Florida’s State Attorney said it was too much of a coincidence that the riot broke out at the same time that “Tricky Dick” was making his nomination speech stressing a law and order theme

[In recent years, U.S. government leaders and their media echo chambers have repeatedly accused Russia of interfering in U.S. elections. Historically, however, it is the U.S. which has a long record of subverting democracy in foreign nations, including Russia itself where the Clinton administration intervened to support the re-election of Boris Yeltsin in 1996.

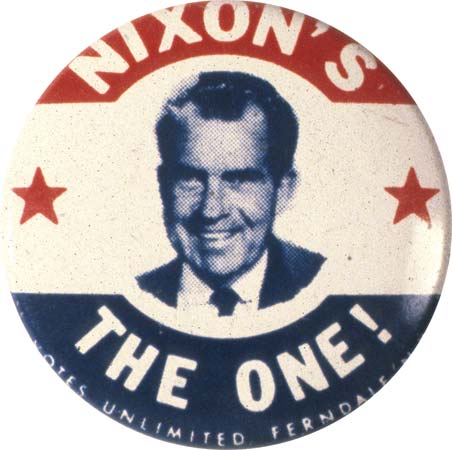

Robert Aldridge’s article below presents evidence that the U.S. government and CIA may have schemed to manipulate the outcome of U.S. presidential elections along with foreign ones. Aldridge focuses on the 1968 elections in which the CIA may have aided the Republican candidate, Richard Nixon, by helping to foment a race riot near the Miami Beach Convention Center where he secured the presidential nomination. The purpose of the riot was to sway voters to select Nixon as the “law and order” candidate over his more liberal rival, Nelson Rockefeller. The CIA wanted Nixon because he was a war hawk who, despite his claim to want to seek “peace with honor,” went on to expand the Vietnam War. The two men tasked with writing the official report about the riot, Louis J. Hector and Paul Helliwell, had backgrounds in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and CIA and whitewashed what actually happened—in a way reminiscent of the Warren Commission and other government cover-ups.—Editors]

1. The major issue in the 1968 U.S. presidential election was the Vietnam War.

The Vietnam War had became Americanized with the passage of the Gulf of Tonkin resolution in 1964, but by 1967-68 the war had become unpopular with much of the American public, and was the major issue in the 1968 presidential election. In March 1968 President Johnson announced that he would not run for re-election. Early on, liberal Democratic Senators Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy ran for the Democratic nomination promising a quick withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam. Republican candidates were divided on the issue: Liberal Republicans like Nelson Rockefeller and George Romney promised a quick withdrawal, while conservative Republicans like Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon (who had been a staunch anti-Communist when he was vice president under Eisenhower) were committed to continuing the war.

2. CIA involvement in the 1968 presidential election.

The CIA was fully committed to stopping the spread of Communism across the world and, therefore, conducted secret political operations inside the U.S. to derail Democratic and liberal Republican presidential candidates in the 1968 presidential election. (The CIA’s secret intervention in the 1968 election is detailed in “Did the CIA Subvert the 1968 U.S. Presidential Election?” in the June 2, 2022, posting of CovertAction Magazine.) The present article seeks to show that the CIA created the 1968 Liberty City riot (in Miami) to ensure Nixon’s victory at the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach in August 1968.

3. Urban riots between 1964 and 1969.

In the “long, hot summers” between 1964 and 1969 there were more than a hundred Black urban riots (Los Angeles, Detroit, Harlem, Cleveland, Newark, etc.) caused by the gap between the legal success of the Civil Rights Movement (the Civil Rights legislation of 1964-65) and the continued existence of white racism and the low level of implementation of equality for Blacks in all areas of American society (such as education, employment and housing).

The riots were a polarizing force in American society. For some, they were striking evidence of the need for further action to implement civil rights for those who had been denied them for so long. For others, they sharply demonstrated a need for stronger law enforcement to protect lives and property. Black civil rights and social equality was an important issue in the 1968 election, which was supported by most liberals and rejected by those who supported white supremacy and opposed integration.

4. The 1968 Republican National Convention in Miami Beach.

The 1968 Republican National Convention was held in Miami Beach, Florida, August 5-8, at the Miami Beach Convention Center. Most of the 30,000 attendees (1,333 were delegates) arrived before August 5 and filled Miami Beach hotels. Both Nixon and Rockefeller brought staffs of about 200.

One of the Republican delegates was basketball star Wilt “the Stilt” Chamberlain, who had become a Republican and accompanied Nixon to Martin Luther King’s funeral in April 1968. Rev. Ralph Abernathy, who had succeeded Martin Luther King as leader of the Poor People’s Campaign, led a protest delegation to the Republican Convention. After initially being barred from the Convention Center, an agreement was reached allowing Rev. Abernathy and a small number of supporters to sit quietly in the Convention Center lobby.

5. The Nixon-Rockefeller contest at the Convention.

The Convention opened at 10 a.m. on Monday morning, August 5. There were four major Republican candidates: former Vice President Richard Nixon (California), Governor Nelson Rockefeller (New York), Governor Ronald Reagan (California) and Governor George Romney (Michigan), as well as a number of “native son” candidates. But Romney and Reagan had little support and the real contest was between Rockefeller and front-runner Nixon. Nixon arrived at the Convention with many more delegates than Rockefeller, but not enough to win the nomination on the first ballot. Nevertheless, Rockefeller’s chances of beating Nixon on the second ballot were good. Political historian Theodore White later wrote:

All through the year, from January on, Nelson Rockefeller had outpolled all other Republicans—Romney, Reagan, Nixon himself. Rockefeller’s strength lay outside the convention, outside the Party, in that broad and shifting mass of independents and shallow-anchored Democrats he had so consistently drawn to his support in his home state. If the party did want a winner, then Nelson Rockefeller was its surest winner—his job was to persuade the delegates that the mirage was real, that the surest guarantee of victory in November was the Rockefeller magic.[1]

But in the opening days of the Convention front-runner Nixon was losing Southern delegates to newcomer Reagan, because many Southern conservatives saw Reagan as a right-winger opposed to eastern liberals. This was reducing Nixon’s lead over Rockefeller. On Monday a number of Southern delegates said they would vote for Reagan if Nixon did not win on the first ballot. British journalist David English wrote:

If the southern vote went to Reagan and Nixon failed to win the nomination on the first or second ballot, it was possible, even probable, that his support would fall away and that the battle would resolve itself between Reagan and Rockefeller; in that case Rockefeller would almost certainly win.”[2]

On Wednesday morning Nixon’s strength eroded further as 14 more delegates declared for Reagan.

6. Candidates’ positions on Black urban riots.

Both Rockefeller and Romney not only supported a quick pull-out from Vietnam, but were also liberal on social issues. Rockefeller believed the correct response to Black urban riots was to create or expand federal programs that would re-develop inner-city areas and alleviate Black poverty. Nixon ran on a campaign that promised to restore “law and order” to America’s cities, which were torn by riots and crime, and to its colleges and universities, which were besieged by anti-war demonstrations. Nixon also opposed busing (transporting Black students from inferior Black schools to more affluent white schools).

