Between 1975 and 1991, Cuba embarked on a remarkable internationalist mission known as Operación Carlota. This mission was undertaken to defend Angola’s newly found independence from an invasion by apartheid-era South Africa, and it played a pivotal role in the broader African anti-colonial and national liberation struggles.

Over 400,000 Cubans participated in various capacities, including as soldiers, doctors, teachers, engineers and construction workers, with more than 2,000 making the ultimate sacrifice.

However, the extensive and decisive role of Havana in the fight against apartheid South Africa has often been marginalized in Western narratives, with some treating it as if it never happened.

Yet, the significance of Cuba’s involvement cannot be erased. Indeed, Havana’s commitment to defending Angola’s independence and the right to self-determination of southern African peoples was unwavering.

Africa’s Children Return!

Named after a Cuban slave revolt leader from 1843, Operación Carlota was initiated on November 5, 1975, in response to Angola’s urgent plea for assistance. The country had just achieved independence after a grueling anti-colonial struggle but faced a dire threat from South Africa, which aimed to topple Angola’s Black government.

Not only did Operación Carlota halt the South African advance toward Luanda, the capital of Angola, but it also pushed them out of the country entirely. This defeat marked a major turning point in the African anti-colonial struggle.

The World, a South African newspaper at the time, highlighted its significance by stating that “Black Africa is riding the crest of a wave generated by the Cuban success in Angola. Black Africa is tasting the heady wine of the possibility of realizing the dream of “total liberation.”

