indigenous enemies of the French like the Iroquois.[11]

From his palace in Versailles Louis XIV struck down the scalping edicts not out of humanitarian concern but because of the feared high cost, though New France (Quebec) Governors Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac, and Jean Bochard de Champigny defied the King’s orders.[12]

The latter considered bounty hunting invaluable because it eliminated the need for hundreds of troop salaries.[13]

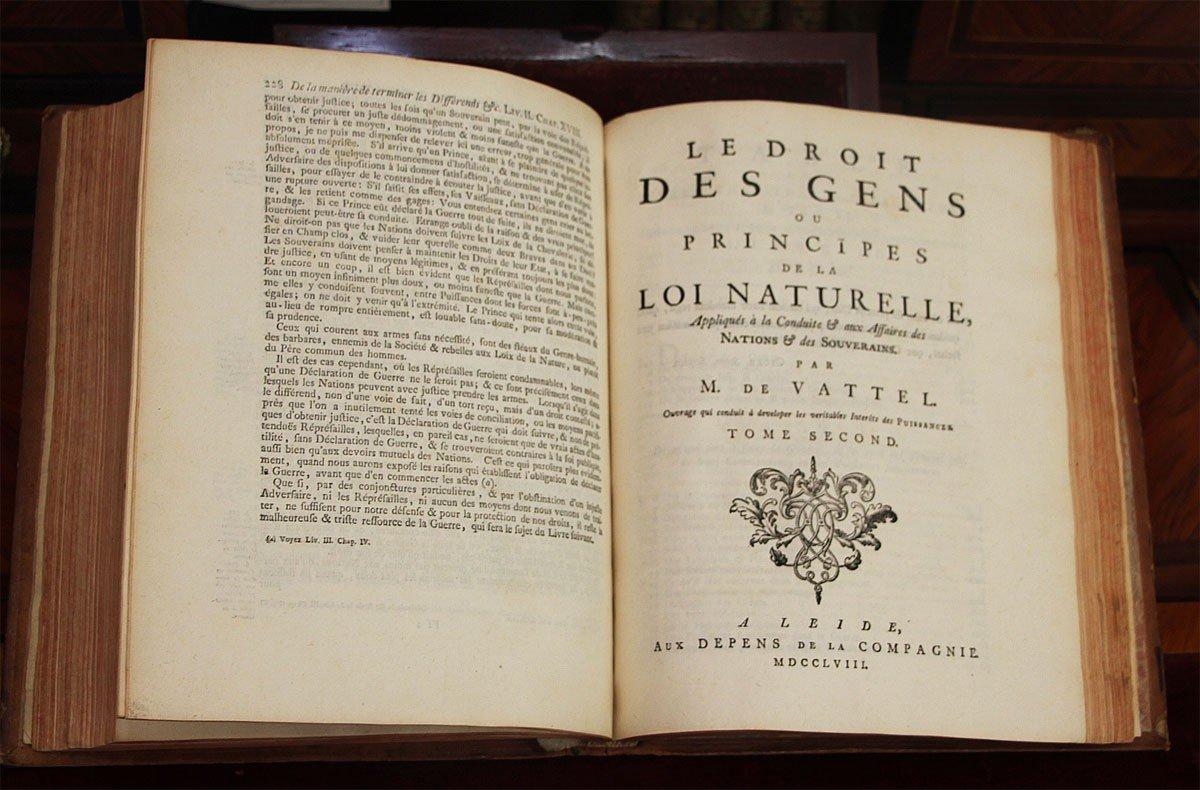

State-sponsored scalp warfare proliferated in the British colonies throughout the Revolutionary War era despite the dissemination of Emmerich de Vattel’s The Law of Nations (1758), a seminal treatise on international law influencing America’s founding generation that called for protection of non-combatants in warfare and set the precedent for 20th century human rights declarations.[14]

