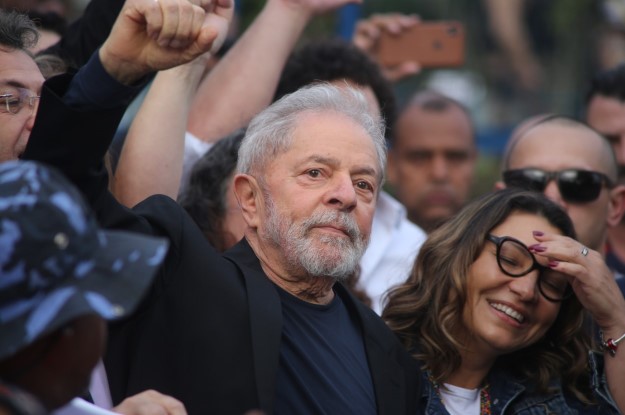

“It’s also in your hands to prevent the return of corruption and robbery to take hold of the country…It’s you who can prevent the release of a prisoner [Lula] convicted of corruption”

—Geraldo Alckmin speaking during his 2018 presidential campaign. Four years on, the former governor of São Paulo is now Lula’s vice-presidential running matein the October 2022 presidential election.

Part 1

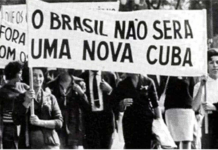

For traditional progressive forces in Brazil, Latin America’s pink tide resumes its stride when Luíz Inácio “Lula” da Silva is re-elected for a third term as president. It’s a sentiment rooted in the size and geopolitical importance of the country. South America’s giant is, by far, the largest land mass, population and economy in the region. It fluctuates somewhere in the top 20 list in each category worldwide.

Similar enthusiasm for Lula’s return to office pervades the region particularly, and the Global South generally. Considering the dearth and tragedy of Brazil’s present political conundrum and that Lula leads all presidential polls against his main rival, incumbent president Jair Bolsonaro, they have good reason.

Lula’s two-term presidency (2003-2011) was no fluke, much less a disappointment. Coming after three failed campaigns (1989, 1994, and 1998) at the Palácio do Planalto, the official workplace for Brazil’s head of state, tens of millions were lifted out of poverty. The UN World Hunger Map axed Brazil from its inglorious list. Bolsa Familia (Family Grant), started just two years into Lula’s first term as president, provided monthly stipends to guarantee basic needs of poor families. Tack on Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff, also a Workers’ Party (PT) member, and Brazil’s government, during a thirteen-and-a-half year period, built 422 technical schools, 18 public universities and 173 new university campuses, surpassing the total number of educational institutions built in the country’s entire history.

Unlike Brazil’s current head of state, an object of envy for the likes of Fox News’ Tucker Carlson with his recent pro-Bolsonaro coverage in Rio de Janeiro and Brasília, Lula’s presidency represented a shining light for large sectors of society, mainly the poor and working class—a glimmer of hope carving out the beaten path of the country’s violent, racist and socially divisive track record. Indeed, Da Sliva left office with a record high 90% approval rate.

However, Brazil’s 2022 presidential election comes not only with a caveat, but baggage. Heavy baggage. Ignored by corporate, alternative and progressive media outlets, it weighs massively on voters ready to cast their ballots for Lula. The elephant in the room has left supporters of the former president, the most popular in Brazil’s history, baffled. A rudimentary, unanswered question prevails among them: What possessed Lula, or his presidential campaign strategists, or his political party, or all of the above, to choose former São Paulo governor Geraldo Alckmin as his vice-presidential running mate?

For seven years I lived in Brazil. The majority of my time was spent in the northeast of the country, Lula’s stronghold of support and the region where he was raised in abject poverty, drought and social deprivation in the interior of the state of Pernambuco. Conditions were so bad that they, like so many other families, migrated south to the state of São Paulo in search of greener pastures.

It was here that Lula, as a young boy, got his start in the informal labor market, shining shoes to help put food on the table. His formal education was as precarious and formative/instructive as his childhood, a far cry from the silver-spoon upbringing most Brazilian politicians are known for. Having completed just the sixth grade, Lula would face the presiding judge in his presidential swearing-in ceremony and say, “If anyone in Brazil doubted that a metal lathe worker would emerge from a factory plant and ascend to the presidency of the Republic, I, in 2002, proved them wrong. And I, who on so many occasions was accused of not having a university degree, earn, as my very first diploma, my country’s presidential republic diploma.”

