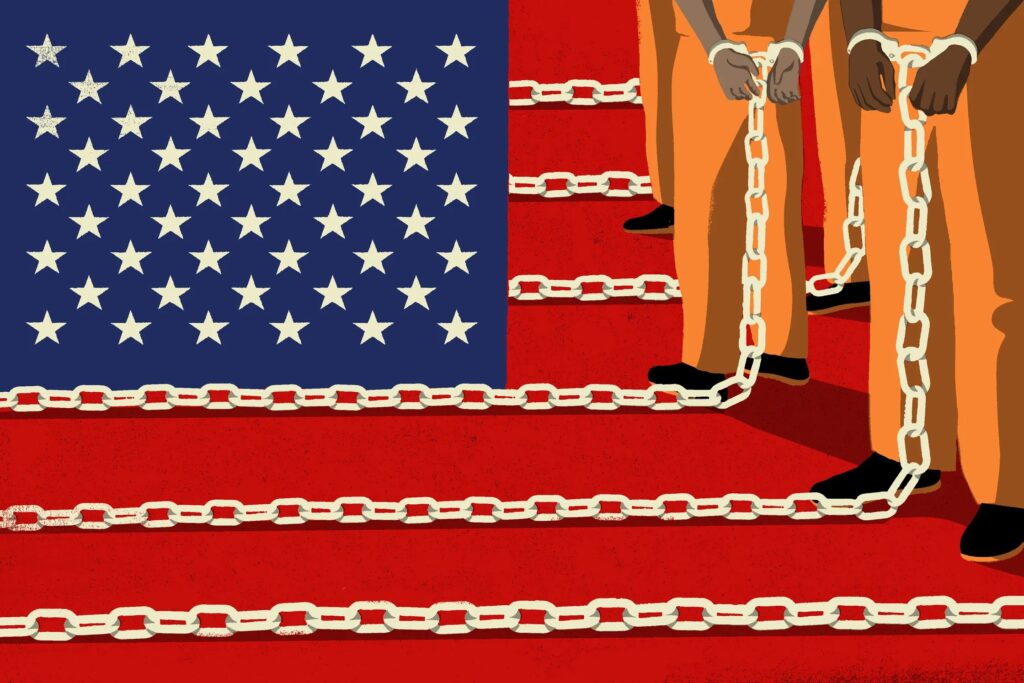

The United States today has by far the world’s largest incarceration rate, with nearly two million people living in prisons and jails.

The conditions in those facilities are often substandard, with Amnesty International criticizing the dehumanizing practice of holding prisoners in prolonged solitary confinement.

Benjamin Weber’s book, American Purgatory: Prison Imperialism and the Rise of Mass Incarceration, shows that mass incarceration and inhumane prison conditions emerged as a counterinsurgency strategy for pacifying Native Americans and keeping the Black population in check. U.S. leaders set up draconian prison apparatuses in colonial domains, like the Philippines, with the new forms of social control migrating home.

An assistant professor of history at the University of California at Davis, Weber writes of an “unspoken doctrine of prison imperialism” by which U.S. policy makers sought to “govern the globe through the codification and regulation of crime.”

Weber adds that, “as prison imperialism expanded outwards, it always returned home producing new forms of social control over the growing number of people ensnared in prison in the United States….The forms of policing and record keeping that gave rise to the surveillance state between World War II and the Cold War were pioneered through overseas colonialism, covert operations and military interventions.”[1]

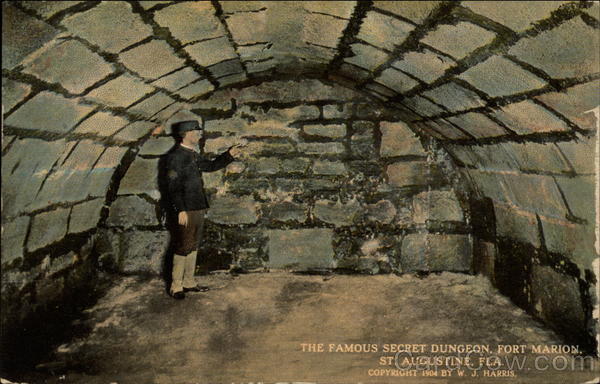

Weber’s first chapter provides a history of Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine, Florida, an infamous prison where Black and Indigenous people were held captive. According to Weber, the prison represents a “cornerstone of U.S. prison imperialism,” revealing the “colonial roots and global dimensions of the U.S. carceral state.”[2]

By the 1730s, Florida’s panhandle had become home to a growing band of Black maroons, fugitives from slavery who integrated themselves with the Seminoles, the most powerful people in the region prior to the Spanish and British imperial conquests.

