Ah, Killers of the Flower Moon! An intriguing and brutal story that offers a window into early efforts of J. Edgar Hoover to kick over the murderous rocks and uncover the plot that plagued the Osage Indian Nation in the 1920s.

It is an enthralling tale of crime, greed and the pursuit of justice—with Martin Scorsese at the helm—and the reviews, by and large, reflect an enthusiasm for the film and the film’s content.

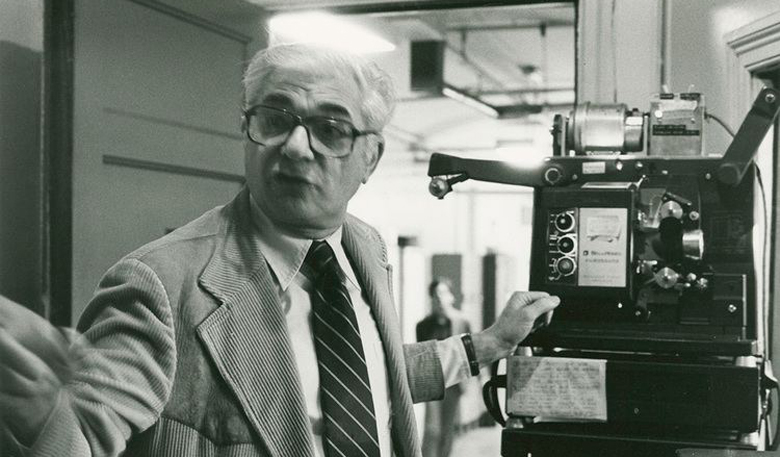

But this is not Scorsese’s first dalliance with fedora-wearing Feds; in fact, the FBI (together with other intelligence agencies) kept a file on both him and his NYU Film School mentor, Haig Manoogian.

I should know because, together with Steven Fischler and a few others—members of a radical anarchist group, Transcendental Students—we were responsible for precipitating these “visits” to NYU Film School by representatives of both the FBI and the NYPD’s much feared “Red Squad.”

While Martin Scorsese’s film version of Killers of the Flower Moon touches on the story of an FBI in its infancy—“Bureau of Investigation,” as it was originally called—Scorsese’s own interactions with the FBI illuminate a dark history of surveillance run wild, a history fraught with operational strategies designed to upset and derail any movement the police considered “too radical, like the movement to end the Vietnam War.

As part of a spy vs. spy chronicle (as New York Times reviewer Vincent Canby called it) and together with my Pacific Street Films partner, Steven Fischler, we were on the front lines while engaged in filming a documentary about the NYPD’s surveillance squad, known in the lingo as the Red Squad.

