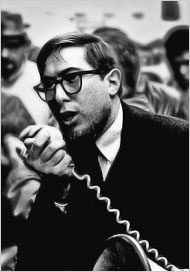

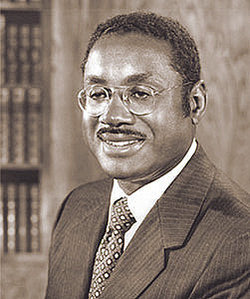

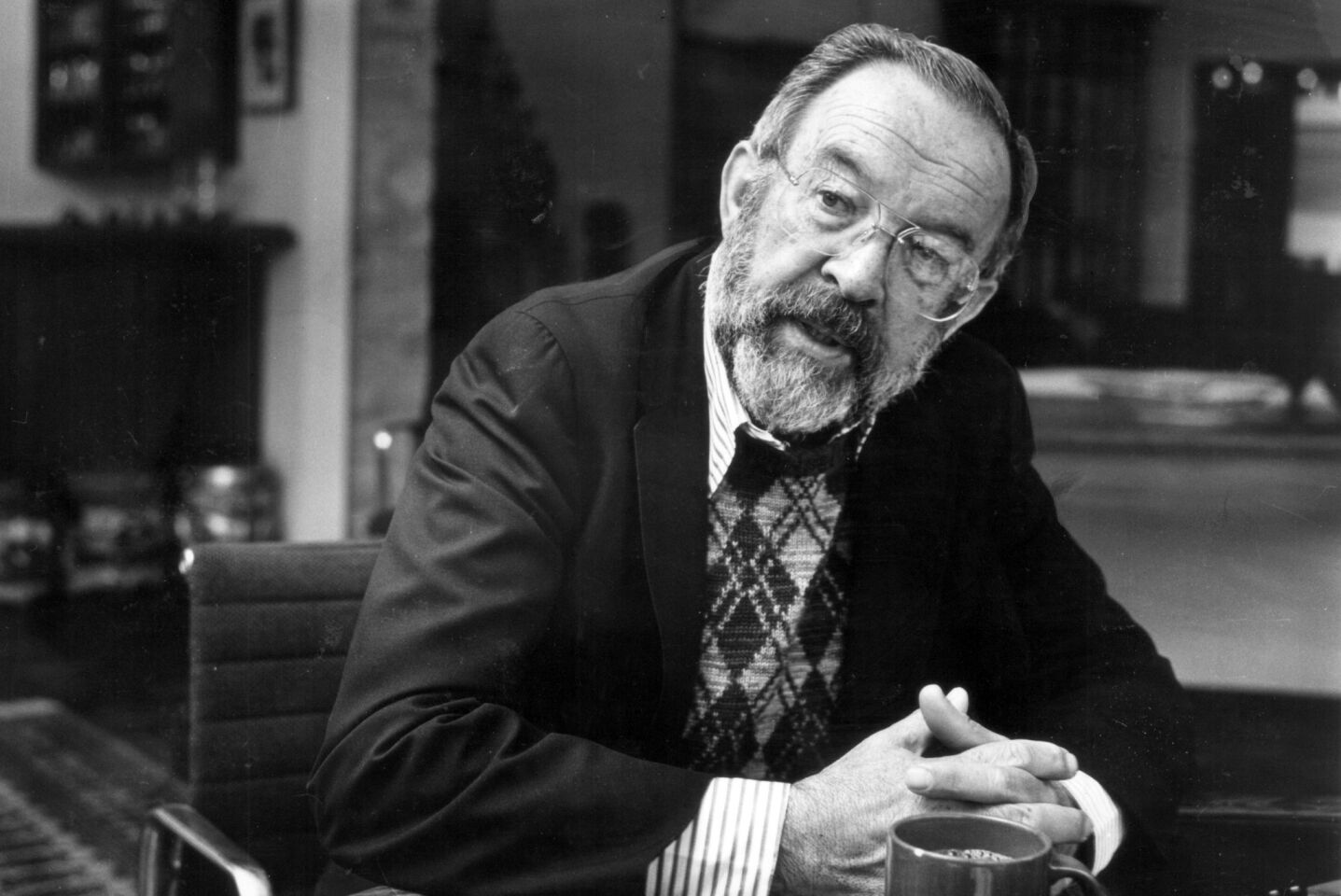

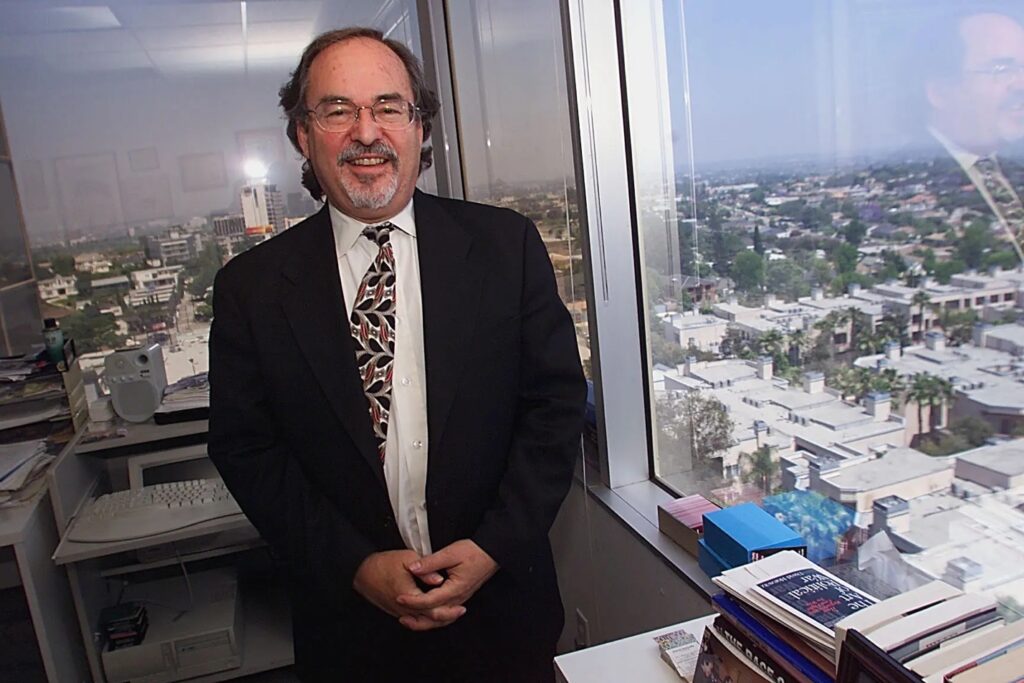

On April 29, American conservative firebrand David Horowitz died at age 86 after a prolonged battle with cancer.

When the news broke, tributes came pouring in on right-wing social media, with everyone from Dutch Freedom Party leader Geert Wilders to Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk, a young Horowitz protégé, eulogizing the radical-turned-reactionary.