Hundreds of maroons lived in a Black fort on Prospect Bluff where they forged a productive community that had an extensive trading network.

Characterizing Prospect Bluff as a “hornet’s nest of bandits, outlaws and pirates,” the U.S. military launched a preemptive strike in 1816 under the orders of Andrew Jackson, whose men incinerated hundreds of the maroons and triggered the Seminole Wars which lasted for decades.

In 1837, the U.S. military took Seminole chiefs Osceola and Coacoochee (Wild Cat—the son of King Philip) prisoner in Castillo de San Marcos (renamed Fort Marion prison), which had a 30-by-20-foot dungeon and torture chamber with a rack for suspending prisoners from the wall.[3]

Fort Marion was later used to house Indian prisoners from the Western Plains and Apache prisoners taken from the Arizona Territory. Among them were 100 Apache children who were transported to the infamous Indian residential school at Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania where their culture was eviscerated.[4]

In the early 19th century, James Monroe proposed to Thomas Jefferson the creation of a penal colony where Blacks involved in slave revolts could be permanently banished.

The idea was later supported by Abraham Lincoln and reinvigorated in the Jim Crow South when criminologists proposed sterilization of Blacks as a way to prevent crime.

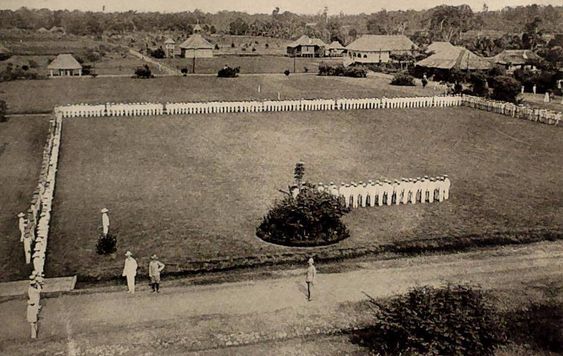

When the U.S. colonized the Philippines at the turn of the 20th century, mass incarceration became a linchpin of counterinsurgency strategy.

It was designed to suppress the nationalist rebellion and messianic peasant leaders like Felipe Salvador, a leader of the anti-Spanish resistance who was arrested by U.S. authorities on charges of sedition and sent to Bilibid Prison in Manila.[5]

Colonial officials under Police Secretary W. Cameron Forbes,[6] a former Harvard University football coach and investment banker, studied prisoners at Bilibid so they could better control them, and instituted forced labor regiments in order to create a “spectacle of degradation.”[7] Forbes believed that “jail must be made a very real and awful thing to the criminal classes.”[8]

To give off a benign appearance, reformed prisoners were transferred to the Iwahig Prison and Penal facility on Palawan Island, a 100-acre plantation where inmates grew their own food along with cash crops for export, engaged in self-policing, and could in certain circumstances bring their families and live in nearby cabins.

Iwahig was modeled after the George Junior Republic, a reform school for delinquent boys in Upstate New York that sought to create a nurturing environment while instilling discipline and a strong work ethic.[9]

Superintendent John White believed that a year or two at Iwahig “in a semi-free, hard-working, agricultural community has excellent moral and physical effect.” Criminologist John P. Gillin characterized his visits to Bilibid and Iwahig as “moving from certain hell to kingdom come.”[10]

A key goal was to coopt the Philippines nationalist movement and to get its leaders to support the U.S. colonial state—much like defector and amnesty programs in the Cold War.[11]

When the U.S. began building the Panama Canal, mostly Black prisoners were put in road gangs and forced to build up the zone’s roads and other infrastructure under hellish conditions.[12]