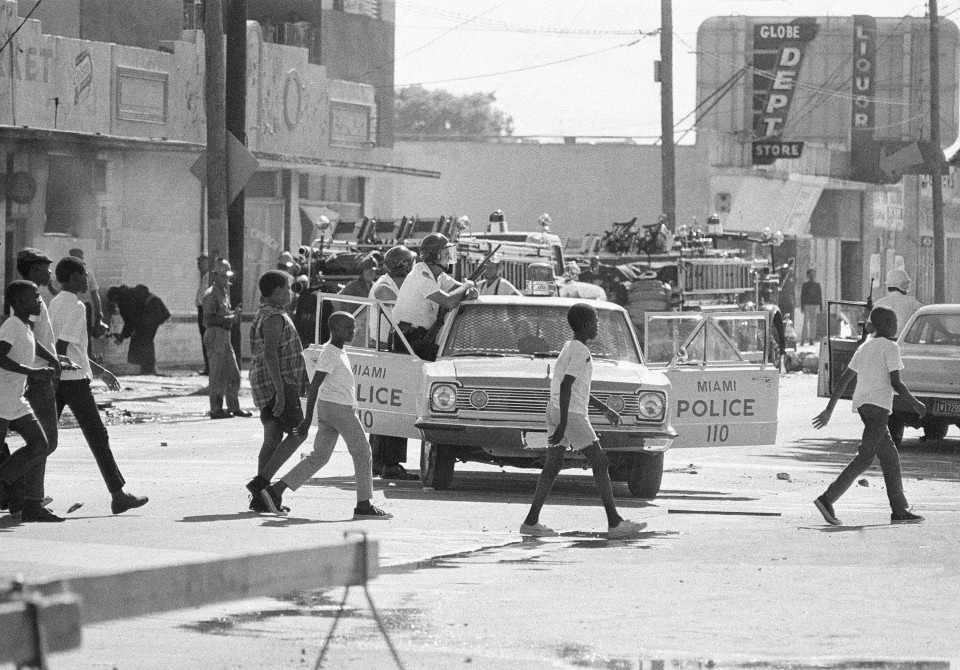

7. On August 7 the Liberty City riot began and the Convention voted.

Wednesday, August 7, was the day that the Republican National Convention voted to select their presidential candidate. It was also the day of the first Black riot in Miami history. Two events on Wednesday were connected with the riot’s beginning: the “Vote Power” rally held about 1 p.m. in Liberty City (one of the three historically Black neighborhoods in Miami) on the western end of NW 62nd St.,[3] and an incident involving a car with a George Wallace[4] sticker on the central portion of NW 62nd St. at perhaps 1:30 p.m.

On Friday, August 16, the Miami Times, a Black weekly newspaper in Liberty City, printed this account of events preceding the riot and of the riot’s start:

The first night of the Republican convention was a failure to Miami’s blacks who had planned a massive rally to protest the alleged racial policies of the Republican Party.

The next night, a group of blacks attempted to demonstrate in front of the Convention Hall where the convention was being held, but this effort also proved a failure.

So the group planned a third show of strength. They invited Rev. Ralph Abernathy, president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and Wilt Chamberlain, a professional basketball player among the list of impressive speakers to address the massive rally outside a storefront at NW 62nd St. and 17th Avenue…

The crowd that gathered at NW 62nd Street and 17th Avenue was young and angry. And it exploded…

The widely circulated flyer advertising the meeting said the speakers would include representatives from the United Black Students, the Black Panthers, the Congress of Racial Equality, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and a black power group known as B.A.T.E.

Hosea Williams, demonstrations director of the SCLC confirmed that Dr. Abernathy was scheduled to attend the mass rally.

“He was supposed to close it out,” said Williams. “We were not knowledgeable of the activity that was supposed to take place from 1 to 7.”

The mass rally was scheduled to last for 12 hours, from 1 p.m. Wednesday to 1 a.m. Thursday.

Rev. Abernathy and Chamberlain were the most impressive of the list of speakers scheduled to attend the rally, and when they didn’t show up the crowd began to heat up.

Chamberlain…confirmed he was scheduled to appear, but said his appearance was to be late in the night.

The action appeared to have been triggered further with the attempt by a white Miami Herald reporter, who attempted to attend the mass rally. Officials of the rally had earlier indicated to the news media that a “black only” policy would be observed.

The Herald reporter was bodily carried out by three blacks when he refused to leave the meeting.[5]

About this time, because of rocks being thrown at passing cars, locals began calling the police requesting 62nd Street be barricaded from all traffic. Some also requested that only Black police officers be sent in to handle the situation, a tactic Mayor Carl Stokes had used in the Cleveland riot two weeks earlier. The police refused, however, and later defended their refusal saying that barricades “weren’t necessary at all. They would have only incited, rather than calmed, the situation.” The Miami Times report continued:

[After this] a yellow Mercury bearing “Wallace for President” stickers on its bumpers drove through the disturbance area.

When the driver reached 15th Avenue, the car stalled. Rocks pelted the car, and the driver, his face bloodied, was helped out of the car through the back door of a bar and then to a hospital.

The car was overturned and a cheer went up. Then a match was dropped into the gas tank and the car exploded into flames and heavy smoke.

Miami’s first racial violence had begun.

The Miami Times is a weekly newspaper (every Friday) whose article on the riot appeared more than a week after it happened and its account was not used by any national newspaper.

On Thursday, August 8, the Miami News, a daily newspaper,[6] reported that a participant said “we saw this 1968 Mercury driven by some honky (white man) and hell man, it had a George Wallace for President bumper sticker on it.”[7] The Miami News reported that the witness went on to say:

“The man, after being barraged by the brothers with rocks and bottles, rammed into a delivery truck headed west on 62nd Street. The truck made a U-turn in the street and started back the other way,” he said.

The other driver stalled in the intersection. He attempted to get out of the car at least 12 times, but a group of Negro youths shoved him back inside each time.

The youths beat and stoned the man before he was able to stagger into the Liberty Bar, covered with blood. The crowd cheered as the man was beaten.

The youths were then joined by others who turned over the car and dropped a match into the gasoline tank. Cheering and laughter rang out as the car burned.

On Thursday, August 8, the day after the riot began, the Miami Herald printed this account of how the riot began:

Shortly after the “Vote Power” meeting was scheduled to begin at 1 p.m., Miami Herald reporter Mike Toner was asked to leave the room. After he refused twice, three men picked him up and carried him from the hall. Toner was not injured, but two other newsmen were ejected and roughed up at the same meeting about an hour later.[8]

The Herald seems to have printed this story, involving one of their own reporters, because due to the violence other reporters had not been able to speak with people at the scene of the riot. This initial account was picked up by newspapers across the country. On Friday, August 9, the Miami Herald revised its account of how the riot began, noting that there was no police response for the first two (or more) hours, allowing the riot to expand greatly and get out of control:

The first outbreak occurred on Wednesday when a car with a George Wallace bumper sticker ran into another car near a surging angry crowd. The crowd turned over the car and set it afire. The driver escaped with serious injury.[9]

Only a few hours before, white newsmen had been ejected forcibly from a black “Vote Power” rally.[10]

Metro Mayor Chuck Hall was known to have blamed some of the daylight trouble on City Manager Melvin Reese – for delay.

Miami Mayor Steve Clark made repeated calls to Reese for about two hours from a Manor Park Community Center command post.[11]

About 3:30 p.m. Reese agreed to declare an emergency, one source said.

