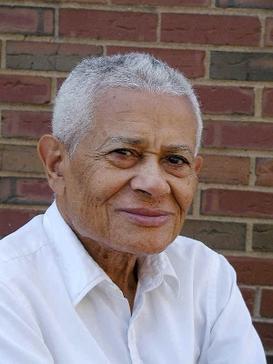

Blacklisted in the Cold War, Worthy reported on the struggles of Third World people against American neo-colonialism and on oppression within the United States

[In light of recent social media shutdowns of the pan-African media outlet, African Stream, we should take note of William Worthy’s great contributions and the ensuing repression. In roughly a two-week period, the Kenyan-based platform was summarily removed from YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Threads, Google, and even TikTok. Most of the closures came in September 2024 shortly after U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken told journalists “RT [Russian Television] secretly runs the online platform African Stream across a wide range of social media platforms.” He added, without providing a shred of evidence, that the site only gives voice to “Kremlin propagandists.”

Stanford University’s Internet Observatory/Cyber Policy Center joined in the contemporary red-scaring while advancing the prejudicial narrative that black people are incapable of thinking for themselves with an article titled “African Stream: Russia’s Latest Covert Influence Pipeline Targeting Africa and the U.S.”—Editors.]

Welcome to A Worthy Media.

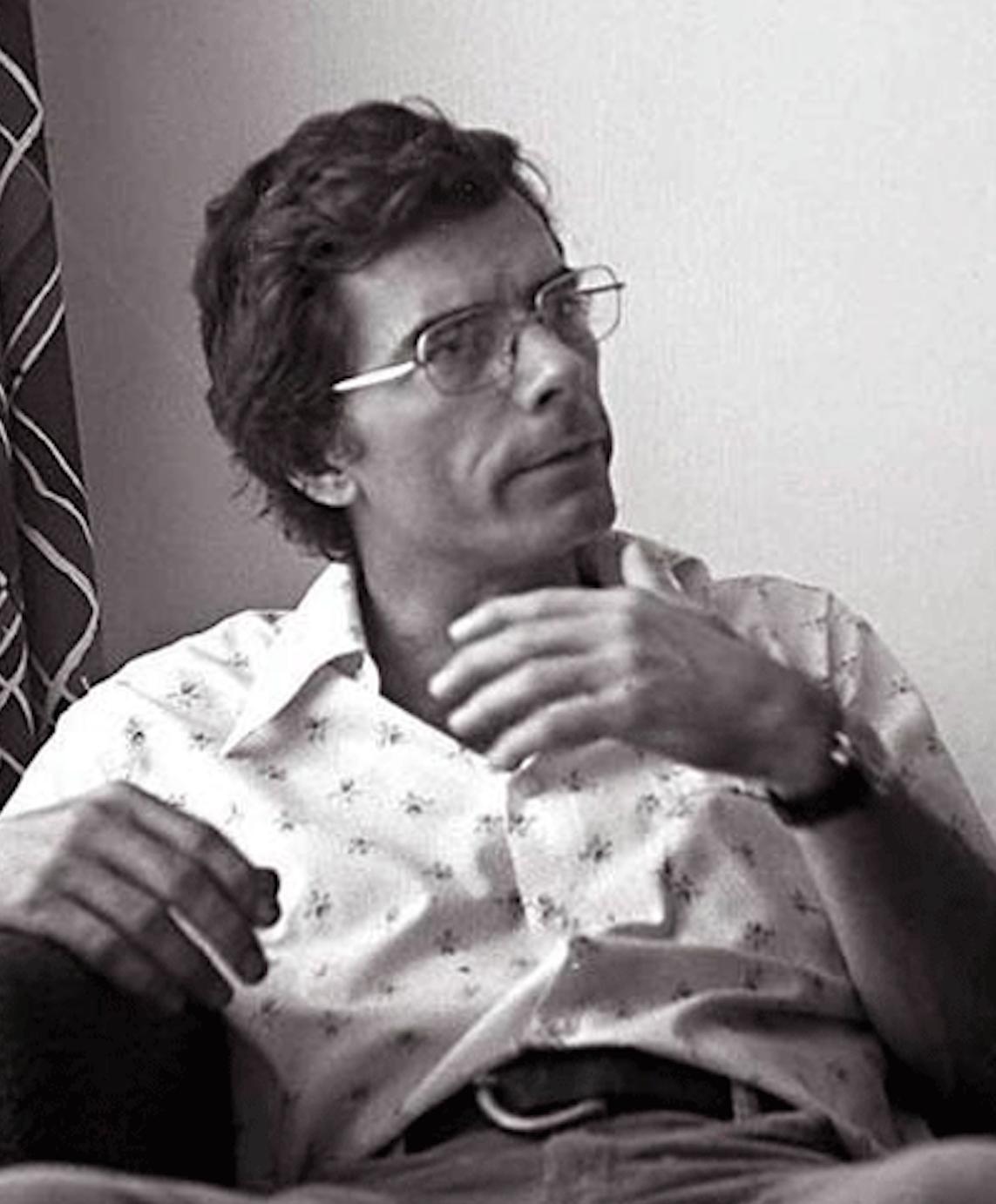

“In 1979, at the beginning of the Iranian hostage crisis, my passport was revoked…A few weeks after my passport was revoked, I received a letter,” said Philip Agee while facing a panel of lecturers at the Conference on the History and Consequences of Anticommunism at Harvard University in 1988. That letter was sent by “the revolutionary leader of Grenada, Maurice Bishop, which was an invitation to the first anniversary of the revolution.”

Included with the letter came a Grenadian passport. With Agee’s name and photo printed on the inside, the travel document would allow the former CIA case officer turned author of Inside the Company: CIA Diary and co-founder of CovertAction Information Bulletin (now CovertAction Magazine) to travel “all over Western Europe, Canada, Caribbean and so forth…until the invasion.”

Certain that his new passport would be rendered invalid once U.S. President Ronald Reagan installed a “caretaker government” following the execution of Bishop and some of his colleagues and a full-blown U.S. military invasion of the small Caribbean island in 1984, Agee, attending a solidarity conference in Nicaragua, explained his predicament to Sandinista officials. “’We’re going to give you a Nicaraguan passport,’” they assured him.

