An on-the-ground account challenging Western propaganda

Upon landing in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (commonly known as Xinjiang), it is evident that the Uyghurs, a Turkic-speaking Muslim minority, call this home.

As I exited the airport arrivals hall, I noticed a restaurant sign reading “EGG BOMB.” The moniker cleverly implies that Xinjiang would rather be renowned for its “food bombs” than for the explosive devices employed by the terrorists who formerly tormented the region and the rest of China.

In contrast to the U.S.’s so-called worldwide War on Terror, which has claimed countless victims among innocent civilians, the Chinese government’s strict counterterrorism measures have been the subject of massive criticism in Western media, including accusations of physical and cultural genocide. Uyghur terrorism, which once posed a real threat in Xinjiang and beyond—as documented by headlines from the Associated Press—has been almost entirely erased from Western discussions, leaving a one-sided narrative that ignores the region’s serious security challenges.

While Western media reports had painted a grim picture, my on-the-ground experience told a different story.

My journey started on the city’s modern transit system, where all signage was presented in Uyghur, Mandarin and English. At one stop, three young Uyghur women boarded and sat across from me, their curious glances and cheerful conversation a testament to the normal, everyday life that continues here. When I asked to take their photo, they responded not with suspicion, but with bright, agreeing smiles.

The Grand Mosque Encounter

At Urumqi’s Grand Mosque, which can hold about 700 worshippers, I met a large Uyghur family. One younger member eagerly practiced her English, translating questions from her family: Where are you from? Do you like Urumqi? The warm conversation reminded me of similar encounters I have had around the world.

Out of respect, I did not film worshippers, but I explored and filmed the mosque’s interior when it was empty.

A Joyful Wedding Moment

While exploring, I came across a Uyghur couple, radiant in exquisite traditional dress, preparing for their wedding portraits. The bride was beaming, but the groom wore a look of profound seriousness. On a playful impulse, I gestured to lighten the mood—and to my delight, it worked! His stern expression melted into a genuine, hearty laugh. The photographer shot me a grateful smile, and what might have been a formal picture transformed into a capture of pure, authentic joy.

Xinjiang Travel by Train: How Investment and Cultural Preservation Support Minority Life

Traveling solo through Xinjiang, my main modes of transport were cars and trains. I heard station announcements in both Mandarin and Uyghur (listen here) which, while challenging for me to understand, were clearly designed to serve the region’s main ethnic groups.

China’s language policy mirrors its broader approach to minorities: Banknotes feature five scripts—Mandarin, Uyghur (Arabic), Mongolian, Tibetan and Zhuang; in Xinjiang, schools teach primarily in Mandarin—the national language and the mother tongue of 91% of Chinese citizens—but Uyghur is also included in the curriculum, just as Tibetan is in Tibet; street and shop signs are typically bilingual.

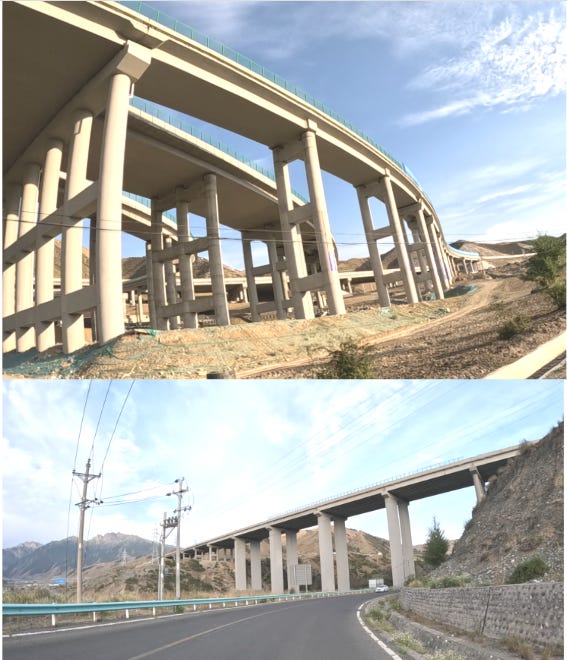

From the train window, I could see the massive investment in modern infrastructure: desert wind farms, power plants, highways, massive bridges and a vast electrical grid—all aimed at lifting millions out of poverty.

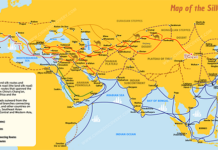

For centuries, Xinjiang stood at the crossroads of the Silk Road, its oases and mountain passes linking East Asia with Central Asia and beyond. Caravans crossing the Taklamakan Desert and the Tianshan mountains carried not only goods but also religions, languages and artistic traditions, leaving a lasting cultural imprint on the region.

