His case, along with that of the Italian Red Brigades, points to double standards in War on Terror going back to the 1970s

In August 1994, Carlos the Jackal was arrested in Khartoum, Sudan, after a long sting operation by the CIA, and he was subsequently tried and convicted on murder charges.

The operation seemed like a great success for the CIA. However, according to Ivan de Lignières, a top French intelligence operative, Carlos could have been apprehended almost 20 years earlier—before he carried out a wave of deadly bombings in France in the early 1980s.

De Lignières said that men under his command had identified the Jackal but could not act because they knew that he was “under surveillance by Algerian and Israeli intelligence services.”

“The light was always red for Carlos,” a livid de Lignières explained years later, “because of the Israelis. The latter appeared to protect him. Carlos had been the poster boy to discredit the Arabs and beef up the case of Israel. Any time we got close to [Carlos], we would see [the Israelis] around the corner.”[1]

Carlos the Jackal’s case is an excellent example of Western governments’ manipulation of terrorism and complicity in it—something that has begun to receive growing scholarly attention and is becoming better known.

Due to the extreme sensitivity of the subject, the literature on the topic is understandably relatively limited, but it has already produced considerable achievements.[2]

Historical, criminal and independent investigations, spanning the last two decades in particular, have improved our understanding of how government actors may manipulate terrorism for political purposes.

Two case studies may deserve attention in the U.S., because the relatively recent, sensitive findings in both are largely unknown in the Anglophone world: that of the Venezuelan terrorist Carlos “the Jackal”, and the Italian Red Brigades, a “left-wing” leaning, radical terror group.

As the most significant investigative developments took place essentially in France and Italy, English material on either case is, in fact, quite scant.

Both cases are better understood in the context of the current state of research and understanding of “counterterrorism” operations, which they significantly contribute to enrich.

Tracking down “the Jackal”

It was August 14, 1994, in the Sudan capital, Khartoum. At 3:00 a.m., the unusual Venezuelan resident was abruptly awakened and pinned down to his bed.

A special operation run by French operatives, building on the decisive cooperation of U.S. special forces, had finally captured the Jackal.

He had been one of the most wanted fugitives for more than two decades.

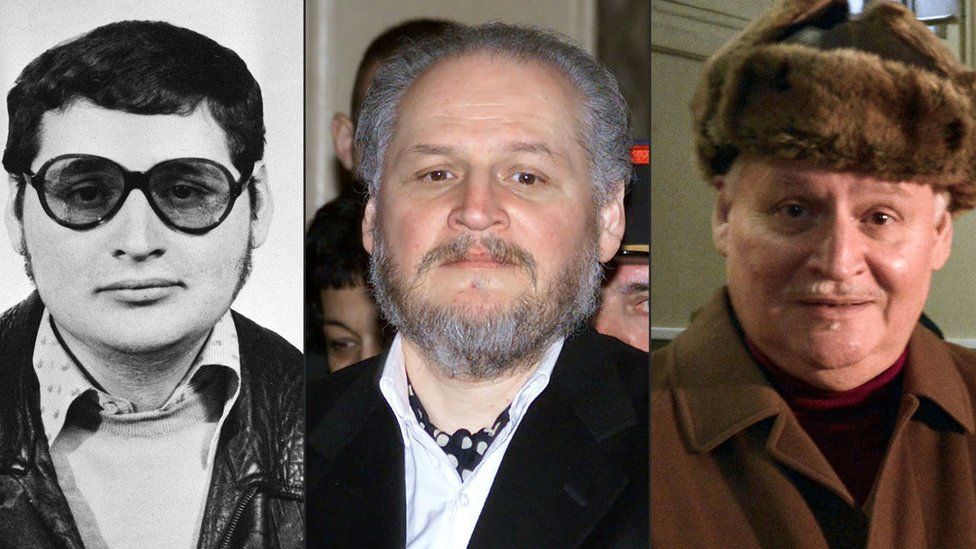

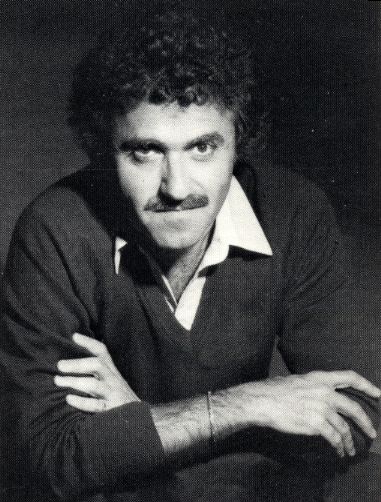

Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, better known to the world as “Carlos the Jackal,” or simply Carlos, was born into an affluent Venezuelan family in 1949.

His father, a wealthy, well-connected lawyer, was a radical Marxist.

After an unremarkable academic path in London and at the Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow, Carlos joined the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), where he pursued his revolutionary training.

It was in service of the PFLP that Sánchez executed his most well-known operations.

Carlos was one of the most notorious political terrorists of his time, with the most “spectacular” exploits taking place in the 1970s.

He is probably most remembered for the attack he orchestrated against the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

On December 21, 1975, Carlos and five associates took hostage a group of OPEC representatives holding a meeting in Vienna. They killed two security guards and a Libyan economist and detained more than 60 others. Carlos and his team subsequently obtained an aircraft and, after releasing some of the hostages, they flew the remaining 42 on an adventurous journey that ended in Algiers.

While the most flamboyant, that was just one of the many terrorist actions that spanned more than a decade.

The Jackal, largely marginalized and abandoned by his mentors with the decline of the Cold War, was finally captured in a “joint” operation of U.S. and French special forces.[3]

U.S. operatives had been able to monitor the movements of Carlos in Sudan and turned over their findings to French intelligence, which was able to get to Carlos and spirit him away from the country.

He was then tried in France, where he received multiple life sentences. He remains in prison.

Carlos, a French obsession

Since as far back as 1974, when he was suspected to have orchestrated his first terrorist operations against French targets, Paris was especially involved in the pursuit of Carlos.

He had participated in the planning of the September 13, 1974, occupation of the French embassy in The Hague, Netherlands, carried out by operatives of the Japanese Red Army.