The title of this almost six minute YouTube video is “Philip Agee’s Revolutionary Passport” a testament to the role played by Grenada’s New Jewel Movement and Nicaraguan Sandinistas in furnishing a beleaguered CIA whistleblower with travel documentation. Commenting at Harvard, Agee pointed out that the denial of passports to “hundreds if not thousands” of U.S. citizens in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, was based on their “political beliefs and associations.” He cited two U.S. Supreme Court decisions that purportedly ended the practice. However, he went on to state that there were “others.”

In another video Agee mentioned one of those “others,” a journalist and U.S. resident, attempting to re-enter U.S. territory without a passport. That name, “Bill (William) Worthy,” did not ring a bell. I repeat—it did not ring a bell. Who was this fellow? How did he jar Agee’s recollection and understanding of his right to re-enter the United States without this coveted travel document? Years later, Democracy Now’s host, Amy Goodman, added another layer to the mystique with an obituary of Mr. Worthy headlined: “The Most Important Journalist You’ve Never Heard Of.”

With that, we take a look back to a time when: access to news articles and investigative journalism were not available at push-button internet speed; “content” had not been commodified alongside distractive, scroll-down social media feeds and the blazing discombobulation of a 24-hour, blood-rushing and eye-blurring breaking news cycle; media outlets were no less susceptible to and infected by, namely, the CIA, MI-5 and other propagators of misinformation, disinformation, and outright lies; but where individuals, families and communities, despite the pros and cons of technological simplicities of the day, still sought and found reliable means and resources to stay informed about what was going on in their neck of the woods and the world beyond.

As the title of this piece suggests, it was, without the multitude of tiny, shiny trinkets and gadgets that, in my view, keep far too many more detached, adrift and fearful rather than informed: its time for a worthy media.

