Honduras held national elections on November 30. At stake were the office of president, 125 seats in the National Congress, and more than 280 mayoral and municipal governments. Three major political parties, including the two traditional National and Liberal parties, and the more recently formed LIBRE Party, ran presidential candidates.

By Tuesday, December 9, there was still no official final announcement of the presidential winner. Therein lies a tale.

What happens in Honduras is important to the United States. Honduras has been the platform for the projection of U.S. military and political power throughout Central America.

The CIA coup that deposed the Árbenz government in Guatemala in 1954 was staged from Honduras, as was the Contra War against Nicaragua in the 1980s. In the past few decades, Honduras has been one of the largest sources of emigration to the United States.

U.S. and Canadian mining and other extractive industries have had heavy investments in Honduras and are deeply implicated in the displacement of local communities and environmental degradation there. Honduras has suffered as a major source of drug traffic into the U.S.

In 2021, the previous Honduran president, Juan Orlando Hernández, was extradited to the United States on charges that he presided over the trafficking of at least 400 tons of cocaine into the U.S. He was convicted and sentenced to 45 years in prison. But President Donald J. Trump gave Hernández a full pardon on November 29, one day before the Honduran election.

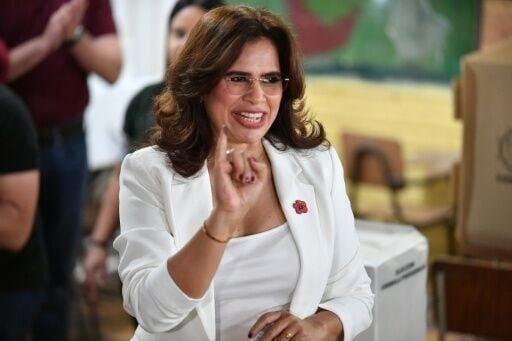

Xiomara Castro’s Accomplishments and Dilemmas

The current (outgoing) government headed by Xiomara Castro and the LIBRE Party has been in power since January 2022, and has made some important advances in undoing the corruption, violations of human rights, and impunity of the Hernández government.

Under Hernández and his National Party, basic social services, public health, education and much else were neglected, abandoned or privatized.

Under Xiomara Castro, new schools are being built, hospitals and the dilapidated public health system improved, and the government has taken measures to address the rights and safety of women in a country that has had one of the highest rates of femicide in the hemisphere.

The Castro government has also tried to defend the country’s sovereignty, pursuing a more independent foreign policy not dictated by the United States, and annulling laws that enabled the establishment of model cities—autonomous enclaves run by foreign interests—in Honduras.

But Castro’s LIBRE government has faced daunting challenges. It does not control many of the country’s municipal and departmental governments. An extensive network of corruption and drug culture has had more than a decade to root itself deeply, with the protection of Castro’s predecessor, Juan Orlando Hernández.

That network, which remains mostly intact, includes a large portion of the national police and the military, the very security forces that Castro has had to depend upon to curb the network of corruption.

When she sent the security forces into several cities where gangs were particularly violent, she was cheered by some and criticized by other Hondurans who saw the security forces as a big part of the problem.

Castro and her LIBRE Party government needed the income from foreign extractive industries, the same industries whose unchecked exploitation of resources and forcible displacement of communities she had pledged to challenge and control.

Throughout Xiomara Castro’s four years in office, the U.S. Embassy in Tegucigalpa continued to issue slightly veiled warnings that she had better keep Honduras open for (foreign corporate) business.

In recent months, under pressure from the Trump administration, Honduras accepted several thousand Hondurans deported from the U.S. by the administration over the past year.

Welcoming people back home might seem like a positive move, but it has had at least two negative effects on Castro’s government. First, it lowered the amount of remittances sent back to the country from Hondurans, remittances that in recent years have accounted for at least 20% of the country’s income.

Accepting back deportees also caused criticism and concern among some Hondurans that Castro and LIBRE were not standing up to Trump, and were failing to protect Hondurans in the U.S.

Castro’s own family has links to powerful interests, a situation that some Hondurans believe has further compromised her ability to move more decisively in controlling corruption and extractive industry excesses.