During Lula’s two-term presidency, some supporters and detractors of the PT would openly discuss and debate the separation of Brazil’s northeastern and northern regions from the rest of the country. Such conversations were taking place while I was in Salvador and Prado. Memories of Quilombo dos Palmares (1597-1695), led by Ganga Zumba and Zumbi, as well as Arraial de Canudos (1893-1897), an independent community led by Antonio Conselheiro, a messianic preacher and forerunner to liberation theology.

Taxes demanded by the newly formed Brazilian republic, he refused to pay. Born from the country’s northeast, all of this mobilization and armed resistance against the southern and central regions of Brazil, and eventually its military and paid mercenaries, added zeal for those arguing in favor of independence.

For three years (2006-2009) I resided in Prado, a small coastal town in southern Bahia. During this period, I became close friends with members of the Rural Landless Workers movement (MST). They lived in Primeiro de Abril (First of April) and Riacho das Ostras (Oyster Creek) encampments, small family farmlands long and hard fought for by the poor and forgotten.

Like most MST camps, First of April and Oyster Creek represents years, even decades, of struggle against latifundios—large private landowners buttressed handsomely on defunct, unproductive yet arable land or monoculture fields. Eventually, after years of grassroots organizing and mobilizing, plots in Prado would be expropriated by the federal government as part of its agrarian reform program.

Still, southern Bahia is known, infamously so, for its hectares upon hectares of eucalyptus trees. Raised on industrial plantations, this monoculture is cultivated to produce paper, pulp and other cellulose-based products. A crop of high-intensity water use, it has dried up local rivers and their tributaries, impoverishing the soil and making it increasingly difficult for MST and other small family farmers to sustain and diversify their agricultural produce.

My First Hearing of Geraldo Alckmin

My stay in Prado came at the tail end of Alckmin’s governorship of São Paulo (2001-2006). People had much to say about his administration being that the capital city, with its 12 million residents, the largest in South America, and bearing the same name as the state, is Brazil’s financial hub.

Naturally, discussions with my MST friends would take a particular direction whenever Alckmin appeared on TV or was the subject of casual conversation. Nevertheless, talks of this nature were echoed by most with whom I spoke. Point blank, the governor represented, first and foremost, the financial interests of Brazil’s elites and the rich, only pandering to the poor to shore up votes when necessary.

His administration was marked by too-many-to-name political corruption scandals. Two of note involved the embezzlement of public funds in the development of public metro works and theft of approximately $1.6 billion reais (approximately $308 million U.S. dollars at current—August 18—exchange rate) of public funds earmarked for school lunches. The latter scheme involved five criminal gangs operating in cahoots with lobbyists submitting public contract bids in 20 statewide municipalities. According to investigators, 85 people were involved, including 13 serving mayors, four former mayors, a city councillor, 27 unelected public officials, and 40 individuals in the private sector. Contrary to Lula’s leadership as president, encouraging investigations of political corruption, including accusations leveled against his own party, Alckmin quashed more than 60 public inquiries into political fraud and corruption during his governorship.

Magnetic North Poles Facing Each Other

Alckmin, a co-founder and former leader of the right-to-center Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB) for 33 years, proved a bitter adversary to Lula and the PT. Profoundly evident was their fiery collision course. Nothing could have remotely hinted at an eventual political alliance between the two more than a decade and a half later.

José Alencar, an entrepreneur and businessman in the textile industry and Minas Gerais state senator, representing the right-of-center Brazilian Republican Party (renamed Republicans), served as Lula’s vice president during his two-term presidency. Their coalition, materializing only after Alencar accepted an invitation by Lula to join the PT, was not between two political figures with a history of relentless public disputes.

A few weeks ago I asked two friends, both MST grassroots loyalists, about the Lula-Alckmin combine. I was curious to hear their opinions about what was going on and what the alliance meant to them. One lady quickly shunned my query, responding that she was “anything but interested to comprehend the reasons” behind Lula’s choice or acceptance of Alckmin as his vice-presidential running mate.