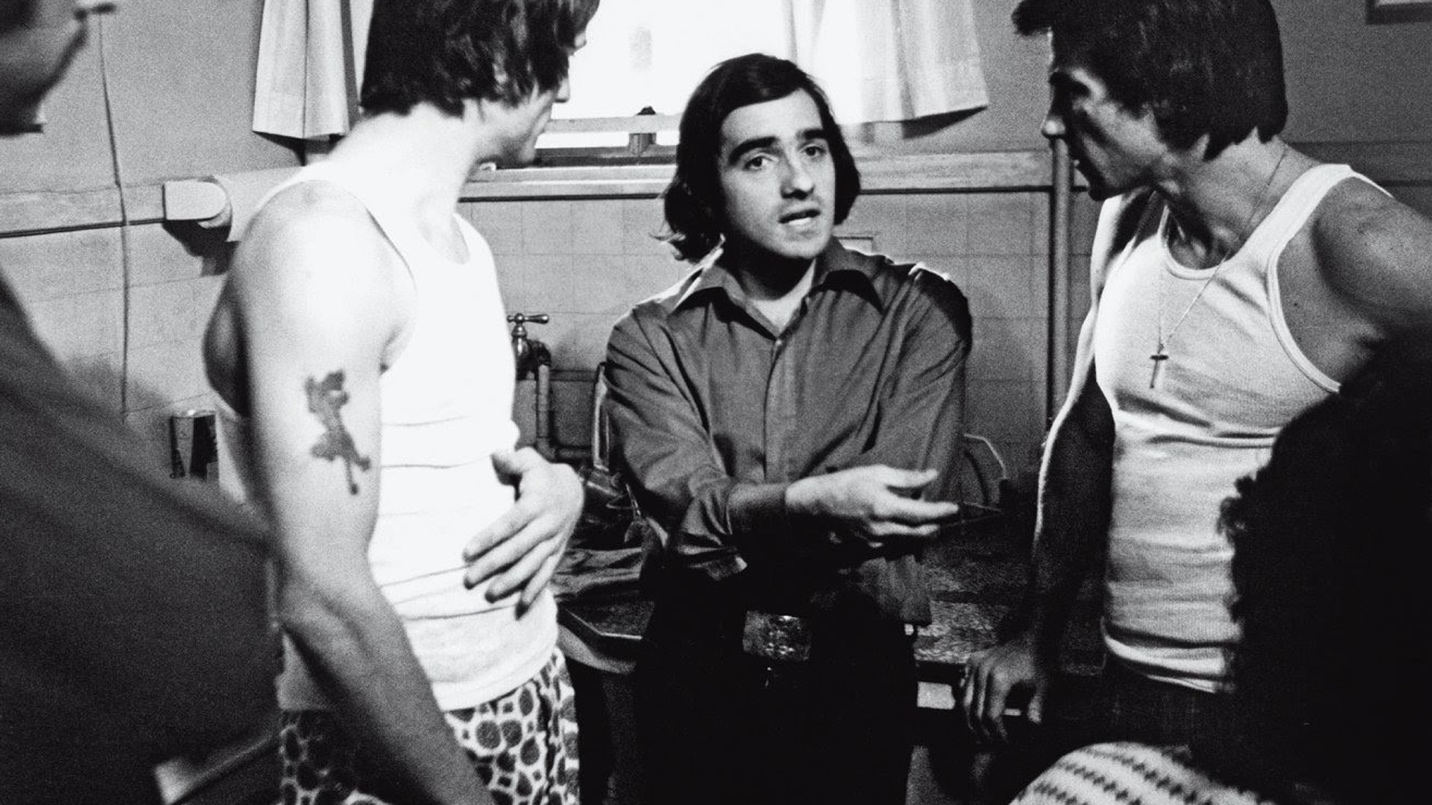

It was begun in 1970, while we were students in Scorsese’s Sight and Sound class (at the time, he was a teaching assistant). He was a fount of knowledge about all things cinema and knew that the then action was “on the street” and, to that end, he provided support and encouragement for us to document history in the making.

The streets at the time were awash with protests and, amid the faces of angry young men and women, there were characters who would show up with cameras trained on the crowd; sometimes they would approach and whisper “sweet nothings” in your ear, always addressing you by your first name. It was theater focused on reinforcing the notion that that you were being watched, 24/7.

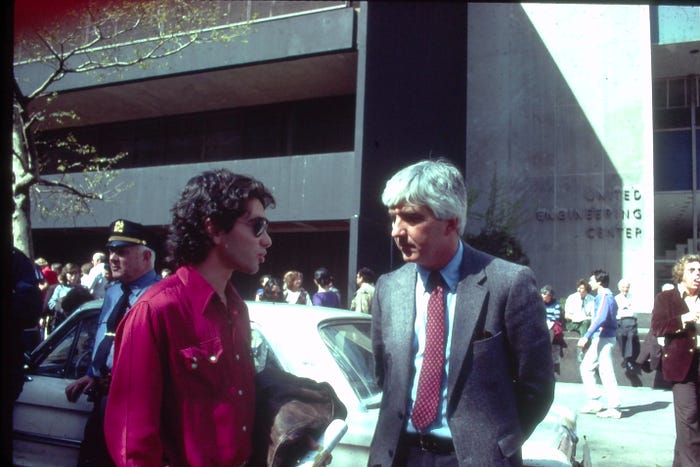

The most notorious of these characters was Detective John Finnegan, who would appear out of nowhere and begin a conversation in the midst of a noisy anti-Vietnam protest. The guy fit the part perfectly—well-dressed and good-looking—even appearing in an ad for suits.