Castro’s government has also faced severe challenges in its attempts to stop the development of model cities on Honduran soil. Model cities are enclaves of foreign investment and control that are free to operate outside of the laws of the host country, and are considered virtually sovereign entities.

Their managers can ignore the rules and environmental restraints that bind the rest of Honduras, and can displace or pressure local populations, while claiming that they will provide jobs for local people. Under Hernández’s National Party government, at least one model city, Próspera, was initiated.

After Xiomara Castro came to power in early 2022, the Honduran Congress canceled the law enabling model cities in Honduras. Many Hondurans hailed this as a step toward regaining national sovereignty and protecting people and environment.

But there was powerful pushback. Wealthy right-wing associates of President Trump—including Peter Thiel and Eric Prince, the head of Blackwater—were among the major interests in Próspera and other model cities projects.

In a blog in November of last year entitled, “How President Trump Can Crush Socialism and Save a Free City [Próspera] in Honduras,” close Trump adviser Roger Stone wrote, “Trump has quite a bit of leverage at his disposal to upend [Xiomara] Castro’s fledgling regime. Honduras could be liberated and Castro’s regime upended without firing a single shot or deploying a single troop.”

Castro also moved to curb additional foreign extractive projects that had done much to displace communities and cause environmental harm. Her government announced that Honduras was withdrawing from the Investor State Dispute Settlement system (ISDS) under which foreign investors can sue governments for losses and estimated future lost profits over decisions they believe affect their interests. Currently, Honduras faces at least $US 14 billion in claims from foreign corporations, equivalent to roughly 40% of the country’s annual budget.

Despite the improvements her government has been able to make, some Hondurans have expressed criticism, coming both from supporters who wanted her to succeed and from opponents who wanted to paint as negative a picture as possible so as to discredit Castro and LIBRE’s entire effort to reform the corruption and the rampant extraction of resources that has benefitted the wealthy and foreign corporate interests. LIBRE’s candidate for president in the current election, Rixi Moncada, was seen as very likely to continue and, perhaps, even widen those reform efforts.

Recent Honduran Elections

The history of recent Honduran elections does not provide much relief from disillusionment and concern.

In June 2009, President Manuel (Mel) Zelaya—Xiomara Castro’s husband—was forcibly deposed in a coup orchestrated by senior members of the National Party and backed by the United States.

Elections in November of that year took place amid huge street protests and legal denunciations of the coup, and heavy-handed military and police repression.

That election, controlled by those who had staged the June coup, proclaimed National Party candidate Pepe Lobo the winner, but that was widely seen as illegitimate because it was run by the coup plotters and took place amid widespread popular protest and repression.

In the election of 2013, Juan Orlando Hernández, one of the 2009 coup leaders, was the presidential candidate of the National Party. Out of the massive protests and resistance to the coup, a new political party, LIBRE, was formed, with Xiomara Castro as its presidential candidate. The electoral process, voting and ballot counting, and the announcement of the winner were marred by allegations of fraud. International observer missions criticized the process.

When Hernández was declared the winner, many cried fraud. Hernández presided over a vast expansion of narcotics trafficking, corruption and repression. The Honduran murder and femicide rates rose to among the highest in the world during those years.

In 2017, Hernández ran for re-election with the National Party, despite the Honduran Constitution’s prohibition against re-election. The Supreme Constitutional Court, controlled by Hernández supporters, declared that the prohibition deprived Hernández of his “right” to engage in political expression. A coalition of popular organizations, labor unions and human rights groups opposing Hernández’s possible re-election called itself the Convergencia contra el Continuismo (Convergence against Continuance).

For that election, popular media figure Salvador Nasralla and his supporters organized a political party they called Salvador de Honduras, a play on the Spanish word for savior—Nasralla was the savior of Honduras! He portrayed himself as the anti-corruption candidate. In order to put up a united front against Hernández and the National Party, LIBRE joined with Salvador de Honduras in declaring Nasralla their presidential candidate.

Once again, the election was marred by irregularities, including accusations that the military that was charged with securing the ballots for counting had tampered with them. (The military was under the control of Hernández.)