A staunch supporter of Lula and the PT when I was in Prado, campaigning on the streets with family, friends and comrades donned in their red and white banners, hats, and t-shirts, I now detected a sense of disappointment and incredulity, maybe even betrayal in her response. No fan of Bolsonaro and his disastrous administration, there was zero chance she will vote to keep him in office and Lula out. However, she was certainly getting on with her life regardless of the political intrigue and election outcome.

Equally disaffected yet less soft-spoken, the other lady commented that “Lula better be very careful with such an alliance, otherwise, it may spell the end of the PT.” She concluded, emphatically, that Alckmin “does not represent our political struggle.”

Convenient Switch of Sides?

Late last year, Alckmin abruptly and surprisingly renounced membership in the PSDB, the very political party he co-founded in 1988 and joined the left-of-center Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB). His new political membership, sealed in December 2021, occurred just ten days prior to the deadline for presidential hopefuls to be officially registered with a political party. The move opened the door for a possible run as vice president alongside Lula.

Negotiations were held between Alckmin and the former president prior to his departure from the PSDB. At the time, Lula stated that whether or not Alckmin would run as his vice-presidential candidate was “a process under discussion.”

While some sectors of the PT expressed reservations and resistance to Alckmin locking arms with Lula, the party’s president, Gleisi Hoffmann, sounded more upbeat. She described the bond as a “mobilization of forces to bring an end to the current period of suffering, regression and actions that strip hope for the people of Brazil and future of the country. Attending Alckmin’s PSB filiation event, Hoffmann concluded that such a move “has never been so necessary in order to mobilize forces throughout our country.”

Meanwhile, PSB president Carlos Siqueira, emphasized that the 2022 presidential race will not be a competition between the left and the right, rather “between democracy and arbitrariness, between civilization and barbarism.” He went on to stress that “we must acknowledge that this nefarious figure (Bolsonaro) who governs our country is the result of our own political bankruptcy. Although we have produced great social achievements, our system has now reached the point of deterioration where it has allowed such an inexpressive individual to emerge from the National Congress and reach the presidency of the republic. This anomaly must come to an end and it will only come to an end if we exhibit the grandeur and capacity to broaden our horizons.”

Explaining the Inexplicable

Like Hoffmann and Siqueira, other traditional progressive leaders in Brazil have voiced their opinions to justify the Lula-Alckmin merger. The prevailing argument is that the move broadens PT’s support base by redirecting votes to Lula-Alckmin from sectors of the right wing displeased, for whatever reasons, with Bolsonaro’s administration.

The result: Lula wins a resounding first round presidential election victory, consequently, giving his administration a robust mandate to correct the wrongs committed ever since Dilma was impeached—victim of a parliamentary coup—in 2016. Social policies that attend to the needs of Brazil’s poor and working class would resume alongside economic development, trade, and commerce, including the promotion of regional ties and global cooperation, tried and tested formulas that will catapult the country back into the good graces of the international community, moreover, reconstituting a strengthened pink-tide front.

Seen in this context, Lula’s decision to appoint Alckmin has merit. While the political landscape does not signify radical change, people are anxious, desperate to resume a sense of stability, the kind they have grown to appreciate even more when Lula held office. Also, this time around, supporters expect improvements and Lula, despite Alckmin’s recent embrace of left-leaning politics, embodies their hopes.

This position reminds me of a young man I was introduced to while living in the state of Rio Grande do Norte. Having previously worked as a photo journalist for corporate media in the capital city of Natal, he had become thoroughly repulsed by the industry. When passing nearby a Lamborghini, Mercedes, or any other luxury vehicle that could only be the property of pampered, obnoxious moneyed folks, he would often pull from his pocket a jagged-edged coin, slyly brace it against the exterior car doors, and keep strolling, leaving behind a lengthy scratch.

Several years of working in the fifth estate would afford him the opportunity to buy a small lot and build his home, brick by brick, from the ground up, and eventually quit his job. Recently, he told me that Lula’s embrace of Alckmin represented “a shot fired at one’s own foot.” Still, he reiterated his firm support for the former president, “a return to some degree of normalcy experienced during Lula’s government because, at present, Brazil is terrible.”

