President Luis Arce came to power in late 2020 with a leftist discourse and as the chosen successor to Evo Morales.

Five years later, he ends his term without the possibility of running for re-election (he stepped down after polling at just 1%) and with hundreds of political prisoners—all of them, paradoxically, from the same Indigenous and working-class sectors that had voted for him.

The political proscription of opponents, economic crisis, and social chaos make up the true reality of today’s Bolivia.

On June 6, Bolivia’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) approved ten presidential tickets that registered for the upcoming general elections on August 17. Evo Morales was not included nor was anyone from his National Action Party (PAN-BOL).

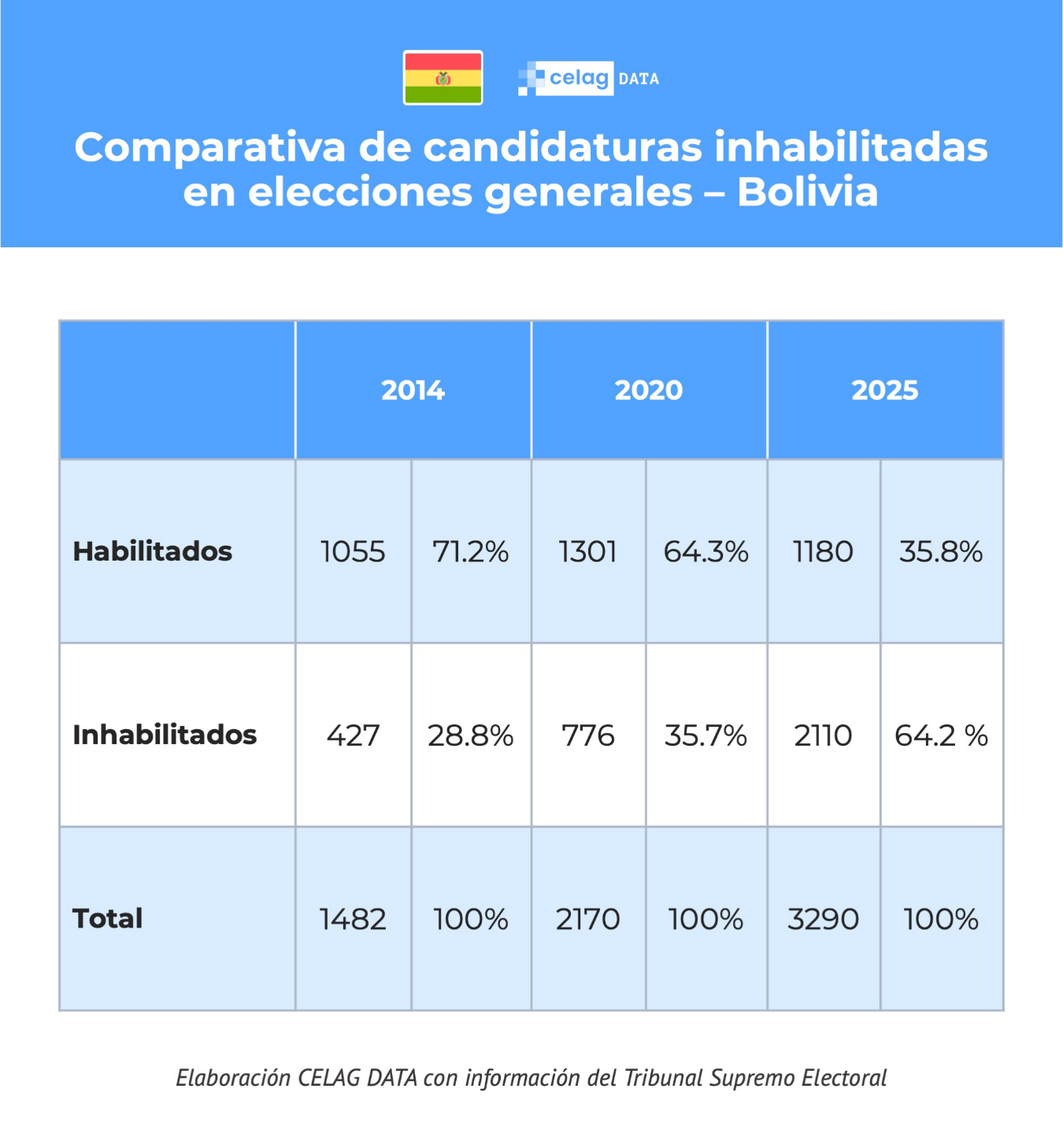

Although political parties are allowed to replace their candidates until July 3, the fact remains that 64.2% of all candidacies submitted by political parties were disqualified for failing to meet various requirements (see chart).