The NYPD’s Red Squad would also manifest an undercover presence, infiltrating protest groups and, in some cases, fomenting violence which—as any self-respecting agent provocateur knows—results in saber-wielding Cossacks bearing down on protesting hordes.

But, as the opposition to the Vietnam War increased—and with hard-fisted attempts by the authorities to crack down—Scorsese was also inspired to take a more hands-on approach.

Together with like-minded cohorts, Scorsese helped organize something called the NYU Cinetracts collective. Inspired by a collective of French New Wave directors—including Jean-Luc Godard, Chris Marker and Alain Resnais—who banded together to produce short segments during the Paris uprisings of May/June 1968—in like fashion, the NYU group decided to take its cameras to American streets. The result was a documentary, Street Scenes, which premiered at the 1971 New York Film Festival.

We were card-carrying members of this group; albeit, we had embarked on our own camera-wielding career—under Scorsese’s umbrella—as members of the aforementioned Transcendental Students. The group’s mission statement highlighted efforts to liberate university space so that bored students could push out the paper and bring in the music, wine and pot.

These were fun times—and fun times making documentaries—and one, Inciting to Riot, was taken to the Festival dei Popoli by Scorsese. The other, I Am Curious Harold—made a year earlier—was a riff on the then popular I Am Curious (Yellow). It was a crude slapped-together cinéma vérité account of an NYU student strike (which included footage of a long-haired Scorsese arguing/debating with school administrators).

This was all Dziga Vertov (Man with a Movie Camera) in design and implementation.

Red Squad—which went on to find traction through many decades, including the present—was a project we discussed with Marty. His response was enthusiastic and, in turn, offered to help get the production and editing gear we needed. In fact, Marty overrode Film School protocols which restricted production gear to second-year students. Haig Manoogian, on the other hand, was not a major propagandist when it came to documentary films; his interest—which he imparted to his mentee, Scorsese—was the feature film.

Just to note: While Manoogian was not all agog about what we were pursuing, there was a previous generation of documentarians, like Leo Hurwitz of film and photo fame, and Amos Vogel, founder of Cinema 16 (author of the 1974 Film as a Subversive Art, devoting a section to our efforts), who eagerly lent comfort and support.

What put us firmly in the cross hairs of the intelligence snoops was a dalliance with the FBI at their uptown New York City headquarters. It was also destined to bring the spying experience downtown to NYU Film School (and by extension, to Scorsese and Manoogian)

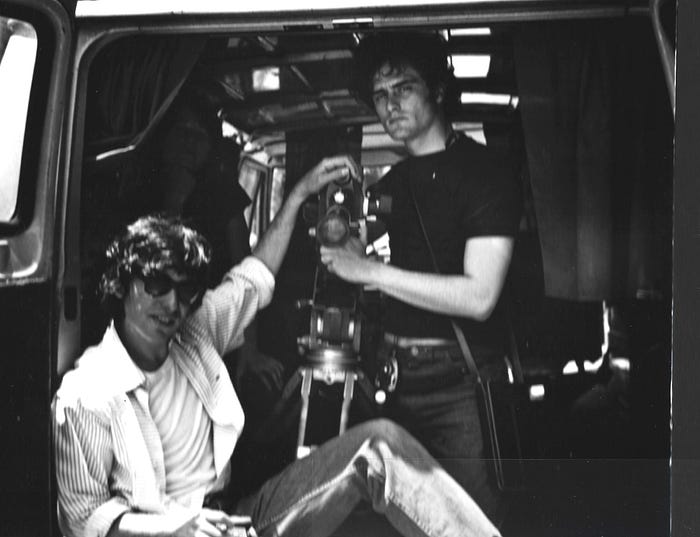

Now, knowing that setting up any sort of film apparatus on the corner of 69th Street and Broadway—FBI headquarters at the time—would be a honeypot attracting any number of snoops, we had two members of our group set up a tripod with a small Bolex 16mm camera.