As of June 1975, Carlos’s file was certainly very high on the French priority list. The Jackal was then accused of murdering two French officers of the DST, then the most prominent domestic law enforcement and intelligence service in France, approximately equivalent to the U.S. FBI.

Rigorous inquiries, performed by several investigative journalists, have uncovered a number of highly sensitive operations planned by Paris against the Venezuelan terrorist.

As it happens, several French presidents had ordered extreme action to be taken against the “Jackal.”

To be true, the official narrative of the assumed “chase of the Jackal,” as divulged reflexively by the mainstream media, has always been particularly problematic.

Sánchez, while ostensibly on the target list of most professional intelligence services covering half the world, was hardly in a position to evade detection and capture for such a long time (approximately 20 years).

Certainly, Carlos benefited from the protection of several countries, especially in the Middle East and North Africa, which were not sympathetic to Western security interests.

Yet, he also traveled freely and extensively in Europe, South America and elsewhere in the West, and he even enjoyed the luxury, under the circumstances, of spending vacation time in popular resorts (such as the Hotel Eden Beach in Malta).

The Carlos affair smacks of what certain scholarship described as “capability gap-driven” implausible, if not impossible outcome.[4]

Its inherent flaws aside, recent findings challenge directly the claim that more than 20 years of unsuccessful efforts to track Carlos were simply due to either negligence or “bad luck.”

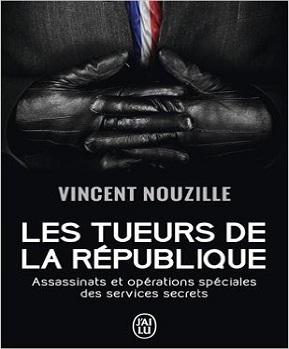

One investigative book that deserves special attention is Les Tueurs de la République, by Vincent Nouzille.[5]

Nouzille, a very respected investigative journalist in France, has extensive experience reporting on covert activities of French intelligence services, and has published extensively on the topic.

Les Tueurs de la République is an in-depth, fascinating, even when troubling, look into more than 60 years of covert operations, most notably executive actions, of French special forces.

Drawing and expanding on the best secondary literature, Nouzille fleshes out its research with fresh disclosures from top-level intelligence officers, including operatives who were intimately involved in the hunt for Carlos.

The most valuable contribution of this work is to provide an organic, updated account, providing an improved understanding of relatively known, yet not entirely appreciated, facts of terrorism.