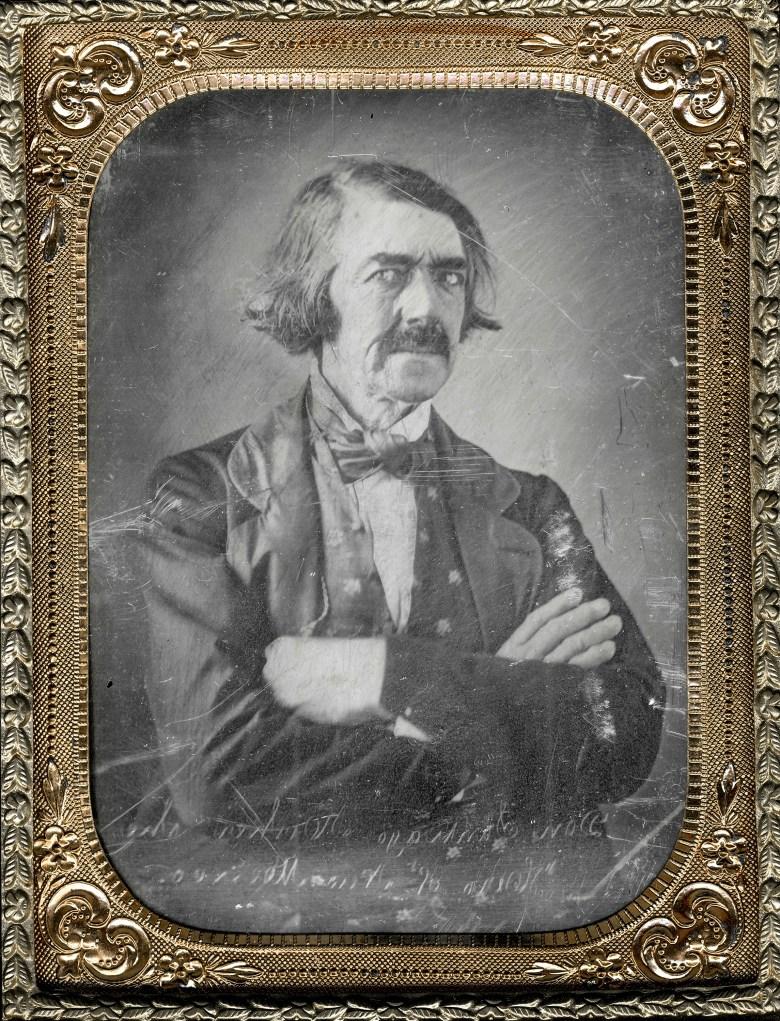

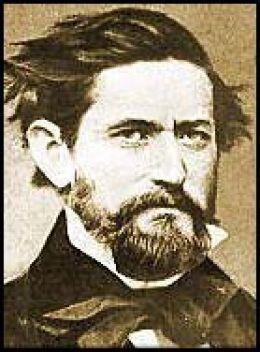

One of the most infamous scalp hunters of the 19th century was a hard-drinking Missouri gun-runner and mercenary named James Kirker, the “terror of the Apaches,” whose exploits in Indian killing would “fill a volume,” according to Kiser.[15]

On July 6, 1846, Kirker led a party of men into the town of Galeana in the Mexican province of Chihuahua that slaughtered between 130 and 170 Apaches, some of them women and children, after first getting them drunk so they would not be able to fight back.

The Mexican government hired Kirker as a mercenary because it was seeking to extract copper ore on Apache land.

Afterwards, Kirker’s soldiers were paid in gold and silver by local officials for body parts of the slain Apaches, whose remains were put up in the Galeana town cathedral.[16]

The butchery was especially bad for the Apache’s since they believed that deceased persons entered the afterlife in the same physical condition that they departed earth, meaning that “any man, woman, or child who died at the hands of Kirker’s cutthroats would live on in hairless shame.”[17]

The same was true of the Apaches who were slaughtered in the 1837 “Johnson Massacre” in modern-day New Mexico.

In that crime, Kentuckian mercenary John Johnson and his men severed 27 Apache scalps after luring Apache Chief Compa with the hope of a truce and then plying the Apaches with liquor.[18]

Asa Daklugie, a 20th century Apache chief, told a historian that “it was not in revenge for depredations made by Apaches that these men [Johnson’s band of mercenaries] killed, but for the money offered. A bounty was offered for Apache scalps and it was collected too.”[19]

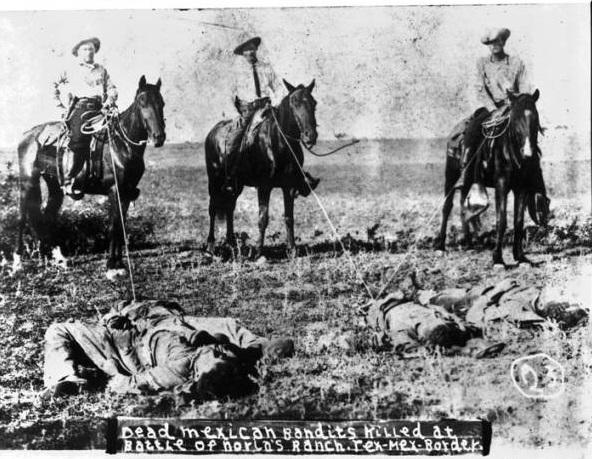

Kirker and Johnson would have fit in well with the Texas Rangers, a police-paramilitary force established after the Texas revolution whose members were paid bounties for the scalps of Apaches and Comanches whom they hunted and killed.[20]

Kiser points out that the origins of the Texas Rangers as an Indian fighting organization stemmed from anxiety over a joint 1838 Mexican-Kickapoo Indian rebellion known as the Córdova Rebellion (led by Vicente Córdova) in Nacogdoches, Texas, that was brutally suppressed.[21]

The Rangers attracted many ruffians who became heroes in a Texas culture that placed a high value on martial masculinity and frontier combat experience.[22]

Some of the more aggressive Ranger regiments supplemented their pay through bounty-hunting operations that included not only scalping but also taking of women’s breasts as trophies.[23]

One Ranger who went by the nickname “Indian hater” (Jeff Turner) became a master at taking out an Indian scalp extremely quickly, with one slash with his butcher knife, earning him comparison to a “carpenter.”[24]

When a debate broke out in Congress about the Texas Rangers, Congressman Armistead Burt (D-SC) stated that he “did not know of anywhere on this continent where the cutting of throats and blowing out of brains were indulged in with a keener relish than in that part of Texas [where the Rangers operated largely along the Mexican border].”[25]

A number of Texas Rangers continued their Indian killing exploits in California during the California Gold Rush and early years of California statehood.

