China’s future looks increasingly bleak, but it has great counter-cyclical expansion potential via domestic and international rebalancing

In a daring thought experiment, imagine just for a moment that you are the powerful president of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). You are sitting next to a cozy fireplace in a mountain retreat, looking out of a panoramic window and musing about the “Central Kingdom.” What is your sweeping vista of China’s current standing and what future do you envision for this dragon beyond the distant summits in a rapidly changing world, where conventional truth is apparently being pulverized at lightning speed?

1. Current Situation: Domestic and International Troubles

At first sight, my dear president-in-thought, I admit that you could get easily depressed. Domestically, China has not fully recovered from the dystopian Covid-19 pandemic. The government is likely to have missed its growth target in 2024, with GDP projected to have increased by only 4.8% in that year. Even though many countries can only dream of such a solid economic performance, this figure pales compared to an average growth rate of more than 9% since the start of the Reform and Opening policy in 1978.

China also faces tremendous internal structural problems, such as sectoral challenges in real estate, high youth unemployment and a worsening dependency ratio due to an aging population. Moreover, foreign direct investment into China is trending downward, having declined by 30.4% in the first three quarters of 2024 compared to the previous year. Put in a nutshell, the stellar assent of the Central Kingdom since 1978 seems to be halted, at least for the moment.

To make things worse, mighty storm clouds are gathering quickly in the international arena. Increasingly, the so-called Collective West is singling out China as its strategic enemy number one—a radical shift compared to the previous exuberant Sino-euphoria that culminated in a veritable China-mania, with Western bosses trying to outsmart each other when it came to giving favors to the Central Kingdom. Back then, one of the greatest fears of a typical CEO of a Western multinational company was not to go down in history as the company’s leader who missed China.

Now, apart from a military build-up in the West that is directed against China, in the economic sphere, a ferocious trade war with the United States is looming. For example, President Donald Trump promised a tariff of up to 60% on all goods imported from the Central Kingdom. Even long before being inaugurated, he announced that, on his first day in office, he would start by singling out China, which will need to pay an extra 10% on top of all the new tariffs he is going to impose on other countries.

This forebodes a significant drop in China’s net exports (the difference between exports and imports), which are an important driver of demand-side GDP growth. To start with, the reason for the decrease of exports is simple: Chinese exports to the U.S., which account for 15% of China’s total exports,[1] will become more expensive for American buyers, which is likely to lead to a decrease in demand for them. If China’s imports do not drop as sharply as exports (possibly because many imported goods are vitally important to its economy), net exports will decrease.

Moreover, in its very front yard, North Korea, an important traditional ally of China, appears to be pivoting to Russia as its next key partner. This shift forms part of the megatrend of global realignment after the start of Russia’s Special Military Operation in Ukraine in 2022, with Russia looking for new allies in the face of severe sanctions imposed by the Collective West.

Not surprisingly, bearing in mind the manifold and grave domestic and international challenges, the future of China looks increasingly bleak to many observers, with China resembling a boxer who has received several blows and is tumbling.

2. The Road Ahead: Balance As a Key Guiding Principle

In every crisis, there is upside potential for success, to be achieved by making nuanced and decisive distinctions. After all, the Chinese character for crisis contains two parts, that is, wéi (危), which stands for danger, and jī (机), which signifies opportunity. Moreover, in ancient Greek, the word krísis (κρίσις) literally denotes an act of separating and by extension a decision.

Leveraging these cross-cultural philological insights as mental and spiritual inspirations, the Chinese president can use the critical juncture to make important counter-cyclical distinctions and steer his ship of state into an opportunity-rich direction. The key to success is a smart and delicate balancing act at home and abroad in the service of various stakeholders in the national and global socio-economic ecosystem.

In this regard, the outside challenges in particular—rather than being harbingers of doom—can serve as powerful catalysts to bring about the necessary transformation because they tend to imbue decision-makers with a strong sense of urgency. As a rather ironic unintended consequence, the hostile agenda of China’s powerful external enemies, thus, may well become confounded.

a. Domestic rebalancing: from investment to consumption

As an initial step, China’s leader should sharpen his focus on transformative domestic policies, strengthening China internally and, thus, improving its ability to resiliently cope with crises induced from the outside. The main leverage point in this regard is restructuring the composition of GDP from investment-driven to consumption-driven growth.