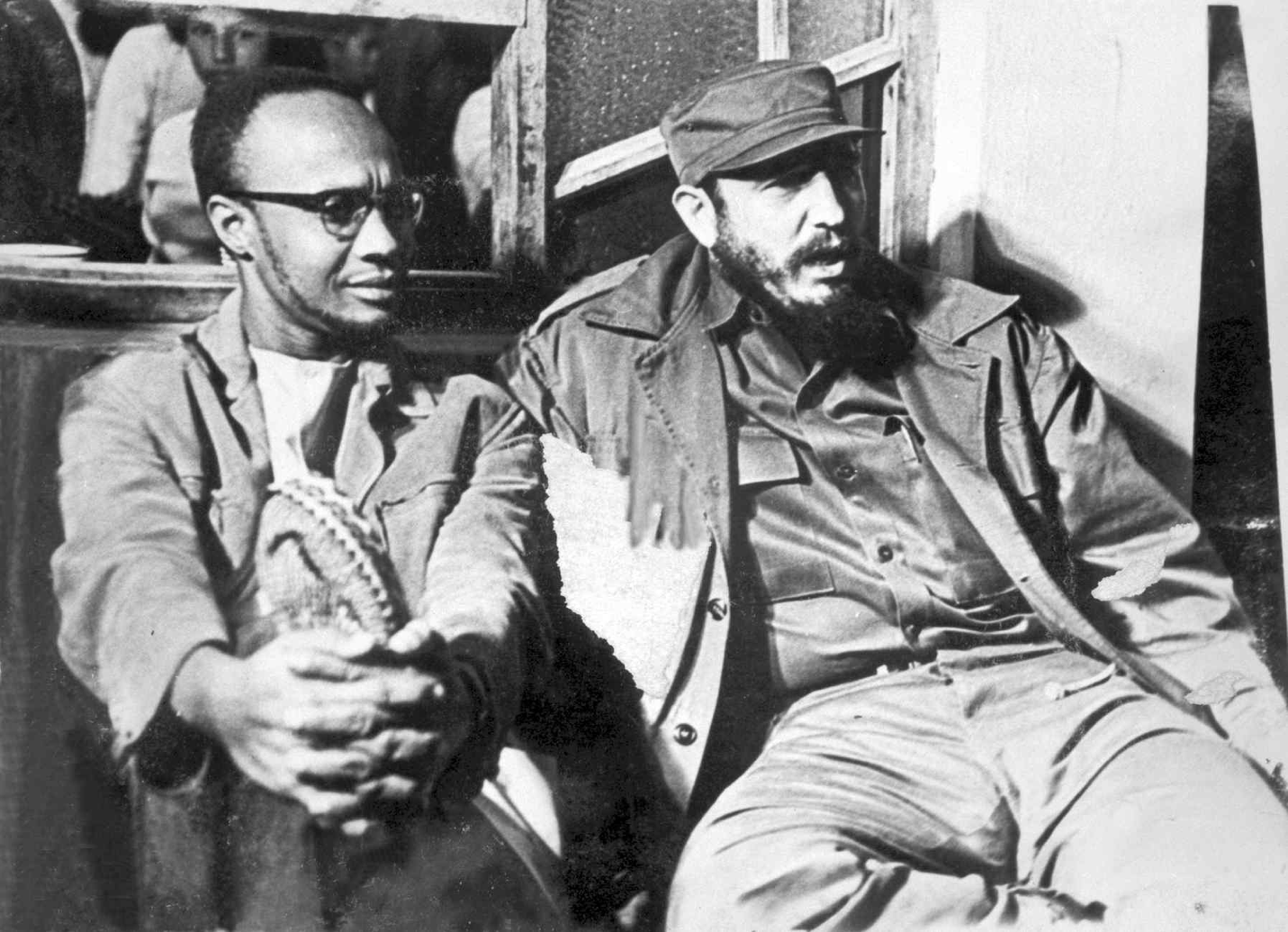

Cuba’s solidarity with Angola went beyond mere assistance between nations: It represented a part of the African diaspora rising to the defense of Africa. Since the Cuban Revolution of 1959, Cuba had been actively involved in supporting Africa’s liberation struggles.

This support was deeply appreciated by African leaders. Amilcar Cabral (celebrated leader of the anti-colonial and national liberation struggle in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde) declared: “I don’t believe in life after death, but if there is, we can be sure that the souls of our forefathers who were taken away to America to be slaves are rejoicing today to see their children reunited and working together to help us be independent and free.”

The Cuban Revolution’s involvement with Angola began in the 1960s when relations were established with the Movement for the Popular Liberation of Angola (MPLA). The MPLA was the principal organization in the struggle to liberate Angola from Portuguese colonialism. In 1975, the Portuguese withdrew from Angola.

However, to prevent the MPLA from coming to power, the U.S. government had already been funding various groups, in particular, the Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) led by the notorious Jonas Savimbi. In October 1975, South Africa, with the complicity of Washington, invaded Angola. On November 5, 1975, the Cuban revolutionary leadership met to discuss the situation in Angola and the Angolan government’s request for military assistance to repel the South African invasion force. The decision to deploy combat troops thwarted apartheid South Africa’s goal of turning Angola into its client state.

The Cuban leadership justified their military intervention by framing it as both the defense of an independent nation against foreign invasion and the fulfilment of a historical debt owed by Cuba to Africa. Fidel Castro frequently invoked Cuba’s historical ties to Africa, emphasizing this connection. On the 15th anniversary of the Cuban victory at Playa Girón (Bay of Pigs), he proclaimed that Cubans constituted a “Latin-African people.”

