The large-scale operation in Rio de Janeiro carried out on October 28, which has already left at least 121 people dead and once again laid bare the logic of war applied to poverty, should not be understood solely as a local public-security issue.

It is part of a global control system that has the United States as its central architect and Brazilian political elites at both the federal and state levels as its key executors and beneficiaries.

The operation, officially named Operação Contenção (“Operation Containment”), was launched by state authorities on the basis of 100 arrest warrants targeting alleged members of the Comando Vermelho—one of Brazil’s oldest and most powerful criminal organizations, which emerged in Rio de Janeiro’s prison system in the late 1970s and today controls drug-trafficking networks in multiple regions of the country.

The raid took place in the Complexo da Penha, a large favela cluster in Rio de Janeiro with more than 130,000 residents, an area historically marked by state neglect and recurring episodes of militarized policing. According to police, only 20 of the 100 targeted suspects were arrested.

Yet the operation left 121 people dead, raising serious concerns about its scale, proportionality, and the lethal use of force against a densely populated civilian community.

Throughout the 20th century, the United States projected drug control as a fundamental instrument of its international power.

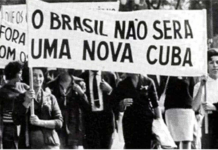

The discourse of “combating drug trafficking,” which intensified after Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs” in the 1970s, served to consolidate spheres of influence, justify military interventions, especially in Latin America, and support a diplomacy grounded in the idea that hemispheric security depends on controlling specific psychoactive substances, notably cocaine and marijuana, as well as the bodies that produce and transport them.

In practice, the country exported a drug-policy model that combines militarization, selective punishment, and economic interests.

In Brazil, this model was well-received because it encountered fertile ground in a society marked by state violence, repression of poor communities, and structural racism, legacies of a colonial and slave-based past.

In this context, drug repression became a technology for managing poverty and exercising racial control. At the same time, it has served as a political tool, fueling electoral campaigns centered on promises of “order,” and as a business mechanism, securing police budgets and contracts with private security firms. Explicit and implicit connections to the hemispheric center of power in Washington enable these dynamics.

A striking example of this process can be seen in recent actions by Donald Trump in the Caribbean, which revived the rhetoric of “narcoterrorism” and gave particular force to what occurred in Rio de Janeiro.

Under the pretext of combating trafficking, the United States has intensified military operations in the region, sending troops, ships and aircraft to intercept “suspect” vessels, many of which were sunk in what can only be described as extrajudicial executions.

At the same time, the Trump administration has openly accused the governments of Colombia and Venezuela of being “narco-states,” regimes complicit with or directly benefiting from drug-trafficking networks.

In Brazil, this rhetoric has quickly gained traction among national and state elites, who have adapted it to their own political agendas. In line with this trend, the Rio de Janeiro state government signed a direct cooperation agreement with the U.S. Diplomatic Security Service to “confront the Comando Vermelho,” and even sent reports to the DEA claiming that the group had operational branches in the United States.

In Congress, Bill 1283/2025, authored by far-right members of Congress, Danilo Forte (União), and reported by Nikolas Ferreira (PL), seeks to classify both the Comando Vermelho and the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) as terrorist organizations.

The PCC, which emerged in São Paulo’s prison system in the 1990s and has since grown into one of the largest and most sophisticated criminal networks in South America, controls drug-trafficking routes across Brazil and maintains connections to regional and transnational criminal markets.

This proposal would align Brazilian domestic policy with U.S. counterterrorism doctrine, potentially opening the door to expanded military cooperation and even direct foreign intervention. The governor of Rio de Janeiro, Cláudio Castro (PL), submitted a report to the U.S. government requesting that the Comando Vermelho be designated a “narco-terrorist” organization.

This securitized framing has also influenced public opinion: Recent polling shows that 72% of Rio de Janeiro residents support labeling these groups as “narco-terrorists,” underscoring how fear and insecurity can mobilize support for punitive measures even when their practical effectiveness remains unclear.

It is worth noting that Brazil’s two major criminal organizations were born inside the prison system as a reaction to massacres carried out by the State.

This convergence of discourse and institutions is accompanied by an uncomfortable material reality: the steady flow of U.S.-manufactured firearms fueling Brazil’s internal wars.

A Rio de Janeiro Military Police study released in May 2025 revealed that more than 45% of all rifles seized in the state originated from U.S. manufacturers with export licenses and entered the country clandestinely through routes passing through Paraguay, Bolivia and Colombia.

In the end, the same country that supplies the weapons and the war model positions itself as a partner in fighting the violence it helps sustain.

The Lula administration, for its part, has attempted to balance narratives. On the one hand, it publicly reaffirms national sovereignty and criticizes U.S. interference in South America. On the other hand, it feels compelled to demonstrate practical alignment with the anti-narcotics agenda.

This serves both to avoid losing political ground to the far right and its “the only good criminal is a dead criminal” rhetoric, and to show that Brazil can conduct its own “war on crime.” This ambiguity is typical of unequal power relations in international politics, where a peripheral state reproduces hegemonic security discourse while rhetorically asserting independence.

In practice, the Rio–U.S. connection expresses a historical project in which political elites at the core and the periphery of the hemispheric system use drug control as a tool of power, turning Rio into both a showcase and a testing ground for the militarized and market-driven logic of the contemporary “war on drugs.”

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Priscila Villela is a professor of International Relations at PUC-SP and deputy coordinator of both the Center for Studies on Drugs and International Relations (NEDRI) and the Center for Transnational Security Studies (NETS).

Priscila Villela is a professor of International Relations at PUC-SP and deputy coordinator of both the Center for Studies on Drugs and International Relations (NEDRI) and the Center for Transnational Security Studies (NETS).

Priscila can be reached at pvillela@pucsp.br.

Paulo J. R. Pereira is an associate professor of International Relations at PUC-SP, a researcher at INCT-INEU, and the coordinator of the Center for Studies on Drugs and International Relations (NEDRI).

Paulo can be reached at pjreispereira@gmail.com.

Donald Trump’s basic problem is that he thinks that Republicans cannot turn away from him and that his collusion with Al Qaeda will not cost him his freedom at the end of his term.