The Rev. Theodore Gibson, a prominent Negro churchman, said bitterly, “They were too late, just too late.”[12]

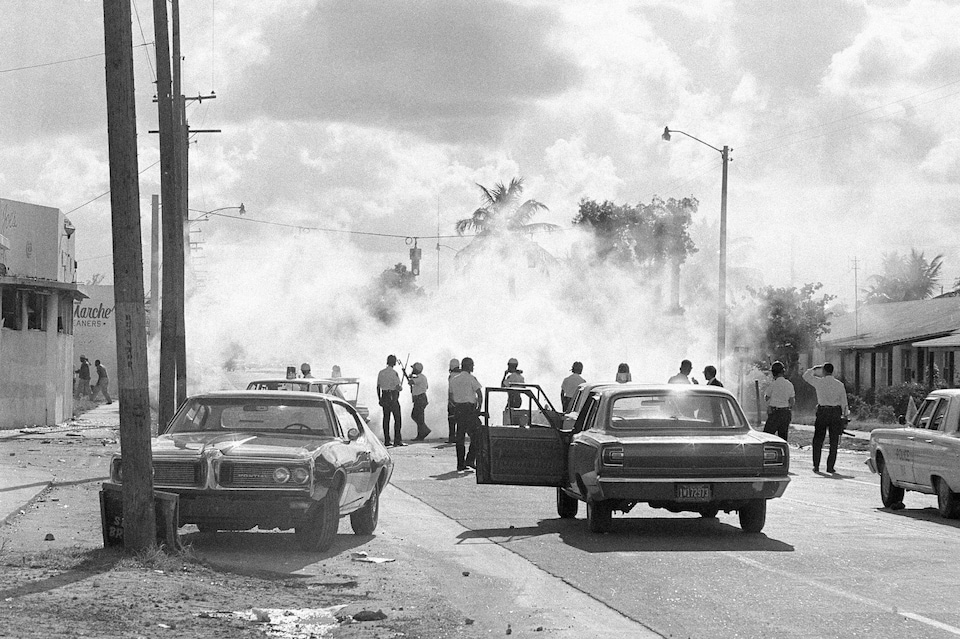

8. The riot escalated in mid-afternoon.

According to the Miami Herald account, from about 1:30 to 3:30 p.m., the mayor made repeated calls to the city manager to declare an emergency (i.e., call in the police, fire department, ambulance crews, and the National Guard).[13] The incidents at the rally escalated to a civil disturbance in the central portion of NW 62nd St. (around the 1400 block), and from there it expanded to a large riot in the next few hours. According to the Miami News, “most of the trouble took place in a 10-block area along NW 62nd Street from NW 7th to 17th Avenues.”[14]

At this same time (1:30 to 3:30 p.m.) there must have been hundreds of phone calls from businesses and residents in the affected areas of Liberty City reporting the rioting and looting. And, in addition, according to the later official investigation, the rally was under police surveillance (both open and undercover) the entire time.[15]

But there was no police response until some time after 3:30 p.m.—two hours later. The police command center chose not to respond to the escalating riot—even though their own undercover units at the scene were reporting the deteriorating situation.

When the police finally responded in mid-afternoon, a full riot was in progress. The Miami Herald told how one business was looted several times:

At one point in mid-afternoon, five city policemen discovered themselves trapped inside the twice-burned thrice-looted M and M Liquor store. Shouting black men had their squad cars hemmed in.

A brick struck Officer Joseph Mullen in the back of the head. Major Adam Klinkowski grasped the injured officer and pushed him toward another squad car – already occupied by two Negro prisoners.

The crowd angrily began to rock the squad car back and forth. Police released the two men.

“When we got out of the store,” said Officer James J. Welch, “they were screaming for us to leave.

“But they cleaned out the place right there in front of us. It was unreal. I figured we were finished.

“You know you don’t want to shoot anybody – as long as they’re throwing things you can try to dodge.”

Another officer came up with a quick solution to the brick throwing.

“We handcuffed a prisoner and put him on top of the car. You better believe that stopped the brick throwing.”[16]

9. Questions about what triggered the riot.

The disturbance had deteriorated into a full-blown riot before the police responded effectively. Why? Florida’s State Attorney later said, “It’s just too much of a coincidence that we’re having this riot at the same time as we’re having the Republican Convention and Richard Nixon’s making his nomination speech.”[17]

The “Final Report of the Grand Jury” (cited above) stated that, in light of the low level of racial tension in Miami, “it seems more than mere coincidence that these acts of lawlessness took place at a time when they could be publicized most widely by the national news media that was covering the Republican Convention only a few miles away in Miami Beach” (p. 6).

On Thursday, August 8, the Miami News reported that “Mayor Clark told newsmen at the park command post that negro residents of the area felt the violence was the work of outside agitators. Mayor Clark said residents told him the troublemakers were egged on by persons new to the community.”[18] On Friday, August 9, the Miami News article “Negro Leaders Blame Outsiders” repeated further claims that the riot was not started by Liberty City residents.[19]

10. The riot escalated further on Wednesday evening.

The Miami Herald reported on Thursday morning (August 8) that by Wednesday evening “more than 200 uniformed city police were ordered to the scene of the original disturbance and they were backed up later by 300 sheriff’s men.” The Herald continued, saying that after intermittent trouble on Wednesday afternoon, the strife “culminated in the tear gas barrage and police flying wedge several hours later. The worst of the tense situation came between 8:30 and 9 p.m.”[20] The same Herald report also said that, on Wednesday night and early Thursday, “at least 14 persons were injured and 85 arrested…In addition, police said at least 35 stores of various types had been broken into and many looted. At least two were severely damaged by fire.”[21]

11. Media reporting on the riot Wednesday afternoon and evening.

According to the Miami Report (the official report on the riot which will be considered below), when the “Vote Power” mass rally began at 1 p.m. on Wednesday, “several local news reporters, at least two television network reporters, and one TV cameraman were on the scene.”[22] The Miami Report also stated that “local radio reports seem to have attracted additional people to the riot area.”[23] The media reported on the riot during the convention. On August 8, 1968, the Miami News reported:

Much of the listening national TV audience heard Rev. Abernathy make an anxious appeal over the NBC network from the convention floor asking “my brothers and sisters here in Miami” to halt the violence.

Rev. Abernathy, head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, urged the demonstrators to “go home and let us abide by the law”…

At least 10 persons were injured and treated at hospitals. Among them were four newsmen including a CBS camera crew.[24]

12. Voting Wednesday evening at the Convention.

The Republican Convention at the Miami Beach Convention Center began placing names in nomination at 5 p.m. on Wednesday evening. About this same time Miami TV reported that “seventeen policemen armed with shotguns were moving into the combat area” (i.e., central Liberty City). Before the first ballot, Nixon had 613 votes committed to him (54 short of the number needed to win), 272 were committed to Rockefeller, who hoped to do some serious deal-making after the first ballot, and 448 were uncommitted or committed to other candidates.[25]

Two of the main things in the Miami news that evening were the Republican Convention and the rioting in Liberty City—seven miles northwest of the Convention Center, on the other side of Biscayne Bay. Many delegates would have been aware of the riot from their transistor radios and the TV in the Convention Center’s lobby.

By evening there were police barricades at the western end of the Julia Tuttle Causeway—the middle one of the three causeways connecting Miami to Miami Beach—to prevent rioters from reaching Miami Beach and the Republican Convention. (The next day rioters breached the causeway barricade and came within one mile of the Convention Center.)