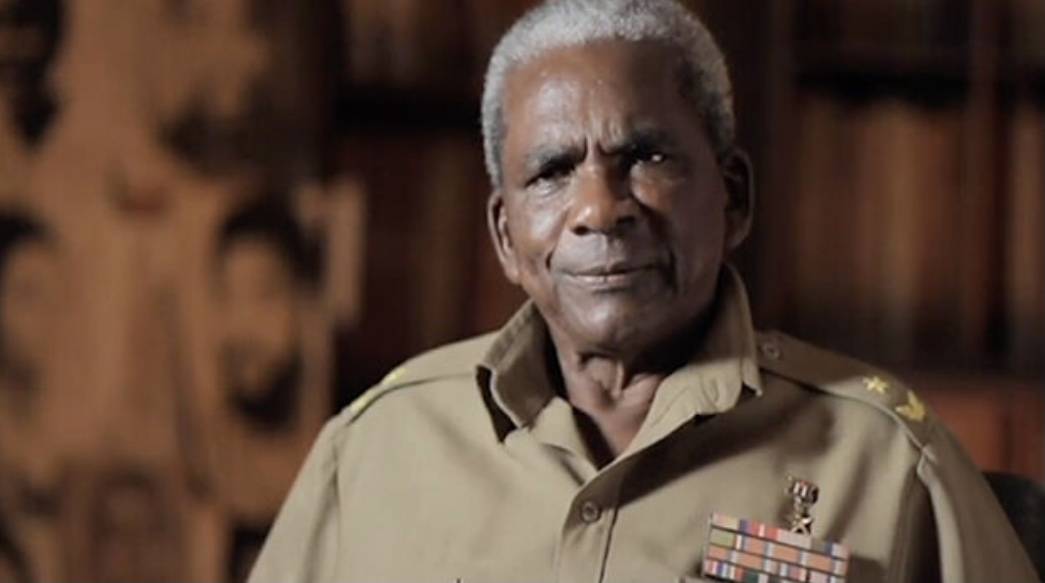

Jorge Risquet, Havana’s chief diplomat in Africa from the 1970s to the 1990s, was unequivocal in explaining Cuba’s military involvement in terms of its responsibilities to Africa. This association struck a deep chord with Black Cubans, allowing them to symbolically reconnect with their African heritage. For many Black Cubans, participating in the fight in Angola felt like defending Cuba once more, only this time on African soil. They were acutely aware that Africa held a special significance as their ancestral homeland.

Reverend Abbuno González underscored this profound connection, stating: “My grandfather came from Angola. So, it is my duty to go and help Angola. I owe it to my ancestors.”

General Rafael Moracén echoed this sentiment and invoked the words of Amilcar Cabral, noting, “When we arrived in Angola, I heard an Angolan say that our grandparents, whose children were taken away from Africa to be slaves, would be happy to see their grandchildren return to Africa to help free it. I will always remember those words.”

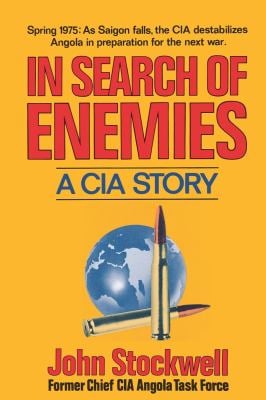

Cuban involvement in Southern Africa has been repeatedly dismissed as surrogate activity for the Soviet Union. This misleading misconception—in reality, an insidious myth—has been emphatically refuted.

John Stockwell, who served as the director of CIA operations in Angola during and immediately following the 1975 South African invasion, explicitly refuted this notion in his memoir, In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story. He affirmed, “We learned that Cuba had not been directed into action by the Soviet Union. Quite the opposite, Cuban leaders felt compelled to intervene due to their own ideological convictions.”

In the widely acclaimed book Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-76 Professor Piero Gleijeses demonstrated that the Cuban government, as it had consistently asserted, made the decision to send combat troops to Angola only after the Angolan government had formally requested Cuba’s military assistance to repel the South African forces.

This disproves Washington’s claim that South African intervention in Angola occurred solely in response to the arrival of Cuban forces, and it further revealed that the Soviet Union played no role in Cuba’s decision and was not even informed prior to the deployment. Even The Economist magazine, which is not known for its favoritism toward Cuba, acknowledged in a 2002 article that the Cuban government acted on its “own initiative.” In short, Cuba operated independently and was not acting as a puppet of the USSR.

The idea that Cuba could exercise its own agency independently of the dominant global powers was not only deeply unsettling to Washington but also considered unimaginable.

To Henry Kissinger, a National Security Adviser who later became the U.S. Secretary of State, it was an anathema. In 1969, he had made a stark and unequivocal statement: “Nothing important can come from the South. History has never been produced in the South. The axis of history starts in Moscow, goes to Bonn, crosses over to Washington, and then goes to Tokyo. What happens in the South is of no importance.”

The fact that Cuba, an economically poor “Third World” nation with strong Latin-African ties, could take independent actions that influenced historical events incensed Kissinger.

In response to Cuba’s audacity in challenging the established imperial order, complete with its racially based global hierarchy, Kissinger initiated the development of extensive military plans by the Pentagon in 1975 and 1976. These plans were specifically designed to retaliate against the island for daring to defy the established order.

They encompassed a range of options, from a naval blockade to aerial bombardment to an outright invasion. Although these plans were ultimately not put into action, they were the subject of serious discussion and deliberation at the highest levels of the U.S. government. This highlights the very real risks that Cuba faced, and willingly accepted, during its internationalist defense of Angola.

