[This is one of three articles we are running this week on the 1-year anniversary of the so-called Syrian “revolution.”—Editors]

U.S. media accounts of the fall of the Assad dynasty in Syria failed to disclose that the U.S. had engaged in a thirteen-year-long operation that started with the Arab Spring and continued with the launching of Operation Timber Sycamore by the Obama administration, the largest covert operation since the CIA’s support for the Afghan mujahadin in the 1980s.

The New York Times, Wall Street Journal and even alternative media outlets like Democracy Now, made it seem like Assad had fallen suddenly and organically, as a result of a popular rebellion and that this was cause for celebration.[1]

Blogger Caitlin Johnstone wrote “we’re all meant to pretend this was a 100 percent organic uprising driven solely and exclusively by the people of Syria despite years and years of evidence to the contrary” and the fact that the “U.S. power alliance [encompassing Israel, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar] crushed Syria using proxy warfare, starvation sanctions, constant bombing operations, and a military occupation explicitly designed to cut Syria off from oil and wheat in order to prevent its reconstruction after the Western-backed civil war.”[2]

Johnstone is on the mark but even she may not be aware of the fact that the regime-change operation targeting Assad fit with a long history of U.S. covert meddling in Syria dating back to the 1940s.

In 1999, historian Douglas Little published an article in Middle East Journal entitled “Cold War and Covert Action: The United States and Syria, 1945-1958,” which noted that, “as early as 1949, Syria had become an important staging ground for the CIA’s earliest experiments in covert action.”[3]

The experiment included the staging of a coup d’état in March 1949 against Syrian President Shukri al-Quwatli by right-wing military officers led by Husni al-Zaim, who had been jailed at the end of World War II for receiving illegal funds from France’s pro-Nazi Vichy regime.[4]

A member of a secret anti-Ottoman-empire organization who had opposed a U.S. mandate in Syria at the end of World War I, al-Quwatli had forged very good relations with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, wanted to sustain close ties with the U.S. and had reached out to the U.S. for financial support.[5]

The main impetus for the coup–the CIA’s first covert regime change operation—was the goal of establishing an oil pipeline built by the Arabian-American Oil Company (ARAMCO) carrying Persian Gulf oil from the Dhahran oil fields in Saudi Arabia through Syria to the Mediterranean.

Europe’s economic recovery depended on oil, and the ARAMCO Trans-Arabian pipeline would have helped provide it with cheap oil from the Middle East.

Little is highly critical of the covert operation to oust al-Quwatli because he says that it “helped reverse a century of friendship [between the U.S. and Syria] that began with the American missionaries who flocked to the Levant after 1820 and encouraged the Arabs to overthrow the Ottoman yoke.”

Al-Quwatli put himself in the crosshairs of the CIA because he had refused to grant concessions to ARAMCO and go forward with negotiations for the Trans-Arabian pipeline, which was to be built by the San Francisco-based Bechtel Corporation.[6]

Al-Quwatli was also unwilling to crack down on Syria’s left-wing movements and Communist Party, which had become more and more influential.

CIA operatives Miles Copeland, Jr., and Stephen Meade were dispatched to Syria to engineer the March 1949 coup.

Described by historian Hugh Wilford as a “tough-looking, muscular, James Bond kind of character,” Meade met secretly at least six times with Colonel Zaim to discuss the possibility of an army-supported dictatorship that would replace Quwatli.[7]

In the days leading up to the coup, Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, George McGehee, a wealthy oilman from Waco Texas visited Damascus and is alleged to have sanctioned the coup plot.[8]

According to Little, U.S. officials recognized that Zaim was a “banana republic dictator type” who “did not have the competence of a French Corporal.” They supported him because of his “strong anti-Soviet attitude, willingness to talk peace with Israel [which the Truman administration chose to support] and his desire for American military assistance.”

The Soviet newspaper Pravda reported that Zaim’s coup had been organized “by the Anglo-Americans rivals for the oil resources and strategic bases in that area.”[9]

A 1950 article in the Middle East Journal emphasized Zaim’s use of Circassian and Kurdish units to carry out the coup, foreshadowing the importance of the Kurds and other minority groups in 21st century regime change operations.[10]

Just before he took power, Zaim had requested that U.S. agents “provoke and abet internal disturbances, which are essential for coup d’état or that U.S. funds be given for this purpose as soon as possible.”