Nixon’s “law and order” platform and the nearness of the riot seem to have swayed many delegates to Nixon. Voting began at 7 p.m. and finished at 1:30 a.m. Nixon won on the first ballot with 692 votes (79 more than had been committed to him), to 277 votes for Rockefeller (5 more than had been committed to him), and 364 votes for Reagan and eight other candidates.

Almost 80 delegates had switched from other candidates (and uncommitted) to Nixon, likely due to the riot on the other side of Biscayne Bay. The riot in Liberty City robbed Rockefeller of the opportunity for second-ballot deal-making, and clinched the Republican nomination for Nixon. In his acceptance speech that evening (in the early hours of August 8), Nixon said that “the nation with the greatest tradition of law is plagued by racial violence.”

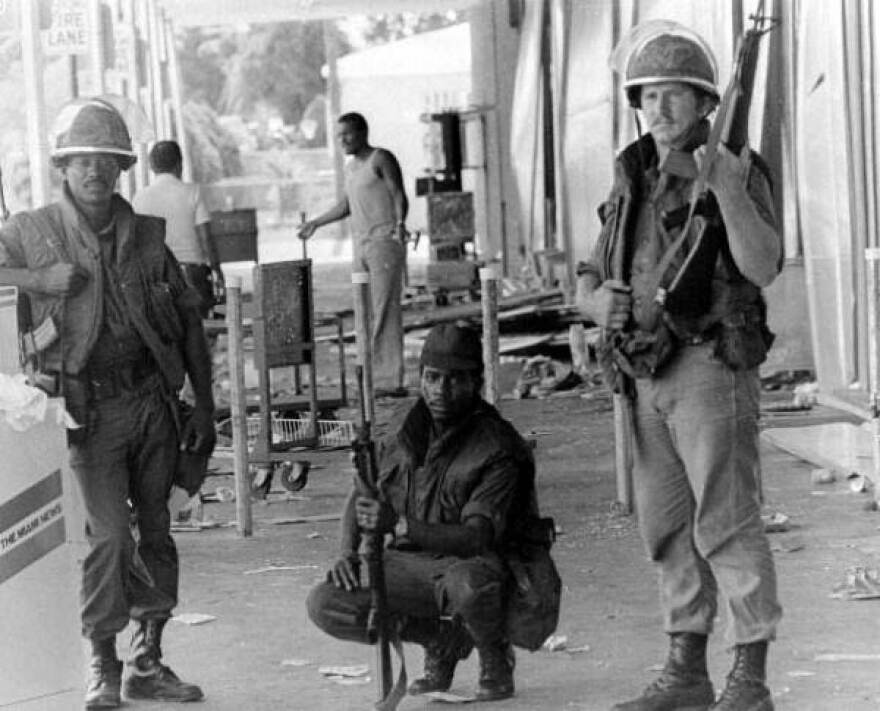

13. The riot continued on Thursday and Friday.

Shooting, looting and killing continued on Thursday. On Friday, August 9, the Miami Herald reported:

Six hundred Florida National Guard troops moved into Miami’s violence-torn Liberty City Negro district Thursday evening as gunfire killed three men during a day and night of looting, firebombing and racial disorders.

Sheriff Wilson Purdy, appointed commander of all forces by Gov. Claude Kirk, ordered a curfew of a 555-block section of the city. Two forces of troops, carrying everything from flame-throwers to sawed-off shotguns, swept in force into the heart of Miami’s black ghetto, effectively cutting Liberty City in half…

The Guard alone wasn’t enough. Another 400 men, Miami police, sheriff deputies and state troopers, attempted to control spasmodic outbreaks throughout much of the night.[26]

By Thursday evening 186 persons had been arrested. On Friday there was much less violence and by Friday evening the riot was effectively over, although the curfew remained in effect until Sunday night, along with a reduced National Guard presence.

During the riot property damage ran into the millions (buildings burned down, businesses looted, cars destroyed, etc.), the livelihoods of many business owners were destroyed, three people were killed,[27] 43 people were injured (many seriously),[28] hundreds were arrested, and the city, county, and state spent millions responding to the situation (not only with the police, National Guard, fire department, and ambulance crews, but also in jail and public hospital costs). Enormous damage had been done.

14. The riot and the Convention.

It is clear from the preceding information (based on on-the-scene reporting by the Miami Herald, the Miami News, the Miami Times, several major political writers, the grand jury’s Final Report, and other sources) that the Liberty City riot was closely connected with the 1968 Republican National Convention. The larger context of the riot and the RNC was the CIA’s commitment to ensure that a pro-Vietnam war candidate won the 1968 presidential election.

The salient facts include: 1) The Liberty City riot was the first race riot in Miami’s history. 2) The 1968 RNC was primarily a contest between anti-war candidate Nelson Rockefeller and pro-war candidate Richard Nixon. Neither candidate had enough delegates to win on the first ballot.

Although Nixon had a good delegate lead over Rockefeller, Rockefeller was an excellent political “horse-trader” and was expected to win on the second ballot. Rockefeller was also pro-civil rights, while Nixon was pro-“law and order” regarding Black urban riots. 3) The riot started at the exact time and place to influence the Convention’s outcome: several hours before the start of the Convention’s voting, a relatively short distance from the Convention.

4) Liberty City community leaders stated that the riot was created by “outsiders” who egged on the young people (who were there for the rally) to commit further disturbances. 5) For unexplained reasons, after the disturbances began, Miami police held off from intervening in it for several hours, allowing the initial disturbance to snowball into a major riot within an hour or two. 6) The Miami media gave considerable coverage to the riot, which was known to Convention delegates because Reverend Abernathy appealed from the Convention floor (through the NBC network) asking the rioters to halt the violence. 7) 79 delegates were influenced to switch their votes to Richard Nixon, giving him victory on the first ballot.

16. The Miami Report’s conclusions on what caused the riot.

A report on the riot known as the Miami Report stated in its preface:

We are surprised at the extent of the discrepancies between various accounts of the disturbances, even on such simple factual matters as the time and location of single incidents reported by numerous observers. Except in the report on the Central Negro District [pp. 19-20, which covers events on Thursday night, August 8], we have not undertaken to set forth varying accounts of the same episode. We have resolved them as best we could in discussion with our staff, and presented only our conclusions.[29]

In other words, they disregarded almost all of the eyewitness testimony and created their own account of what happened! The incident leading to the riot and the greatly delayed police response in its early stages are among the events that were re-written (or omitted) by the Miami Study Team.

The Miami Report’s summary states: “The disturbances originated spontaneously and almost entirely out of the accumulated deprivations, discriminations, and frustrations of the Black community in Liberty City…”[30] and that no outside persons or groups were involved.[31]

Elsewhere the Miami Report says that “there was no significant direct connection between the Republican Convention… and the Liberty City disturbance.”[32] Instead, the Miami Report placed major blame on the poor economic conditions in Liberty City[33] and the racist policies of Miami Police Chief Walter Headley.[34]

The latter is the major focus and largest part of the Miami Report. One-third of the Miami Report (pp. 33-49, unnumbered) consists solely of Miami newspaper articles on Chief Headley’s “get tough” policy. While these were surely important factors in the anger and frustration of Liberty City’s residents, they do not make clear the actual incidents that provoked the riot.