It is important to emphasize that Washington was a steadfast bulwark of the apartheid regime, particularly during the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. Chester Crocker, who served as Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs from 1981 to 1989, encapsulated this stance in a discussion with New York Times‘ correspondent Joseph Lelyveld, asserting that “the whites are here to stay” and praising the South African armed forces’ general staff as “modernizing patriots.” He declared that it was not Washington’s primary “task to choose between black and white but to defend Western interests…economic, strategic, moral and political.”

Crocker went on to underscore the deep ideological affinity and connection between Washington and the apartheid regime, stating that “[h]istorically, South Africa is by its nature a part of the U.S.” South African Foreign Minister Roelof Botha reinforced this sentiment after his visit to Washington in May 1981, stating that there had never been a U.S. government more favorably disposed towards South Africa since World War II.

South Africa’s War of Terror

Pretoria concluded, especially after its 1975-76 defeat in Angola, that the survival of the racist South African state hinged upon its ability to assert dominance over all of Southern Africa. This conviction was underscored by the 1977 White Paper on Defence, crafted under the leadership of Prime Minister P.W. Botha, which asserted that the fundamental issue at stake was “the right of self-determination of the white nation.” To secure this, a comprehensive approach was deemed necessary, a “total strategy” that would extend across all facets of social and political life.

This “Total Strategy” was defined as “coordinated and interdependent action across all domains—military, psychological, economic, political, sociological, technological, diplomatic, ideological, cultural, and more.”

Defence Minister General Magnus Malan declared that South Africa was “involved in a total war.” Consequently, Pretoria militarized the South Africa state, fashioning it into the sword to defend the racist system and wage a regional war of terror.

As a result, the struggle against apartheid unfolded both within and beyond the borders of South Africa. From 1975 to 1988, the apartheid regime sought to solidify and expand its regional dominance through a brutal campaign of destabilization. The South African armed forces exacted a profound toll in both human and financial terms. These costs encompassed not only direct damage and loss of life but also the premature deaths and anticipated economic decline stemming from the destruction of infrastructure, agriculture and power networks.

Although quantifying the exact economic cost and damage is challenging, it was undoubtedly staggering. One study estimated that, by 1988, the total economic toll on the Frontline States exceeded $US 45 billion. For instance, Angola bore a cost of $US 22 billion, Mozambique $US 12 billion, Zambia $US 7 billion, and Zimbabwe $US 3 billion.

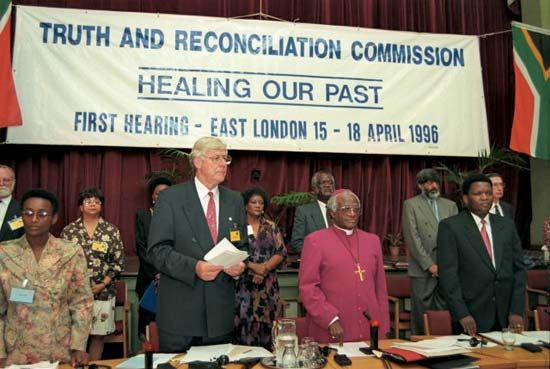

The human suffering during this period was staggering. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa emphasized this grim reality, stating, “the number of people killed inside the borders of the country in the course of the liberation struggle was considerably lower than those who died outside….[T]he majority of the victims of the South African government’s attempts to maintain itself in power were outside South Africa. Tens of thousands of people in the region died as a direct or indirect result of the South African government’s aggressive intent towards its neighbours. The lives and livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of others were disrupted by the systematic targeting of infrastructure in some of the poorest nations in Africa.”

Between 1981 and 1988, an estimated 1.5 million people, including 825,000 children, tragically lost their lives, either directly or indirectly. These losses were primarily the result of insurgencies sponsored by Pretoria, specifically UNITA in Angola and Renamo in Mozambique, as well as direct military interventions by the South African armed forces.