On the night of the election, Nasralla gained a lead that a member of the Supreme Electoral Council said was unsurmountable. Shortly thereafter, the count was stopped and no reports were issued, allegedly because of problems with technology. When the count resumed, Hernández had a slim lead and was soon declared the winner. Again, massive protests and condemnation of electoral fraud followed.

It is important to note that, despite some mild initial criticism of the electoral process, the United States accepted the official results and regarded Hernández as the legitimate Honduran president in the elections of both 2013 and 2017, just as the U.S. had accepted the 2009 coup. The coup plotters and their National Party government kept Honduras “open for business,” and accepted the extensive U.S. military presence and the corruption.

Hernández was Washington’s man, and had been warmly welcomed many times at the White House by both Republican and Democratic presidents. But his narco-dictatorship had become an increasing embarrassment to Washington, and the 2021 defeat of his National Party sealed his fate. The Biden administration requested his extradition to the U.S. to stand charges for drug trafficking to the U.S. Xiomara Castro’s government complied. Hernández was convicted and sentenced to 45 years in a U.S. prison.

The 2021 Election

I was in Honduras for the weeks before, during and after the 2021 election. This time, Xiomara Castro was the LIBRE Party candidate with Nasralla as her vice-presidential running mate. In the weeks before the election, the usual uncertainties about the vote-counting technology and other problems were aired and finally settled to the satisfaction of the parties and international observers.

Hernández did not dare run again for a third term, Instead, the National Party ran the mayor of Tegucigalpa, Nasry Asfura, who could be relied upon to continue the extractive narco-state of the previous 12 years.

For days before the election in the city of El Progreso, I observed long lines of people waiting outside banks for the bonus being handed out to those who registered to vote. The bonuses were handed out by Hernández’s National Party, while National Party operatives in rural communities handed out cash bonuses or promised modern appliances to peasants if they promised to vote for Asfura. After the election, some people said they accepted the “gifts” but did not vote for Asfura.

On election night, I listened to the returns on Radio Progreso. No one knew for sure what would happen, given past electoral fiascos. I thought it would be a long night of counting and waiting. But the result was clear before 10:00 p.m. Xiomara Castro was elected by a large majority. When the radio announced the news, huge and raucous celebrations broke out in neighborhoods of El Progreso and other cities.

This victory was historic in several ways. Castro was the first woman elected president in the history of the country. The LIBRE Party’s victory broke the century-old stranglehold of the two traditional parties—National and Liberal—that had maintained an elite monopoly on political power.

Context of the 2025 Election

Weeks before the 2025 election, Honduran Attorney General Joel Zelaya announced that the Public Prosecutor’s office had obtained audio recordings of conversations among the head of the National Party caucus, a member of the Honduran military, and Cossette López, the National Party member on the National Electoral Council (CNE) discussing detailed plans to disrupt the November 30 election. López is quoted saying, “What is important is that Salvador Nasralla be announced as the winner, not Rixi Moncada.”

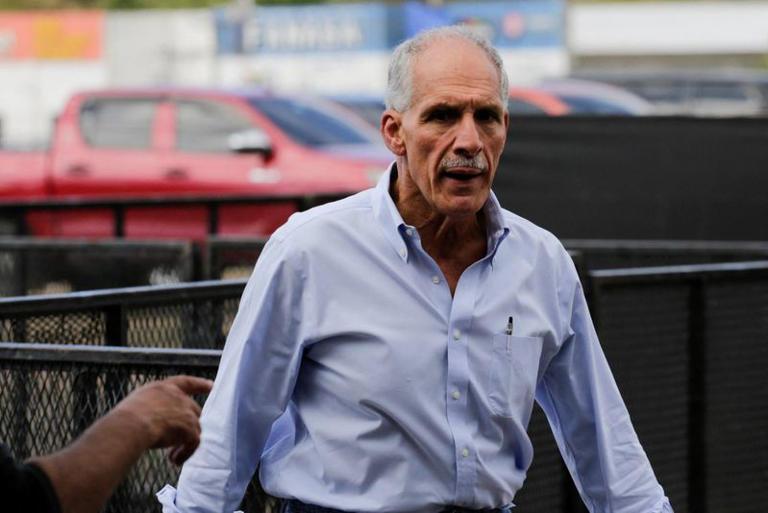

Nasralla had defected from Castro’s government to become the presidential candidate of the Liberal Party—a move that some saw as unprincipled opportunism.