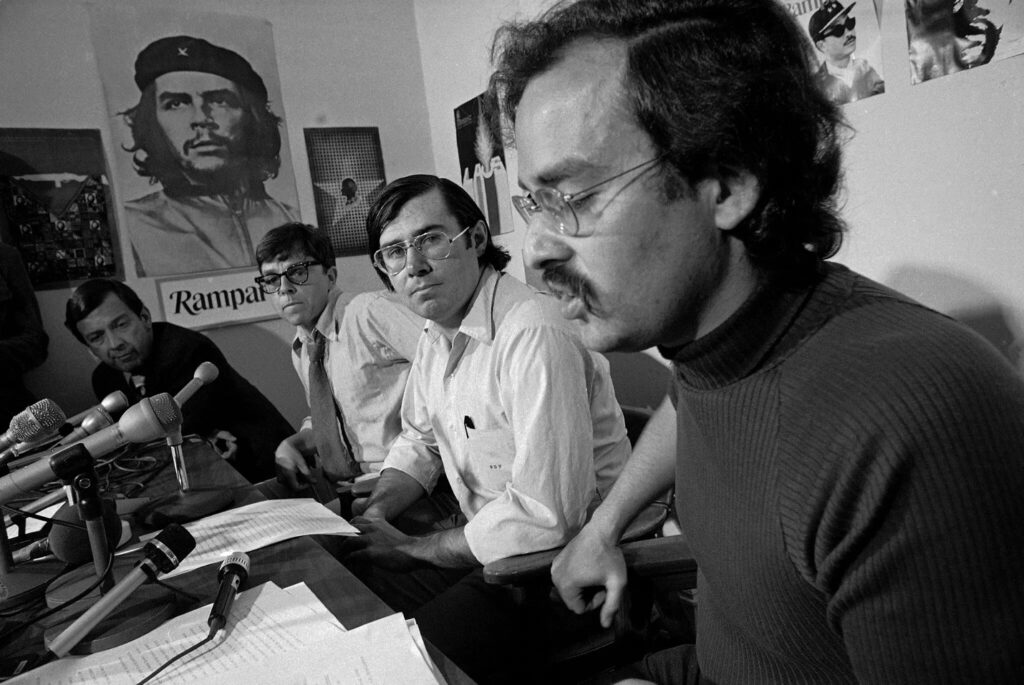

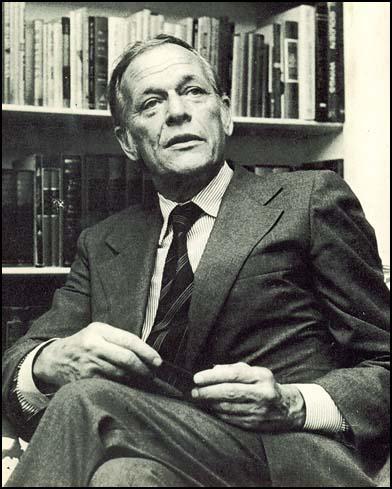

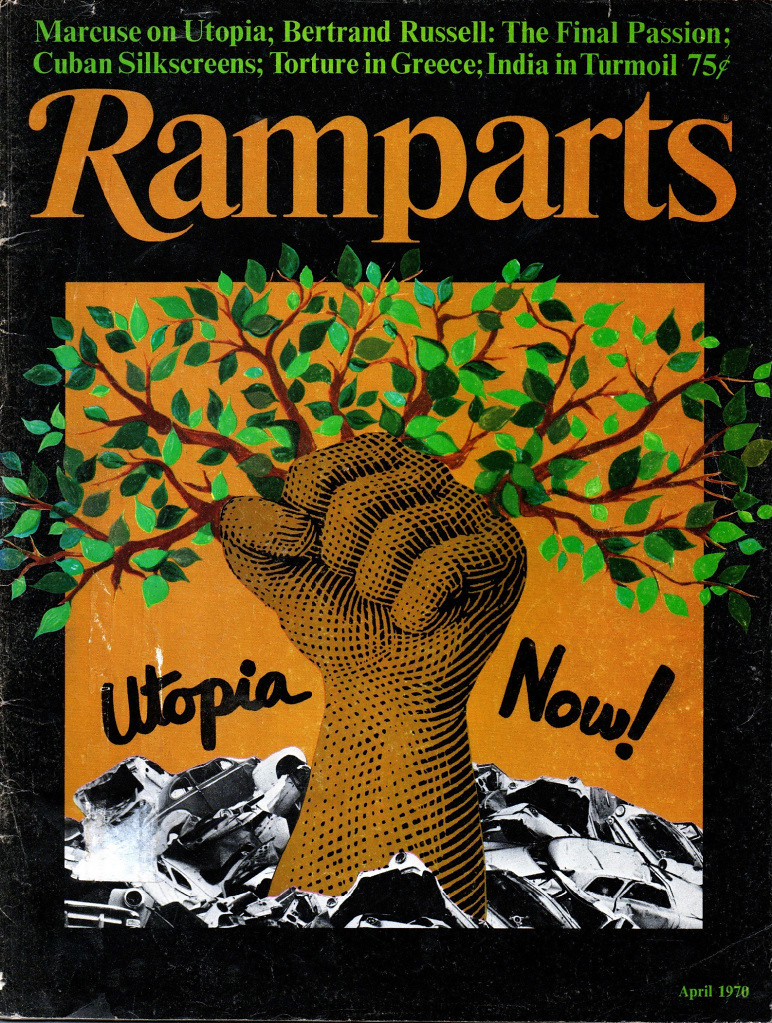

Formerly a prominent member of the New Left and a one-time editor of the legendary Ramparts magazine, Horowitz converted to neo-conservatism during the Reagan era and became an outspoken critic of the left, penning countless books denouncing the progressive causes he championed in his youth.

In the last phase of his life, Horowitz embraced the right-wing populism of Donald Trump, alienating even many of his fellow ex-radical neo-con converts. Far from being an anomaly, however, his circuitous journey from one end of the political spectrum to the other is not as unlikely as it may seem.

David Joel Horowitz was born on January 10, 1939, to Jewish parents in the Forest Hills section of Queens, New York. His grandparents on both sides of the family had fled the Russian Empire during a period of widespread anti-Semitic pogroms and immigrated to the United States.

His mother and father, Philip and Blanche Horowitz, were both New York City high school teachers and long-time members of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). A self-described “red-diaper baby,” Horowitz’s childhood in the cooperative community of Sunnyside Gardens was immersed in radical politics as soon as he could crawl.

By the age of ten, he had attended his first May Day march and, by his teenage years, was contributing to the youth page of the Daily Worker, the CPUSA’s newspaper. He also accompanied his parents to protests against the prosecution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the American couple executed in 1953 for committing espionage by passing nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union.

One year before the Rosenbergs were given the electric chair, Phil Horowitz was fired by the New York City Board of Education for refusing to answer questions about his membership in the Communist Party.

After 21 years on the job, the elder Horowitz was one of dozens of teachers in the five boroughs dismissed under the Feinberg Law, which allowed for the termination of educators belonging to “subversive organizations.”

At the height of the Red Scare, hundreds more resigned to avoid interrogation over such ties until the law was repealed in 1967 for violating the First Amendment. Despite the eventual backlash against McCarthyism, David’s father never got his job back as an English instructor and it had a profound impact on the family.

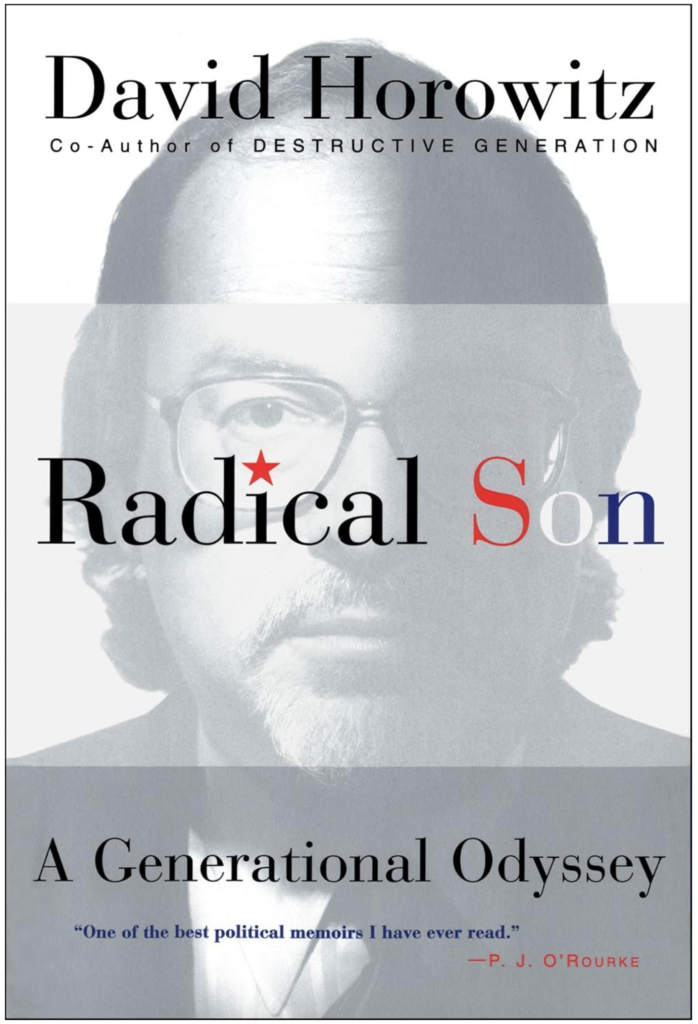

According to Horowitz’s 1997 autobiography Radical Son: A Generational Odyssey, Phil and Blanche indoctrinated young David and his sister Ruth into Marxist ideology during their upbringing in the socialist enclave of Sunnyside. As a young boy growing up in Queens, Horowitz claimed he was forbidden to watch Hollywood movies and had to conceal a love of baseball from his communist father who guilt-tripped him for enjoying America’s national pastime.