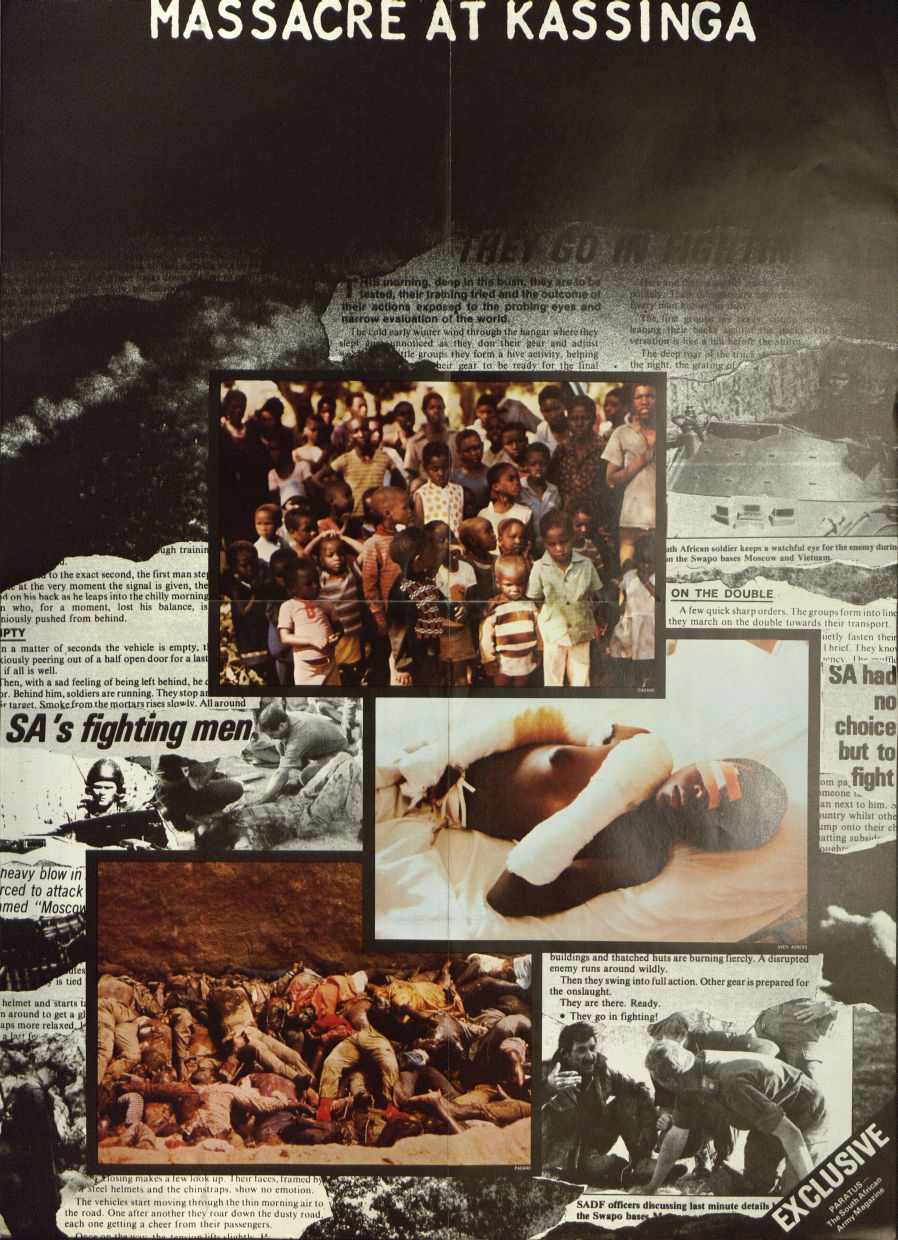

South Africa launched numerous bombing raids, armed incursions, and carried out assassinations in neighboring countries. One particularly notorious incident was the massacre on May 4, 1978, at a camp for Namibian refugees situated in Kassinga in southwestern Angola. In this horrifying attack, South African air and paratrooper forces killed hundreds of individuals and took hundreds more as prisoners.