17. The Miami Report’s account of how the riot began.

The Miami Report narrates the events at the mass rally at NW 62nd and 17th from 1 p.m. on, but reports no violence in the several hours following the start of the mass rally except for some teenagers “throwing small stones at motorists” about 2:30 to 3 p.m. The Report states that:

Until around 3:30 or 4 P.M. the mood of the crowd seemed jovial and the atmosphere somewhat carnival-like. From then on, the crowd grew larger, louder and more restless and unruly. Teenagers, who had previously been throwing pebbles, began throwing larger rocks, bottles and other objects, and they began to single out vehicles driven by white persons as their targets. This conduct continued unhampered by the approximately twenty-five uniformed City Policemen until around 5:00 P.M., and during this time traffic was allowed to flow freely through the area. Several automobile windshields were broken, but no serious injuries to individuals occurred.[35]

The Report next states that police established roadblocks on NW 62nd Street about 6:00 p.m., but that these were lifted by 7:00 p.m. The Miami Report says that it was at this point that the “Wallace sticker” car incident occurred that the Report declares was the start of the riot:

Around 7 P.M. Wednesday, a white was driving east on 62nd Street in an automobile bearing a “Wallace for President” sticker. As he approached 15th Avenue, his car was peppered with rocks…The driver…abandoned the car…

The car was overturned and set afire by a group of black youths. The riot had started.

The automobile burning took place a little after 7 P.M. at N.W. 62nd Street at 15th Avenue, two blocks east of the meeting hall. Immediately afterward groups of black youth commenced looting and vandalizing in the immediate area of the automobile fire and then moved quickly eastward toward the rows of small stores on 62nd Street…Continuing east, the crowds attempted to be selective in their looting by determining whether a shop was black-owned.

As the riot grew in size and intensity, it moved further east along 62nd Street…

Some 300 people appear to have been directly involved in the disturbances which followed the automobile burning…[36]

18. Problems with the Miami Report’s account of how the riot began.

Thus, the Miami Report says that the disturbances on NW 62nd Street on Wednesday afternoon were limited to “rock-throwing” by teenagers. Absent from the Report is the serious rioting started by the “Wallace sticker” car incident about 1:30 p.m. (reported in the Miami Herald, Miami News, Miami Times, and the grand jury’s Final Report), that led Miami Mayor Steve Clark to make repeated calls to City Manager Melvin Reese for about two hours (until about 3:30 p.m.) to declare an emergency so that the National Guard could be called in. Instead, the Miami Report states that the riot began with the “Wallace sticker” car incident, but places that incident at “a little after 7 P.M.”—about six hours after the actual event.[37]

Since the Convention’s roll call was held at 7 p.m. and the balloting began about 7:30 p.m., this would eliminate the possibility that the riot had any impact on the Convention’s outcome (Nixon’s nomination). The timeline of the riot’s start that the Miami Report sets out differs greatly from that given by the Miami Herald and other Miami newspapers and supports its statement that “there was no significant direct connection between the Republican Convention… and the Liberty City disturbance.”

And because the Miami Report places the riot’s start at “a little after 7 P.M.,” it also omits the several-hour delay in police response to the early phases of the riot (reported by the Miami Herald). The Miami Report’s timeline also conflicts greatly with the agreement between the Miami Herald and the grand jury’s Final Report that “the most violent part of the disturbance” occurred during the period between 1:30 and 3:30 p.m. on Wednesday.

The Miami Report’s complete omission of the lack of any police response during the early stages of the disturbances brings to mind the admission of the Report’s creators that they disregarded much of the eyewitness testimony and created their own account of what happened.

The lack of any police response during the early stages of the disturbances allowed those events to snowball into much larger rioting—and may connect with statements by Liberty City community leaders that the riot was created by “outsiders.”

The latter runs contrary to the statement in the Miami Report’s Summary that “few blacks from outside of the Liberty City area appear to have been present during the meetings which preceded the disturbances and they did not play a significant part in the origin or continuance of the disturbances.”[38]

19. Who wrote the Miami Report?

One would think that the official body organized to investigate the causes of such a large riot would consist of an appropriate mix of community leaders, race relations experts, religious leaders, and sociologists. The Miami Study Team, charged with investigating the Liberty City riot and writing the report, was directed by two men, Louis J. Hector and Paul L. E. Helliwell, assisted by two associate directors, five investigators, two editors, and an executive secretary.[39]

In actuality, the Miami Report was created by its directors, Louis Hector and Paul Helliwell, who determined the course of the investigation and had final word on its contents.

20. Who were Louis Hector and Paul Helliwell?

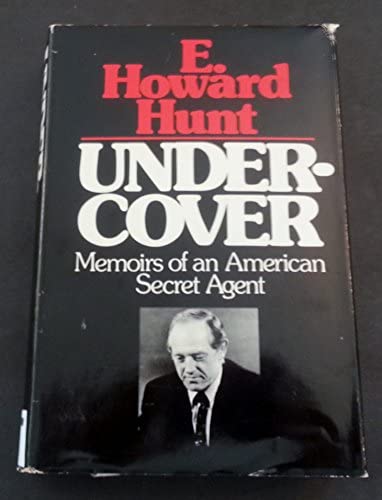

Louis Hector (1915-2005) and Paul Helliwell (1915-1976) were both Florida natives who became Florida lawyers in their twenties, before World War II. During World War II both served in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS—the predecessor of the CIA), both in the 202nd Detachment in Kunming, China.

E. Howard Hunt, a CIA operative who served with Helliwell and Hector in the 202nd Detachment (and later engaged in illegal intelligence operations inside the U.S.), links Hector and Helliwell in his 1974 memoir, Undercover: “Other Detachment 202 figures, who were later to become prominent both in their home state of Florida and nationally, were Col. Paul Helliwell and Rhodes scholar Louis Hector.”[40] Hector and Helliwell were lifelong associates, and both lived much of their lives in the Miami area.

Louis J. Hector received his law degree from Yale, then attended Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. In the early part of World War II he served in OSS, in China. Later in the war he was an assistant to State Deptartment Under-Secretary Edward Stettinius, in the China section of the Lend-Lease Administration.

After the war he distinguished himself as an attorney in private practice and with the Federal government, serving almost 20 years in legal and administrative positions with the Federal Aviation Administration, the Civil Aeronautics Board, etc. He served on the board of directors of Southeast Banking Corp. and National Airlines, and as the director of First National Bank of Miami and Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. He also served at the Brookings Institution, a public policy think tank, and in 1966 became a partner in the Miami law firm of Steel, Hector & Davis (heir to the J.P. Stokes law firm that was instrumental in creating the Florida East Coast Railroad of Henry Flagler, which enabled Miami to be founded and built). His second wife, Nancy, was a friend of the Kennedys and a member of Washington’s inner circle.[41] He died in 2005. His name lent prestige to the Miami Study Group and credence to the Miami Report’s findings.

Helliwell’s life-story was very different.[42] At the beginning of World War II he was with the U.S. Army’s G-2 military intelligence group in the Middle East. Transferring to OSS, he served as chief of the OSS Secret Intelligence Branch in Kunming until 1943, commanding 350 OSS personnel and several thousand Asian operatives and informants. He then became head of the OSS Secret Intelligence Branch in Europe, until he was replaced by William Casey in 1945.