However, his sister Ruth maintains otherwise, painting a very different picture of their unconventional adolescence. According to Ruth, she and her brother were permitted to watch any films they wished[1] and, when they were shown Soviet cinema (such as Sergei Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky and Battleship Potemkin), it was to imbue them with a sense of cultural diplomacy.

Phil and Blanche remained loyal to the CPUSA until 1956 when the shattering news of Nikita Khrushchev’s “secret speech” reached stateside in the pages of The New York Times and threw the party into crisis. Initially leaked to the West by the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad, the Soviet premier denounced the purges of the Stalin era and the “cult of personality” under his predecessor’s leadership.

Up to that moment, the international communist movement had been divided between parties aligned with the Comintern and the Trotskyist Fourth International, with CPUSA firmly in the Stalinist camp. Even though Khrushchev’s denunciation contained various demonstrable falsehoods—such as the claim that Stalin, who made his revolutionary name as a prolific bank robber, was terrified as the Nazis were advancing toward Moscow during World War II—it was enough to cause a sharp decline in CPUSA membership. It also reinvigorated the Trotskyist movement whose demonization of Stalin was seemingly validated by Khrushchev’s report.

From that moment on, Horowitz began to forge his own path politically by shunning the orthodox Marxism of his parents, much like many of his generation who would comprise the New Left.

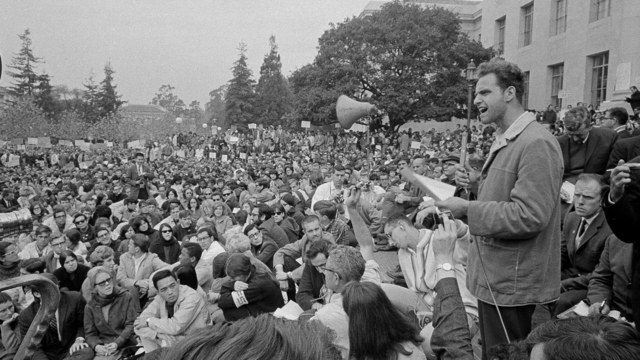

After graduating from Columbia University in 1959 and marrying his first wife Elissa, Horowitz journeyed out to the West Coast to matriculate at the University of California, Berkeley. While pursuing a master’s degree in literature at Cal, Horowitz co-founded the first quarterly journal of the burgeoning campus-based left, Root and Branch, with his future Ramparts colleagues Robert Scheer, Maurice Zeitlin and Sol Stern.

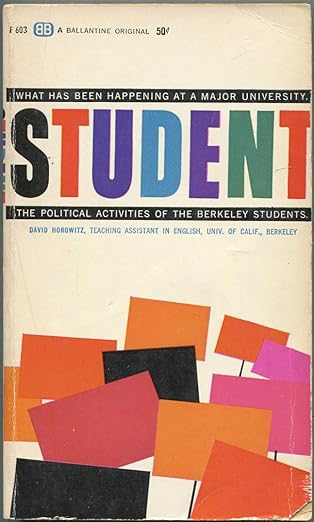

The Queens-born English graduate also helped organize one of the earliest campus rallies against American involvement in the Vietnam War in 1962. That same year, he published his first book, Student, which recounted the protests at UC Berkeley, which was becoming a hub of left-wing activism and the anti-war movement. One of the eventual leaders of the Free Speech Movement, Mario Savio, would later tell Horowitz that Student had inspired him to transfer from Queens College to Berkeley.

By the time Savio delivered his iconic “Bodies Upon the Gears” speech on the steps of Sproul Hall, Horowitz had already gone off to Europe with his wife and children in tow. While living in the outskirts of Uppsala, Sweden, he authored The Free World Colossus: A Critique of American Foreign Policy in the Cold War, which gave an analysis of Western imperialism from a New Left perspective.

Horowitz was careful to denounce the Soviet intervention in Hungary, but he criticized the dominant narrative that expansionism by the USSR was the basis for the Cold War, the cause of which he laid at the feet of American empire-building. Free World Colossus became a widely read text among 1960s radicals and was even referenced in E. L. Doctorow’s classic novel The Book of Daniel, a fictionalized dramatization of the trial and execution of the Rosenbergs that the teenage Horowitz had picketed with his family. The up-and-coming writer then relocated to London where he became a pupil of two European intellectual titans of the mid-20th century Western left.

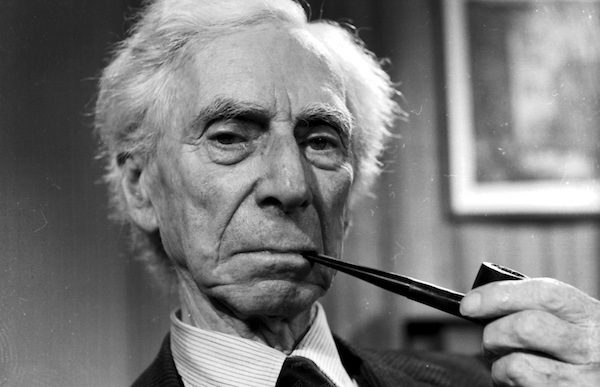

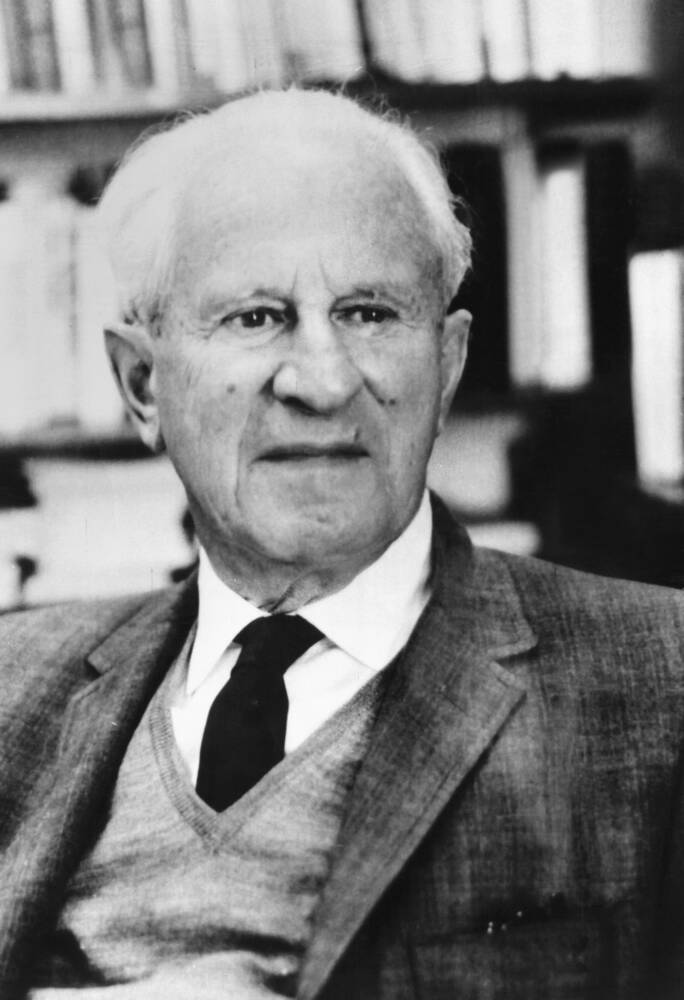

While residing in the British capital, Horowitz came under the wing of Nobel Prize-winning philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell when he was offered a job at the latter’s Peace Foundation. Established in 1963, Russell’s organization famously convened a tribunal on American war crimes in Vietnam which brought together a committee of notable individuals, including the French intellectual power couple Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Yugoslav partisan and historian Vladimir Dedijer, and American novelist and civil rights activist James Baldwin.