Kiser writes that, instead of offering scalp bounties, the California legislature paid salaries to paramilitary operatives who pursued, captured, enslaved and murdered Indians.[26]

These operatives developed a habit of dismembering the bodies of dead Indians as an expression of racial hatred, with many of the scalps ending up on public display or as home decorations.[27]

John Coffee Hays, San Francisco’s first sheriff, had once led deadly Texas Ranger operations against the Comanches and Apaches and campaigns below the Mexican border. In his new job, he organized private volunteers to police California’s frontier that killed yet more Indians.[28]

The state legal system’s role in sanctioning scalp warfare was epitomized in the appointment of judges and other elected officials who had themselves engaged in the practice.

Much like in Texas, Indian killers were heralded as heroes in local newspapers, although the Daily Alta California condemned the taking of child Indian captives, which it compared with chattel slavery in the southern Confederacy.[29]

In 1855, members of an Oregon militia murdered and mutilated Walla Walla Chief Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox, whose ears were cut off and taken along with his scalp by his killers as a souvenir.

Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox’s killing sparked the so-called Walla Walla war that lasted for the next three years and inflicted deep spiritual wounds on the chief’s surviving family and followers.[30]

Walter S. Jarboe’s Eel River Rangers committed some of the worst atrocities directed against Northern California’s Yuki Indian population, whom Jarboe characterized as “the most degraded, filthy, miserable stinking set of anything living that come under the head of and rank as human beings.”[31]

A native Kentuckian, Jarboe had developed a reputation for brutality during the U.S.-Mexican War, which future President Ulysses S. Grant called among the “most unjust wars in history.”

As a pretext for the massacres, which were approved by California Governor John B. Weller, Jarboe and others claimed that the Yuki Indians had been killing white settlers’ livestock for years. Eyewitnesses insisted, however, that almost every account of Yuki wrongdoing had been either totally fabricated or egregiously exaggerated in order to justify deadly operations.[32]

The latter has a familiar ring to it for more contemporary U.S. military operations, which have also been based on fraudulent pretexts and fake or exaggerated atrocity stories.[33]

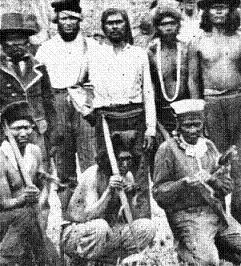

The gruesome history of atrocities and genocide against Native Americans is often taught in isolation in U.S. history courses; however, it should be presented to students as setting the groundwork for the present day.

Once the Native population was pacified, then U.S. irregular warfare methods were applied against people of color around the world who stood atop natural resources that U.S.-based corporations and the U.S. state itself coveted.

Though the practice of bounty hunting and scalping may have receded, U.S. soldiers are still prone to carry out body mutilations and take trophies of enemies they have killed.

The practice was widely adopted in the Pacific and Vietnam Wars and has been reported in Afghanistan and Iraq.

William S. Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians: Scalp Warfare and the Violent Conquest of North America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2025), 17. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 7. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 25, 26. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 17. ↑

New England had the most scalp laws of any British colony in North America. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 55, 56. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 56. John Lovewell was a prolific Indian scalper and killer who was celebrated in local lore with Duston. In retaliation for the gruesome acts that he had committed, the Abenaki killed him and then mutilated his corpse, showing how extra-lethal violence could cut both ways. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 17. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 23. Kieft’s policy was criticized by a member of his advisory council, David De Vries, who said that “no profit was to be derived from a war with savages.” De Vries feared correctly that the scalp bounty policy would exacerbate rather than mitigate inter-ethnic violence and racial hatred. Other administrators for the West India Company, which Kieft had worked for, called the scalp-bounty practice “unnatural, barbaric, unnecessary, unjust and disgraceful.” The British crown also condemned the practice as “barbaric.” ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 26. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 23. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 27. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 33. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 87. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 94. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 94, 95. The Mexican government had issued bounties of “100 pesos for the scalp of an Apache man, 50 for a woman’s and 25 pesos for a child’s scalp.” Kirker had a road named after him in Concord, California, though the name had to be changed after a retired San Francisco area social worker and master’s student at Arizona State University, Daniel Kelly, found out that Kirker was a “homicidal maniac.” ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 96. In the Apache ethos, desecrations of the dead demanded that the living seek retribution. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 102, 103. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 104. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, ch. 4. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 144. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 147. ↑

Idem. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 161. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 159. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 179. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 180. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 183. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 187, 188. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 196. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 201. ↑

Kiser, The Business of Killing Indians, 202. A special committee of the California state legislature did disprove of Jarboe’s conduct, though Jarboe’s supporters blocked the committee from reading its report before the legislature. ↑

See A. B. Abrams, Atrocity Fabrication and Its Consequences: How Fake News Shapes World Order (Atlanta: Clarity, 2023). ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.