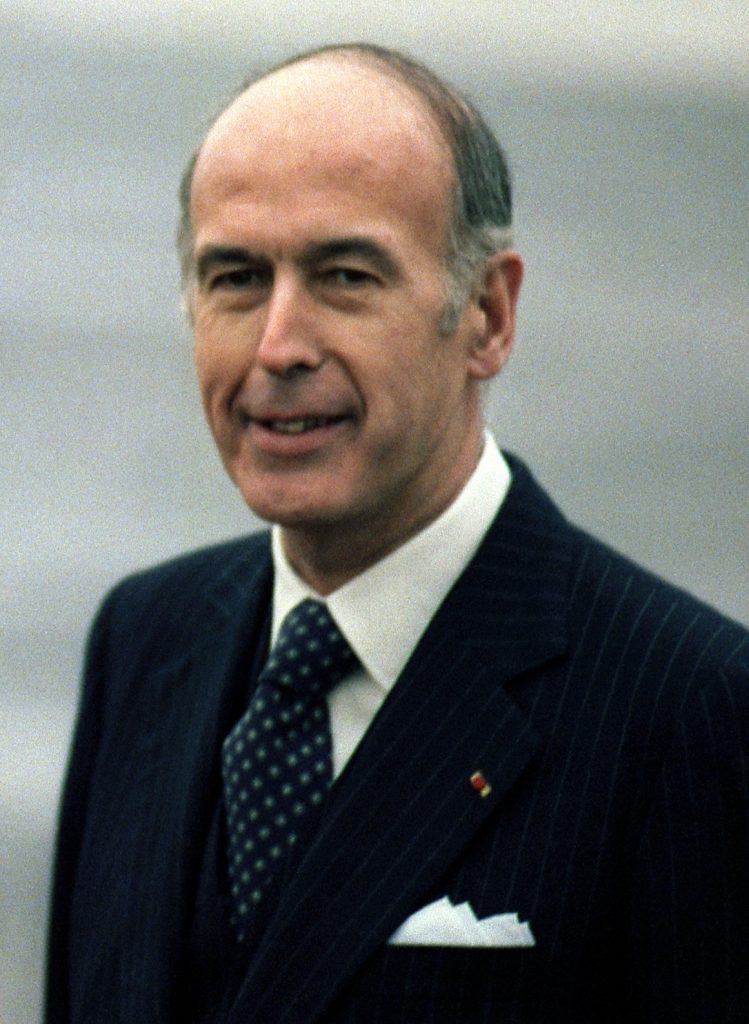

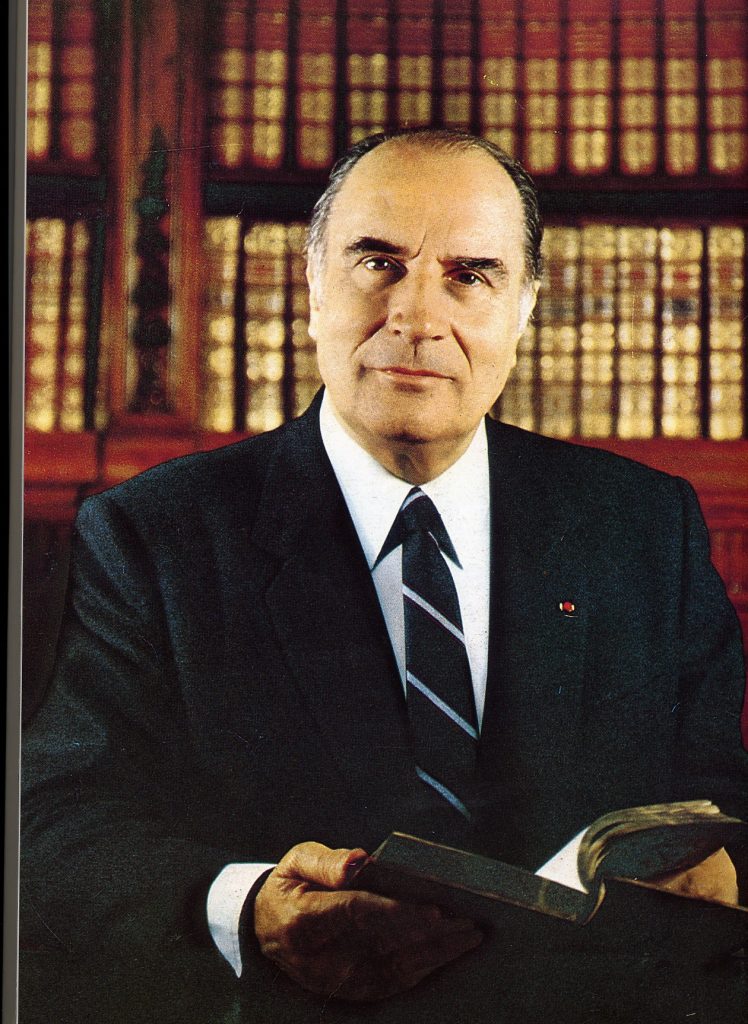

First, the intelligence sources of the French author confirm that Presidents Giscard d’Estaing (despite repeated public denials) and François Mitterrand ordered “neutralization,” read assassination operations, against Carlos the Jackal.

Sensitive operations to kidnap and or “neutralize” Carlos had been implemented since 1975.

A special squad was first dispatched to Algiers. The terrorist had taken shelter in the Algerian capital following the spectacular operation against OPEC representatives in Vienna.

It is important to note that this original mission was headed by a very skilled professional, Philippe Rondot, a future general and specialist of the Middle East (his father was also a high-profile intelligence officer).

Rondot would never cease to go after Carlos and was the officer in charge of the Sudan operation, where the terrorist was ultimately apprehended.

However, the mission in Algiers could not be accomplished.

Reportedly, a kidnapping in Algerian territory could ignite diplomatic tensions with local authorities, not exactly on the friendliest terms with Paris.

It was the beginning of quite an impressive series of presumably unsuccessful efforts.

A recurring fact, in the narrative reconstructed by the investigations, is that French special operatives had tracked Carlos plenty of times but then, for one reason or another, the ultimate go-ahead for carrying out the operation never came.

“We had received the order to eliminate Carlos. We had detected his location several times, including once in Algiers” recalled Alexandre de Marenches, legendary director of the SDECE, the French foreign intelligence service.[6]

Significant efforts were also undertaken under the presidency of François Mitterrand.

The socialist President authorized “extreme prejudice” operations against the Jackal.[7]

The intelligence sources interviewed by Nouzille make clear that Mitterrand had limited such executive action orders to just two instances—denying the same option in any other case—of Carlos and Abu Nidal, another well-known terrorist.

That is an authoritative confirmation of how sensitive, yet also how crucial, the elimination of Carlos was regarded.

They also reveal that in doing so, “Mitterrand had actually re-enacted the same directives issued by d’Estaing,” before adding, not so cryptically, that those orders “were the only ones that were not ultimately implemented.”

To resume: Since at least 1975, Carlos was on the assassination list of some of the most professional and well-trained special forces in the world.

Yet, it would not be until 1994 that he was finally captured.

It was Ivan de Lignières, however, a close associate and friend of Philippe Rondot, who would make the most explosive claims.

Early in 1977, Rondot and de Lignières engineered a sophisticated operation to get Carlos in his Venezuelan hometown, San Cristobal.

They managed to infiltrate the entourage of the Jackal’s father, José Ramírez.

One of the ideas was to make Ramírez seriously ill, in order to prompt his son to visit and to then capture him.

The preparations went on for months. Posted in Colombia, near the border with Venezuela, Rondot and de Lignières waited for the final “green light” from Paris.

Yet, it was a cancel order that they received, only a few hours before the operation was to take place.

Many years later, de Lignières stated his belief that the failure to get Carlos was intentional, due to the opposition of parallel intelligence services. In the immediate surrounding area where they intended to carry out the Venezuelan operation, the French team had spotted a Mossad agent.

In 1976, during another attempt in Malta (where Carlos was a regular vacationer at the Hotel Eden Beach), Rondot had to abort the operation one more time. His operatives had identified and spotted Carlos, but they could not proceed because the French operatives knew that they were under surveillance by Algerian and Israeli intelligence services.

There is hardly any doubt that de Lignières’ claims, stunning as they may appear, should be taken very seriously, particularly with the benefit of hindsight.

De Lignières was a top-level intelligence officer, involved, quite evidently, in the most sensitive operations of French special forces.

The relationship between French and Israeli authorities is also highly sensitive and, due to the extreme seriousness of the charge, it is wildly implausible that such a high-level official would make it without solid grounds.

The thesis that Carlos profited from highly placed protection, beside his own “safe havens,” is by far the most convincing in itself and with the benefit of the current state of research and available information.

If one perplexity might be leveled against the statement of de Lignières, it is that it may be too focused on the Israeli side. It is not credible that France, only because of Israeli involvement, would cancel, repeatedly, exceptionally elaborate operations against such a sensitive target which, one must recall, had already killed two French intelligence officials. It may be more plausible to assume that France may have had its own agenda for not ultimately carrying out the neutralization plan.

Yet, if anything, it reinforces the conclusion that Carlos was, indeed, protected by government authorities.

Despite the disturbing nature of these revelations, the least one may say is that they have been overwhelmingly underreported, if at all.[8]

Alternative explanations, by which the inability to get Carlos was largely, if not entirely, due to diplomatic sensitivities (which Nouzille himself appears to endorse at times), do not hold up to scrutiny.

First, the record is clear in showing that, when a threat is deemed to be considerable enough, governments and professional intelligence services establish priorities, risking in such cases a diplomatic incident.