The “people’s tribunal” also featured Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Chairman Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture) who subsequently joined forces with the Black Panther Party (BPP), an organization with which Horowitz eventually forged a relationship as well. Under Russell’s patronage, Horowitz helped coordinate the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign which led major anti-war demonstrations in London throughout the decade.

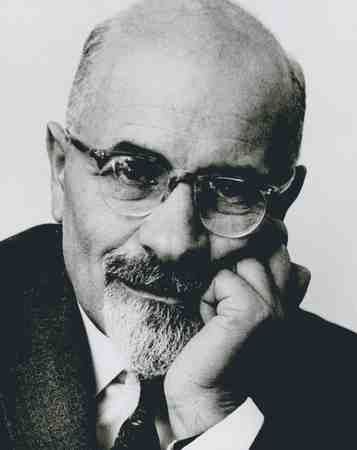

Another member of the International Russell Tribunal was renowned Polish-British Marxist and Leon Trotsky biographer Isaac Deutscher, who in the last years of his life became a mentor to Horowitz. Horowitz dedicated his 1969 book Empire and Revolution to the Kraków-born historian, a work clearly inspired by his politics. Although he still identified as a Marxist, Horowitz was already rebelling against his forebears by participating in the New Left, with its British wave especially bearing the influence of Trotskyism thanks to Deutscher’s three-volume biography of the Russian revolutionary.

Castigating Moscow’s “Stalinist bureaucracy,” Horowitz sought to salvage Marxism from what he considered to be its deformed Soviet manifestation, while still laying the fault of the Cold War on U.S. imperialism. Like Deutscher and many on the New Left, he was deeply disillusioned with the perceived authoritarianism of the Soviet model upheld by his mother and father, but still advocated revolutionary socialism.

In 1968, Horowitz reconnected with his one-time Root and Branch collaborator Robert Scheer, who had since become an editor at Ramparts. Scheer offered him a writing and editing position which he accepted, and Horowitz returned to the Bay Area—where Ramparts was based—in the throes of the emerging counterculture.

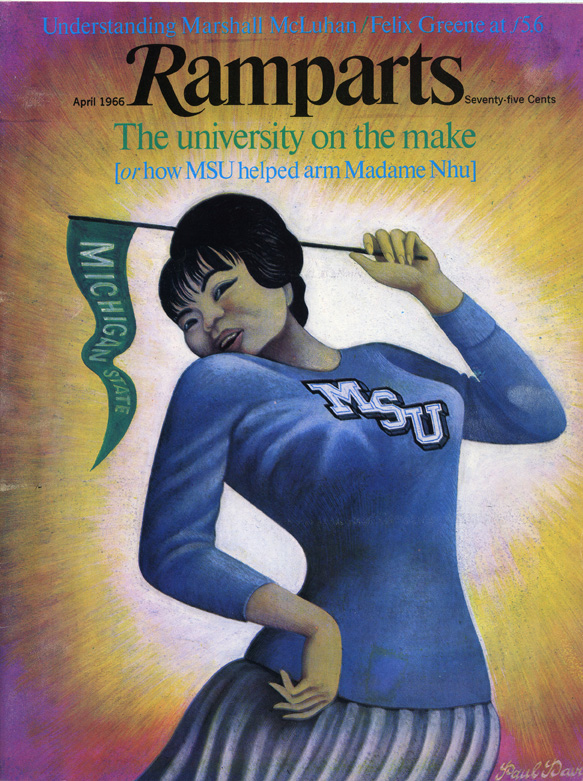

Originally a Catholic literary quarterly, Ramparts underwent a major transformation under the editorship of flamboyant gonzo journalist Warren Hinckle, evolving into a politically oriented radical left publication known for its glossy, illustrated layout and muckraking investigations.

A short list of those who contributed to Ramparts in its heyday include Noam Chomsky, Seymour Hersh, César Chávez, Susan Sontag, Abbie Hoffman, Todd Gitlin, Jerry Rubin, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, I. F. Stone, Regis Debray, Eduardo Galeano, Benjamin Spock, Murray Bookchin, Jean Genet, Howard Zinn, Peter Dale Scott, Alexander Cockburn, Christopher Hitchens and many more. The magazine also published the diaries of Ché Guevara, compiled from the notebooks found in his backpack when he was captured and executed by the U.S.-backed Bolivian Army in 1967.

A year earlier, Ramparts began its association with the Black Panther Party by running essays written by an incarcerated Eldridge Cleaver, which were later assembled into his influential memoir Soul on Ice. Among its editorial staff were journalist Adam Hochschild who later started Mother Jones, as well as music critic Jann Wenner who left to found Rolling Stone magazine, which clearly emulated the cutting-edge stylistic design of Ramparts.

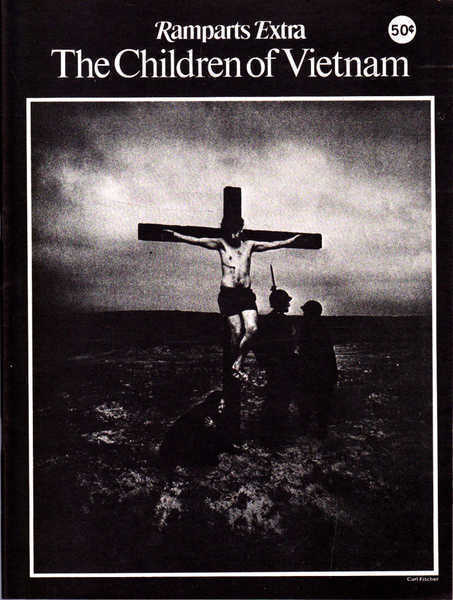

The left-wing monthly was also recognized for its strong opposition to the Vietnam War, frequently challenging U.S. government edicts and satirizing the mainstream press coverage. At its peak, the magazine reached a mass-circulation of 400,000, a feat virtually unheard of for a subversive outlet. Its January 1967 photo essay by William F. Pepper, “The Children of Vietnam,” which captured the horrific effects of napalm and Agent Orange on Vietnamese children, was credited with motivating Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., to finally speak out against America’s bombing campaign in Southeast Asia.

Its most explosive and historically important exposé, written by Sol Stern, came the following month when it revealed that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was covertly funding the National Student Association (NSA) as a conduit for its overseas operations. Through various front foundations, the agency funneled money to the NSA as a cutout for its international activities and the bombshell report led to a major scandal when the story was picked up by The New York Times and other newspapers.

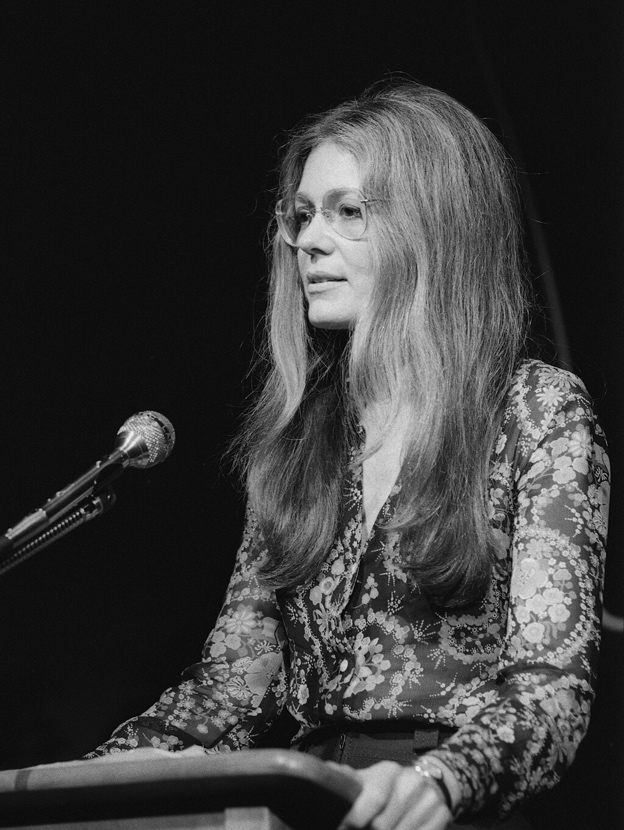

Ramparts also uncovered how the agency created front organizations like the ironically named Independent Research Service to recruit delegations of American students to infiltrate events held in Europe by the Soviet-sponsored World Festival of Youth and Students. The operative in charge of the dummy corporation was none other than future second-wave feminist icon Gloria Steinem, who was a witting participant in the CIA’s scheme. “If I had a choice, I would do it again,” said the activist in a televised interview with Mike Wallace of CBS News.