Stephen Meade reported on April 15, after Zaim had taken power and Quwatli had been placed under arrest, that “over 400 Commies [in] all parts of Syria have been arrested” and that Zaim was “prepared to ratify TAPLINE [ARAMCO oil pipeline].”

A month later, Zaim formally approved a long-delayed TAPLINE concession, removing the final obstacle to ARAMCO’s plan to pipe Saudi oil to the Mediterranean. Zaid also broadened his anti-Soviet campaign by formally banning the Communist Party and jailing dozens more left-wing dissidents.[11]

British journalist Patrick Seale wrote that Zaim’s “regime lay somewhere between political gangsterism and musical comedy.”[12]

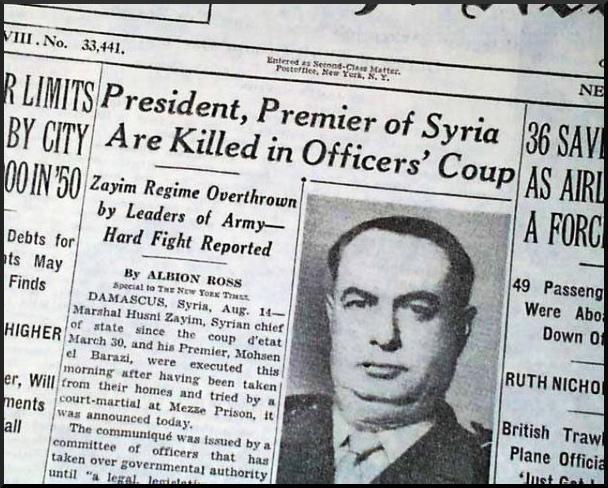

On August 2, Zaim was overthrown and executed after a coup by Colonel Sami al-Hinnawi and other army officers who were unhappy with Zaim’s personalistic rule and friendly policies toward Israel (which had defeated Syria in the 1948 Israeli independence war).

The Truman administration recognized the new government; however, U.S. military intelligence warned that “commies were attempting to assume increasing influence in the new parliament by offering to support numerous non-commie candidates throughout the country.”

When Hinnawi’s party announced plans for a Syrian union with Iraq’s Hashemite dynasty, he was ousted in Syria’s third coup in nine months. The coup was led by Colonel Adib Shishakli, who was very close with Miles Copeland.

Copeland and others in the U.S. embassy in Syria were aware of Shishakli’s coup plans in advance and gave the green light.

Scuttling plans for a Syria-Iraqi federation, Shishakli renewed the TAPLINE concession on terms favorable to ARAMCO and expressed willingness to conclude a peace treaty with Israel. At the same time, he dissolved parliament and set up a military dictatorship.

His brutality was evident when he deployed aircraft and tanks to help crush a Druze rebellion in Jabal al Arab, resulting in the death of around 200 civilians.[13]

The Eisenhower administration wanted Syria to join the Baghdad Pact, a pro-Western alliance modeled after NATO that would help isolate radical Arab states like Egypt under Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Colonel Adnan al-Malki was a main opponent of the Baghdad Pact within the Syrian military. He was assassinated by a right-wing group supportive of Shishakli, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), that had long been rumored to have been close to the CIA.[14]

In August 1955, after al-Quwatli won an election, CIA Director Allen Dulles flew to London with Kermit Roosevelt—architect of the CIA’s 1953 coup in Iran—to work out details for another Syrian coup with Britain’s secret intelligence service (SIS).

Dulles’s plan (Operation Straggle) called for Turkey to stage border incidents, for British operatives to stir up Syria’s desert tribes, and for American agents to mobilize SSNP guerrillas, all of which would trigger a pro-Western coup that would bring Shishakli back into power.[15]

