“‘All-out war’ suddenly broke out in Sudan, U.S. traveler says,” read the title of an NBC news report published on April 18.

Eight days later, The New York Times published an article headlined, “‘War Has Just Erupted’: Reporting on the Conflict in Sudan.”

Centered around interviewing the Times’s chief Africa correspondent, Declan Walsh, the piece first asked how did his work on the conflict begin? “On that Saturday morning at about 10:30,” Walsh responded. “I received a text message from a friend of mine, a Sudanese guy I had worked with during the revolution in 2019.”

That friend had sent Walsh an “audio clip of the sound of gunfire ringing out in the streets outside his house,” explaining that “there was a paramilitary camp about 400 meters from where he was and that it was being shelled…‘Hey Declan,’” the friend continued, “‘war has just erupted in Khartoum,’” the Sudanese capital. Hearing the news, it became Walsh’s “first inkling that something very serious was happening.”

Based on these and similar mainstream Western media accounts, it was as if, on one sunny day, the Sudanese military ruler and army chief, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and his entourage were hanging out, having a laugh and lunch with his deputy and head of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemeti) and his bodyguards at a restaurant in Khartoum.

Less than 24 hours later, both parties, in the blink of an eye, struck with irreconcilable hatred and enmity toward each other, would deploy military airplanes, helicopters, tanks and soldiers onto the capital, firing upon each other at will. As reckless, mindless, and “sudden” a conflict could unfold, at least 460 people were killed during the first 11 days of fighting, according to Sudan’s Ministry of Health. The actual number of people who have lost their lives is expected to be much higher.

Unlike Hemeti, al-Burhan is also the head of the Transitional Sovereignty Council, the original institution tasked with facilitating the transfer of power from military rule to a civilian government.

However, almost four years after the toppling of former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, who is currently being held at a military hospital in Khartoum, civilian rule has yet to be implemented in Sudan.

Al-Bashir is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for alleged war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in Darfur; however, the Sudanese have declined requests to hand over the former head of state.

Al-Burhan, meanwhile, is backed by Egypt’s brutal dictator, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and layers close to the military that have long controlled Sudan’s sprawling military-industrial complex. He is reportedly supportive of the U.S. and the European powers in the U.S./NATO war against Russia in Ukraine, and it would not be surprising if we learn that he is receiving some form of U.S. military or covert CIA support.

Searching for Answers

Might this conflict, what some are referring to as an abrupt civil war, have something to do with Sudan’s partition—the solution reached for the religious and ethnic divides prompting so much bloodshed in Darfur? I asked myself. Might the roots of the conflict date back even further? If my first line of query is true, then a not-so-sudden gap extends between South Sudan’s statehood commemorations and the current fighting.

South Sudan was created in July 2009 after a referendum agreed to in a 2005 peace agreement that ended the war between northern and southern Sudan. The U.S. helped midwife the creation of South Sudan as part of a plan to take control of the country’s oil—northern Sudan’s leader, Omar al-Bashir, was pro-Chinese and targeted by the Bush administration for regime change. For years the U.S. had supported—including via proxy through Uganda—the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), which had fought a war against northern forces.

The larger geostrategic designs of the United States and less than saintly behavior of the SPLA—which carried out terrorist atrocities along with the Sudanese army during Sudan’s civil war—is largely underplayed, if not outright suppressed, in most mainstream media reporting.

A simple Google search on the birth of South Sudan comes up with statements of President Obama who, for example, said on July 9, 2011: “I am proud to declare that the United States formally recognizes the Republic of South Sudan as a sovereign and independent state upon this day, July 9, 2011. Today is a reminder that after the darkness of war, the light of a new dawn is possible.”

Nice words but the new dawn did not bring much light as the new dawn brought renewed war in South Sudan as various different political factions and ethnic groups contended for political power.

Obama’s pronouncement, furthermore, masked U.S. imperial designs; it came at a time that Obama was expanding AFRICOM on the continent and just four months after his administration and NATO unleashed a torrent of air strikes upon Libya.[1]

These strikes culminated in the death of Libya’s leader, Muammar Gaddafi and paved the way for religious fanatics to parade around what was previously one of the most progressive and stable countries in Africa. In fact, their presence had spread far and wide across the Sahel.