For his part, Horowitz penned a series of sophisticated articles for Ramparts exploring how American universities were “knitting the sinews of empire” in cultivating close ties to the State Department, the Pentagon, and multinational corporations. Horowitz also highlighted the role of tax-exempt organizations like the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations in facilitating the revolving door between academia and “American imperium.”

The disclosures about the CIA’s ties to the NSA were just the tip of the iceberg and merely one component of a larger ideological soft-power battle behind the scenes. Beginning in 1950, the agency launched a massive propaganda campaign using phony foundations to manipulate various cultural activities, as part of a top-secret project called the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF).

Recipients of the CIA’s largesse included art exhibitions, literary journals (such as Encounter, Der Monat, and Partisan Review), international conferences, book publishers, and various other enterprises through false-front organizations. Hoping to diminish Soviet sympathies among the Western left intelligentsia, the CCF was founded in 1949 by a cabal of anti-communist intellectuals, including Arthur Koestler, Sidney Hook and Irving Kristol.

Its objective was to cultivate the artistic and intellectual milieu of the period into what British historian Frances Stonor Saunders refers to as the “non-communist left” in her book The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (or what the American academic Gabriel Rockhill calls the “compatible left”).

Oddly enough, one of the patrons who attended the inaugural conference of the CCF in West Berlin was David Horowitz’s mentor Bertrand Russell, who in the immediate post-war period was supportive of a hawkish stance against the USSR though ultimately took a strong stand against the Vietnam War.

As soon as the U.S. monopoly on the bomb ended, Russell’s position evolved into a bourgeois pacifist stance, advocating the abolition of all nuclear weapons and co-authoring an anti-nuke manifesto with Albert Einstein. At the peak of the arms race, Russell’s work was also promoted in publications underwritten by the Information Research Department, a shadowy branch of the British Foreign Office that covertly disseminated anti-communist propaganda. An honorary president of the CCF, Russell left the forum in 1956 after the execution of the Rosenbergs, supposedly unaware that its financing had come the entire time from the CIA.

Philosopher Hannah Arendt and several other intellectuals later signed a statement in Partisan Review feigning ignorance about the “secret subsidization by the CIA of literary and intellectual publications and organizations.” When asked for his reaction, the agent who oversaw the CCF, Tom Braden, was quoted by Frances Stonor Saunders as laughing and saying, “of course they knew.”

Despite its own role in the divulgence of the CIA’s cultural front in the Cold War, Ramparts was in many respects a product itself of the “compatible left” that the CCF had strived to develop, as the New Left’s flagship publication. The campus-oriented movement was characterized by a shift from the traditional focus on organized labor and the class struggle toward an emphasis on identity politics and broader social issues, such as civil rights, environmentalism and sexual liberation.

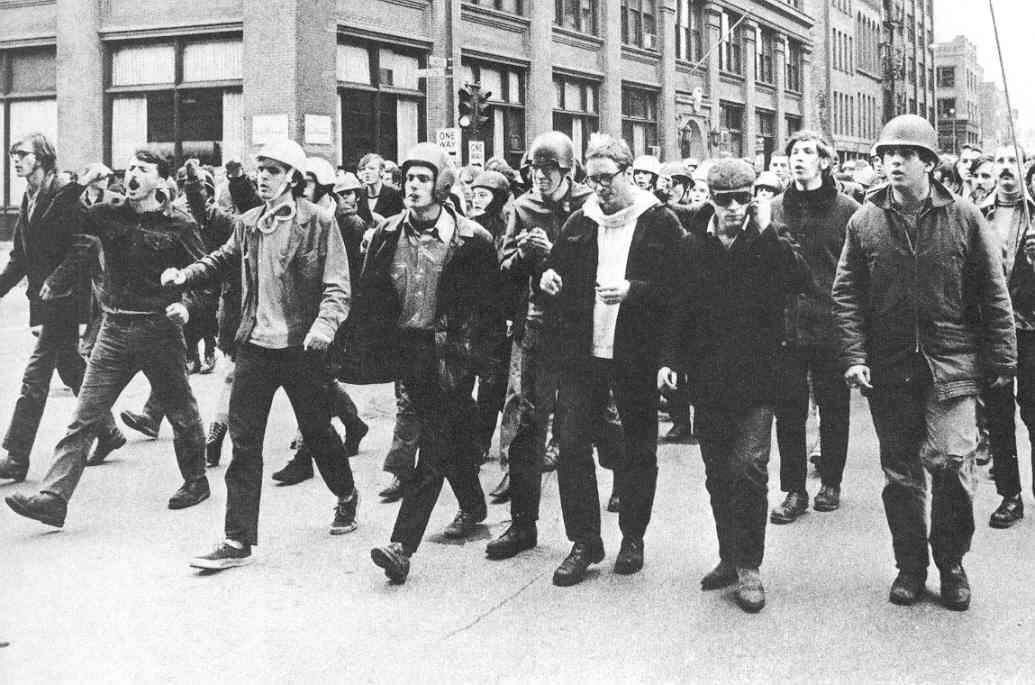

Although the New Left was not a monolith, the 1962 Port Huron Statement written primarily by Tom Hayden of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), decried the “dreams of the older left perverted by Stalinism” and the “sure formulas” and “closed theories” of Marxist-Leninist dogma. The new agents of revolutionary change were students and racial minorities, rather than the working class. Its tactics were spontaneous, leaderless and decentralized, as exemplified by the May 1968 protests in France and the demonstrations against the Democratic National Convention in Chicago that same year.

An interview with the intellectual godfather of the movement, Frankfurt School critical theorist Herbert Marcuse, and his essay “The End of Utopia,” graced the pages of the April 1970 issue of Ramparts as its cover story. The following year, the magazine ran Marcuse’s letter to an imprisoned Angela Davis, who had been one of his students in West Germany at the University of Frankfurt. [During World War II, Marcuse had worked for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the CIA’s war-time predecessor. After the OSS dissolved, he continued working for the U.S. State Department, producing an anti-Soviet data study that served as the basis for his 1958 book Soviet Marxism: A Critical Analysis.]