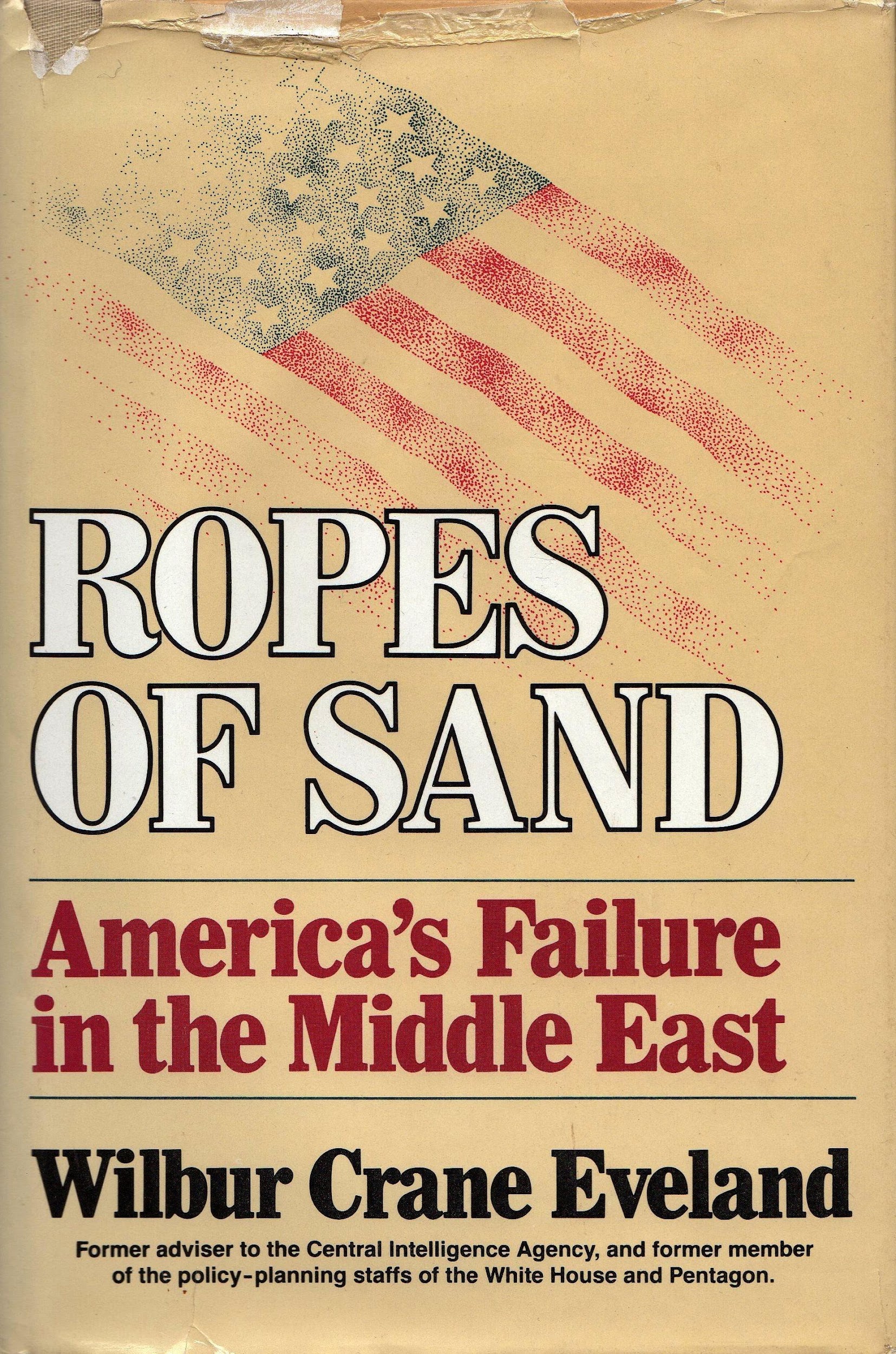

In his 1980 memoir Ropes of Sand: America’s Failure in the Middle East, CIA operative Wilbur Crane Eveland wrote about payoffs to a conservative politician, Michail Ilyan, and about CIA operative Art Close’s almost comical efforts to smuggle Shishakli’s chief of security, Colonel Ibrahim Husseini, who was as big as a moose, in the trunk of an embassy car back into Syria from across the border (Husseini had been serving as Syrian military attaché in Rome). Eveland describes his assignment in Syria as being “to stem the [country’s] leftist drift.”[16]

The key CIA point man in the coup plot, Archibald Roosevelt, Kermit’s brother and Theodore Roosevelt’s grandson, possessed a deep hatred of communism synonymous with his class background and went on to organize Armenians, Kurds, Georgians and other minority groups in Turkey to penetrate the Soviet Union.[17]