Conceding that U.S. aggression against the North African country marked his biggest mistake as president—“failing to plan for the day after, what I think was the right thing to do in intervening in Libya”—the consequences of that misadventure are still being played on the newsreel: ISIS and other terrorist groups’ metastasis and advance in Libya, Chad, Central African Republic, Mali, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, and elsewhere; the free flow of weapons from and through Libya; waves of migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean into Europe; and flourishing slave markets sprawled across Libya.

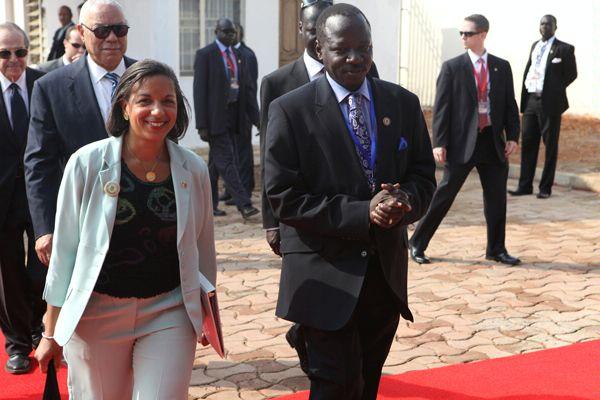

Among the crowd gathered in Juba, capital of South Sudan, to celebrate the birth of their new country was U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Susan Rice. “Our support for the cause of peace for the Sudanese people has long been bipartisan and deep and it will continue to be,” she said. “We helped broker the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that led us here today, and we will continue to watch over it—and the future to come.”

Apart from what had just happened in neighboring Libya, it was as if signatories to the Berlin Conference had hopped into a time machine. Their destination? To connect with Obama and Rice, ostensibly adopting a diversity, inclusion, and equity (DIE…not DEI) mandate in further slicing and dicing Africa.

Divide, Weaken, Conquer

Rich in oil and gold, Sudan was, prior to its partition, the largest country on the African continent. With the exception of Hong Kong and Macao, China, despite its backwardness and susceptibility at the time, warded off attempts to carve its territory into tiny states.

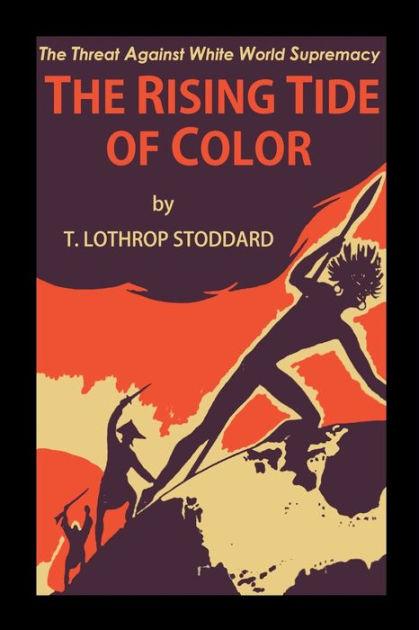

Harvard graduate and equally distinguished KKK and American Eugenics Society member Lothrop Stoddard probably said it best in the title of his 1920 literary classic and New York Times editorial favorite, The Rising Tide of Color: The Threat Against White World-Supremacy. Poignantly, he wrote, “Toward the close of the nineteenth century the world had been earnestly discussing the ‘break-up’ of China…The huge empire, with its 400,000,000 people, one-fourth the entire human race, seemed at that time plunged in so hopeless a lethargy as to be foredoomed to speedy ruin. About the apparently moribund carcass, the eagles of the earth were already gathered, planning a ‘partition of China’ analogous to the recent partition of Africa. The partition of China, however, never came off.”

Seventy-plus years later, The New York Times Magazine reminded us that such outworn, primitive ideas remained rock-steady by publishing an article in 1993 by Paul Johnson titled: “Colonialism’s Back—and Not a Moment Too Soon.” The subhead read: “Let’s Face It: Some Countries are Just Not Fit to Govern Themselves.”