Out of the four components of GDP calculated by the expenditure method on the demand side of the economy—that is, consumption, investment, government expenditure and net exports—the key driver of China’s economic miracle after the start of the Reform and Opening policies was investment, funded by an above-average domestic saving rate.

In recent times, this particular growth engine has become problematic, though, mainly due to the following factors: First, there are declining marginal returns on every extra unit of investment. Furthermore, according to the so-called Solow growth model, depreciation increases when the capital stock rises. This can potentially lead to a point beyond the steady-state level of capital where depreciation will be higher than investment, which means that the capital stock will actually decrease.[2] Moreover, the Solow model shows that, in the long-run equilibrium, the growth of income per worker is not driven by capital and labor, but only by the rate of technological progress,[3] all of which are supply-side factors.

Moreover, high investment comes at the expense of domestic consumption, which is significantly lower than in many advanced economies. In contrast, rebalancing GDP toward higher consumption inside China, ceteris paribus, would imply that Chinese citizens would come to enjoy to a greater extent the fruits of economic growth. Important policy tools for bringing about such a shift include tax cuts and transfer payments to consumers. While China tried to promote domestic consumption at certain points in the past, more efforts need to be undertaken in this respect in the future.

As we have seen, the key to sustainable increases in living standards in the long run is rising productivity due to technological progress on the supply side of the economy. In this regard, the Chinese president should embrace innovative private entrepreneurs who in recent years to some extent, have become the lightning rod and scapegoat for many of China’s socio-economic problems. In particular, it should be recalled that the art of Chinese management practiced in the private sector explains much of China’s economic miracle, as demonstrated by rigorous empirical research.[4] Among other things, the stellar performance of the Central Kingdom resulted from the high rate of innovation achieved by private enterprises, which is an important driver of technological progress. Apart from the domestic opportunities, possibly even greater untapped counter-cyclical expansion potential lurks in the international arena.

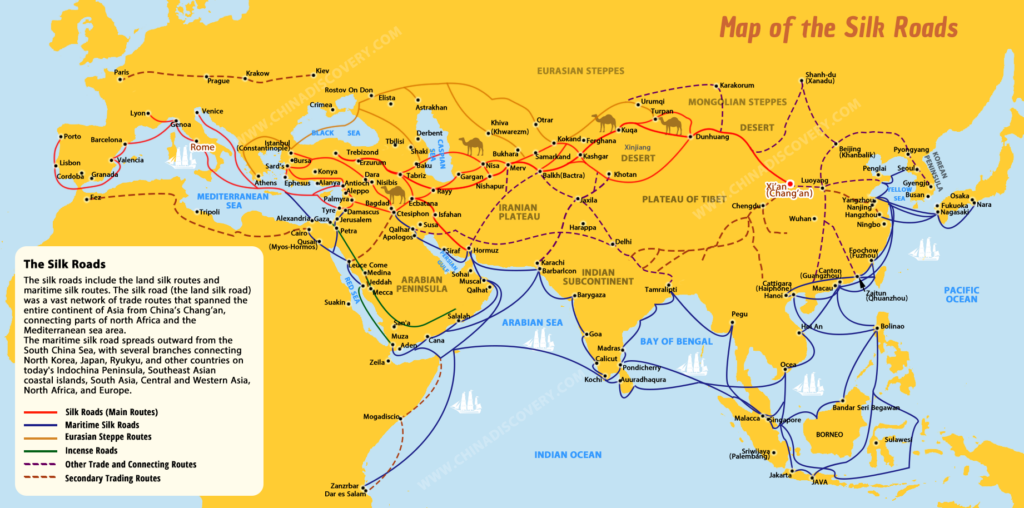

b. International rebalancing: the “BMB” axis along a multicentric silk road

The first Chinese character of the word for China is “zhōng” (中), which means “center.” This lexical artifact corroborates that the dominant logic and formative paradigm of Chinese leaders for several millennia have been to regard their empire as the core, implying that other states merely constitute the periphery. To succeed in the global arena, though, China needs to fully leverage the power of transnational win-win partnerships.

The key catalyst for achieving this transformative purpose is to build what I call a “multicentric new silk road” in a realigning world. In this context, the current challenges are a blessing in disguise for China, since it provides the country with the stimulus to channel its main efforts to countries with great growth potential that currently are not subject to the dictates of the Collective West or at least can be wooed away from it.