Precursor

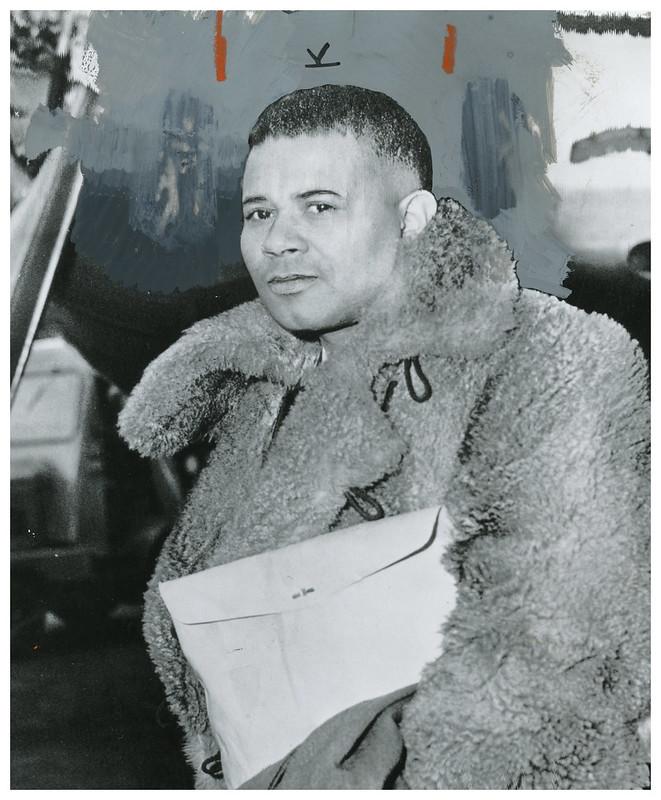

One lonely, intrepid soul, an international news correspondent who had traveled 1,300 kilometers, stood at a crossroad on December 24, 1956. Behind him flew the Union Jack, a flag, still reeking of opium and gunpowder, hoisted over Hong Kong since 1841. On the horizon was the small town of Shenzhen, located in China’s Guangdong Province.

Resuming his stride, it would not take him long to complete his crossing over the Luohu Bridge and, in doing so, become the first of his day. With the soil of Shenzhen firmly beneath him and with no other U.S.-based journalist ever having set foot in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), William (Bill) Worthy, reporting not for The New York Times but for The Baltimore Afro-American, would pioneer international news coverage of the Asian giant.

Turtles Think Turtle Thoughts

Informed to a lesser degree by the rubric of “objectivity”—a career-ending quality if he were, let’s say, reporting on-the-ground from 1930s or ’40s Nazi Germany—Mr. Worthy based and balanced his reporting on keen observation and intimate experience. In shaping his coverage, he developed a narrative insightful and empowering to his community and beyond.

“Colored visitors from the (United) States,” Worthy wrote, “find themselves peering at institutions and social relations in a one-track effort to determine whether life there would mean an end to the haunting self-consciousness of dark pigmentation.” Furthering his query, he noted that China, having “deported or jailed the white top-dogs of yesterday” could serve as “a mecca for half the population of Mississippi and all the residents of Harlem.”

Proceeding to travel across China, Mr. Worthy scored interviews with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and other top officials, as well as William C. White, Samuel David Hawkins, and a Black former prisoner of war, all of whom refused to be returned to the U.S. following the Korean War.

By publishing unrivaled reports of the day, Worthy’s coverage served not as de-contextualized soundbites but in-depth, social-investigative journalism, an extension of pedagogic work, producing articles and essays to keep a well-informed global citizenry then and to this very day.

One reader of his column, an eighth-grade dropout and former prisoner, was indulged by Pulitzer Prize laureate, author and historian, Arthur Schlesinger. Attempting to trick the flunky and ex-inmate proved futile, unbecoming of the celebrated academic. Instead, his interviewee, a global figure now popularly known as Malcolm X, clarified that so-called criticisms Worthy had leveled against the Nation of Islam was not a rebuke of the organization, rather condemnation of the human rights abuses perpetrated by the United States against the Black community in which the entity had no alternative but to emerge.

Before being showered with literary and academic accolades, Schlesinger cut his teeth at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the CIA. Acquainted with Allen Dulles, the first director of the CIA, Schlesinger was invited to serve as an Executive Committee member for Radio Free Europe, a media outlet secretly established by the CIA following World War II. (The National Committee for a Free Europe was the front organization that maintained the CIA’s confidentiality in operations too many to count across Europe post-WWII).

Mr. Worthy’s body of journalistic work and the number of risks he tallied during his illustrious career during the height of the Cold War is a far cry from the gossip-commodity extravaganza and brazen propaganda published by large portions of the Western media halo.