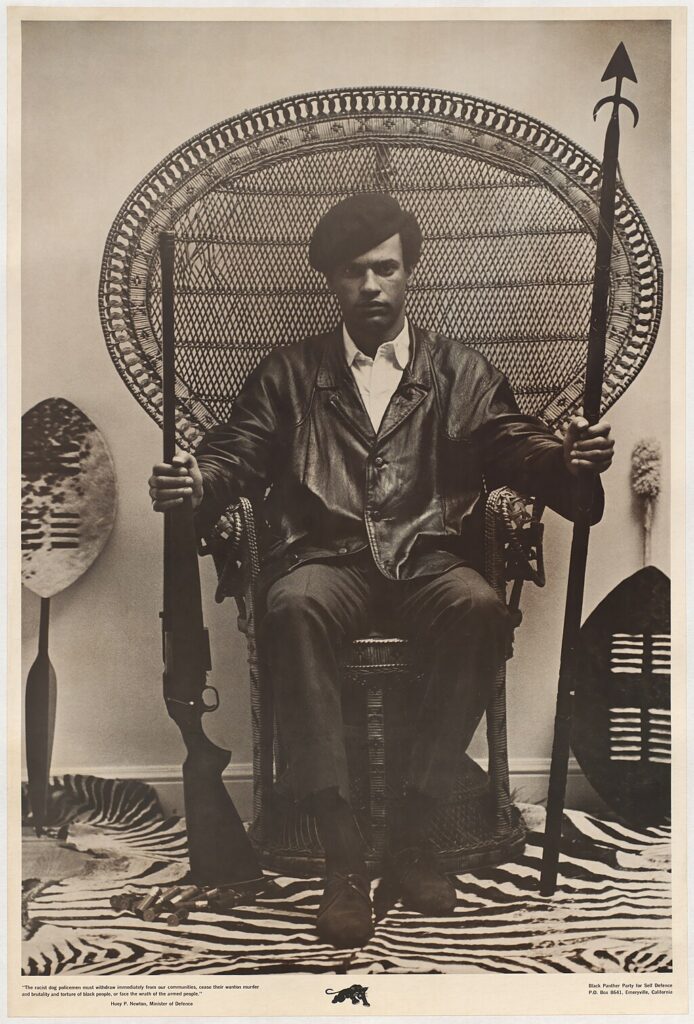

While Davis was influenced by Marcuse, the Black Panther Party collectively drew greater inspiration from the work of anti-colonial writers like Frantz Fanon. David Horowitz had kept the Panthers at arm’s length for the duration of the 1960s due to their overt militancy, but Huey P. Newton’s 1972 pronouncement that the party was “putting down the gun” to “serve the people” through community service drew him closer to the party.

At the time, the Panthers were deteriorating due to suppression and infiltration by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), with the engineered schism between Newton and Eldridge Cleaver dividing the party between East and West Coast factions. Horowitz befriended Newton, who convinced him that the Black revolutionaries were putting militance behind them and directing their resources full-time toward “survival programs” in inner-city neighborhoods like Oakland. The Ramparts editor volunteered to help raise funds to purchase the Oakland Community Learning Center, which contained a school and numerous youth programs, and was one of the BPP’s most successful endeavors in utilizing dual power and mutual aid.

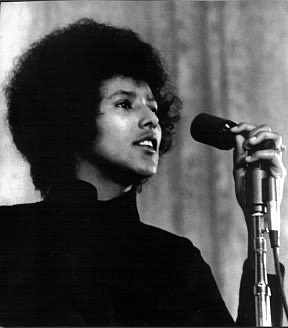

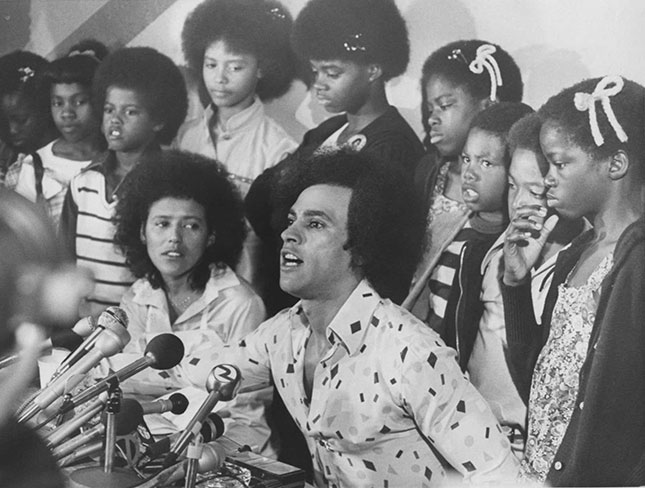

In August 1974, a drug-addled Newton fled to Cuba to avoid prosecution for the alleged murder of a prostitute. Elaine Brown, a high-ranking Panther who had unsuccessfully run for the Oakland City Council, was appointed to chair the party in his absence.

At the time, the Black Power group was in need of someone to keep track of their financial records, and Horowitz suggested a bookkeeper from Ramparts named Betty Van Patter. The party hired her, but a few months later—in December—Van Patter reportedly had a run-in with the new chairwoman after she came across illicit transactions in the party finances and was dismissed when she brought them to Brown’s attention.

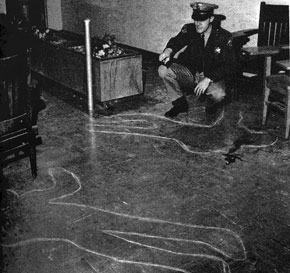

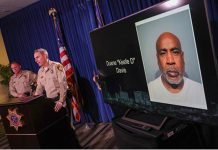

Shortly thereafter, Van Patter vanished, last having been seen at a West Oakland bar and Panther hangout where witnesses saw her leave after an unidentified Black man approached her to deliver a note. A month later, on January 17, 1975, her battered and decomposed body was discovered floating in San Francisco Bay. Needless to say, suspicion quickly fell on Brown and the Panthers.

In his memoir, Horowitz cited this incident as the turning point in his life which began his epiphany and spurred his drift to the right. Van Patter’s killing immediately threw him into a personal and political crisis, as he believed the Panthers were responsible for her homicide and was overcome with guilt for having introduced Betty to the organization.

When no arrests resulted from the police investigation, a private investigator allegedly determined that the Panthers had done the deed, with Horowitz claiming that the party’s supposed “hit squad” carried it out.

While it is possible that the Black liberation group had gotten mixed up in criminality, apparently it never occurred to Horowitz that his friend’s tragic slaying could have resulted from the FBI’s war on the Panthers, which had not ceased even after the revelations about the Bureau’s illegal Counter-Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) a few years prior.

Instigating and exacerbating violence, gang warfare and murder were among the FBI tactics which went well beyond mere disruption. While the operations were officially ended in 1971, harassment and repression of the Black nationalists continued uninterrupted. Surely, if members of the Panthers had been involved in the killing of a white woman, one would assume that law enforcement would be eager to make arrests, unless the culprits were protected by the authorities.

When Elaine Brown announced her short-lived candidacy for the 2008 Green Party presidential nomination, old rumors resurfaced that the first and only woman to chair the Black Panther Party had been a government agent.

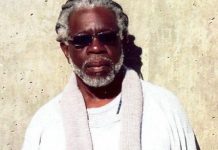

This was based on previous accusations made by Elmer “Geronimo” Pratt, a former member of the Los Angeles faction of the Panthers, who served decades in prison after he was framed by the FBI for the murder of a schoolteacher.

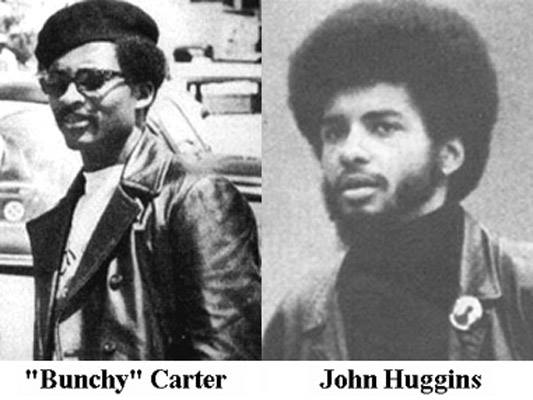

A Vietnam War veteran, Pratt had been recruited into the Panthers by two members of the L.A. chapter, John Huggins and Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter. In January 1969, Huggins and Carter were both shot to death on the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) campus by members of a rival Black nationalist group called the US Organization.

According to acclaimed investigative journalist Dick Russell, US leader Ron “Maulana” Karenga was a known police informant. Two of the suspected gunmen in the UCLA shootout, Claude “Chuchessa” Hubert and Harold “Tuwala” Jones, were said to have escaped to South America with possible government help and were never seen again.

Meanwhile, brothers George and Larry Stiner were each convicted for their roles in the shooting deaths of Huggins and Carter, but conveniently escaped from San Quentin State Prison in 1974. Larry Stiner turned himself into authorities in 1994 (he was paroled in 2015); brother George’s location remains unknown.

The subsequent investigation by the Church Committee into intelligence abuses linked COINTELPRO operations to the escalation of violence between the Panthers and US. As maintained by Geronimo Pratt and others, the gunfight that ended the lives of Carter and Huggins was instigated by Elaine Brown, who was then a rank-and-file member of the party’s Southern California branch and editor of its local paper.