Another key CIA operative was Howard Stone, a political action specialist who coordinated Syrian dissidents in Tehran and Khartoum. A veteran with Kermit Roosevelt of Operation Ajax in Iran, Stone was expelled from Syria after Syria’s chief of counterintelligence, Abdul Hamid al-Sarraj, got wind of the coup plot.[18]

According to Eveland, the coup plotters walked into Serraj’s office, turned in their money, and named the CIA officers who had paid them. They then went on television to announce that they had received money from “the corrupt and sinister Americans in an attempt to overthrow the legitimate government of Syria.”[19]

Miles Copeland’s Account

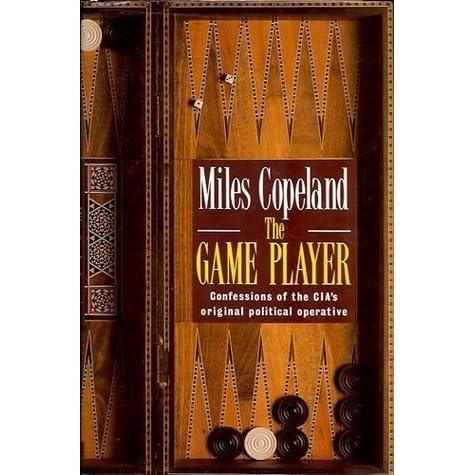

Miles Copeland, Jr., revealed U.S. coup plotting in Syria in his 1989 memoir, The Game Player: Confessions of the CIA’s original political operative.[20]

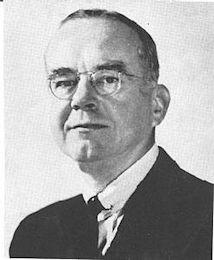

Described by Archie Roosevelt as a “brilliant, talented extrovert from Alabama [Montgomery],”[21] Copeland was married to a British intelligence asset, Elizabeth Lorraine Adie[22], and was influenced by the ideas of James Burnham, an original neo-conservative and proponent of aggressive rollback operations.

Writing numerous articles for the conservative National Review, in 1986 he gave an interview to Rolling Stone in which he stated: “Unlike The New York Times, Victor Marchetti and Philip Agee, my complaint has been that the CIA isn’t overthrowing enough anti-American governments or assassinating enough anti-American leaders, but I guess I’m getting old.”

Working as a military attaché at the U.S. embassy, Copeland recounts in The Game Player his arrival in Damascus in 1949 and development with a British MI6 man of “all sorts of projects that combined the best in American money and British brains.”

These projects included obtaining secret documents from the Syrian Defense Ministry after Copeland bribed two male secretaries and got them to steal documents from their employer’s safe.

Once it was decided that Zaim—whom he referred to as a “burly Kurd”—was the man to lead the coup against al-Quwatli, Copeland says that he helped arrange for him to come to Damascus to serve as chief of police before making him commander-in-chief of the Syrian army.

Though at times downplaying the U.S. role in the 1949 coup, Copeland elsewhere suggests, in a slip of the tongue, that he and Steve Meade masterminded it.

Before the coup took place, Meade took a ride with Zaim in a limousine through Damascus and pointed out targets to be seized during the coup, including the city’s main radio station, power generators, and the central office of the telephone company.

Further, Copeland and Meade assisted Zaim to develop a program of disinformation, and drafted a statement that he gave to the Syrian people after the coup was consummated.

Copeland seems most proud about a devious scheme he concocted to trick one of al-Quwatli’s allies in the army, Fakhri al-Barudi, into raiding his home in order to make it look like Syria had become a police state.[23]

When Copeland ordered an Air Force pilot named Dick Rule to confront Barudi’s men, Rule tellingly replied: “Screw you. You go out there yourself cowboy. I’m not going to get my ass shot off in aid of one of your CIA pranks.”[24]

Copeland was so close with Adib Shishakli that he gave his second son the middle name Adib—after Adib Shishakli had assisted his pregnant wife before she went into labor.

Copeland characterized Adib as a “likeable rogue” who drank too much, smoked pot, made false accusations and had committed “blasphemy, murder, adultery and theft.”

Copeland admitted to buying Shishakli’s loyalty through blackmail, having gained information about his “dabbling in homosexuality” during a stint in prison.