Echoing the vast amount of hype written in opposition to countries deemed enemies by U.S. authorities and their allies, editors, media pundits, and talking heads, it becomes a task in itself to ascertain whether the extraordinary number of likes, thumbs-up, shares, and views are more Silicon Valley AI bots than actual people, although actual people do voice these sentiments. To quote Mr. Worthy, and here he is not referring to social media but The New York Times, “The Times realizes the American public is so gullible and so poorly educated they can get away with such blatant advocacy.”

En route to China

William Worthy’s crossing over the Luohu Bridge from Hong Kong into Mainland China in the final days of 1956 came at an enormous personal and professional risk. At the time, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was attempting to break an information containment and isolation campaign imposed by the U.S. government.

The effort dated back to October 1950, when China dispatched a “People’s Volunteer Army” to assist Korean troops based in the north in their struggle against Korean soldiers situated southbound and supported by imperialist Yankee forces. In response, officials in Washington immediately banned U.S. citizens from traveling and transferring money to China. Responding to these measures, Chinese officials initiated a campaign to expunge their homeland of any and all “American-loving,” “American-fearing,” and “American-worshipping” sentiments. In doing so they outlawed American movies, music and radio stations, as well as transferred control over all U.S.-funded educational and cultural institutions to Chinese administrators, expelling most Americans working at these organizations.

Hostility between the two countries would persist well after the armistice signed at the unofficial end of the Korean War in 1953. The remnants of that conflict exist to this day, delineated by the demilitarized zone, severing Korea into North and South at the 38th parallel zone.

Talks to rebuild trust and resume cultural and trade ties between the U.S. and China were initially stymied in 1954 and 1955. During this period, aiming to obtain the release of all their military personnel and citizens detained in China during the Korean War, the U.S. officials agreed to open direct negotiations with their Chinese counterparts. If William C. White, Samuel David Hawkins, and a Black former POW were even included on the release list, they did not abide by the resolution, remaining in Asia to live their lives.

However, when China declined to release all U.S. detainees before resuming further negotiations, Washington refused to proceed with talks on more “substantial issues” such as the political status of Taiwan. In 1972, nevertheless, China and the United States released a joint communiqué stating the latter “acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China.”

With no end in sight to the gridlock, China opted for direct people-to-people exchange. Eighteen U.S.-based journalists, with New York Times reporter Harrison Salisbury leading the bunch, were invited to visit the country for one month. Worthy’s name, along with Associated Press (AP) correspondent John Broderick and others were included on the list.

Not in Whose Interest?

On August 7, 1956, the U.S. State Department responded to China’s invite, stating in a press release that the government agency would “continue not to issue passports for travel to China.” The department added “it is not considered to be in the best interests of the United States that Americans should accept the Chinese Communist invitation to travel in Communist China.”

Despite the notification and subsequent warnings, U.S. authorities grew increasingly worried that their message was falling on deaf ears. The AP went so far as to inform the U.S. State Department that Broderick would accept the Chinese invitation as the interests of the media outlet “were not similar to those of the Department.”

Faced with a compliance breakdown, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower intervened, releasing a statement on August 20, 1956, in support of the State Department’s wishes.

Most media outlets and their journalists backtracked immediately. While NBC reporter James Robinson said “one does not lightly defy the President,” his high-profile New York Times counterpart, Salisbury, similarly buckled, informing China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) that his trip to the country was effectively canceled.

But Mr. Worthy? Having visited and reported on the Soviet Union and interviewing the country’s leader, Nikita Khrushchev, in 1955, without U.S. State Department permission, he, an “Anti-Colonialist” and “Anti-Imperialist,” reporting for the small, yet trailblazing Baltimore Afro-American weekly newspaper, had no qualms bucking Uncle Sam.

Operating as head of his own Ministry of Foreign Affairs, prior to crossing the Luohu Bridge, Mr. Worthy petitioned China’s MFA Media Division to allow him to enter the country a few days prior to any other journalist. “Rarely,” he explained, are Black journalists at the “points of major international news.” He emphasized that Black media houses established and operated by his people lack “sufficient financial resources to keep a corps of correspondents stationed permanently abroad” and by allowing him first dibs at reporting on China would serve as “prestige of the Negro Press.”

With his official request approved, Mr. Worthy would go on to spend 41 days reporting on-the-ground from China.