The very core subject of Les Tueurs de la République, after all, is the story of highly sensitive assassination operations.

Citing one of the most significant cases, Nouzille recalls the notorious killing of the exiled Cameroonian leader Félix-Roland Moumié, on October 15, 1960, in a fancy restaurant in Geneva, Switzerland (the “execution team” had poured thallium, a powerful poison, into Moumié’s glass).

French intelligence leaders, such as General Paul Aussaresses, admitted openly to their responsibility in this assassination, that they saw it as necessary to eliminate a dangerous “political extremist” in the African nation.

If the official narrative deserved any credit, carrying out an assassination in Switzerland would not be significantly more problematic, in diplomatic or operational terms, than executing a kidnapping in Venezuela.[9]

More importantly, scholarly, criminal and independent inquiries have now exposed a long and extensive pattern of government protection of or involvement with terrorism activities.

The more the historiographical process carries on, the more problematic the connection between government actors, through their intelligence arms, in particular, and terrorism groups, turns out to be.[10]

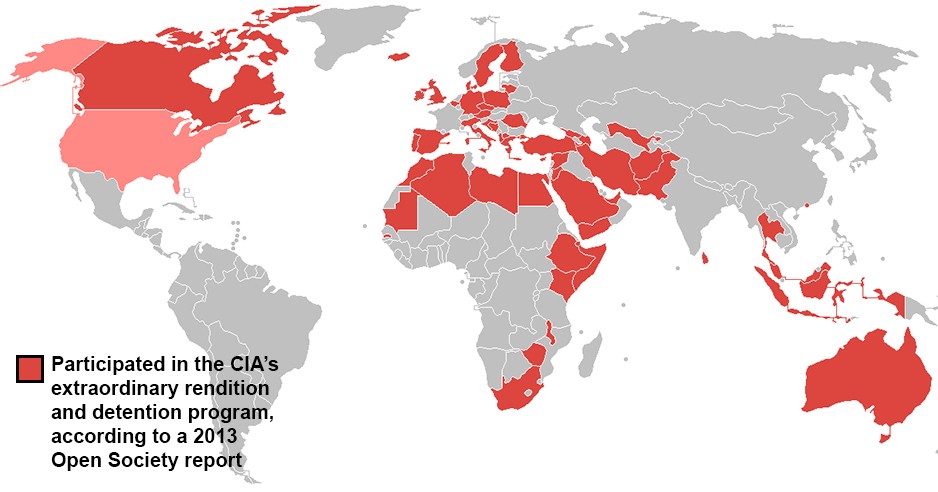

CAM itself has recently reported about the disturbing information concerning the links between U.S. intelligence and at least two of the 9/11 hijackers.

In Italy, parliamentary and judicial investigations, some of which are ongoing, have also exposed penetrating intervention in or manipulation of terrorism on the side of government agencies, both domestic and international.