Cuito Cuanavale

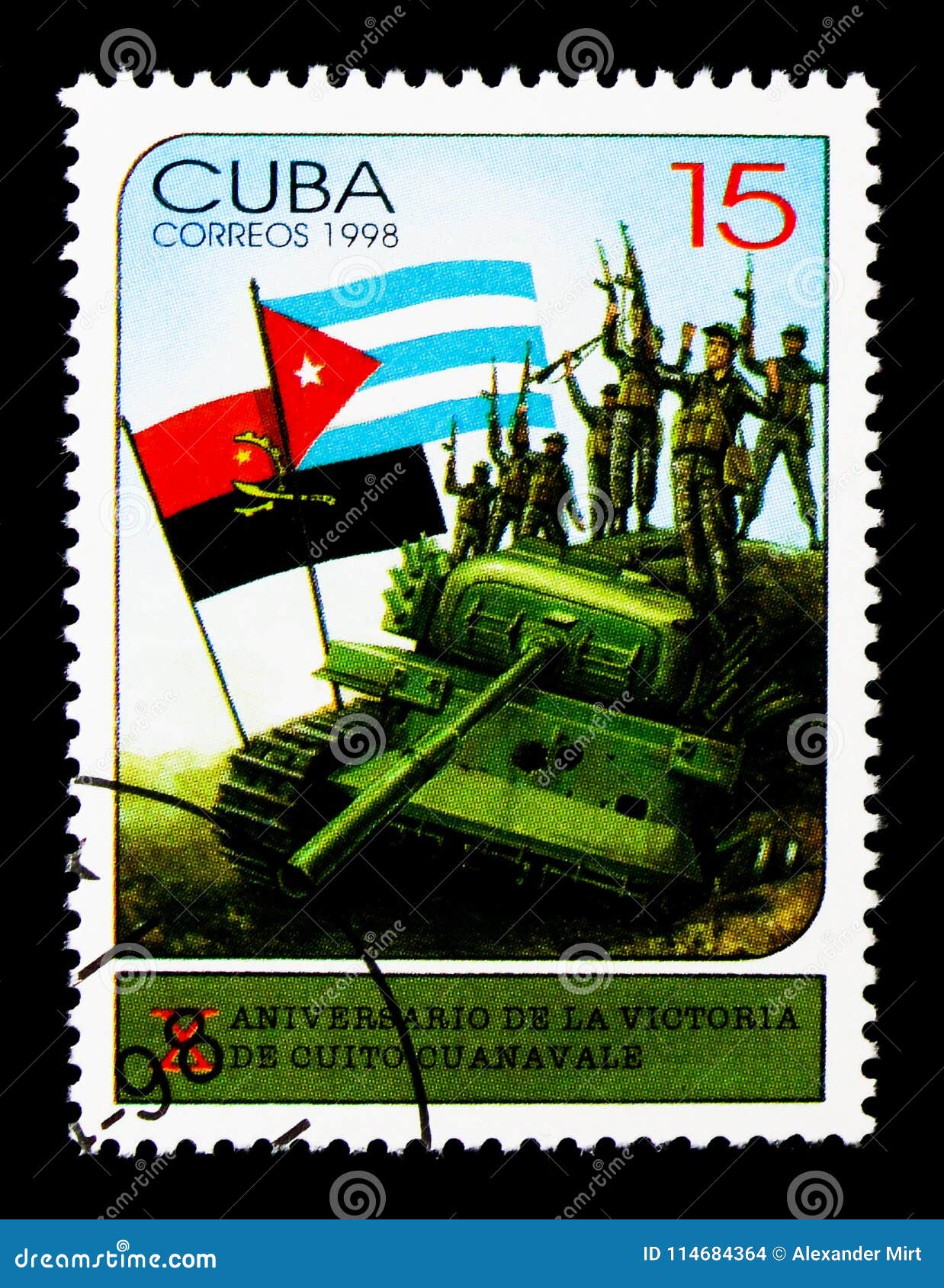

In the years 1987-1988, a series of pivotal battles unfolded in the vicinity of the southeastern Angolan town of Cuito Cuanavale. At the time, these battles stood as the largest military confrontations in Africa since the North African conflicts of the Second World War.

On one side of this intense confrontation were the combined armed forces of Cuba, Angola and the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO). On the opposing side, they faced the South African Defense Forces, military units of the Union for the Total National Independence of Angola (UNITA)—which acted as a proxy organization for South Africa, and the South African Territorial Forces of Namibia (which was still under illegal occupation by Pretoria at that time).