In 1991, two decades before Sudan’s partition and during the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), Khartoum became the residence of mujahideen leader Osama bin Laden. “I am a construction engineer and an agriculturalist,” he told Robert Fisk, reporting for The Independent. “If I had [terrorist] training camps here in Sudan, I couldn’t possibly do this job.”

In 1998, suspecting the production of chemical weapons for use by al-Qaeda, the U.S. military launched cruise missile attacks against Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum. The attack killed or wounded 11 people.

If U.S. officials’ pursuit of a grand strategy includes provoking problems in order to establish conditions and scenarios favorable to the cause of U.S. hegemony, then Sudan, like Libya, may be a prominent piece on their geo-political game-board.

While the urge to believe in sudden, out-of-the-blue military conflicts might be real, such contentious, deadly events are mostly, if not always scripted by Hollywood. If not, a second-best choice might be—as John Stockwell, Philip Agee and others who worked for the CIA inform—Western intelligence agencies.

A third choice, as reasonable as the previous two, might point to lackluster or inadequate Western media profiles in terms of how they manage covering the African continent. For example, recent and promising HIV vaccine trials taking place in Zambia are not making a splash in their headlines.

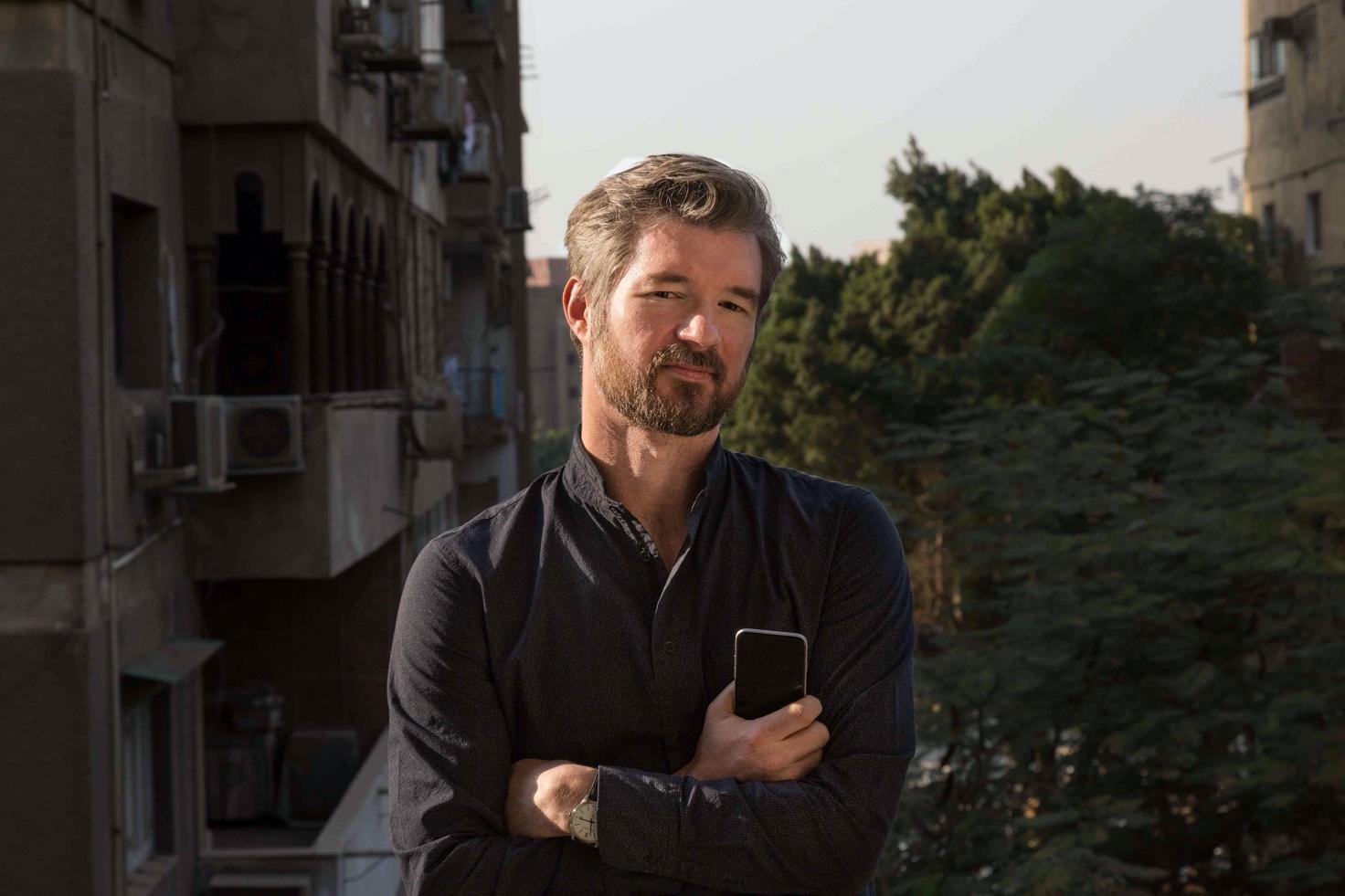

Reaching Out to Clint Nzala