In a van, parked close by, was the other half of our surveillance team with a hidden camera. Both members of our street crew were armed with wireless microphones which allowed for a total synch sound experience. So, with cameras rolling, the confrontation with FBI agents escalated and nearly exploded into fisticuffs as agents tried to block filming by standing in front of the Bolex (not knowing they were being filmed from inside our van). In an almost slapstick encounter, the FBI seemed flummoxed as Howard Blatt raised the tripod well above the offending agent’s head. It was blissfully hilarious.

As things cooled down, one agent—still unaware of the camera in the van—began to write down the plate number of the Volkswagen. Another could be seen taking a still photo of same. As our own surveillance van pulled away, one agent could be heard issuing a final admonition to Blatt, “you got studded tires, boy, they’re illegal.”

Amused they were not and, soon after, we were contacted by the NYPD’s Red Squad asking for a meeting. Yes, no problem, we gave them a time and place: directly outside of NYU’s Main Building on Waverly Place.

We kept Marty informed of the goings-on and, intrigued, he approved our use of Film School gear.

On the appointed day, the “bait,” so to speak, Howard Blatt, sat anxiously in his black convertible Volkswagen fitted out with a hidden Nagra tape recorder.

Across the street—on the second floor of Main Building—the rest of us hunkered down, scanning the street below. Pride of place—wedged in between us—stood a Film School-supplied tripod mounting a then state-of-the-art Eclair NPR.

Sure enough, two intelligence gumshoes —straight out of a 1940s detective drama—sauntered up. The well-known “face” of the Red Squad, Detective John Finnegan, was accompanied by a trench-coated FBI agent by the name of Slicks.

Finnegan—clearly, the lead in this interrogation—started to converse with the driver but quickly noticed the rest of us on the second floor.

“Is this your school project, or are you moonlighting? If I knew I was going to be filmed, I would’ve worn my makeup.”

Slicks, however, played deer caught in the headlights, exchanging nervous glances with Finnegan. Confused, he was trying to ascertain what was going on. Audio caught Finnegan explaining that this was NYU’s Main Building. After a bit of back and forth with Howie, and not getting the information they were seeking, they strolled off.

This exchange—caught on camera and audio—remains one of the highlights of Red Squad and still provokes a Keystone Cops response from viewers.

Later, we found out that Finnegan paid a solo visit to the Film School and spoke to Manoogian, and it seemed—from FOIA documents later recovered—found Manoogian scrambling for answers.

It seems that Manoogian did talk—nervously—but as far as we know gave nothing of value to Finnegan. As FOIA documents later revealed, he obviously did consult with Marty who, in turn, mentioned that we were doing a film about “constitutional rights.”

After all was said and done, we went our merry cinematic way without any interference by NYU administrators and with Marty continuing his support and encouragement.