Believing that Shishakli was smarter than Zaim, he felt that he would manipulate him once the new government was installed. After Zaim came to power, Copeland wrote that the coup increasingly became Shishakli’s.

Later, when Shishakli mounted a failed coup, he had to flee Syria after being given a death sentence and went to Paris where Copeland visited him and paid his hotel bill.

Déjà Vu?

At the end of the chapter on Syria in The Game Player, Copeland suggests that the 1949 Syrian coup was studied at CIA training classes for the next two decades.

This is ironic since, in the 2010s, the CIA mounted one of its largest covert operations in Syria since the anti-Soviet mujahadin in the 1980s—Operation Timber Sycamore.

The target of Timber Sycamore, Bashar al-Assad, bears some resemblance to Shukri al-Quwatli in that he refused to construct the Trans-Arabian pipeline through Syria, instead endorsing a Russian approved “Islamic” pipeline running from Iran’s side of the gas field through Syria and to ports in Lebanon.

According to Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., the Islamic pipeline would make “Shiite Iran, not Sunni Qatar, the principal supplier to the European energy market” and “dramatically increase Iran’s influence in the Middle East and world”—which Miles Copeland’s heirs would never allow.[25]

Copeland interestingly drew the lesson from the 1949 coup that Middle Eastern societies such as Syria were inherently prone to “chronic political instability” and “self-destructive emotionalism;” therefore the next time the U.S. set about the “busienss of interference in the internal affairs of sovereign nations,” it would “need to find a stronger leader than Zaim,” one capable “of building a durable power base and fo surviving.” In other words, the problem was “not one of bringing about a change of government, but of making the change stick.”[26]

While it is unclear if they hold much historical consciousness, today’s regime change operators seem to think in a similar kind of way as Copeland. Their hubris makes it likely in turn that history will repeat itself—all indicators suggest that the U.S. imposed Islamic regime that overthrew Assad is as brutal and unpopular as Zaim was in 1949 and hence may not stick for very long. A sign of this is the protests being mounted by Shia Alawites subjected to persecution and their launching a general strike, which may soon grow into a larger-scale rebellion.

See, e.g., Neil MacFarquhar, “The Assad Family’s Legacy Is One of Savage Oppression,” The New York Times, December 8, 2024, and flawed coverage in Democracy Now. ↑

Caitlin Johnstone, “Syria is Absorbed Into the Empire,” Consortium News, December 9, 2024, https://consortiumnews.com/2024/12/09/syria-is-absorbed-into-the-empire/ ↑

Douglas Little “Cold War and Covert Action: The U.S. and Syria, 1945-1958,” Middle East Journal, 44, 1 (Winter 1990), 51-75. ↑

Patrick Seale, The Struggle For Syria: A Study of Postwar Arab Politics, 1945-1958 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965), 43. ↑

J.K. Gani, The Role of Ideology in Syrian-U.S. Relations: Conflict and Cooperation (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2014), 31, 34. Among other things, al-Quwatli had requested that the U.S. provide police equipment and training to enable his government to maintain internal order. ↑

Part of al-Quwatli’s concern with TAPLINE was that it would upset the Iraqi Petroleum Company (IPC) and the British who had held Syria to obtain independence, more so than the U.S. He also feared that Syrian public opinion would reject TAPLINE on its territory, seeing it as a new form of indirect economic control. Sami Moubayed, Syria and the USA: Washington’s Relation with Damascus From Wilson to Eisenhower (London: I/B. Tauris, 2012), 74. ↑

Hugh Wilford, America’s Great Game: The CIA’s Secret Arabists and the Shaping of the Modern Middle East (New York: Basic Books, 2013), 99. A veteran of the elite U.S. Army Rangers Battalion ( “Darby’s Raiders”) in North Africa during World War II, Meade had also served with the Office of Strategic Service (OSS) undertaking escape and evasion operations in Iran while disguised as a Kurdish tribesman and accompanied Archie Roosevelt on a mission to rescue some American missionaries who had been kidnapped by a fleeing a German SS platoon. ↑

McGehee had a background in naval air intelligence and served under General Curtis LeMay, architect of the Tokyo firebombing in World War II. In the Kennedy administration, McGehee served as Under Secretary for political Affairs. After his retirement, he was appointed to the board of Mobil oil company. ↑

Andrew Rathmell, Secret War in the Middle East: The Covert Struggle For Syria, 1949-1961 (London: I.B. Tauris, 1995), 30. ↑