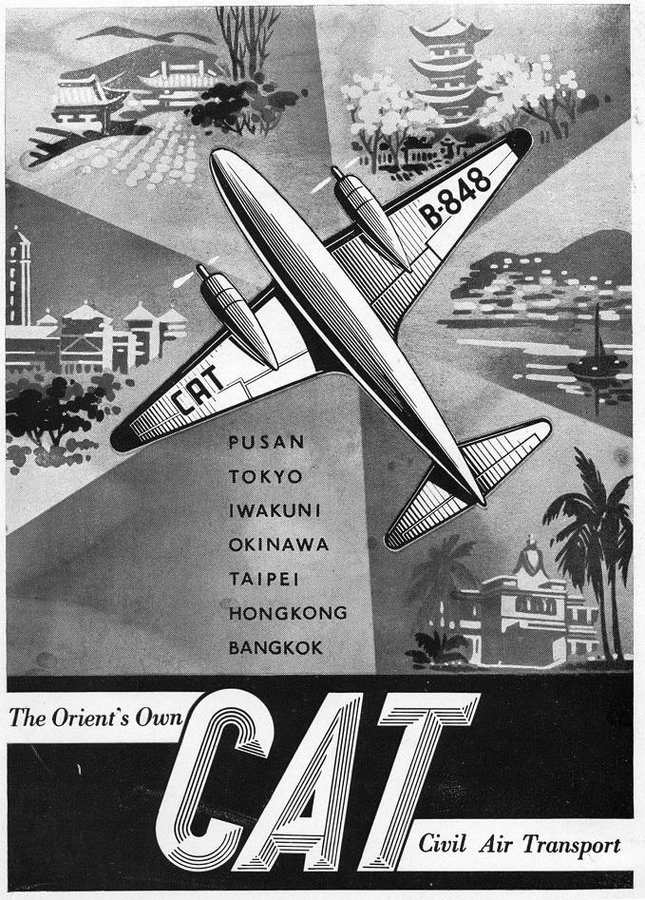

After World War II ended in 1945, the OSS was dismantled and divided between the Army and the State Department. The Army’s outfit, called the Strategic Services Unit, conducted covert operations. Helliwell became chief of SSU’s Far East Division, whose main task was to support the Chinese Nationalists (the KMT) in their civil war against the Chinese Communists. As they were losing the civil war in 1949, the Nationalists fled to Taiwan. One KMT military unit, the Eighth Army, retreated to Burma.

An expert in secret operations, secret weapons shipments, and secret financial transactions, Helliwell created dummy businesses, such as SEA Supply Corp. and Western Enterprises, to import arms to Thailand’s military strongman, General Phao Sinyanon, and to ship weapons to the KMT Eighth Army in Burma (which was supporting itself by growing opium).[43] With Gen. Claire Chennault, he helped found Civil Air Transport and organized the export of opium and heroin from the Golden Triangle (Burma, Laos, Thailand) to Taiwan via C.A.T.

From Taiwan the heroin was smuggled into the U.S. (in diplomatic pouches to the Taiwanese consulate in San Francisco) for distribution in American cities. In 1950 he introduced Gen. Chennault to OPC chief Frank Wisner, who directed CIA covert military operations, which led to the CIA heavily subsidizing (and later partially buying) Chennault’s Civil Air Transport for use in supporting guerrilla warfare against Communist China.[44] Civil Air Transport later became CIA’s airline Air America.

In 1947 the CIA was created as a replacement for OSS, and SSU was transferred to the new CIA. At the start of the Korean War in 1950 Helliwell was the CIA’s chief desk officer for the Far East—in charge of all CIA operations in the Far East. In 1953-54 he was involved in CIA covert operations against Guatemala. After a 1954 report to the Eisenhower administration that the CIA’s Bangkok station was one of the largest opium emporiums in the Far East, Helliwell resigned from the CIA and returned to Florida. There he was an insurance company executive and served as the Royal Thai Consul in Miami—and of course still worked secretly for the CIA.

After Fidel Castro took over Cuba in 1959, the CIA organized the Bay of Pigs invasion. Helliwell served as the financial chief at JM/WAVE (near Miami), the main facility for CIA’s anti-Castro operations. Santo Trafficante, Jr., the Mafia leader who ran the western end of the French Connection, moved his drug-smuggling operation from Havana to Tampa, Florida.[45] The CIA procured mafia foot-soldiers (“volunteers”) from Trafficante to serve in the Bay of Pigs invasion, in return for CIA protection of Trafficante from prosecution by the Justice Department for his drug operation.[46]

The CIA also arranged for Helliwell to re-organize Trafficante’s crude financial operations. He soon set up Mercantile Bank & Trust in the Bahamas—the world’s first off-shore drug bank—followed by Castle Bank & Trust, another CIA drug-bank in the Bahamas, both of which Helliwell largely ran. Both banks were used by Trafficante’s drug-smuggling organization and for CIA covert operations and proprietaries.

In the mid-1960s Helliwell helped Hmong leader Vang Pao, who headed the largest opium-exporting organization in southeast Asia, modernize his operation, including using portable heroin processors developed by the CIA’s Technical Services Division.[47]

During his years in Florida, Helliwell engaged in some activities that outwardly do not appear to be CIA-related. In 1952 and 1956 he served as chairman of the Florida branch of Citizens for Eisenhower, a Republican political group that supported General Eisenhower for president. And in 1965 he secretly negotiated, through a large number of “dummy” corporations (his specialty), the purchase of a large amount of land in central Florida for the Walt Disney Corporation, on which Disney World was later built. Helliwell also enabled the Disney Corporation to circumvent Florida tax and environmental regulations by devising the legal strategy of having Disney create two “dummy” municipalities, the City of Bay Lake and the City of Lake Buena Vista (both incorporated by the Florida state legislature in 1967), which were actually controlled by Disney.[48]

However, Disney was led to Helliwell’s services by the legal firm of William Donovan, who had run OSS during WWII, and there is little doubt that Helliwell’s efforts to get Eisenhower elected in 1952 were part of the VOSS (Veterans of OSS) campaign to get Eisenhower into the White House so that he could appoint Allen Dulles director of the CIA. So it seems that even Helliwell’s so-called “non-CIA-related” activities were in fact CIA-related.

In later years Helliwell set up several more off-shore drug-banks and similar outfits for CIA-connected drug-smuggling and covert operations, such as Underwriters Bank and the Bank of Perrine.

These banks also received money from (or laundered through) casinos, resorts, drug-smuggling rings, and off-shore banks, usually involving the Mafia (especially Meyer Lansky) or wealthy international financial figures. Helliwell also served as legal counsel for a number of banks used by the Mafia, including Miami National Bank. In 1976 the IRS began (separate) investigations of Castle Bank and Mercantile Bank. Both investigations were opposed by the CIA.

In summary, Helliwell was a major player in the CIA’s secret money game and was deeply involved in creating the CIA/international drug-trafficking connection. He died in December 1976.

21. The import of the Miami Report’s account of the riot.

The Miami Report’s account of how the riot began differs greatly from the version of events told by other sources. Other sources say that the riot began about 1 p.m. on Wednesday, was instigated by outsiders and “people new to the community,” peaked from about 1:30 to 3:30 p.m., and was not responded to by Miami police during those two hours. The Miami Report, created by Paul Helliwell, omits or changes all these things. Instead, the Miami Report maintains that the riot began about 7 p.m. and therefore omits all the events that other sources say happened between 1 and 7 p.m.

The Report’s Preface states that the Study Team encountered large discrepancies between the witness accounts and, therefore, they created an account that seemed best to them. Most significantly, the Study Team account omits testimony that the riot was started by outsiders and claims that it did not influence the Convention. (The former omission was likely to conceal some of the evidence about how the riot actually started.)