Today, Xinjiang’s geography continues to give it a pivotal role. Bordering eight countries, it serves as a key hub of the Belt and Road Initiative, where new railways and highways trace routes that echo the old caravan trails, once more connecting China with the wider world.

On one trip, I sat next to a Uyghur couple. Their Mandarin was limited, as that of many other Uyghurs, and my translation app did not support Uyghur, yet we communicated through smiles, gestures and even a few photos together.

As I mentioned earlier, traveling by train here often felt like a true adventure. Announcements came only in Mandarin and Uyghur, with no English in sight. Yet fellow passengers were unfailingly kind—always eager to help, even if communication relied solely on gestures and smiles.

Heavenly Lake: Xinjiang’s Natural Wonder

Xinjiang is a land of extremes—vast deserts give way to rugged mountain ranges.

During long car rides, the air conditioning strained against the relentless heat, which often soared past 44.5°C (112°F). Yet, as we climbed into the mountains, the temperatures plunged, offering a refreshing escape.

But the true marvel awaits high in the mountains: Heavenly Lake. The name says it all. Here, deep blue waters mirror towering, snow-dusted peaks. Waterfalls tumble into serene valleys—a scene so stunning, it feels almost mythical.

Legend says dragons once swam these waters. Gazing into their depths, it is not hard to believe.

The shores were alive with visitors—Han Chinese and Uyghur Chinese families alike. I was even stopped by a few Uyghur tourists who asked to take photos with me, a lone Western face. For a moment, I felt woven into the landscape—not just a visitor, but part of the moment.

A single post cannot capture it all—I will soon share a video on my channel to do justice to this incredible place.

Disclaimer – My trip through Xinjiang was entirely independent: no government requirements, restrictions or notifications and every expense paid out of my own pocket.

Everyday Youth Culture and Uyghur Cuisine

I was captivated by the vibrant energy of the young people here—chatting animatedly in Uyghur, sharing jokes and laughter, and sometimes even turning mundane roadblocks into playful climbing structures. Their style was a modern fusion, drawing effortlessly from both global and Chinese fashion trends.

This contemporary spirit was beautifully contrasted one evening when a young woman served me a meal of delicious Uyghur food, lovingly prepared by her mother. Sampling these authentic home-cooked dishes became an instant highlight of my journey. While the daughter moved with the confidence of a global citizen, both she and her mother wore traditional Muslim headscarves—a graceful nod to heritage that spoke volumes about their pride and cultural continuity.

This blend of tradition and modernity was everywhere. I met a Uyghur shop owner whose business savvy matched her cultural pride: She was selling a beautiful array of fashionable headscarves, weaving tradition into the fabric of contemporary daily life.

Other shops, like the one below, greeted me with the vibrant sound of Uyghur music spilling into the street. It was an irresistible invitation to step inside. [Listen to it here.]

Xinjiang’s Agricultural Abundance: Farms, Markets and Local Pride

Xinjiang is often called China’s breadbasket—and a journey across the region makes it easy to see why. Golden fields of wheat and sunflowers stretch to the horizon, vineyards produce acclaimed wines, orchards yield nuts and fruits; its melons are celebrated as the sweetest in the world. The land overflows with abundance.

This fertility rests on a centuries-old relationship with water. Ingenious Karez systems—gravity-fed underground canals—channeled snowmelt from the Tianshan Mountains into the desert. Dug by hand and linked through tunnels and wells, they carried water downhill for kilometers, delivering it directly to fields without pumps or evaporation loss.

That legacy continues, though on an epic new scale. Today, modern canals and vast irrigation projects stretch across the arid lands, turning once-barren earth into seas of cotton and tomatoes. It is a story of transformation: lush, green fields flourishing in stark contrast to the desert, all sustained by mountain water.

Agriculture here is transforming rapidly. Cotton, once picked by hand, is now harvested by towering machines. Factories processing local produce create stable, better-paying jobs, while new apartment blocks and industrial plants rise as symbols of progress under Xinjiang’s vast sky.

Yet amid this modernization, the human spirit remains at the heart of the harvest. Farmers take evident pride in their work. One Uyghur melon grower even placed his portrait on the packaging—a bold signature of quality and identity, carrying his name and face from field to table across China.

At a Uyghur-run fruit shop, I marveled at watermelons so massive they seemed like boulders—some weighing up to 20 kilos (44 pounds). Struggling to lift one, I drew laughter from the shopkeeper, whose joy matched the generosity of his produce. That simple exchange perfectly captured the spirit of Xinjiang’s harvest.