Wanting more insight into events behind the deadly clashes in Sudan and related issues, I reached out to Clint Nzala. A media colleague based in Nairobi, Kenya, working for African Stream, an outlet producing news about the continent and Pan-Africanism, he is no “expert.” From Zambia, Nzala once told me that, by and large, “experts” on African affairs, those pundits routinely welcomed on-air at the big name, legacy media firms, as well as an increasing number of alternative outlets, are Westerners. “They spend about two weeks in a hotel in Lusaka or what have you and, bam, they’re experts.”

For a bit more clarity to the crisis in Sudan, I turned off the television, turned down YouTube, and asked Nzala a few questions.

Interview

Julian Cola (JC): As the head of Sudan, al-Burhan seems to be more known. But give me a rundown of Hemeti, head of the RSF paramilitary.

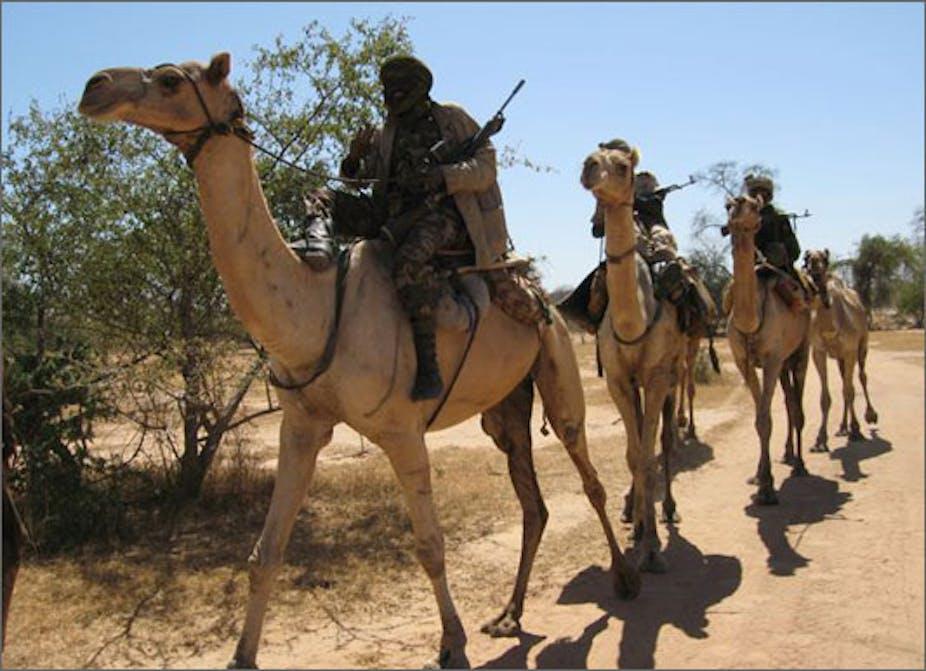

Clint Nzala (CN): To try to understand the foundation of the so-called RSF, these forces with Hemeti, they started as the famous Janjawid militia. During the civil war in Darfur, when al-Bashir [former Sudanese president] was fighting against Africans who were rebelling against the Arab government in Khartoum, he allowed private militias, individuals to set up militias to do his dirty work. These individuals were Arabs who set up militias to oppress, to clamp down on the Blacks. They were more brutal than the regular army. So the work which the army couldn’t do was handed over to these militias. These militias burned down villages. They poisoned wells so that those Africans in Darfur would not have access to water.