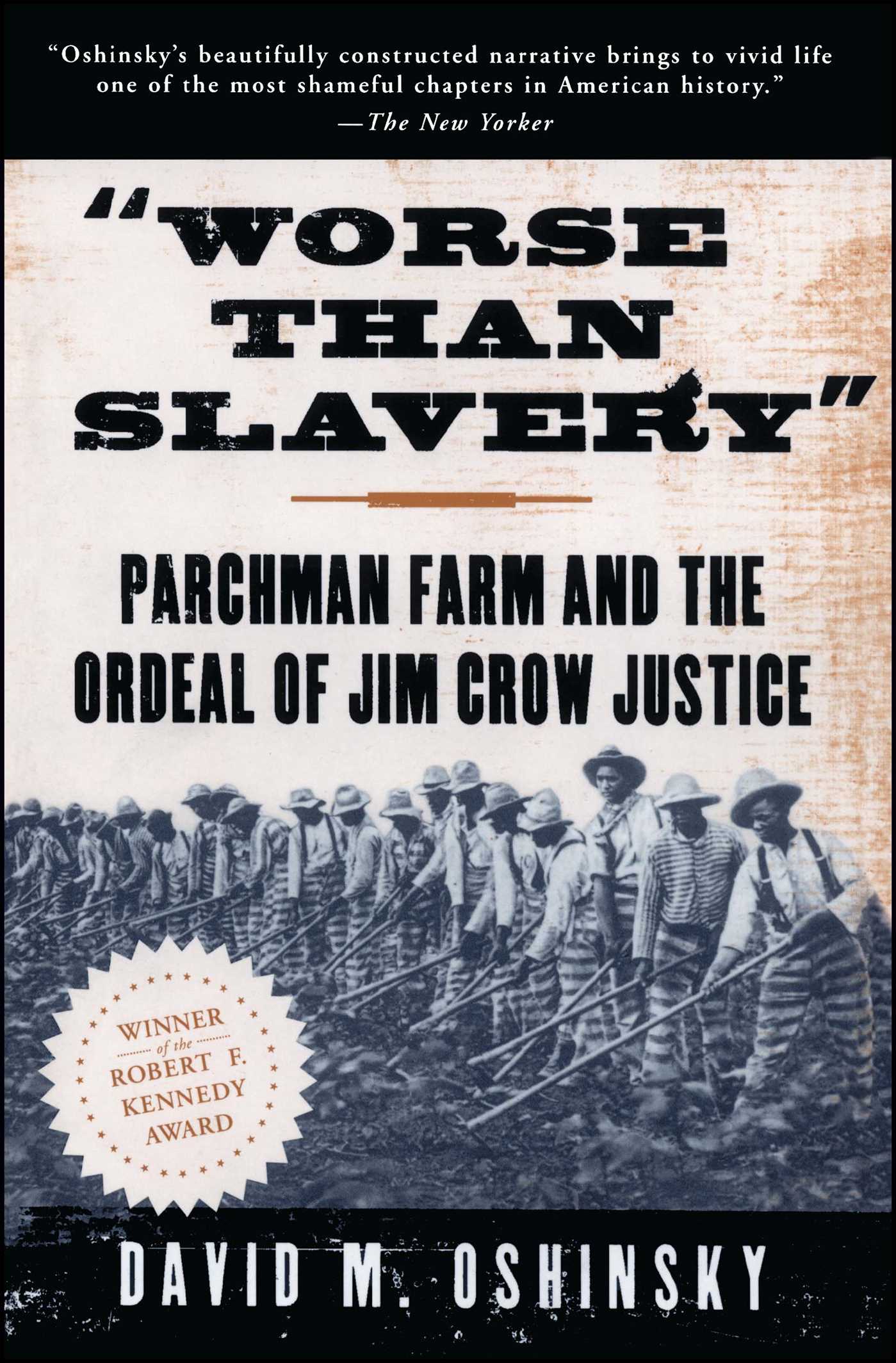

The treatment of prisoners in the Panama Canal Zone mirrored the convict leasing system in the Jim Crow South, where primarily Black inmates were rented out to private companies to perform manual labor for a slave wage.