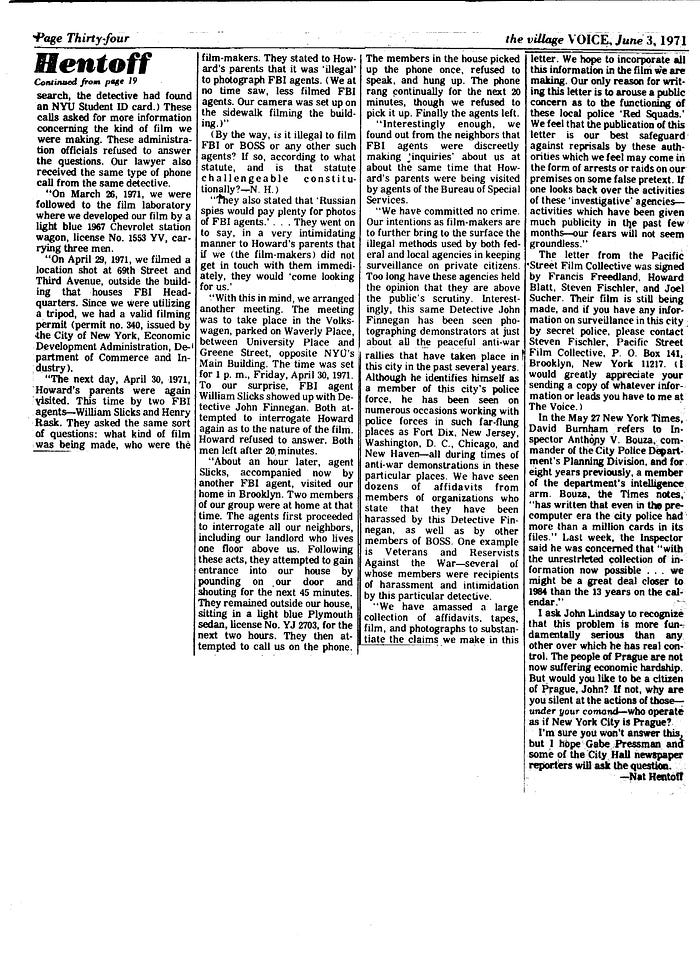

In the midst of all this, Nat Hentoff (RIP) got wind of our harassment and began chronicling the unfolding story in a series of articles for The Village Voice. We became central to Nat’s outrage at the city employing vast resources to try to stifle dissent. He laid blame at the feet of then-Mayor John Lindsay.

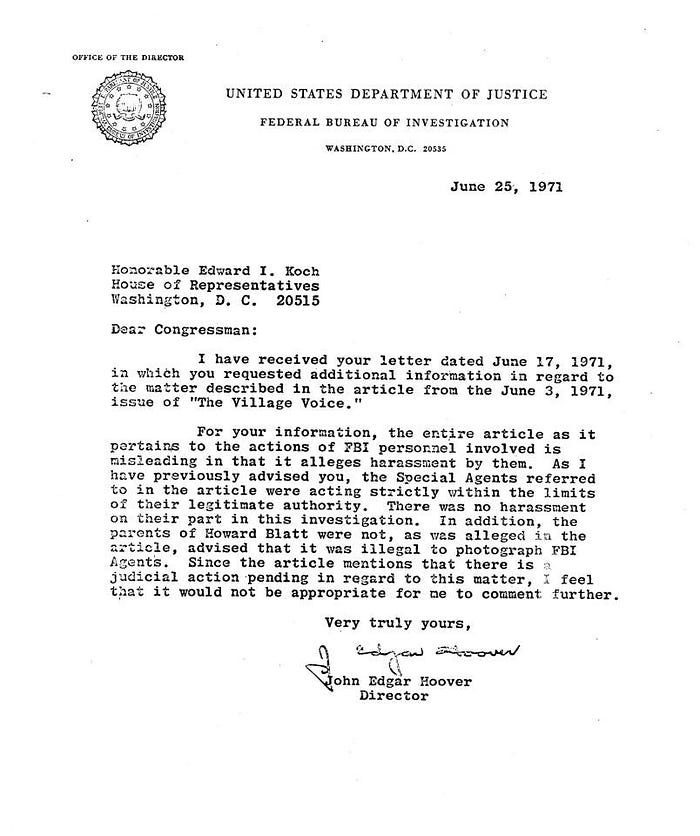

These articles, in turn, attracted the attention of then Congressman Ed Koch who, with dander fired up, shot an angry letter to—pause with a drum roll—J. Edgar Hoover.

Which brings me full circle to Killers of the Flower Moon and mention of the self-same J. Edgar.