Elsewhere in China, I have sipped cappuccinos made by robots, as I showed in my video China’s Collapse—or the Future Already Here? But in Xinjiang, coffee is a ritual. Cups are buried in hot sand to brew slowly, releasing the coffee’s characteristic aroma and richness. Strong, smooth and poured with care, it is more than a drink—it is a centuries-old expression of Uyghur hospitality, rooted in desert life.

Watching it being made, inhaling the aroma, and savoring that first sip was a small, yet unforgettable, moment—a taste of culture that makes travel vividly memorable.

Life in the Countryside: Kazakh and Uyghur Communities

A warm, outgoing Kazakh woman living in a wooden house amid a community of Uyghur yurts provided one of my most memorable encounters. Though I have forgotten her given name, she went by Miao on WeChat. A graduate of Xinjiang University, she was fluent in English and shared stories of her family’s deep roots in the region. As we chatted, her mother—carrying on a tradition inherited from generations of her family—welcomed us with tea and local snacks, while Miao translated her mother’s Kazakh into English for me.

Miao was the very embodiment of Xinjiang’s cultural harmony. Her life is a symphony of languages: Kazakh at home, effortless Uyghur with neighbors, and fluent Mandarin beyond. I witnessed this seamless blend culminate in a spontaneous dance with her Uyghur neighbors. Though clearly an authentic moment of their own joy and not a performance for me, they kindly let me film it. I am thrilled to share this genuine expression of communal life here.

Final Thoughts: Xinjiang Beyond the Headlines

Throughout my journey, I met many beaming Uyghurs, sometimes, I suspect, sparked by the sight of a rare Western visitor like me. What stayed with me the most was observing minority communities—Uyghur, Kazakh, and others—embracing a sense of pride, joy and contentment. This stands in stark contrast to the treatment of minorities elsewhere.

For instance, in Ukraine, the state has enacted policies that severely curtail the rights of its Russian-speaking minority: Their language has been largely banned, their political parties prohibited, their media suppressed, and their church dismantled with its assets appropriated.

Conversely, in Xinjiang, Uyghur culture is not suppressed but is instead actively preserved and supported within the framework of national law and development. It is therefore notable that many Western politicians, activists and media outlets, who frequently level baseless accusations of “genocide” in Xinjiang, remain conspicuously silent regarding the real cultural genocide faced by the Russian minority in Ukraine.

This selective outrage only underscores the importance of seeing beyond biased narratives. My travels around the globe have not always revealed the same spirit of harmony I witnessed here, making my time in Xinjiang feel even more special, uplifting and unforgettable.

▪ ▪ ▪

A further glimpse into the author’s photo album

Urumqi is a busy provincial capital that, like its counterparts across China, has achieved remarkable economic growth in recent decades. This progress brings the common challenge of traffic congestion, prompting solutions such as new bus routes and metro lines currently in planning or construction.

In Urumqi, most people pay for their subway tickets electronically with their phones, but cash is still accepted. For foreign visitors, navigating the system is easy: The ticket machine shows information not only in Uyghur, as seen here, and Mandarin, but also in English, making the city just a little more welcoming to those passing through.

The metro itself is poised for transformation. The current single line will soon be joined by Line 2, with Line 3 already under active planning and an ambitious vision for a 10-line network by 2030. Standing on the platform today, it is easy to imagine a near future where Urumqi’s public transit weaves a larger, faster, and more connected urban fabric.

Xinjiang’s landscape is being reshaped by new bridges, tunnels and roads. This expansive infrastructure is more than concrete and steel—it forms a strategic network designed to boost the economy, improve connectivity, and solidify Xinjiang’s role in the Belt and Road Initiative. It is a monumental effort to overcome geographic isolation, integrate the region with the wider world, and promote greater prosperity for all its citizens under China’s “shared prosperity” policy.

It is not Döner Kebab, it is the Uyghur original: Çağür Kebab (چاغۇر كاۋاپ). This is the Uyghur version of rotating grilled meat. The name literally means “rotating kebab.” Unlike the sandwich-style Döner, Çağür Kebab is almost always served on a plate.

The two friendly Uyghur men pictured above operate a mobile Çağür Kebab shop from a cleverly converted motorbike.

I watched as Uyghur farmers worked the same fertile oases their ancestors did, but now with the tools of today. They are the reason the scents of melons, grapes and apricots still define the air along the old Silk Road.

The bottles on the left in the photo below contain Kelimazi, a fizzy, fermented grain drink that helps locals beat the summer heat. This sweet-and-sour refreshment is a liquid taste of Silk Road tradition.