Reactionaries Work Double-Time

U.S. State Department officials were livid. They were livid even before Mr. Worthy’s diplomatic prowess and subsequent arrival in China.

“The ban on travel to China mainland will collapse rapidly, as he [Mr. Worthy] will be followed by a stream of other correspondents and probably also missionaries, scholars, and others,” wrote Ralph N. Clough, a ranking member of the U.S. State Department’s Office of Chinese Affairs. In the memo addressed to the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State, Walter Robertson, Clough outlined three recommendations to rein in Mr. Worthy’s international reports.

They included: restrictions imposed, effective immediately, on the use of his passport via the U.S. consulate in Hong Kong and U.S. Embassy in Moscow, thus preventing him from traveling anywhere in the world except to the United States; request Mr. Worthy’s bank assets be frozen, effective immediately, by the U.S. Treasury Department; or initiate litigation against the journalist by the U.S. State Department’s legal team.

Upon his return from China, U.S. officials confiscated the passport they had issued to Mr. Worthy. Eleven years would pass before he was provided with a replacement. However, during the decade-plus-long period free of a Yankee passport, Mr. Worthy’s international diplomacy skills were not impeded, allowing the seasoned journalist to visit Indo-China, Cambodia, and even North Vietnam to report on the War Against the Americans to Save the Nation.

In 1960, still relieved of travel documentation, Mr. Worthy boarded a ship heading to Mexico. From there he proceeded to Cuba where, just weeks after the failed Invasion of Pigs, he interviewed Fidel Castro and co-produced a TV documentary titled “Yanki, No!”?

Upon his return to the United States, Mr. Worthy was detained by U.S. State Department officials and sentenced to three months in prison. His crime: attempting to enter the U.S. without a passport. Remember Philip Agee?

“White citizens who have come home without passports have never been prosecuted,” wrote members of the Committee for the Freedom of William Worthy to U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy in 1962. The judicial case—Worthy v. United States, 328 F.2d 386 (5th Cir. 1964)—aroused international attention and was eventually overturned, unanimously, by a federal appeals court.

In 1964, folksinger and guitarist Phil Ochs released the “Ballad of William Worthy,” a tribute to Mr. Worthy’s uncompromising journalism. Ochs, himself, would travel to Chile in 1971, where he befriended fellow musician Victor Jara, a staunch supporter of Marxist President Salvador Allende, who was democratically elected the previous year. Performing in the Southern Cone of South America during regional military dictatorships, Ochs was detained in Uruguay, Argentina and Bolivia. Similar to other musicians—Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon, Yusuf Islam (formerly Cat Stevens), Aretha Franklin, Tupac Shakur, and Nina Simone to name a few—the FBI had compiled a file on Ochs containing nearly 500 pages.

Twenty years later, in 1981, just two years after the triumph of the Iranian Revolution, Mr. Worthy traveled to Tehran. During his stay in the capital he obtained a large cache of formerly secret CIA documents outlining carefully crafted manipulation of Iranian politics pre-dating the 1953 overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. The documents had been meticulously reassembled from piles of paper shredded by U.S. diplomats as they rushed frantically to destroy evidence before the taking of the U.S. embassy by Iranian students and revolutionaries in 1979.

This time, upon Mr. Worthy’s return to the United States, FBI agents immediately seized a large chunk of the CIA files, deeming his possession of them as a “serious intelligence breach.” Following suit, the U.S. Justice Department threatened to bring charges against him for possessing “classified documents.” Once again, Mr. Worthy found himself on the hot seat. But in classic fashion, the experienced international journalist and seasoned ambassador, on behalf of himself and his nation within a country, told Amy Goodman in a 1998 interview that he “never lost a wink of sleep over it.”

Again litigation, this time against the FBI and CIA, ended in Mr. Worthy’s favor. He and his colleagues were awarded $16,000 in damages by U.S. officials who had acted illegally.

Memories of a Worthy Media

In 1898, Liang Qichao set sail from China en route to Japan. Wanting to distance himself from milquetoast political reforms known as the Hundred Days’ Reform during the Qing Dynasty, as well as internal weaknesses, ongoing economic and social unrest in the wake of two opium wars, the Sino-French War, the Sino-Japanese War and other imperial interventions, Liang preferred exile to the status quo. His journey, in some ways, mirrors that of Worthy’s travels some 60 years later.