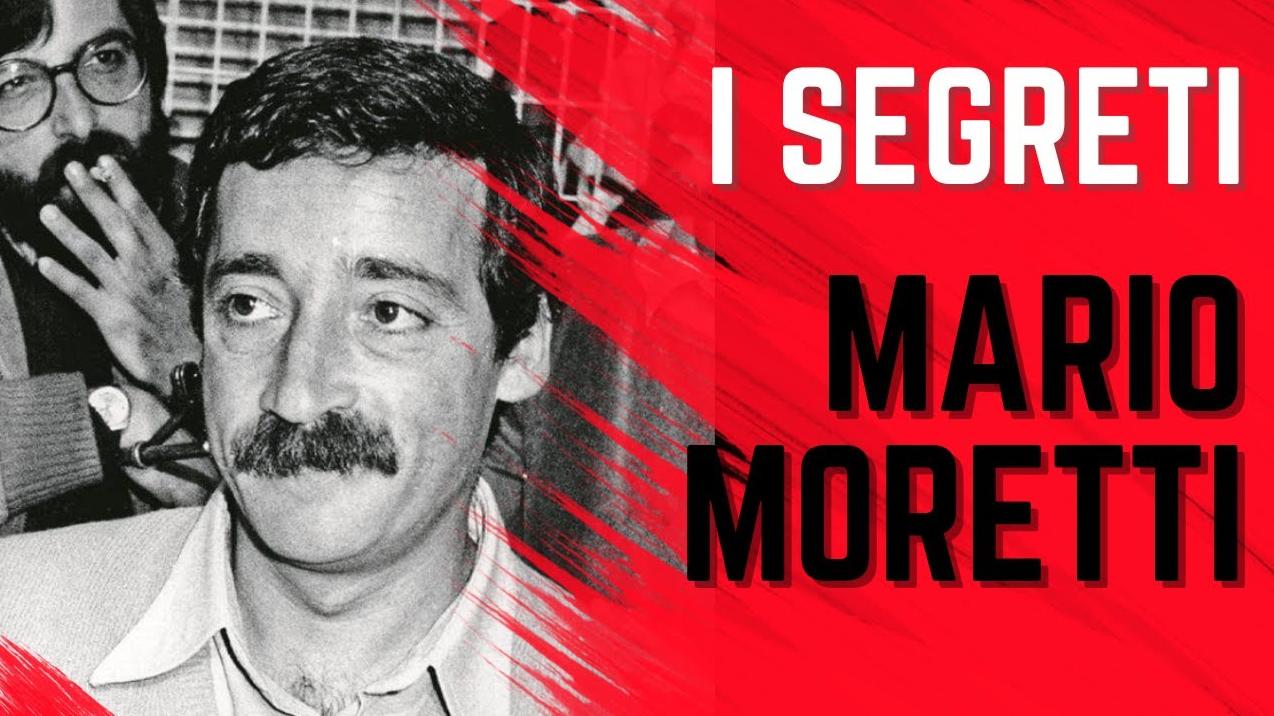

Mario Moretti, the Sphinx of the Red Brigades

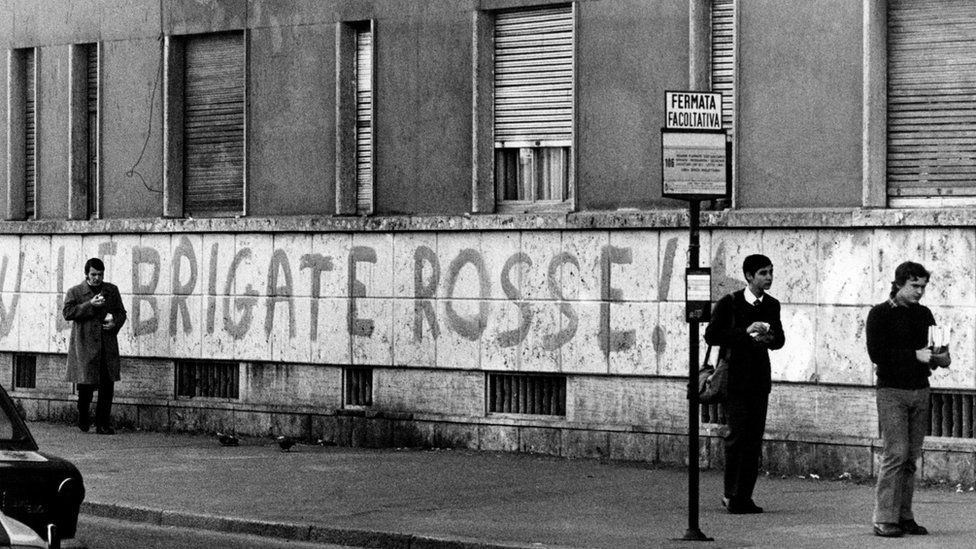

Some of the most sensitive disclosures concern the infamous group Brigate Rosse (“Red Brigades”).

The Red Brigades were assumed to be a radical left group, which engaged in extensive acts of terrorism in Italy throughout the 1970s.

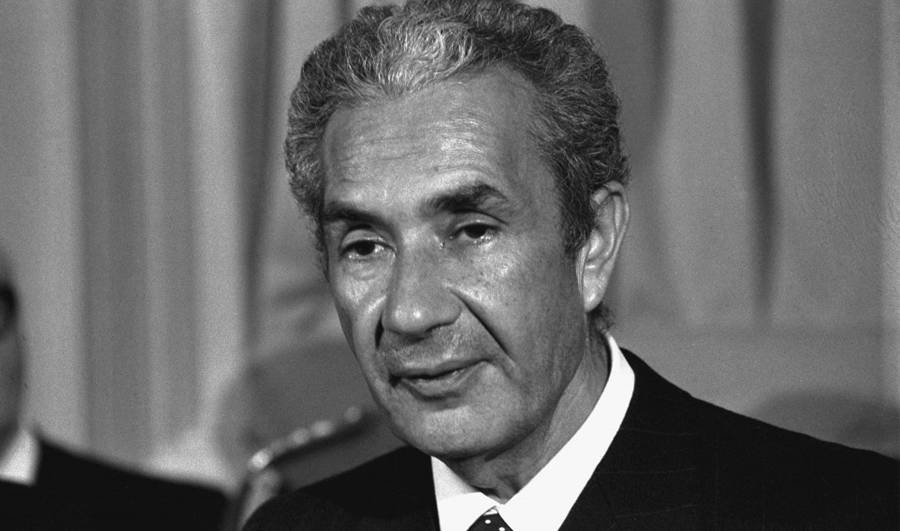

They are most notorious for allegedly carrying out the kidnapping of Aldo Moro, the prominent representative of the Italian Christian Democratic Party and two-time prime minister, in the spring of 1978.

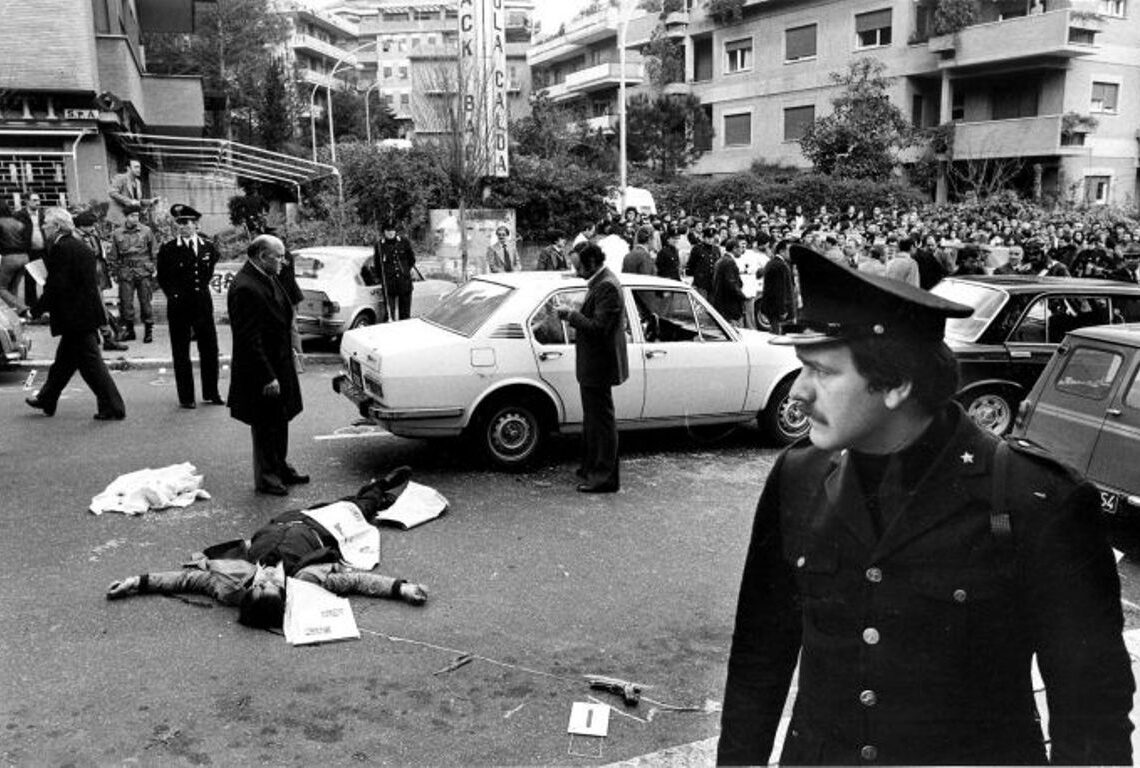

Moro was kidnapped in Via Fani, Rome, on the same day he was heading to the Italian Parliament to debate the first coalition government that would include the Italian Communist Party.