The significance of Cuito Cuanavale cannot be overstated in the struggle against apartheid.

From November 1987 to March 1988, the South African armed forces made multiple unsuccessful attempts to capture Cuito Cuanavale. Within Southern Africa, these battles have achieved legendary status. They are often characterized as the turning point against apartheid—a decisive defeat for the South African armed forces that shifted the regional power balance and foreshadowed the eventual end of racist rule in South Africa.

Cuito Cuanavale effectively thwarted Pretoria’s ambitions of establishing regional dominance, a strategy that was crucial to upholding and preserving apartheid. It directly led to Namibia’s independence and accelerated the dismantling of apartheid. This battle is frequently likened to the African equivalent of the Battle of Stalingrad during World War II. Cuba’s role in this pivotal moment was critical, as it provided essential reinforcements, resources and strategic planning.

In July 1987, the Angolan armed forces, known as FAPLA, initiated an offensive against UNITA, which was acting as a surrogate for the apartheid state. The Cubans expressed strong reservations about this military operation because they believed it could create an opportunity for a South African invasion, a concern that unfortunately materialized. South African forces launched an invasion, successfully halting and repelling the advancing Angolan troops. The Angolan forces, after enduring significant human and material losses, were forced into a rapid retreat toward the strategically important town and military stronghold of Cuito Cuanavale.

As the conflict increasingly focused on Cuito Cuanavale, the Angolan armed forces found themselves in an exceedingly precarious situation, with their most elite units facing the imminent threat of annihilation. Angola’s very existence was on the line. If Cuito Cuanavale were to fall to South Africa, the entire country would be vulnerable to the invaders. Angolan General Antonio dos Santos stressed the overarching importance of defending the town, emphasizing that, if the South Africans prevailed at Cuito Cuanavale, “the road would be open to the north of Angola.”

Determined to transform their initial military success into a decisive blow against an independent Angola, Pretoria committed its finest troops and most advanced military equipment to the capture of Cuito Cuanavale. As the situation for the besieged Angolan troops grew increasingly dire, the Angolan government sought assistance from Havana. On November 15, 1987, Cuba made the decision to reinforce its forces, dispatching fresh detachments, arms and equipment, including tanks, artillery, anti-aircraft weapons and aircraft. Ultimately, the Cuban troop presence would exceed 50,000 personnel. It is essential to emphasize that, for a relatively small country like Cuba, deploying 50,000 troops would be equivalent to the United States deploying more than a million soldiers or Canada deploying more than one hundred thousand.

The level of commitment from Cuba was nothing short of monumental. Fidel Castro explicitly stated that the Cuban Revolution had “put its own existence at stake, it risked a huge battle against one of the strongest powers located in the Third World, against one of the richest powers, with significant industrial and technological development, armed to the teeth, at such a great distance from our small country and with our own resources, our own arms. We even ran the risk of weakening our defenses, and we did so. We used our ships and ours alone, and we used our equipment to change the relationship of forces, which made success possible in that battle. We put everything at stake in that action…”

For the Cuban government, preventing the fall of Cuito Cuanavale was a matter of utmost importance. A South African victory would have entailed not only the capture of the town and the decimation of Angola’s most formidable military units but, in all likelihood, the demise of Angola as an independent nation.

The Cuban revolutionary leadership made a significant decision to extend their efforts beyond the defense of Cuito Cuanavale. They chose to deploy the necessary forces and execute a plan aimed at conclusively ending South African aggression against Angola while delivering a decisive blow to the racist regime.

The successful defense of Cuito Cuanavale served as a prelude to a comprehensive and far-reaching strategy that would reshape the regional power dynamics.

South Africa’s attempts to capture Cuito Cuanavale encountered formidable resistance from the Cubans and Angolans. While the South African forces were engrossed in their efforts at Cuito Cuanavale, the Cubans executed a brilliant strategic maneuver. With the South Africans stymied at Cuito Cuanavale, to the west, along the Angolan/Namibian border, Havana deployed a substantial force of 40,000 Cuban troops, backed by 30,000 Angolan and 3,000 SWAPO troops. Pretoria’s intense focus on seizing Cuito Cuanavale had inadvertently left them vulnerable to a significant military counterattack.