Alfred Carleton, “The Syrian Coup D’états of 1949,” Middle East Journal, 4, 1 (January 1950), 7. Zaim was described by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as a “convicted swindler” and by historian Sami Moubayed as a “military officer who looked and acted like Benito Mussolini.” He developed close Syrian relations with its former colonial master, France, which became his primary arms supplier. ↑

Additionally, Zaim withdrew all Syrian claims against Turkey (a staunch U.S. ally) and signed an armistice with Israel. ↑

Seale, The Struggle For Syria, 118. ↑

See Al Jazeera’s documentary, “Al Shishakli: Syria’s Master of Coups.” Shishakli’s political mentor, Anton Sadeh, was described by The New York Times as a “fascist oriented leader.” The party to which both belonged adopted Nazi-type salutes. Written up in local newspapers for his exploits fighting the French in Syria’s anti-colonial war, Shishakli had also been considered one of the heroes of the 1948 Palestine War, praised for his role in helping to take Samakh City and attacking Israeli positions on the Daughters of Jacob Bridge. ↑

Malki became a national hero. A statue of him was put up in Damascus and he was a great influence on Hafez al-Assad. ↑

Journalist Tim Weiner reported that the CIA delivered a total of half a million Syrian pounds to leaders of the coup plot. See Tim Weiner, Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA (New York: Doubleday, 2007), 138. ↑

Wilbur Crane Eveland, Ropes of Sand: America’s Failure in the Middle East (New York: W.W. Norton, 1980), 253, 254. ↑

Wilford, America’s Great Game, 45. Archie Roosevelt knew Arabic and Hebrew and had supported Arab nationalists who opposed European colonialism. Wilford noted that the roots of Roosevelt’s anticommunism dated to his school days. When he came across The Daily Worker in the Groton (Massachusetts prep school) library, he said he “found its message of class hatred a calumny on the ideals of America.” At the end of World War II, Roosevelt feared that Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin was intent on reestablishing the old Tsarist empire and pushing for domination of the “Straits of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles, and a warm water port on the Persian Gulf.” ↑

Weiner, Legacy of Ashes, 139. U.S. Ambassador to Syria Charles Yost called the CIA plot “clumsy.” In addition to his posting in Iran and Sudan, Stone, who was born in Cincinnati and lost much of his hearing after being exposed to too many explosives during his military training in World War II, served with the CIA in Pakistan, Vietnam and Nepal. He was also chief of operations of the CIA’s Soviet bloc division from 1968 to 1971. ↑

Eveland, Ropes of Sand, 254; Weiner, Legacy of Ashes, 139. ↑

Miles Copeland, The Game Player: Confessions of the CIA’s original political operative (London: Aurum Press, 1989). ↑

Wilford, America’s Great Game, 65, 67, 68, 69. The son of a physician, Copeland was a skilled jazz musician and varsity boxer at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa in the late 1930s who became ensconced in the world of espionage and subversion while serving with the U.S. Army Counter-intelligence Corps (CIC) in World War II. ↑

David McGowan, Weird Scenes Inside the Canyon: Laurel Canyon, Covert Ops & The Dark Heart of the Hippie Dream (Headpress, 2003), 278. ↑

Copeland tricked Barudi by having a Syrian intelligence agent he had paid off provide him with misinformation suggesting that Copeland had key secret documents in his home and would be away during the weekend of the raid. Copeland had made it look like he was leaving for the weekend but hid out in his house so he was ready to expose and confront the raiders to make them look bad. ↑

Copeland, The Game Player, 96. ↑

Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., “Why the Arabs Don’t Want Us in Syria,” Politico Magazine, February 22, 2016, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/02/rfk-jr-why-arabs-dont-trust-america-213601/ ↑

Quoted in Wilford, America’s Great Game, 128, 129. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

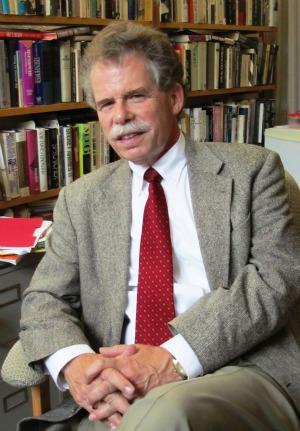

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.