After 55 dramatic days of botched tracking and failed negotiations, the body of Moro was found in a red Renault in the very center of Rome.

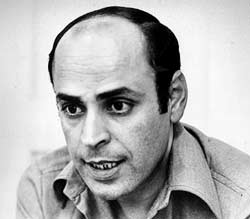

The Red Brigades had taken an increasingly violent turn after Mario Moretti, the most ambiguous of its founders, took the helm of the organization, following the arrests of the previous leadership in 1974.

The official line is that the Red Brigades had always operated independently of any assistance or government protection.

Subsequent inquiries have largely invalidated the standard storyline, showing extensive external protection and manipulation of the “red terror” group, on the side of intelligence agencies and government apparatus.

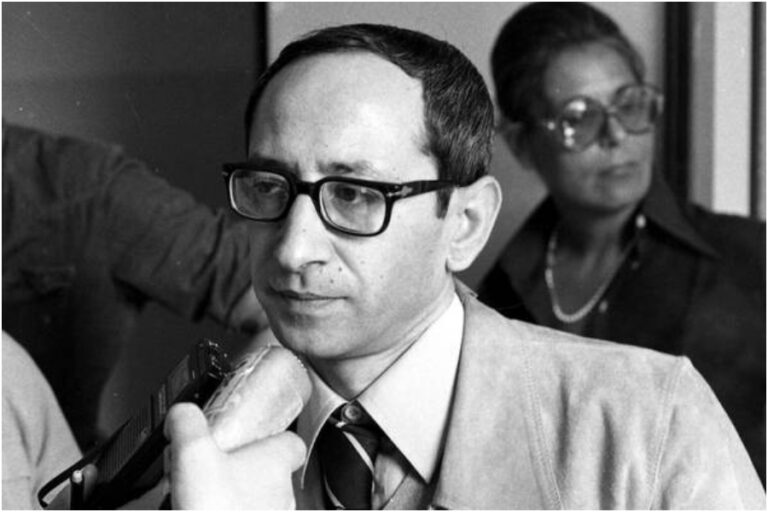

An early critic of the official account, and most competent expert of the Red Brigades, is Senator Sergio Flamigni.

Flamigni, a member of the early parliamentary commission on the Moro affair, established in 1979, has investigated the case for more than 40 years and published extensively on the topic.

The Senator is also responsible for the organization of an archive and documentation center on the Moro case.

Flamigni was ultimately able to reconstruct the real profile of Mario Moretti, exposing sensitive and substantial information that completely contradicts the accepted narrative.[11]

Digging in his early years, Flamigni was first able to find out that, far from being the radical Marxist he was eventually portrayed as, Moretti had a neo-fascist political background.

This information is disturbing enough on its own. Ever more so, it dovetails flawlessly with other major criminal investigations in Italy, which exposed a complex hub of connections and complicity between intelligence services, domestic and NATO’s, and right-wing terrorist groups.[12]

Flamigni was also one of the early observers to note that the Red Brigades did not have the operational capability to pull off such an extremely complex operation as the kidnapping of a top-level politician like Aldo Moro, who was protected by a tight security detail (to abduct Moro, the “Red Brigades” had to attack and kill the entire Moro escort, consisting of five professional law enforcers).

It is essential to stress that the differences between the Moretti and the Carlos case, certainly significant, are to the disadvantage of the official version in the Moretti affair (with the exception of the time interval of the reported track, evidently longer in the case of Carlos).

First, Moretti, just as much as the Red Brigades in general, could not benefit from military training even remotely comparable to that of Carlos.

It is a matter of common knowledge that most Red Brigades members, including Moretti, actually maintained quite a bourgeois lifestyle.

More importantly, even though the Red Brigades enjoyed extensive international connections, Moretti could not claim any “safe haven” country granting him political and security protection.

During the most sensitive years, the Italian terrorist operated essentially in his home country, well “under the nose” of domestic law enforcement and intelligence services.

It is a matter of record that Italian intelligence and security services had successfully infiltrated the Red Brigades.

One of the most powerful Italian intelligence officers during the Cold War, Federico Umberto d’Amato, known as “the Italian Hoover,” also admitted as much in a 1992 BBC documentary on Operation Gladio.

It was as a result of such infiltration that the leadership of the group, prior to the Moretti era, could be arrested in its entirety in September 1974.

Yet, as Flamigni notes sarcastically, Moretti happened to be way luckier. He continued to evade capture for more than six years, and was ultimately arrested in Milan only on April 4, 1981, after more than nine years of clandestine life, and three years after having supposedly orchestrated the kidnapping, detention and assassination of Aldo Moro.

It has also been known for a long time that the government Crisis Committee, established to manage the Moro kidnapping in 1978, was largely made up of members of the notorious Masonic Lodge P2, headed by U.S. asset Licio Gelli, including the heads of Italian military and civil intelligence, General Giuseppe Santovito and General Giulio Grassini, respectively.[13]

The plan of Moro to involve the Italian communists in the government had always been resisted by the U.S. and NATO, especially by Henry Kissinger.

Considering the neo-fascist agenda and affiliation of the P2, it is at the very least incongruous that members of the Lodge were in charge of handling the Moro crisis.

It is precisely because of the extremely problematic flaws of the government-supported narrative that the Moro affair continues to engender controversy.

After the first parliamentary commission of inquiry in 1979, multiple criminal trials focused on the case throughout the 1980s.

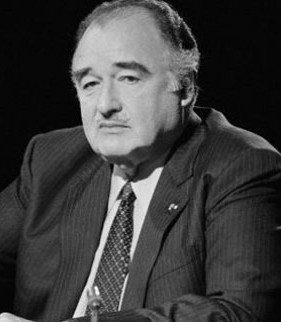

And new, critical investigative developments occurred in the 2000s. Among these is the revelation of the extremely ambiguous role played by Steve Pieczenik, a Cuban-born, Harvard-trained psychiatrist and international crisis manager at the U.S. State Department.