Gabriela Montaño, former Minister of Health under Morales and former President of the Senate, described the situation for CovertAction Magazine: “It is possible that any political party aligned with the popular bloc will face disqualification. Over 200 peasant leaders have been imprisoned, accused of terrorism. The attempt to ban them, to shut the door of democracy on the popular sectors, forces them to mobilize and take action outside the electoral process in order to try to solve the country’s problems. The government has already announced it will repress these mobilizations and imprison their leaders. There is a clear intent by both the right and Arce’s government to exclude vast sectors of the population from democratic electoral life. This carries serious risks: What cannot be resolved through electoral means will find other paths—social mobilization, which runs the risk of being brutally repressed.”

Arce’s government accused the former president of “terrorism” and other crimes for allegedly ordering road blockades. A video showing the leader urging one of his followers to block roads was enough for the prosecutor’s office to open a criminal investigation.

The persecution went so far as to include the arrest of Ponciano Santos, a leader linked to Evo Morales, who was inside an ambulance at the time.

Bolivia is facing a fragmented polarization: on one side, a right-wing camp with seven candidates whose political project excludes the majority of the population, leaving out the various Indigenous and peasant groups that make up the country’s unique Plurinational State.

The right-wing opposition bloc is led by former President Jorge Quiroga (Libre), businessman Samuel Doria Medina (Unidad), and the mayor of Cochabamba, Manfred Reyes Villa (Autonomy for Bolivia). The first two are considered the most likely to reach the runoff.

“The right has failed to build a national political project and has reduced itself to being a substitute for the popular project, through expressions of hatred and intolerance toward popular sectors—there is no national vision,” says political scientist Jorge Richter. “These presidential tickets reflect the most urbanized sectors of our country; there is no diversity, no ‘otherness’ represented in these formulas. For them, it is a time of technological innovation, not of sociopolitical insight—which is truly what matters, even more than the economy,” Richter adds.

On the other side, the left is also divided, with one of its most important leaders barred from running as a candidate. The argument is that Evo Morales has already served as president and the Constitution does not allow him to run for another term. One political fact reinforces this theory: Back in 2016, Evo called for a referendum to allow him to seek a fourth term—and lost, 51% to 49%.

“At that time, Evo Morales was aiming for a new electoral term—his fourth consecutive one. It was a rupture of the institutional order, a coup d’état, that brought his presidency to an end just two months before his term was due to expire. From that moment on, the MAS (Movement for Socialism) entered a kind of internal conflict—at first quiet and subdued. But by 2020, tensions escalated into a confrontation between Evo Morales, who was trying to retake control of the party and secure the presidential candidacy, and current president Luis Arce, who envisioned himself as Evo’s successor—perhaps even his natural one. In the end, neither succeeded: Evo was not able to run, and Arce, after taking over the party, was not able to become the candidate of the social movements. This has led to a split within the left. For the first time, socialism will head into an election divided,” explains Richter.

As further evidence of the breakdown between Morales and Arce, the current president selected Eduardo del Castillo (whose approval rating hovers around 1%) as his candidate for the historic Movement for Socialism (MAS). Del Castillo is the minister responsible for internal security and the police—the same police who carried out an operation that nearly cost Evo Morales his life. “Del Castillo took a political stance of criminalizing social leaders and movements,” says Gabriela Montaño. Del Castillo has also faced internal criticism from MAS grassroots sectors, who see him as more loyal to state power than to the party’s founding principles.

For political scientist Jorge Richter, “Bolivia has experienced a cleavage since December 2005, when MAS secured electoral victory, initiating a ‘process of change’ that can be interpreted socio-politically to understand Evo Morales’s long hold on power. However, from the perspective of liberal institutionalism embedded in our new Constitution, it can also be seen as an obsessive fixation on power with authoritarian tendencies to avoid relinquishing control. Both interpretations are valid. But by 2019, this process of change began to run out of steam and was not renewed.”

The challenge for these elections is to build a national project that includes the different national groups within the Bolivian state. As Richter states, “societies organize their coexistence, and it must be based on equality, only then can economic development models be discussed. The right has no national project. A balance of powers is essential, which is also a balance of representation. And that means organizing and harmonizing coexistence among the various sectors inhabiting the same territory.”

The grave problem is that this political process stems from political proscription. From a tutelary democracy, it is almost impossible for an inclusive national project to emerge.

One possible solution would be for all popular sectors to unite behind candidate Andrónico Rodríguez, who has a natural connection with Evo Morales because he comes from the same popular movement in the country: the Cochabamba Tropics region and the coca-growing areas. Gabriela Montaño believes that “not only is a meeting between Evo and Andrónico possible, it is desirable. It is the most logical option if we want to avoid a solution through disaster.”

Richter is categorical: “In Bolivia, politics is made with the Plurinational State, with diversity, sectors that can no longer be left on the margins as has historically been their fate.”

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Hernán Viudes is an independent journalist and a graduate from The Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires. He lives in Argentina and enjoys music, culture and football.

Hernán can be reached at hernanviudes@gmail.com.