A Chinese proverb says that, if you want to get rich, you should build a road first. China’s paramount leader, Xi Jinping, seems to have heeded this advice when he spearheaded the development of a “New Silk Road” (also called the “Belt and Road” initiative) in 2013. The essence of this project was to finance huge infrastructure projects in more than 150 countries around the globe to link the Central Kingdom with a wide variety of international trading partners. In contrast to many Western countries which are keen to give moral sermons, China, to put it succinctly, gave airports, not lectures, to host countries. While the geostrategic program clearly helped to improve the growth prospects of many countries that obtained funding from China, it often resulted in bad debt and the need for China to restructure loans.

Going ahead, China needs to learn how to function as a peace-inducing stabilizer, powerful integrator and inspiring orchestrator in a realigning world. This implies that its movers and shakers need to play the leading part not only in binary relations, but also in vitally important multilateral networks, including the envisaged polycentric new silk road.

Given China’s long history of focusing on internal affairs rather than expanding internationally (apart from the earlier expansions of its empire), it has not yet fully developed the cross-cultural mindset and multilateral skills needed for achieving transnational excellency.

As regards the boundary-spanning mindset, the Central Kingdom should move away from the “Chinatown” paradigm of isolated and self-contained ethnic communities abroad and strive for full immersion in foreign countries without giving up its identity. Moreover, a good national role model for the skills needed to serve as stabilizer, integrator and orchestrator in transnational webs is Germany which, at least in the past, managed to play a leading political role and prosper economically at the center of the European Union (EU).

In contrast to Germany, though, which has made the error of sacrificing national sovereignty and giving away huge sums of money to self-centered “partners” without commensurate returns, China should act on the basis of national autonomy in decision making and invest only in profitable projects. Importantly, it needs to continue to respect the sovereignty of its international partners instead of trying to outsmart them through multilateral brinkmanship.

Applied to the New Silk Road, the new polycentric development paradigm means, for example, that China, when financing overseas infrastructure projects, should increasingly take other lenders on board in a collegial fashion—especially actors that belong to the rapidly expanding BRICS alliance—instead of acting alone and assuming all risks.

In doing so, China should strive for great transparency and authenticity with respect to its objectives and methodology, clearly separating politics from business. It also need to adopt a more targeted approach with clear strategic priorities instead of a shotgun-type modus operandi. For example, China should consider focusing more on directly investing in promising foreign countries on the basis of sound risk assessments rather than mainly relying on lending funds, which in the past tended to be channeled especially to high-risk countries.

The cornerstone of the post-modern polycentric silk road should be a triple political, economic, military, cultural, spiritual and moral alliance inside a Pan-Asian growth pyramid[5] or Pan-Asian growth triangle[6] along a new powerful strategic axis spanning China, Russia and Germany. I call this new strategic construct the “BMB axis” based on the first letters of the participating members’ capital cities (Beijing, Moscow and Berlin).

The BMB trinity should act as a firewall against U.S. hegemony and serve as a seedbed for thousand sovereign flowers to blossom. In this context, it is important for Germany to leave the EU and NATO as soon as possible. Those are parasitical organizations that undermine Germany’s national sovereignty and suck its strength. Instead, Germany should pivot decisively to the East,[7] which experiences a veritable renaissance in a realigning world. Unlike the EU and NATO, the key concept of the new triple alliance should be the equal rights of all partners who preserve their national sovereignty and concomitant right of self-determination without foreign interference.

It is noteworthy that the current anti-China headwind is a gift in disguise for the PRC, showing that the hostile policies of the Collective West can yield unintended consequences. More specifically, the Central Kingdom should exploit the trend of Western countries trying to decouple themselves from China by focusing even more intensively on building alliances in the Global South with states that have become tired of the West’s neo-colonialist domination. Stressing traditional values, including a clear counter-stance against neo-liberal decadence, should be a cornerstone of China’s new charm offensive, which needs to pair financial and technological means with instruments from arsenal of soft power, or better, silky power and silky might.