Historian David Oshinsky referred to Jim Crow prisons as “worse than slavery” because, under slavery, the master was intent on protecting the health of his investment and not over-working him too much; whereas, in the Jim Crow prisons, harsh Black Codes ensured a ripe supply of prisoners, meaning that the existing ones were easily replaceable.

Reformers in the late 19th century heralded the McNeil Island penitentiary in Puget Sound off the coast of Washington State as a prison of the future, though it had a black hole dungeon where convicts were suspended in chains by the wrists and manacled to the wall if they refused to work.

This kind of treatment resembled that of inmates at Alcatraz, the notorious Devil’s Island prison in San Francisco Bay where problem prisoners were confined to “coffin cages,” 23 inches wide by 12 inches deep.

In his memoir, Philip Grosser, a conscientious objector to World War I who was placed in the “coffin cage” for two months, said that, when he entered the prison, guards told him that he and other conscientious objectors were not “white men anymore but yellow men” and “inscrutable Orientals” and that they would treat them as such when they broke the rules.

These comments epitomize the racist nature of the U.S. penal system that persists to this day. Weber emphasizes that the racial hierarchies and oppressive treatment of captives in colonial wars and inmates in colonial enclaves helped shape the mistreatment of minority groups and left-wing subversives in U.S. jails throughout the Cold War period and beyond.

The modes of counterintelligence adopted in colonial environments were routinely deployed against Black and Puerto Rican movements for self-determination within U.S. borders and on the island of Puerto Rico. In many cases the leaders of these movements found themselves incarcerated under fascist-like anti-sedition laws modeled after ones used to repress the Filipino nationalist movement.[13]

Protests against prison imperialism coalesced with the occupation of Alcatraz from 1969 to 1971 by leaders in the American Indian Movement (AIM), and more recently, with the “In the Spirit of Mandela” campaign launched in 2017 by former Black Panther Jalil Muntaqim from inside a prison in New York with the goal of convening an international tribunal to investigate violations of U.S.-held political prisoners’ human rights.[14]

The Spirit of Mandela campaign has coincided with efforts of Black Lives Matter to topple statues of Andrew Jackson, one of the original architects of prison imperialism. His white supremacist ideology lives on among pro-Trumpers and other overseers of the American prison system, whose abusive practices have deep historical roots.

Benjamin D. Weber, American Purgatory: Prison Imperialism and the Rise of Mass Incarceration (New York: The New Press, 2023), xi. St. Augustine is considered America’s oldest city, having been built by the Spanish in 1565. ↑

Weber, American Purgatory, 1. ↑

Weber, American Purgatory, 3. Coacoochee succeeded in escaping. ↑

These children included Apache Chief Geronimo’s daughter, Ih-Tedda. Geronimo was taken to another prison in Florida after authorities broke a promise to him that he and his men would not be separated from their families.

Weber, American Purgatory, 74, 75. ↑

A Boston Brahmin whose grandfather was Ralph Waldo Emerson and whose father was president of the Bell Telephone Company and made a fortune trading in China, Forbes served as Governor-General of the Philippines from 1909 to 1913 and U.S. Ambassador to Japan from 1930 to 1932 after being appointed by President Herbert Hoover. ↑

Weber, American Purgatory, 77. ↑

Weber, American Purgatory, 119. ↑

Weber, American Purgatory, 120. ↑

Weber, American Purgatory, 119. ↑

See Jeremy Kuzmarov, “Under the Façade of Benevolence: Psy-Wars, Amnesty and Defectors in America’s Asian Wars,” The International History Review, September 4, 2019, https://jeremykuzmarov.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/psywararticle.pdf ↑

Weber, American Purgatory, 86. ↑

Weber, American Purgatory, 144. ↑

Weber, American Purgatory, 195. Muntaqim was charged with killing two NYPD officers. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.

Absolutely true. Author Alfred McCoy did heck of a research on this subject as well through his book, Policing America’s Empire.

Here is some recent news from Syria:

https://www.france24.com/en/middle-east/20250111-syria-s-forced-disappearances-no-relief-for-grieving-families