In light of the CIA’s campaign to influence the 1968 presidential election and Helliwell’s high-level career running sensitive CIA operations, it would appear likely that the CIA started the Liberty City riot, that the riot influenced the Republican Convention in the way that it was intended to, and that the Miami Report was crafted to cover up those two things.

22. The impact of the Liberty City riot.

The CIA apparently created the Liberty City riot in order to influence the Republican National Convention to choose Richard Nixon as the Republican candidate in the 1968 presidential election—which it succeeded in doing. But there was another result: the great damage done to Liberty City and its residents.

During the riot three Liberty City residents were killed, 32 persons were injured (taken to Jackson Memorial Hospital), many cars and much other property was destroyed, a large part of Liberty City’s main shopping and business district (62nd Street) was destroyed, and a large amount of money was spent by the City of Miami, Dade County, and the State of Florida in responding to the emergency.

In addition, the destruction of Liberty City’s main shopping and business district took away the livelihoods of many residents and placed a great burden on those residents to rebuild that part of their community once again into a successful shopping and business district, which it took quite a few years to do. The riot was a great injustice to the residents of Liberty City and there needs to be compensation and justice for them.

-

Theodore White, The Making of the President 1968 (New York: Atheneum, 1968), 238. ↑

-

David English, Divided They Stand (M. Joseph, 1969), 286. ↑

-

NW 62nd St. is the main east-west street in Liberty City and is today called Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. In 1968 it was one of Liberty City’s best shopping areas, lined with attractive shops and stores. ↑

-

Gov. George Wallace of Alabama was a well-known segregationist who opposed the Civil Rights Movement. In his 1963 gubernatorial inauguration speech, Wallace proclaimed his support for “segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” He symbolized white racism in America. In 1968 Wallace ran for president on his own American Independent Party; in July of that year, he visited Miami to promote his presidential campaign. Throughout the year, Wallace was getting about 20% in the polls nationally, but on election day, he only received about 10% of the national vote. In November Wallace won in five states in the Deep South: Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas. ↑

-

Miami Times, August 16, 1968, 2. ↑

-

Unless otherwise noted, citations of the Miami News herein refer to the Metropolitan Edition (published in the morning) rather than to the Blue Streak Final Edition (published in the evening). ↑

-

Miami News, August 8, 1968, A11. The parenthesized words (white man) were in the Miami News article. ↑

-

Miami Herald, August 8, 1968, A2. ↑

-

The Miami Herald had reported the event briefly the previous day (Thursday, August 8, 1968, A2) without saying that the car had George Wallace bumper stickers or that this incident sparked the ensuing riot. It said:

One man was injured in an accident when his car struck a delivery truck at an intersection in the trouble area and he fled to the Liberty Bar and Package Store nearby at 1492 NW 62nd St. Sylvester Perry, the bar manager, said he “sent the man out my back door and two of my customers took him to a hospital.” ↑

-

The “Vote Power” voter registration meeting was held in the meeting-hall on the first-floor of the three-story building at 1675 NW 62nd Street and began at 10 a.m. on Wednesday. The “Vote Power” mass rally was held on the street outside the building and began at 1 p.m. Wednesday. The writers of the Miami Herald article appear to have confused the two events and thought that Mike Tanner and the other Herald reporters were expelled from the rally rather than from the meeting-hall, and that this happened about 10 a.m. rather than about 1 p.m. ↑

-

The Miami News reported that, “after a rock smashed a window of the mayor’s car, Miami police…set up a command post at Manor Park, NW 50th Street and 13th Avenue” (August 8, 1968, A11). ↑

-

Miami Herald, August 9, 1968, A2. ↑

-

The “Final Report of the Grand Jury” for the Spring 1968 term of the Eleventh Judicial Circuit Court of Florida (Dade County), filed on November 19, 1968, states that “our investigation revealed that during the most violent part of the disturbance for a period of one hour, officials at the command post were unable to contact the City Manager, who is the only municipal officer with authority to request the Governor to send in the National Guard” (p. 7). The juncture of this statement with the Miami Herald’s account of the Mayor’s unsuccessful calls to the City Manager, means that one hour somewhere between 1:30 and 3:30 p.m. Wednesday was “the most violent part of the disturbance.”

According to the 1967-1968 Report of Florida’s Adjutant General (Maj. Gen. Henry McMillan) to Gov. Claude Kirk, on August 7 local National Guard units assembled at their armories as a precaution in connection with the Republican National Convention. This means they could have responded quickly to the Liberty City riot if they had been requested by the City Manager. But Miami authorities did not make that request until mid-afternoon on August 8 (1967-1968 Report, pp. 18-19). According to a Dade County Public Safety Deptartment document, the request for National Guard assistance was made by Dade County Sheriff E. Wilson Purdy at 3:45 p.m. on Thursday, August 8. ↑

-

Miami News, August 8, 1968 (Blue Streak Final Edition), A11. ↑

-

Miami Report, 9, which also states: “A telephone emergency call box on the corner of N.W. 17th Avenue and 62nd Street was used by the officers to submit reports to their superiors.” ↑

-

Miami Herald, August 9, 1968,2A. ↑

-

English, Divided They Stand, 296. ↑

-

Miami News, Aug. 8, 1968, A11. ↑

-

Miami News, Aug. 9, 1968, A7. ↑

-

Miami Herald, August 8, 1968, A1. ↑

-

Miami Herald, August 8, 1968, A1. ↑

-

Miami Report, 9. ↑

-

Miami Report, vii. ↑

-

Miami News, Aug. 8, 1968, 11. ↑

-

Miami News, August 7, 1968, A1. ↑

-

Miami Herald, August 9, 1968, A1. ↑

-

Those killed during the riot included E. Jest Cleveland, 45, of 329 NW 22nd St., Apt. 9 (who was shot at midnight on the porch of his apartment); John J. Austin, 37, of 1423 NW 68th Terrace (said by police to have been a sniper, although those who found his body said he was unarmed); and Moses Cannon, 27 (unarmed), 1361 NW 61st St., Apt. 11. Austin and Cannon were killed in a shoot-out between police and a sniper (who had fired on a police car) in an alley at 1431 NW 62nd St., although there was no return fire from the sniper once the police started shooting and there appears to be no evidence that either Austin or Cannon was the sniper. The Miami police said that a fourth person killed in Liberty City during the period when the riot happened appeared to have been a crime victim. The obituaries of John Austin and Moses Cannon appeared in the Miami Times on August 16, 1968, 23. ↑

-

On August 9, 1968, the Miami Herald reported that “the emergency room at Jackson Memorial Hospital treated 32 persons for injuries, including six for gunshot wounds” (p. A2). That same day (August 9, 1968) the Miami News listed 18 of those who were injured on August 8, with most of their home addresses (p. A7). In addition, the City of Miami sent medical teams to the affected areas to treat victims of tear gas. ↑

-

Miami Report, v-vi. ↑

-

Miami Report, viii. ↑

-

Miami Report, vii. ↑

-

Miami Report, 6. In its Summary the Miami Report states: “The fact that the Republican National Convention was taking place during the week of August 5th, at Miami Beach, some seven miles away from Liberty City, played only an incidental part in the course of the disturbances. The disturbances involved no articulated political or ideological issues such as the Presidential campaign, Viet Nam or the draft” (p. vii). ↑