There were other concerns going into the 2025 election. Assassinations of candidates at the local municipal level occurred. Such pre-election violence is not new in Honduras but it is always a destabilizing element. There were reports of threats against the local officials whose job was to oversee and count the votes in communities across the country.

Concerns and warnings were raised about the reliability and efficiency of the technical systems used to record, count and transmit the totals of votes, and about the private company whose technology was to be used.

Hondurans with relatives in the U.S. were sent messages essentially warning that if they voted the wrong way, the U.S. government would stop their relatives from sending remittances.

For months, Castro’s government was the target of a negative news campaign that emphasized her “failures” while ignoring her successes, failing to add any context that might provide nuance and understanding of the complexities of the Honduran political situation.

This discrediting campaign was meant to appeal to both Hondurans who were disillusioned with the slow progress of change, and to weaken LIBRE candidate Moncada who is seen as likely to continue Castro’s reform efforts, possibly with more success. The negative news was also meant to weaken international solidarity for LIBRE and progressive politics in Honduras.

In at least one (unconfirmed) report, some Evangelicals in the United States, including also the Association for a More Just Society, encouraged and organized protest demonstrations in at least one U.S. city, demanding that Honduran authorities ensure a fair and clean election, placing the burden on the Xiomara Castro government rather than the right-wing interests that seem to be doing everything in their power to disrupt the election.

Such false “impartiality” was designed to confuse and weaken progressive solidarity in the U.S. with progressive or reformist government in Honduras.

The audio conversations released by Castro’s Attorney General revealed an attempt to ensure that only delegations of international election observers friendly to the traditional National and Liberal parties be admitted, and that delegations that seem to promise actual impartiality be interfered with.

There was at least one report, from CNE member Marlon Ochoa, that a pre-election briefing for a delegation was interrupted by opposition party operatives. The impartiality of election observers was thrown into question.

Shortly before election day, President Trump wrote on social media his strong endorsement of National Party candidate Nasry Asfura, and promised more aid to Honduras if Asfura won, but dire consequences if Asfura lost. Many saw this as a brazen interference in the Honduran election.

Then the day before the election Trump pardoned and released former Honduran President Juan Orland Hernández from U.S. imprisonment. Hernández remains a powerful figure in the National Party and far-right economic and drug interests, including members of the Honduran security forces.

It was no coincidence that there was an ongoing effort to have the U.S. Congress continue military aid to Honduras and to drop pending legislation (such as the Berta Cáceres Human Rights in Honduras Act) that demands an end to U.S. military aid. Representative Maria Elvira Salazar (R-FL) introduced HR 4202 into the U.S. House of Representatives to demand just that.

Conveniently, continued military presence would provide a threat of U.S. intervention in case the election results do not favor the U.S. In the context of recent history, it also signals the Honduran military and the political opposition that the U.S. would back them should they decide to intervene directly in the electoral process or its outcome. The Honduran military have a long and close relationship to the U.S. military, and the country has had a large U.S. military presence since at least 1980.

The rapid and large U.S. military buildup in the Caribbean that Trump has overseen over the months before the election was ostensibly aimed at Venezuela, but it also provided added ammunition for Liberal Party candidate Nasralla who, in the days before the election, warned Hondurans that a vote for LIBRE and Moncada would invite direct U.S. military intervention.

There were also warnings that LIBRE and Moncada would invite Venezuelan influence in Honduras and the “Venezuelanization” of Honduras. This parallels the warning circulated before the 2017 election if LIBRE won that election, it would preside over the “Nicaraguanization” of Honduras.

Election Fiasco

On Sunday, November 30, Hondurans voted. There was no early announcement of a winner. The TREP automatic vote count system showed a small early lead for Asfura, but the automatic count was slow.