Once in Japan, Liang would establish himself as a journalist, editor, and newspaper founder. Publishing articles that spoke to the spirit of the Chinese people, particularly the youth, envisioning and calling for a brighter future for his nation—“the red rising sun will light up the road ahead”—Liang became known as the Father of Modern Chinese Journalism.

“The spirit of the youth was what we lacked and desperately needed,” Liang wrote in his seminal essay “The Young China”: “On the one hand, I was really disappointed at the then ruling class, so stubborn and narrow-minded. On the other hand, I have such great expectations of the younger generation. The youth are the holders of the future. Proper education for the youth should include more education, intellectual education and emotional education so that they would be free from confusion, worry, and fear. If the young are free, the nation becomes free. If the young progress, the nation will progress.”

In more than 400 letters written to his nine children, Liang, co-founder of the Imperial University of Peking, now Peking University, espoused intimate details about one’s pursuits and goals. “As for the fact that you did not get into college is the least important,” he told one of his children. “You’re there to gain knowledge not to grab a diploma.”

Although Liang would not live to see the Chinese people emerge from wars and battles against imperialist interventions, sickness, drug addiction, and backwardness, through the years, his legacy would be upheld by future journalists, with William Worthy joining the tapestry decades later.

Worthy Credits

From 1953 to 1980, Mr. Worthy reported for The Baltimore Afro-American. During this period, he also filed articles and essays for The Boston Globe, New York Post, and CBS News. He was also the author of the book The rape of our neighborhoods: and how communities are resisting take-overs by colleges, hospitals, churches, businesses and public agencies.

Mr. Worthy taught journalism courses at Howard University, University of Massachusetts Boston, and Boston University. He was removed as head of the African-American journalism program from the latter institution for supporting unionizing efforts by campus workers.

Over the years Mr. Worthy received several press freedom awards and, in 2008, Harvard’s Nieman Foundation presented him with the Louis M. Lyons Award for Conscience and Integrity in Journalism. “Throughout his life in journalism,” said Bob Giles, then-Nieman Foundation curator, “Worthy demonstrated a remarkable spirit of courage and independence in his determination to inform readers about places our government wanted to keep hidden from public view.”

Shortly after Mr. Worthy passed away in 2014, Amy Goodman aired a TV obituary titled: “The Most Important Journalist You’ve Never Heard Of.” In retrospect, Mr. Worthy was a rather household name among his community and members of the international community. Thank the hollowed-out media mill, a matter of conformist hue, select rainbow representation, and a massless fog of emotion if you were unfamiliar with or haven’t even heard of his name. For Worthy, as far as “early entrapment in U.S. racial culture” is concerned, it belittles while underdeveloping society, seeing “only what is already in our eye” and learning “only what we are already inwardly prepared to accept.”

In his later years, Worthy warned of this growing fallacy, one that infects the mainstream media of today. “If in the 1990s, a U.S.-led relapse into Kipling’s white man’s burden seems wholly implausible, check back to April 18, 1993, when The New York Times Magazine published an astounding article headlined “Colonialism’s Back—and Not a Moment Too Soon,” with the subhead “Let’s face it: Some countries are just not fit to govern themselves.”

Although more than half a century has passed since Mr. Worthy set foot in Shenzhen, now a prosperous economic hub and special economic zone, his reporting keeps thwarting the apple cart.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com

I will never forgive the gang that relieved us of the best high school music teacher I have ever had or could expect to meet in a lifetime. You see, he was black, liberated and anti-fascist. He introduced us to Marion Anderson and Aron Copeland and James Weldon Johnson and Emma Lazarus and we sang a type of music called Level Six, that was the best any high school chorus could do. So he was my teacher in 1961 and 1962 in an upstate NY high school, and the next year (junior year) he was gone. Never had I missed a teacher more. I called him up from my post at the telephone company to thank him shortly after I graduated, and actually got away with it. My strike-out for freedom I guess. He was so fine. Kind of a hero to me. Probably some of the parents caught wind that he was solidly leftie and I guess in those days that stuff was enough to blacklist any such renegade. UNFORGIVABLE. I have never told this story to anyone all these long decades since then, until now. Thought it was time. Yes such virulent hysterical political abuse cut THAT deep. I can’t believe he would have just “quit”.