So that was Hemeti. He was a businessman from a tribe in the Darfur region. He started his business stealing camels in Sudan and Chad and then selling them in Libya. So he made a bit of a fortune and organized this militia, which was the most successful, the most brutal. Then, later on, his militia group was rewarded by al-Bashir, by almost regularizing the militia, the guys who were not getting salaries from the Sudanese Army. At one time it became a division of the Sudanese Army but was never fully integrated. Then, like all traitors, when those protests against al-Bashir started, the militia, initially, tried to help al-Bashir but when they saw that the tide was against al-Bashir, they switched and claimed to be on the side of the people. That’s how the Janjawid took part in that coup. All this time Hemeti has had political ambitions. So that’s the guy [Hemeti]. He started his career and made his name by killing people, massacring people in Darfur.

Then this general [al-Burhan] who is the head of the army, they put that civilian guy [Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf] there as a token position [Chairman of the Transitional Military Council—a position Awad Ibn Auf held for only one day in 2019]. But it was just a token position. The real power was with Hemeti and al-Burhan in the military. So now there seem to be some divisions between the two because they were eyeing the top spot.

JC: The U.S. government, during the Obama administration, supported and welcomed the partition of Sudan. Is there an influence, if not direct role between U.S. foreign policymakers and their allied countries, and the current conflict? If so, what’s the purpose?

CN: Here’s the issue, I think the division of Sudan into the north and the south wasn’t entirely externally pushed. There were definitely issues, the north being predominantly Black, Christian, English speaking, in addition to the indigenous languages. Then the north, being predominantly Arab, Muslim. So it created certain tensions which got exacerbated, especially towards the 1980s. So it was a bit inevitable, whether there was an external hand or not. That’s one thing. When you look at al-Burhan and Hemeti, literally, I don’t think there’s a good guy. All and all, the Sudanese people are paying the price. Al-Burhan and Hemeti are pressing their agenda. They just want power for themselves.

JC: Is China involved in the conflict?

CN: China has not played any role in this. To a large extent, this is a purely internal matter.

JC: Is Russia involved?

CN: From the look of things, Hemeti has been getting more support from Russia compared to what Burhan has received from the U.S. So it’s part of the West and Russia. There is some low-key ____ shit. Interestingly, Hemeti’s forces have also been exporting mercenaries to Yemen to fight against the Houthi fighters in Yemen. He has been fighting on the side of this coalition led by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the like.

JC: What about the now expired three-day brokered cease-fire to evacuate, primarily, foreign citizens holding Western passports? Does this conjure memories of the genocide in Rwanda? It seems even worse. One CNN article was titled: “People stranded in Sudan after Western diplomats flee without returning travel documents.” I thought diplomats were supposed to be trained to handle such situations and be the last people to leave.

CN: Unfortunately, it seems so and the thing that these Africans—I don’t know if I’d call them leaders—whenever they are fighting, they’re more concerned, of course they’d avoid—they wouldn’t want to cause any damage, inflict any casualties or deaths upon Westerners because they feel that it’ll have more consequences than if they kill someone from the DRC. So I think it all comes down to this issue where certain lives are valued more than others. They know that if they killed a Malawian they’d easily get away with it. But if they killed a German citizen or a U.S. citizen, they think they’ll probably end up at the ICC [International Criminal Court in The Hague].

JC: Similar to The New York Times’s chief Africa correspondent, Declan Walsh, you’re also based in Nairobi. Kenyan President William Ruto, recently stated, and I quote, “There is real danger that the escalation of hostilities in Sudan could implicate external, regional, and international actors and degenerate into a security and humanitarian crisis on a disastrous scale.” In what ways might Kenya and other regional [actors] be affected by the conflict in Sudan?