On the UCLA campus, a meeting had been called between the two groups to discuss the new head of the school’s Black Studies program. Allegedly, Brown had an altercation with US member Tuwala Jones, with whom she had previously been intimate, and went screaming to Huggins that she had been assaulted. When Huggins drew his .357 Magnum and confronted Jones, the gun battle ensued.

In the 1996 documentary All Power to the People! The Black Panther Party & Beyond, multiple ex-members accused Brown of being an agent provocateur, with one former Panther named George Edwards going so far as to call her a “highly placed intelligence operative.”

Edwards even claimed that he was told by ex-CIA whistleblower John Stockwell that Newton’s mental health and substance abuse problems were a direct result of the agency’s psychological warfare operations and encouragement of drug use within the Panthers.

In author John L. Potash’s book Drugs As Weapons Against Us, Brown is described as having gotten Newton hooked on cocaine.

Prior to joining the BPP, Brown had been in a relationship with a wealthy music executive and Hollywood screenwriter named Jay Richard Kennedy, who was also the business manager of singer and actor Harry Belafonte. As reported by David J. Garrow in his book The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr.: From “Solo” to Memphis, Kennedy was a former Communist Party member who turned informant for the CIA and FBI.

As he became close to civil rights figures like Belafonte and MLK, Kennedy continued spying for U.S. intelligence, all while hosting a nationwide television panel featuring the leaders of the March on Washington in 1963. In her own autobiography A Taste of Power, Brown credits Kennedy with introducing her to activism and the Panthers (she also admits to firing Betty Van Patter but adamantly denies having anything to do with the unsolved murder).

None of this is mentioned in Horowitz’s account of his time working with Brown, whom he blamed for the death of Van Patter. Not only was COINTELPRO no secret at the time, but neither was the CIA’s equivalent domestic surveillance program targeting the left.

Known as Operation CHAOS, the espionage project was first revealed in a December 1974 article in The New York Times by journalist Seymour Hersh, just a week after Van Patter went missing. Along with the Panthers, Ramparts itself was one of the primary targets of CHAOS and had been in the crosshairs of the CIA since it made the agency’s cloak-and-dagger relationship with the National Student Association public.

In an earlier Ramparts editorial entitled “Terrorism and the Left,” Horowitz had denounced the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), a tiny self-proclaimed “urban guerrilla” organization which gained notoriety for the kidnapping of newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst. (In fear of reprisal, Horowitz did not attach his name to the write-up). As maintained in a report in Argosy magazine by reporter Dick Russell, the SLA was “apparently rooted in the CIA’s Operation CHAOS” and headed by a convicted criminal turned government informant named Donald “Cinque” DeFreeze.

This version of events is supported in Brad Schreiber’s book, Revolution’s End: The Patty Hearst Kidnapping, Mind Control, and the Secret History of Donald DeFreeze and the SLA (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2016).

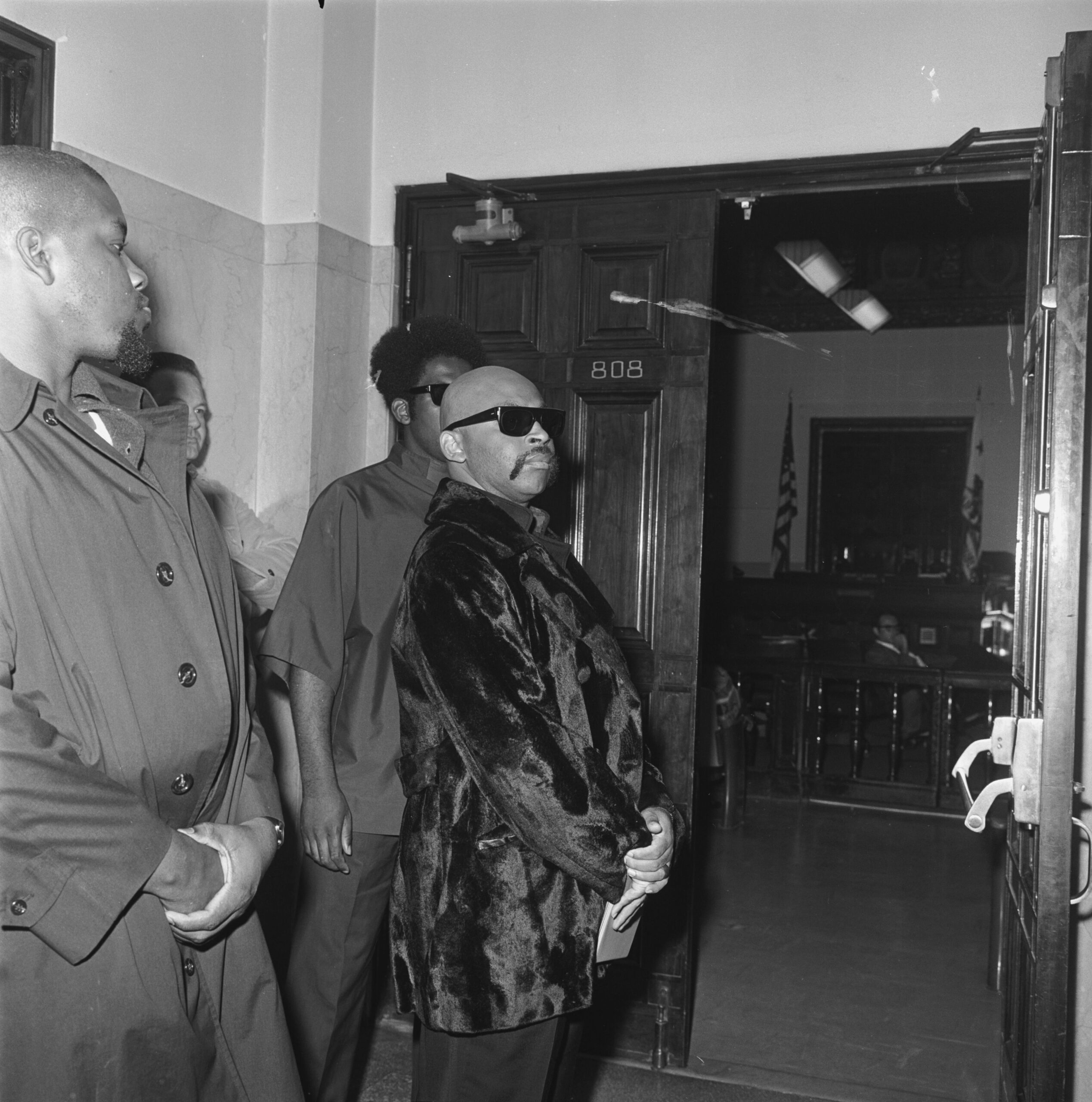

In the late 1960s, DeFreeze had been an informant for the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) and worked with units targeting the Panthers. Also embedded in the police force was a CIA operative and linguist named Colston Westbrook.

In the early 1970s, far left groups had begun to recruit inmates through visitation programs and prison outreach projects, in some cases even facilitating jail breaks for the new “revolutionary vanguard.” One such outfit was Venceremos, a mostly Chicano organization headed by Stanford University professor and Marxist academic H. Bruce Franklin. (The far-left sect had split from the Bay Area Revolutionary Union, which grew into the Revolutionary Communist Party cult led by Bob Avakian.)

The CIA soon penetrated and co-opted these activities when Westbrook was hired to be the “outside coordinator” of an organization of African-American prisoners at Vacaville Prison called the Black Cultural Association (BCA). Concurrently, Westbrook had become a linguistics instructor at UC Berkeley and signed up students to be volunteers for the prisoner support program. Donald DeFreeze soon joined the BCA after he was sent to Vacaville to serve a sentence for armed robbery.

Historically, the Northern California penitentiary was known for utilizing behavior modification programs and DeFreeze is believed to have been subjected to experimental treatments under Westbrook’s supervision.