In 2008, it was revealed that Pieczenik, sent by President Carter to assist the Moro Crisis Committee in 1978, had been crucially instrumental to the ultimate fate of Moro.

Italian investigators strongly suspected that the real mission of Pieczenik was to prevent Moro from ever getting out alive.

The New Moro Commission

The persistent discrepancies and new findings prompted the creation of a new Parliamentary Commission, during the 17th legislature, which completed its work in December 2017.

The last “Moro Commission” produced several reports documenting its extensive findings. The Commission reports endorsed the implausibility of the official narrative, exposing evident protection of the Red Brigades on the side of military intelligence and law enforcement.

Top insiders testified to the Commission, calling into question, when not directly contradicting, the standard account.

The most damning disclosures, largely under-reported, possibly came from investigative magistrate Pietro Calogero.

In the late 1970s, Calogero, who had already developed considerable experience in high-profile cases of terrorism, conducted a very sensitive investigation tying the Red Brigades to another well-known radical left group, Autonomia Operaia.

Calogero testified to the last Moro Commission on November 11, 2015. However, large chunks of his statements, deemed extremely sensitive, originally were classified.

The author extensively interviewed prosecutor Calogero, who confirmed and elaborated on the critical information shared in his testimony.

Calogero told the parliamentary committee that, in 1979, he was contacted by then-Colonel (and future General) Pasquale Notarnicola, head of the counter-terrorism division of Italian military intelligence (SISMI), for a highly confidential meeting.

Notarnicola, claiming to represent the “loyalist” group of SISMI, was acting unbeknownst to his superiors.

He revealed to Calogero that SISMI had learned, as early as 1974, that the Red Brigades and Autonomia Operaia were indeed in close contact, and the leaders of the two met frequently.

Crucially, he told Calogero, showing him classified military intelligence to that effect, that the Red Brigades had been identified and monitored for exactly as long, and extensive files existed on them.

Considering that the most violent crimes were perpetrated by the Red Brigades under the Moretti leadership, i.e., after 1974, the implications of this hypersensitive disclosure was quickly understood by Calogero.

What the General was implying, and that Calogero bitterly regretted throughout his life, and in his own testimony to the Parliament, was that the Red Brigades could have been easily exposed and stopped, years in advance.[14]

A mystery inside the Moretti mystery: the language school Hyperion.

Calogero also confirmed and expanded on the details of a previously known, yet equally sensitive investigation, concerning the much discussed episode of the “language school” Hyperion, an organization tied to Moretti and Western intelligence.[15]

Moretti had maintained all along close ties to a group of original members of the Red Brigades, who then assumedly departed from the organization for ideological divergence, and was known as the “Superclan,” meaning “super-clandestine,” led by Corrado Simioni.

The ”Superclan” founded a mysterious school of languages, denominated “Hyperion,” that appeared to serve quite a different purpose. The headquarters of the Hyperion was in Paris, to where Moretti traveled frequently.

An investigation promoted by Calogero, and ultimately run by French domestic intelligence (Renseignements Généraux) and Police Commissioner Luigi de Sena, led to the discovery of a connection between the Parisian location of the Hyperion and a facility in Rouen, Normandy.

French investigators found out that the Rouen structure, a villa, was protected by highly sophisticated technical systems, including triple sensor-rings, set up to alert against intrusion.

The officers of the Renseignements Généraux, Calogero reported, explicitly told de Sena that foreign intelligence used that type of structure, and that the system of the Rouen villa, in particular, was used by the Americans.

The continuous surveillance of the Hyperion led to the discovery of two more centers, in Brussels and London.

However, at that point, leaks to the press and other acts of sabotage, most likely orchestrated by intelligence services, forced Calogero and de Sena to abruptly terminate the investigation.[16]

The mystery of the Hyperion has yet to be solved.

As may be seen, the disclosures from Calogero do not take place in a vacuum. They fit a consistent pattern of revelations.

Multiple parliamentary and criminal investigations, taking place in several European countries, have exposed the complicity of Atlantic intelligence in some of the most notorious acts of terrorism in Europe during the Cold War.[17]

The leadership of the Italian SISMI in the 1978-1981 period, particularly General Giuseppe Santovito, General Pietro Musumeci and Colonel Giuseppe Belmonte, was involved in other highly controversial episodes of terrorism.

In particular, they were investigated and (in the case of Musumeci and Belmonte) convicted definitively for obstructing the investigation into the most serious terrorist attack in Italian history, the bombing of the Bologna railway station in August 1980.

They also turned out to have extensive connections with the U.S. political and intelligence establishments, particularly through their affiliation with Masonic Lodge P2, led by Gelli, who was also convicted for cover-up activities against the Bologna criminal inquiry.[18]

In 2018, General Notarnicola also testified in new criminal investigations, concerning the Bologna station bombing of August 2, 1980.

He confirmed, adding sensitive disclosures, that the leadership of military intelligence, aided by U.S. agents, had intimate knowledge of the Bologna case and had, from the beginning, consistently sabotaged the judicial investigation into it.

At this writing, beside the Bologna case, most critical trials are taking place in Italy, especially in the jurisdiction of Brescia, where NATO is explicitly charged, for the first time, with backing right-wing terrorism in Italy throughout the Cold War.

This story is still to be written.