Apart from the Global South, China should also try harder to integrate nations that are still allied to the U.S. into the new multicentric silk road, especially if inside these countries there are influential groups pushing for a separation from the so-called “leader of the free world” as part of a sweeping political and cultural counter-revolution. Germany has already been mentioned in the context of the BMB axis as a likely candidate in this regard. In addition, several countries in Eastern Europe and even shaky fellows such as France, Italy and the UK in the West and Japan in the East would be ideal targets for China to woo. After the comprehensive break-up of the EU that I predict to occur in the not-too-distant future, the former constrained member states, too, could become more entrenched partners of the “holy BMB alliance” of the good and willing. Interestingly, after the United States’s trade wars against various countries, it will eventually need to rebuild ties with them, whereas China will already have strong bonds to the affected players.

In addition, China needs to build and maintain at least bridgeheads in other key Western countries, which can be activated at a later stage when the climate becomes more Sino-friendly. This effort should include the fostering of strong relations with gifted elites abroad, which may not yet be in power, but have strong prospects to constitute the national leadership group in the future. As regards Taiwan, China could offer a peaceful reunification project, embracing a “one country, three systems” paradigm.

By adopting a less hostile stance internationally, China can reap a high peace dividend. It may be able to reduce military spending and channel the savings to its strategic development projects, helping it to accelerate the rate of technological progress, the sole driver of sustained increases in income per worker in the long-run steady state, in a situation where its labor base is shrinking and becoming more expensive and capital efficiency is declining.

In general, the key to success in politics at home and abroad is foresight, prudence and openness paired with constancy of overarching purpose and strategic intent, as well as sustained flexibility with respect to the individual tactics used in changing circumstances. Therefore, China should not follow the pendulum-like shifts that are characteristic of the policy pattern seen in many countries in the Collective West, but persistently focus on those fundamentals that really matter.

In particular, China once again should focus more on developmental economics than on ostentatiously drawing attention to security matters (including public musings about possible schemes to retake Taiwan by force). In many cases, it should move inch-by-inch to its target in an unspectacular and therefore largely overlooked manner, achieving exponential transformative gains as a result.