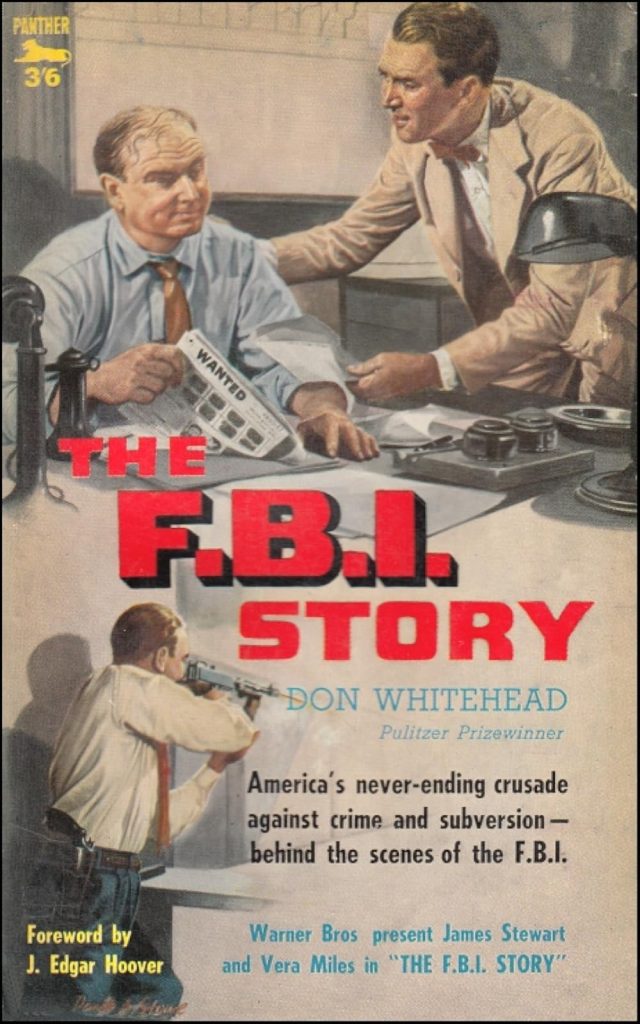

Hoover was a grandstander who worked the press tirelessly promoting the image of the FBI as infallible. Injecting himself as a “co-producer” into Hollywood features like 1959’s, The F.B.I. Story (where he appeared in a cameo), he made damn certain that no aspersions of any sort would appear on the screen.

The charade continued well after his death in 1972, with films like the 1988 Mississippi Burning—based on the 1964 murders of activists Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner—giving the impression that the Bureau stood squarely on the side of justice, ignoring the fact that the FBI—at Hoover’s behest—was committed to destroying those in leadership roles (including Martin Luther King, Jr.).

Today, of course, the tradition continues with promoters and cheerleaders like Dick Wolf spinning out made-for-TV blather, including franchises like FBI and FBI International.

While Killer’s Texas Ranger Tom White, according to the film, was pressed into the chaotic Bureau of Investigation to go after the bad guys, it begs the question: How closely did this skew toward reality?

Meilan Solly, in a Smithsonian piece, cites Killer’s author, David Grann:

Hoover and the bureau claimed they’d ended the Reign of Terror by arresting Hale and his accomplices. “The moment a couple of the killers were caught, Hoover wanted to close up shop, declare victory, and move on and use the case to burnish the reputation of the FBI,” says Grann. In truth, however, the conspiracy had a far greater reach than authorities acknowledged. Multiple murders remained unsolved, among them those of Whitehorn, McBride and Vaughan. Many more victims of the Reign of Terror had yet to be identified as such.

Whether Marty remembers—or takes seriously—his own run-ins with the agents of surveillance and whether he views this as a serious threat to “constitutional rights” is a question that none of his handlers has yet to answer.

Numerous requests for comment have been roundly ignored.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Joel Sucher is a co-founder of Pacific Street Films (together with Steven Fischler) and has written for a number of platforms including American Banker, In These Times, Huffington Post and Observer.com.

Joel can be reached at Pacific Street Films.

In his bid to secure the Democratic presidential nomination in 1960, Lyndon Johnson made use of Kennedy’s medical records to inform people of Kennedy’s illnesses.

The FBI would be the most likely source of that stolen information.

But Kennedy won the nomination and chose Senator Stuart Symington as his running mate. However, before the announcement could be made, Kennedy was forced to drop him and pick Johnson instead. Johnson was able to blackmail Kennedy using files supplied by Hoover.

This is just one example of J. Edgar Hoover’s sheer criminality.