Mid-day on Monday, the automatic count was stopped. The National Electoral Council said there were technical problems. At that point, Asfura was ahead of Nasralla by less than half a percent, with Moncada trailing badly. The website on which official results were posted also had problems, adding to popular frustration.

The counting continued manually and very slowly. On Tuesday, President Trump claimed the Honduran authorities were trying to change the results of the election. He warned “there will be hell to pay.” [presumably, if Asfura were not declared winner].

On Wednesday, December 3, with almost 80% of the vote counted, Nasralla had taken a small lead over Asfura. The difference between the two was less than 20,000 votes out of an estimated five million.

Because of the closeness of the count and the delays, election observers from the Organization of American States and the European Union called for calm and patience. They did not report any concerns about the legitimacy of the process. By Thursday night, there was still no announced winner.

On Thursday night, Marlon Ochoa, the LIBRE member of the National Electoral Council, held a press conference in which he laid out eight points of fraud and irregularities that, he said, had occurred in the process.

These included irregularities and apparent fraud in the ways in which vote counts were transmitted from polling places across the country to the central count and the CNE and problems with the TREP automatic count technology that were known well before the election but never fully addressed. He also listed other irregularities.

Most damning, Ochoa laid out evidence that the two traditional parties—National and Liberal—had colluded in various ways to prevent Moncada and LIBRE from winning. He also described efforts to prevent or interfere with truly impartial international observer delegations from functioning.

He faulted the OAS and EU delegations and others for painting the election as peaceful and normal, and failing to report apparent irregularities. He mentioned widespread attempts to prevent people from voting.

On the basis of such accumulated evidence, Ochoa called for the election to be annulled. By Saturday, December 6, LIBRE’s lawyer, Edson Argueta Palma, had submitted a formal request to the CNE that the election be annulled.

On Monday, December 8, the national emergency agency (Sistema Nacional de Emergéncia) reported that, during and shortly after the November 30 election, its hotline had received thousands of calls from frustrated voters complaining about intimidation from criminal elements that prevented them from voting.

Over the next few days, these reports were corroborated and amplified by a variety of sources, including residents of neighborhoods controlled by criminal gangs, human rights organizations, and others. Many accused the powerful criminal gang MS-13 of threatening to kill family members of anyone who was known to have voted for LIBRE. MS-13 was also accused of threatening election observers.

As of this writing on December 12, the situation remains without resolution and Honduras is without a new president. If history repeats, it is likely that many congressional and local government elections will also be questioned, and the final composition of the new Congress may not be known for some time.

What Does It Mean?

At this time, it is uncertain whether the election will be annulled. The Honduran Constitution seems to provide that, in the event of an electoral annulment, the current sitting government (Xiomara Castro and LIBRE) continues in power for two years until a new election can be held.

In fact, very little can be predicted with certainty about what will happen in Honduras in the next few weeks and months. Will the Honduran military intervene, as they have before in the country’s history? Will Trump make good on his threats? What will that mean? Will former President Juan Orlando Hernández return to Honduras as the charismatic leader of the far-right and the narco-traffickers? If he does, will he be arrested and tried in Honduras, as government officials have warned.

Before the November 30 election, Ismael Moreno (Padre Melo)—Jesuit priest, former director of Radio Progreso, and one of the country’s leading human rights voices—said that, no matter what happens, the Honduran people must revive the powerful popular mobilization that provided Hondurans with a strong voice in the years after the 2009 coup and the Hernández “dictatorship.”

Moreno urged that the people must take back the political institutions of the country from the narrow control of the three major parties, a control that has led to the current electoral disaster that serves only the very few and foreign interests at the expense of disenfranchising the great majority of Hondurans.

Stay tuned and prepare for a bumpy ride!

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

James Phillips is a cultural and political anthropologist with forty years as a student of Central America.

His major concerns are movements of social change, political conflict, human rights, colonialism, and immigrant and refugee populations.

He is the author of articles and book chapters on Honduras and Nicaragua. His most recent book is Extracting Honduras: Resource Exploitation, Displacement, and Forced Migration (Lexington Books, 2022).

James can be reached at anthrodocjp@gmail.com.