From sun-drenched vineyards and ancient orchards comes Xinjiang’s iconic snack mix: plump, sugary raisins, giant tangy apricots, and rich walnuts, all mingling with crunchy almonds and jewel-like berries. It is the timeless, energy-rich fuel of nomads and modern foodies alike—a sweet and savory taste of history you can hold in your palm.

Today, Xinjiang may be better known internationally for its cotton and tomatoes, but its reputation for grapes is both deeply historical and culturally significant. The region’s continental climate—with long, hot, sunny days, cool nights, minimal rainfall, and well-drained sandy soils—creates ideal conditions for grape cultivation, producing fruit with high sugar content, rich flavor, and intense aroma. Grapes have been grown along the Silk Road in Xinjiang for more than 2,000 years.

Western winemakers, brace yourselves: Xinjiang wines are coming. Your only hope? Convince your governments to invent a “forced labor” tale fast enough to keep the bottles off your shelves. Who knew the battle for fine wine could be so…geopolitical?

The sunflower’s value goes far deeper than its beauty. It is a versatile crop providing cooking oil, snacks, animal feed, and even biofuel. Furthermore, it benefits the environment by detoxifying soil and supporting pollinators. Given Xinjiang’s perfect growing conditions—abundant sunlight and significant daily temperature variations—it is the ideal region for these vast, golden fields.

The Uyghurs have a strong drumming tradition, with the drum called “dap” being the most culturally significant drum due to its integral role in the revered Muqam. Other drums like the naghra and dohl add to the rich percussive landscape of Uyghur music, which is a vital expression of their cultural identity.

“Muqam” is not a person. It is the name given to the grand, classical musical tradition of the Uyghur people. Think of it as a vast and sophisticated system of music, often compared to Persian Dastgah, Azerbaijani Mugham, or Indian Raga. It is the cornerstone of Uyghur culture and one of the most significant musical traditions in all of Central Asia.

The sight of mostly older Uyghur women in headscarves is a striking reminder of the profound social changes unfolding in Xinjiang. What may seem ordinary at first glance carries layers of meaning: a natural generational shift toward modern fashion; official discouragement of religious symbols such as headscarves and beards—linked to past radicalism and ongoing concerns, as Uyghur militants who helped overthrow a secular government in Syria have threatened to return to China and carry out acts of terror; and the quiet, strategic choices of younger Uyghurs to blend in for greater opportunity. From this single detail emerges a sense of evolving identity, adaptation in motion, and a broader cultural transformation shaping daily life in the region, even as the Uyghur language and much of the culture continue to endure.

The traditional Uyghur dress, exemplified below, is adorned during festivals and significant celebrations. This elegant attire, often a long, loose-fitting robe or a flowing one-piece dress, is traditionally worn over trousers. Its most striking feature is the meticulously embroidered neckline, which may be a stand-up or open collar. Worn during important events such as Nowruz (Persian New Year), weddings and religious holidays, the grandeur of the dress mirrors the profound joy and cultural importance of the occasion.

The Bank of China in Urumqi proudly displays its name in Uyghur, Mandarin and English, a small but unmistakable gesture of inclusion and cultural recognition. Switzerland does something similar, accommodating minority languages in schools, government and public spaces. Ukraine, by contrast, has gone in the opposite direction: Signage is allowed only in Ukrainian and English, while Russian—the language of millions—is explicitly banned.

Yet many of the loudest critics of China’s “cultural genocide” in Xinjiang are completely unmoved by Ukraine’s massive restrictions. Inclusion is noble in one place, exclusion forgivable in another—apparently, cultural genocide is just a matter of political convenience. And, of course, the sprawling Western anti-China ecosystem—NGOs, activists, academics, journalists—must endlessly feed its machinery with fresh accusations and scandals. Predictable, if you ask me.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Felix Abt is the author of “A Capitalist in North Korea: My Seven Years in the Hermit Kingdom” and of “A Land of Prison Camps, Starving Slaves and Nuclear Bombs?”

He can be reached via his Twitter account.

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/3/29/tibet-dying-a-slow-death-under-chinese-rule-says-exiled-leader

China is taking journalists from many countries, including Turkey, to East Turkestan and having them engage in propaganda.

Eleven journalists from Turkey also went and wrote articles in favor of China.

“Robin” — bot, troll, or wannabe “activist” — drops a link from the Times of Israel, of all places. The headline is already dripping with propaganda: “nonviolent Tibetan leaders grapple with Chinese occupation.” A neat trick — spotlight someone else’s occupation while whitewashing Israel’s own, and the ongoing holocaust it commits.

https://www.timesofisrael.com/in-dharamshala-nonviolent-tibetan-leaders-grapple-with-chinese-occupation-gaza-war/