The Cubans, in collaboration with Angolan and SWAPO forces, commenced an advance toward Namibia. This forward movement laid bare the insecurity and vulnerability of the South African troops stationed in northern Namibia. The situation was so precarious that a high-ranking South African officer admitted, “Had the Cubans attacked [Namibia] they would have over-run the place. We could not have stopped them.”

This vulnerability was further exacerbated by South African setbacks in late June 1988 at Calueque and Tchipia, where the South African forces suffered substantial defeats, described by a South African newspaper as “a crushing humiliation.” Additionally, Cuba gained control of the skies, achieving air supremacy. Faced with the formidable new force assembled in southern Angola and the loss of aerial dominance, the South African forces withdrew from Angola.

Paradoxically, while Cuito Cuanavale remains largely overlooked and ignored in the prevailing Western narrative of apartheid’s end, at the time of the military engagements, it received extensive coverage in Western newspapers.

Prominent stories appeared in what are often referred to as the “newspapers of record,” including The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The London Times, The Financial Times, and The Washington Post. These articles portrayed the battle as pivotal in shaping the future of the region, characterizing it as a major setback for South Africa that had a profound and transformative impact on the regional power dynamics.

The defeat suffered on the battlefield compelled South Africa to come to the negotiating table, ultimately leading to the independence of Namibia. Furthermore, it had a profound impact on the apartheid regime, accelerating its demise by exacerbating the existing social, political and economic contradictions within the militarized apartheid state. This transformative event fundamentally altered the regional balance of power.

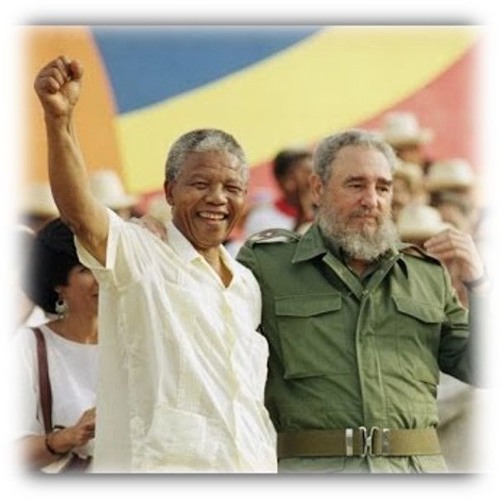

Victoria Brittain, a respected scholar on Africa, noted that Cuito Cuanavale became “a symbol across the continent, signaling that apartheid and its armed forces were no longer invincible.” In a significant July 1991 address delivered in Havana, Nelson Mandela underscored the pivotal role played by Cuito Cuanavale and Cuba in the struggle against the apartheid regime:

“The Cuban internationalists have made a contribution to African independence, freedom, and justice unparalleled for its principled and selfless character…It is unparalleled in African history to have another people rise to the defense of one of us. The defeat of the apartheid army was an inspiration to the struggling people in South Africa! Without the defeat of Cuito Cuanavale our organizations would not have been unbanned! The defeat of the racist army at Cuito Cuanavale has made it possible for me to be here today!”

Cuito Cuanavale was integral to apartheid’s death throes. Alongside pivotal events like the Sharpeville Massacre, the Rivonia Trial, and the Soweto Uprising, Cuito Cuanavale stands as one of the most significant chronological milestones in the struggle against apartheid.

Cuba’s involvement in Operación Carlota and the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale is a testament to the power of international solidarity and the willingness of a small nation to defy the world’s great powers in the name of justice and freedom. It is a story of sacrifice, determination and the transformative impact of collective action on the course of history.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Isaac Saney is a Cuba and Black Studies specialist at Dalhousie University, Canada, where he is an an Associate Professor and coordinator of the Black and African Diaspora Studies (BAFD) program, the first major in Black and African Diaspora Studies in Canada.

He is the author of Cuba: A Revolution In Motion (Zed Books 2004) and the recently published, Cuba, Africa, and Apartheid’s End: Africa’s Children Return! (Lexington Books 2023).

From 2008-2022, he served as co-chair and national spokesperson of the Canadian Network On Cuba, with which he now serves in an advisory capacity.

Isaac can be reached at isaac.saney@dal.ca.