CN: The implications are that generally they are in the region, you’ve got a country like Kenya. To the north is Somalia, which is relatively stable. To the west is Uganda. It has become relatively stable right now. I think the military managed to neutralize the threat of this resistance army. Then Kenya took in a lot of refugees during the conflict in South Sudan, when South Sudan was fighting for independence from Sudan. So there are fears that if the war continues or it gets worse in Sudan, a lot of refugees are going to pour into Kenya. That’s one aspect, the humanitarian aspect. And just generally, Sudan is quite a big country not just in term of size but it is a big player in the region. And as you can see, Ethiopia already had the war in the Tigray. So another war in the region definitely spells trouble, instability. Now, flights coming in and out of Nairobi, if you’re flying from Europe or whatever, your flight time has been extended by an hour because they have to change routes. They have to avoid Sudan. So when they are leaving Kenyan airspace they have to go in the direction of the Middle East, then make a turn to avoid Sudanese air space. So there’s just a lot in ways the region gets affected.

JC: Is there a lack of credibility when it comes to mainstream and increasingly more alternative Western media coverage concerning Sudan in general and Africa in particular? What can you say about The New York Times, one of the largest, most respected and influential media outlets in the world—so I am told—relying on an African correspondent whose “first inkling that something very serious was happening” in Sudan came after the guns had sounded?

CN: They should definitely get fired. This has been building up before the conflict broke out. There were indicators that it was a matter of time. It was coming. And it was an issue of when is it going to start. If you’re going to have these African experts who are not from the region…you wonder when someone…I’m not saying non-Africans shouldn’t be covering these stories. But I feel that first, if you’re going to be a correspondent, I doubt if that correspondent even speaks Arabic. So it’s that issue. Maybe you’ll need a local. If you’re just going to hang around the swimming pool of your five-star hotel or live in a nice gated estate as a correspondent, sometime some information is most likely [going] to miss you. Sometimes the best source to get your information, you have to go to the local official office where the local people are there. Yeh, a few gossip flies around about certain topics. You won’t only get an indication that the conflict is growing when you hear the gunshots. So I think the signs had been there that the relationship between Hemeti and General Burhan were constantly drifting apart. And they were two very powerful individuals commanding thousands of men under their command, heavily armed men. So if they continued to be drifting apart one would have to say that it would end in the situation it has ended.

JC: One day you told me that you’d like to be a fixer. How would you fix the conflict in the Sudan?

CN: If I was to mediate…damn bruh…I mean, one Sudanese citizen said, “look, as ordinary citizens, we got absolutely nothing to gain regardless of who’s going to win but we are paying the price with our blood which is being shed for something that doesn’t concern us.” It’s not even about trying to remove a bad dictator and people are benefitting. No, there’s zero. It would be tough. Generally, if you’re mediating…cease-fire. Finding a way of assuring both of them that they’re not losing, that their interests are protected. That’s what you want because none of them are willing to back down.

JC: Last week I listened to a news report. It said, and I quote, “HIV killed 650,000 people in 2021 and 14 million since its discovery, according to the most recent available data. The vast majority are women and unprotected adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa.” Tell us about the HIV vaccine trials in Zambia, what William Kilembe, the head medical research, and his colleagues call, “the killer-T-Cell vaccine strategy.”

CN: So that vaccine. That vaccine joins…there’s another one which they call PrEP. So PrEP, they call it Pre-exposure Prophylaxis. It is for people who are, maybe, engaged in behavior that put them at risk for contracting HIV. So, maybe sex workers. Some health workers. And even people who have partners who are HIV-positive. They themselves are negative. So they have to take PREP before they get exposed to the virus as a way of prevention. It is an addition to the other methods such as condoms and the like.

So there has been a trial which has been going on. PrEP, you take pills, some sort of pills between one and three days before you encountered someone with HIV, which was cumbersome. The new one is an injection, which if you take one it’s like valid for a month. It lasts during the entire month and after taking it keeps you protected.

[Note: The killer-T-Cell Strategy aims to simulate and enhance t-cells, strengthening the immune system in its fight against the HIV virus]

-

For an overview of Obama’s neocolonial foreign policy in Africa, see Jeremy Kuzmarov, Obama’s Unending Wars: Fronting the Foreign Policy of the Permanent Warfare State (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2019). ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com