Lula and Alckmin were officially registered as running mates on August 6 by the Supreme Electoral Court. That said, many, remain skeptical. “This choice should be made by the party,” said former PT president, Rui Falcão. “Lula thinks that he needs to broaden his support base and has looked for alliances which, in the past, have not been alongside us.

The Lula-Alckmin ticket, a political pill few imagined having to swallow, is not the easiest to digest. While the strategy of broadening the base makes sense, it also implies that Bolsonaro’s re-election campaign may not be as downbeat as exit polls suggest and that the incumbent president stands a fighting chance against Lula. Taking Alckmin on board before a hotly contested vote, which the Brazilian presidential election will be, preemptively avoids having to form a coalition government with elements of Bolsonaro’s camp.

However, Alckmin’s abrupt conversion from one side of the political spectrum to the other, followed by Lula’s welcoming of his long-time political rival, may indicate something more machiavellian at play.

Stay tuned to CovertAction Magazine for the forthcoming Part II of “Is Lula Under Threat?”

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com

What it seems invisible for most analysts is the fact that Lula was not a “Revolutionary” as many would like him to be. Yes, he did improve the general living conditions of the poor. At the same time, he also approved giant mergers of financial institutions. At the beginning of Lula’s first term, the country had 36 banks. At the end only 5. Credit card rates in Brazil are in the house on hundreds percent/year, something unheard of before his baking system reforms. He introduced the poor to the credit system and stimulated shopping at a rate that never happened in Brazil. Under the guise of extending Education for all, American social ideologies made deep inroads in Brazilian intellectual, which also counts for the extent of social hostilities in the country now. Jair Bolsonaro came and fanned the flames for his own gain. Lula loves power. He always did. he played the Social Hero card to perfection but back in the days as worker’s hero, many already knew he would do anything to grab power and never let it go. The MST activists ( the ones not sold out) will frankly say the truth which is that during Lula’s tenure they gained next to nothing. The land reforms heralded prior to his first election never materialized. Dilma Rousseff his successor and puppet ( he talked to her over the phone every single day to discuss government matters) followed the same path, paying and feeding in the emotions of the needed. As for the allegiance with Alckmin, it’s all about power for both. Alckmin left the São Paulo state government in disgrace, due to a scandal concern misappropriation of children’s public school lunch. He went out to resume his studies and let time go by to make a come back. H hopes to do it with Lula. An interesting fact is that Leonardo Boff, Lula’s oldest friend and advisor has recently stated that the Amazon Forest should be Internationalized. That’s the kind of “social justice warrior” we find in Lula’s company.

[…] Is Lula Under Threat? Political Intrigue Grows As Right Suddenly Merges With Left In Brazil’s Upco… […]

[…] Por Julián Cola, publicado en Cover Action Magazine […]

hy

As a Brazilian, I can confirm that the general sense, besides disappointment with bringing in Alckmin, is that Lula is at a big risk.

We haven’t forgotten the 2016 coup. The party responsible for it, PMDB, was allied with PT since the 2002 elections, and voted mostly for deposing her. The article also doesn’t state how irresponsible Alckmin was during the Cantareira water crisis in 2014, an election year, where he repeatedly said during interviews that “there’s no water crisis” while running for governor of Sao Paulo.

There’s a very real chance that Lula might die before the end of his term, if he wins this year’s elections, either by natural causes or, as is commonly said around here, by “being suicided” (this a reference to how the 1964-84 dictatorship would murder people and claim they committed suicide). Even if Lula’s health gets him to 2030 and beyond, unless the majority of Congress deputies are also from PT, another coup will be easy. The prospect of having someone as corrupt and conivent as Alckmin would make over half of the current deputies salivate with possibilities. Not only that, the super rich know Alckmin would be a lot more likely to approve laws that favor them. The brazilian economic elite is extremely hateful against the poor and even more so against Lula, especially the big media (Globo, Folha de Sao Paulo, Estadao).

I hope Lula gets elected and manages to get to the end of this term safe and sound, but I’m not holding my breath. As an old poet once said, regarding how surreal the country is, “Brazil is not for amateurs”.