-

Quoted in Roger Faligot and Pascal Krop, DST, Police Secrete, Flammarion, 1999, p. 306 (not available in English). ↑

-

The following works deserve to be cited: Jeffrey M. Bale, The Darkest Sides of Politics, I: Postwar Fascism, Covert Operations, and Terrorism (New York: Routledge, 2017); Daniele Ganser, NATO’s Secret Armies: Operation GLADIO and Terrorism in Western Europe (New York: Routledge, 2005) (with an important introduction from the late historian of the National Security Archive, John Prados); Mark Curtis, Secret Affairs: Britain’s Collusion with Radical Islam (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2018) (updated edition); Phillip Willan, Puppetmasters: The Political Use of Terrorism in Italy (Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 2002); Ola Tunander, The Use of Terrorism to Construct World Order, Paper presented at the Fifth Pan-European International Relations Conference (Panel 28 Geopolitics), Netherlands Congress Centre, The Hague, September 9-11, 2004. ↑

-

For an authoritative account of U.S. involvement, see Billy Waugh and Tim Keown, Hunting the Jackal: A Special Forces and CIA Soldier’s Fifty Years on the Frontlines of the War Against Terrorism (New York: William Morrow, 2005). Waugh was the U.S. agent intimately involved in the preparatory phase of the ultimately successful operation in Sudan. As to English-language sources, see also John Follain, Jackal. The Complete Story of the Legendary Terrorist, Carlos the Jackal (Arcade Publishing, 2011) (2nd edition). ↑

-

This author, obviously, does not question the good faith of intelligence, law enforcement officers and other operatives who were genuinely involved in the pursuit of Carlos. However, this type of operation, due to its extreme sensitivity, is highly compartmentalized. The record shows that officers who are not deemed dependable or friendly to the objective of such operations are marginalized, outmaneuvered or simply kept in the dark. ↑

-

Les Tueurs de la République, Assassinats et opérations spéciales des services secrets, Editions Fayarde, 2015 (not available in English). Canal +, a major French chain, has just released a three-part documentary, based on Nouzille’s book. Interestingly, Les Tueurs de la République is one of the few books from this author that is not listed in the Library of Congress Catalogue. ↑

-

Roger Faligot and Pascal Krop, La Piscine: les services secrets français 1944-1984, Editions du Seuil, 1985, p. 328. ↑

-

Nouzille, Les Tueurs de la République, pp. 127-137. ↑

-

Waugh and Keown, in Hunting the Jackal, p. 285, mention briefly the global track led by Philippe Rondot. However, they seem to be unaware and make no mention of other sensitive disclosures from the French investigations, particularly the remarks of de Lignières (whose name does not appear at all). Follain’s book was originally published in 1998, before the first known revelation of de Lignieres’ claims. However, even in the 2nd edition, released in 2011, there is no mention of this disclosure, and the author is quite dismissive of the whole San Cristobal episode. ↑

-

That, of course, is not the case. The Moumié affair was exposed and did prompt a serious political crisis. ↑

-

Of the material cited at note 1, see especially Ganser, NATO’s Secret Armies, and Curtis, Secret Affairs. ↑

-

Sergio Flamigni, La sfinge delle Brigate Rosse. Delitti, segreti e bugie del capo terrorista Mario Moretti (Kaos, 2004) (not available in English). ↑

-

See, in particular, Bale, The Darkest Sides of Politics, and Willan, Puppetmasters, ↑

-

Willan, Puppetmasters, ch. 11, provides an effective overview of the Moro kidnapping. ↑

-

Testimony of Pietro Calogero to the Italian Parliamentary Commission of Investigation into the Aldo Moro case, XVII Legislature, November 11, 2015, pp. 11-13; telephone interview with the author, May 12, 2023. Calogero had revealed part of this information in the interview book Terrore Rosso, published in 2010. ↑

-

The story of the Hyperion is discussed quite extensively in Willan, Puppetmasters,, ch. 10, but it does not include the details on the Normandy investigation shared by Calogero. ↑

-

Testimony of Calogero to the Moro Commission, pp.7-9. De Sena was dispatched to investigate the London bureau of the Hyperion, in a mission that was known only to a restricted group of British officials. In returning to his London room one night, he found it completely ransacked, although nothing had been stolen. In the May 12, 2023, interview, Calogero recalled and confirmed this episode very precisely. He also insisted that it was the reference to the Rouen villa as a possible U.S. intelligence facility, which prompted the expansion of the investigation to other Western European countries. ↑

-

See in particular, Ganser, NATO’s Secret Armies, for the role played by stay-behind structures; also Willan, Puppetmasters, for the Italian case. ↑

-

The most up-to-date account of the long investigation into the Bologna bombing is in the recent Criminal Judgment against Paolo Bellini, Court of Bologna, April 6, 2022 (the grounds were filed on April 5, 2023). ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Denis Voltaire is a researcher from France who has studied and worked in Washington, D.C.

If anyone wants to dig deeper, here’s more:

Articles

“Moretti infiltrato? Una leggenda nera fabbricata a tavolino da Sergio Flamigni”

“Armando Spataro: <>”

“Pietro Calogero, Carlo Fumian, Michele Sartori, Terrore rosso. Dall’autonomia al partito armato”

“Aldo Moro, 42 anni dopo fa effetto leggere di una querela. E la verità è ancora lontana”

Books:

La pazzia di Aldo Moro Formato Kindle – Marco Clementi (book)

Storia delle Brigate Rosse – Marco Clementi (book)

Brigate rosse. Dalle fabbriche alla «campagna di primavera» (book)

La strage di Bologna. Bellini, i Nar, i mandanti e un perdono tradito – Paolo Morando (book)

Brigate Rosse. Storia del partito armato dalle origini all’omicidio Biagi (1970-2002) (book)

Armando Spataro: Quelle carte delle Br ci aiutano a ricordare gli errori di un’epoca

I wish you would have put much effort and diligence in your research. If you did, you would have found out that all your sources are simply fake news.

Sergio Flamigni’s “theories” (as much as Enzo Raisi’s, or Alessandro Marini’s or Gero Grassi’s and many others’) have been debunked since long time.

There are so many available sources that come from italian historians and reliable journalists. You should give it a try, but, well, I suppose the so called “investigative left” loves to borrow fascist conspiracy theories just to believe that everything is infiltrated or corrupted by the “highest powers”.

The Red Brigades were real. Sorry to disappoint you but no Operation SOLO for you..

I agree and was most disappointed with this article for its regurgitation of already debunked propaganda.

…

The writers for Covert Action Magazine who do not show a photo of themselves and do not give their e-mail address seem to have very similar writing styles. So I am wondering if this is one person using different names. .