-

Miami Report, viii. ↑

-

Miami Report, 2. Chief Headley took a tough approach to race relations and alleged “Black crime.” On August 8, 1969, the Daytona Beach Morning Journal reported that, in 1967, Headley said that “community relations programs are not affecting criminal activity of the hard core criminal element” and that such programs were “interpreted by some as a form of appeasement.” In December 1967, in response to three murders committed during robberies in Liberty City on the weekend before Christmas, Chief Headley started a controversial “get tough” program to reduce crime in Miami’s largest Black neighborhood, Liberty City. Beginning on December 26, police patrols in Liberty City were armed with shotguns and dogs. “Felons will learn that they can’t be bonded out of the morgue,” Headley said. “We don’t mind being accused of police brutality. They haven’t seen anything yet.” In his statement announcing the crackdown Headley singled out “young black thugs” who take advantage of the civil rights movement by committing crimes during demonstrations. Headley warned that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts,” a statement that was criticized by many civil rights leaders. Floyd McKissick, head of the Congress of Racial Equality, accused Chief Headley of setting up “a fascist state in Miami.” Liberty City’s newspaper The Miami Times demanded that Headley resign. Headley later said that his program had greatly reduced holdups and other violent crimes in Miami’s Black neighborhoods. He was away on vacation (in North Carolina) when the Liberty City Riot occurred. He died of a heart attack three months later (November 1968) at age 63. (Chicago Tribune, December 28, 1967, 2; July 6, 1968, 46; and November 11, 1968, 42.) ↑

-

Miami Report, 10. ↑

-

Miami Report, 11-12. ↑

-

Eric Tscheschlok, “Long Time Coming: Miami’s Liberty City Riot of 1968,” Florida Historical Quarterly (vol. 74, no. 4, Spring 1996, 440-460), confirms 1 p.m. as the start-time for the “Vote Power” rally but gives no times for the subsequent disturbances/riot on NW 62nd Street (p. 444). Mr. Tscheschlok used both the Miami Herald and the Miami Report as major sources, and it is possible that he omitted stating the times that the riot started and when it expanded because of the conflict between these two sources. ↑

-

Miami Report, vii. ↑

-

Some of the Study Team’s staff were members/employees of Helliwell’s law firm. ↑

-

E. Howard Hunt, Undercover: Memoirs of an American Secret Agent (New York: Berkeley Publishing Corp., 1974), 42. ↑

-

In 1943, when she was a 21-year-old working for the Office of War Information, Nancy Bean allegedly smuggled in her underwear nuclear secrets to Niels Bohr. Her first husband was Theodore White, who grew close to JFK while he was writing The Making of the President 1960. Thereafter the Whites were part of the Kennedy inner circle. In 1965 she wrote Meet John F. Kennedy, a book for young readers. Her daughter from her first marriage, Heyden, married Charles Nicholas Rostow, the deputy legal adviser to the National Security Council. He was the son of Eugene V. Rostow, who was the number-three man at the State Department during LBJ’s presidency, and the nephew of Walt Rostow, who was LBJ’s national security adviser. Nancy White Hector died in 2007. ↑

-

Major sources for Helliwell include G.J.A. O’Toole, Encyclopedia of American Intelligence and Espionage (Facts on File, 1988); Peter Dale Scott, American War Machine (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014); Jonathan Kwitny, The Crimes of Patriots (New York: W.W. Norton, 1987); and Alan A. Block, Masters of Paradise: Organized Crime and the Internal Revenue Service in the Bahamas (New York: Routeledge, 1991), regarding Helliwell’s organization of offshore banks. Dr. Alan Block is professor in the Administration of Justice Department at Penn State University. Dr. Peter Dale Scott teaches at UC Berkeley. Scott’s 1991 work Cocaine Politics, co-written with Jonathan Marshall, is the major in-depth account of CIA-Contra cocaine-trafficking to America. Jonathan Kwitny was then the Wall Street Journal’s main reporter for the Far East. His 1987 work The Crimes of Patriots is the major account of the Nugan-Hand drug-bank scandal. ↑

-

Richard Michael Gibson and Wen-hua Chen, The Secret Army: Chiang Kai-shek and the Drug Warlords of the Golden Triangle (New York: Wiley, 2011), chapter 4. ↑

-

Alfred W. McCoy, The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade (New York: Lawrence Hill Books, 1991), pp. 167-68. Dr. McCoy is professor of Southeast Asian history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The 1972 edition of The Politics of Heroin is a classic work that first made public the CIA’s role in massively expanding the international drug trade. ↑

-

The French Connection—basically, Turkish opium shipped to Marseilles, where it was processed into heroin, then shipped to Havana for distribution to American cities on the East Coast—was created in the late 1940s by “Lucky” Luciano. ↑

-

In 1954 the CIA reached an agreement with the Justice Department that gave the Agency the right to block a prosecution or keep a crime secret in the name of “national security” See Mark Lane, Plausible Denial: Was the CIA Involved in the Assassination of JFK (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1991), 113-14. ↑

-

Dennis Dayle, a top DEA investigator, stated that, “in my 30-year history in the Drug Enforcement Agency and related agencies, the major targets of my investigations almost invariably turned out to be working for the CIA.” See Peter Dale Scott and Jonathan Marshall, Cocaine Politics: Drugs, Armies and the CIA in Central America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), x-xi. ↑

-

On Helliwell and Disney, see T.D. Allman, Finding Florida: The True History of the Sunshine State (New York: Grove Press, 2013). In addition, at least two of the Miami Report Study Team’s staffers, Ralph C. Datillio and Mrs. Terry Cueto, were members of Helliwell’s Miami law firm, Helliwell, Melrose & DeWolf. Mrs. Cueto (Maria Theresa Cueto) was also involved in many of Helliwell’s Mafia-connected financial activities in the Bahamas. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Robert Aldridge was raised as an “Army brat” (his father was a POW under the Japanese for 3½ years during WWII) and graduated from the University of Central Florida in 1979 (B.A. History and Political Science). He now lives in Los Angeles, where he formerly worked for the Abstract Expressionist artist Sam Francis.

In the early 1990s, being outraged at the CIA’s involvement in the Contras’ cocaine-trafficking, he began researching the CIA’s larger role in international drug-trafficking. This soon expanded to include the CIA’s domestic activities (common cast of characters). In 1999 he published “The Lost Ending of the Didache” (Vigiliae Christianae, Feb. 1999), which revealed the missing ending of a very early Christian writing.

In 2011 he wrote The First Gospel, which tells the story of the first Christian writing, the Aramaic gospel Melê d-Māran. In 2015 he wrote The Aramaic Hypothesis, which makes corrections to the text of the four gospels based on the Aramaic substratum. In 2018 he created the DVD The Story of Illegal Drugs in America to encourage young people not to use illegal drugs.

Robert can be reached at sgc.radio2@gmail.com.

There are instances in this article where the N word is used as indicted in the following. The editor needs to correct this: Here are three examples but there were more than three instances.

A brick struck Officer Joseph Mullen in the back of the head. Major Adam Klinkowski grasped the injured officer and pushed him toward another squad car – already occupied by two N_____ prisoners.

Six hundred Florida National Guard troops moved into Miami’s violence-torn Liberty City N_____ district Thursday evening as gunfire killed three men during a day and night of looting, firebombing and racial disorders

The Rev. Theodore Gibson, a prominent N____ churchman, said bitterly, “They were too late, just too late