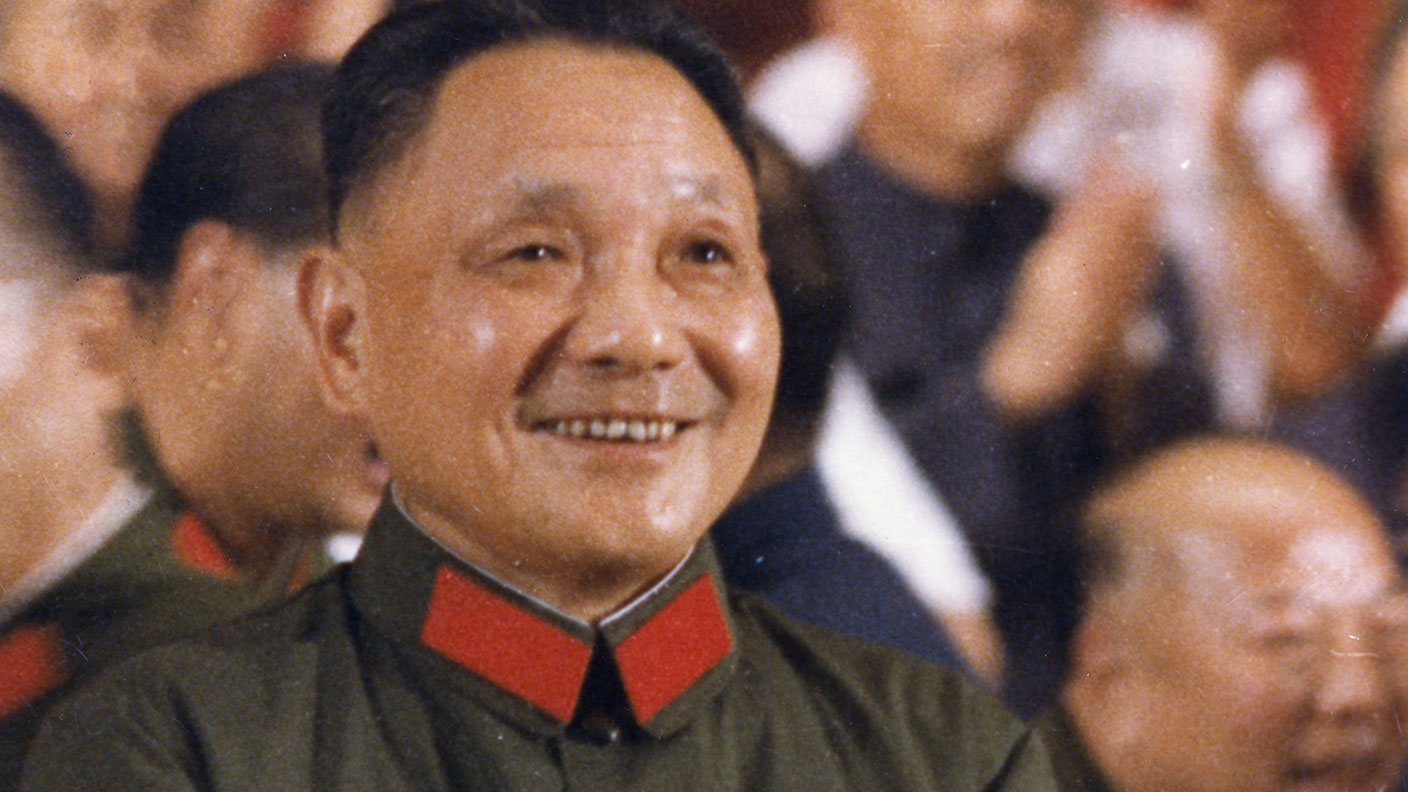

Put in a nutshell, the Chinese president should choose Otto von Bismarck (the former chancellor and architect of the Second German Empire), Lee Kuan Yew (the founder of modern Singapore) and Deng Xiaoping (the mastermind of China’s Reform and Opening policy) as role models who pursued a far-sighted and cautious realpolitik, rather than Wilhelm II, the last German emperor, who destroyed Bismarck’s smart web of alliances, took excessive risks and eventually lost his empire.

To conclude, when thinking strategically about national development, you, as China’s paramount leader-in-thought, need to focus on identifying and pulling key levers in a systemic, counter-cyclical and balanced fashion on a realigning gameboard with enabling and inhibiting forces at work. Conducive domestic policies will help China to build internal strength. At the same time, smart foreign policies will play a pivotal role for its survival and success, since the global arena constitutes the ecosystem in which China can either blossom, stall or suffocate.

If the Chinese president builds a polycentric new silk road in the rapidly changing world, with the BMB trinity as a key driving force, and focuses on the virtues that led to China’s spectacular rise after 1978—most importantly, a low-key concentration on economics instead of ostentatious gunboat diplomacy (in German: Kanonenbootpolitik)—it will be able to thrive even in the current crisis and achieve long-term, sustainable peace and prosperity thereafter based on silky power and might.

*This is a revised version of an article first published on RT World News on 25 January 2025.

Peter Hoskins, “Trump vows tariffs on Mexico, Canada and China on day one,” BBC News, November 26, 2024, Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cvg7y52n411o ↑

N. Gregory Mankiw, Macroeconomics (9th ed.) (New York: Worth Publishers, 2016), 217. ↑

Mankiw, Macroeconomics, 237. ↑

Kai-Alexander Schlevogt, The Art of Chinese Management: Theory, Evidence, and Applications (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002). ↑

Kai-Alexander Schlevogt, “Building the pan-Asian growth pyramid,” The Jordan Times, April 18, 2007. ↑

Kai-Alexander Schlevogt, “Discovering the new geopolitical and geoeconomic heartland of the world: The immense potential of the Pan-Asian growth triangle.” In Kai-Alexander Schlevogt, Brave New Saw Wave World: Emerging and Submerging Asia in the Global Environment (London: Pearson/FT Press, 2011), 87-91. ↑

Kai-Alexander Schlevogt, “Germany’s future lies in the East,’ The Jordan Times, March 2, 2008. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Prof. Dr. Kai-Alexander Schlevogt is a globally recognized expert in strategic leadership and economic policy.

He has served as Full University Professor at the Graduate School of Management (GSOM), St. Petersburg State University (Russia), where he held the University-Endowed Chair in Strategic Leadership.

He also held professorships at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and Peking University.

Kai-Alexander can be reached at schlevogt@schlevogt.com.

His website is www.schlevogt.com

Excellent article. Here is an interesting comparison of Taiwan’s economy and China’s economy:

https://www.managementstudyguide.com/china-vs-taiwan-an-economic-comparison.htm