At Vacaville, the small-time crook and stool pigeon turned the tables and recruited a small clique of Berkeley student radicals as his followers, including two members of Venceremos. After DeFreeze was transferred to Soledad Prison, he easily escaped and took shelter with his band of devotees in the Bay Area where he enlisted them to carry out a string of violent attacks.

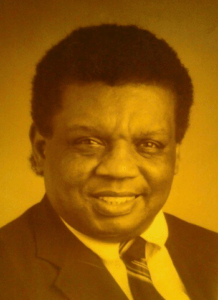

The SLA’s first act of politically motivated terrorism was to assassinate the widely respected Oakland Unified School District Superintendent Marcus Foster, the first Black administrator of a large city school district. In November 1973, the SLA gunned down Foster with cyanide-laced bullets, supposedly over a plan to introduce a student identification card system in the local school district meant to deter vagrancy.

Even though Foster was friendly with the Black Panthers and had been allowing the party’s input on education reforms, the SLA used a slogan attributed to Eldridge Cleaver to justify the murder in its first communiqué, “death to the fascist insect that preys upon the life of the people.” In Ramparts, Horowitz decried the SLA’s misappropriation of the phrase and their likening themselves to the Tupamaros, a Marxist guerrilla group based in Uruguay.

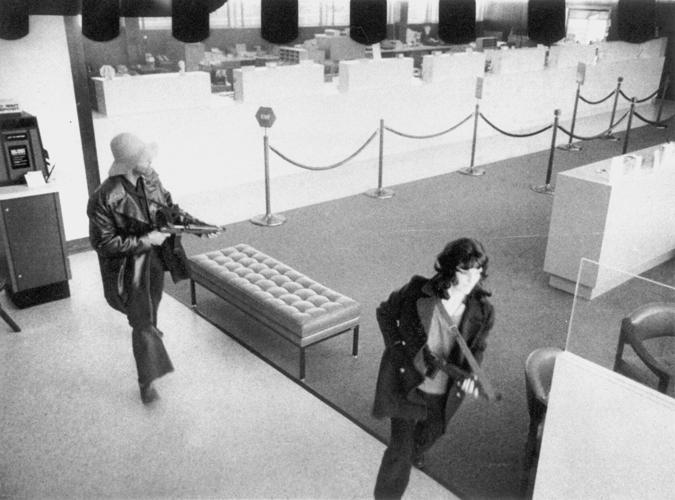

A few months later, the fringe group abducted Patty Hearst, the affluent granddaughter of publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst and a student at UC Berkeley. While in captivity, the 19-year-old supposedly became brainwashed by DeFreeze and willingly participated in the SLA’s bank robberies.

“The Foster killing revolted me,” wrote Horowitz many years later, recalling some of the backlash Ramparts received at the time from other radicals for condemning the SLA. Horowitz claimed Yippie leader Stew Albert and others accused the magazine of giving the go-ahead to the police to hunt down and kill the fugitives.

In May 1974, DeFreeze and the core of the armed group were massacred in a firefight with the LAPD after they fled south to a safe house in Los Angeles, while Hearst was being held separately at a motel in Anaheim. The fugitive inheritress was apprehended a year later and convicted as an accomplice before her sentence was commuted by U.S. President Jimmy Carter.

David Horowitz was repulsed by the New Left’s turn toward violent extremism and confrontational tactics with the SLA and the Weather Underground, a pattern that began following the “Days of Rage” protests in 1969. Unfortunately, he was unwilling or unable to connect the dots between FBI and CIA counterespionage with the increase in ultra-left adventurism, nor to the tragic death of Betty Van Patter.

Instead, Horowitz had a psychological break due to unresolved issues from his upbringing and used Van Patter’s death as an excuse to abandon left-wing politics altogether. His road to Damascus was not instantaneous, however, as he still became a founding sponsor of James Weinstein’s progressive magazine In These Times in 1976.

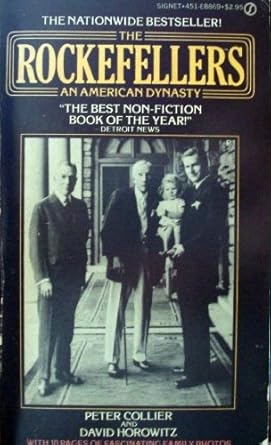

Once Ramparts folded, Horowitz partnered with his co-editor Peter Collier, who also had grown disenchanted with radicalism, to pen a best-selling chronicle of the Rockefeller family—The Rockefellers: An American Dynasty. Fittingly, the book brought him newly found fortune.

By the end of the decade, Horowitz was in complete self-doubt and confusion about his political outlook. Although he claimed to have voted for Jimmy Carter in 1980, by the next election cycle, Horowitz and Collier had both reinvented themselves as Reaganite Republicans, co-writing a 1985 opinion piece in The Washington Post entitled “Lefties for Reagan.”

In 1987, Horowitz organized the “Second Thoughts” Conference in Washington, D.C., where he and several other ex-radicals gathered to repent for their past sins and proclaim their rebirth as conservatives. In the audience was journalist Alexander Cockburn of The Nation, who had begrudgingly accompanied his fellow polemicist Christopher Hitchens to the event.

Many years later, Cockburn had a dramatic falling-out with Hitchens over the latter’s support for the Iraq War. In a 2003 CounterPunch newsletter column, Cockburn recalled Horowitz complaining at the symposium that “he had never been allowed to go to Doris Day and Rock Hudson movies, but rather was forced to sit through uplifting Soviet features. If only he’d been allowed to watch Pillow Talk…And of course, among the ironies is that Horowitz and Hitchens are now ideological bedfellows.”

Like Horowitz, Hitchens had been a Trotskyist in his youth who, toward the end of his life sadly, embraced neo-conservatism and Islamophobia. (Hitchens also wrote an article in the Los Angeles Times declaring the Panthers guilty of Van Patter’s killing, though it included a glaring error describing the accountant as African-American.) However, Horowitz’s transformation into an anti-Muslim bigot likely had more to do with the question of Zionism.

Even when he was a leftist, Horowitz was an admirer of the Zionist socialist and Israeli philosopher Martin Buber who argued for equality between Jews and Arabs within a bi-national state, paradoxically opposing the settler colonial project while also supporting it. Meanwhile, his intellectual guru Isaac Deutscher, an atheist who initially opposed Jewish nationalism, published an essay in 1958 called “Message of the Non-Jewish Jew” which, although critical of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, expressed sympathy for its necessity to exist.

The New Left’s relationship with Zionism was similarly complex and these contradictions came to a head during the Six-Day War in 1967 when some influential thinkers, like Herbert Marcuse, controversially defended Israel. During COINTELPRO, the FBI tried to sow division within Ramparts over the Arab-Israeli conflict, as much of its masthead consisted of writers of Jewish descent.

This included the Mandatory Palestine-born columnist Sol Stern, whose own deviation to the right began after the left’s response to the Arab-Israeli War. While some in-house staffers like Robert Scheer were highly critical of the Jewish state, others such as Maurice Zeitlin were openly pro-Zionist.

A chunk of the magazine’s financing came from Stanley Sheinbaum, an economist with deep pockets who contributed to many social causes over the years, including the legal defense of whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg after the release of the Pentagon Papers. Sheinbaum later played an instrumental role in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, initiating diplomatic talks with Yasser Arafat that ultimately brought about the Oslo Accords. (Ironically, Warren Hinckle left Ramparts in 1969 to start Scanlan’s Monthly with journalist Sidney Zion, who revealed Ellsberg’s identity as the source of the leak. Thereafter, Scheer took over as managing editor until he was ousted in a power grab by Horowitz and Peter Collier in the magazine’s final years.)

Sheinbaum first became associated with Ramparts when he co-authored a scoop in April 1966 with Scheer, Stern and Hinckle on the scandalous entanglement of Michigan State University (MSU) in the Vietnam War. “The University on the Make” recounted how, from 1955 to 1962, MSU was contracted by the U.S. State Department through the International Cooperation Administration [predecessor to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)] to provide “technical assistance” to the corrupt and repressive South Vietnamese government under President Ngô Đình Diệm.

In the mid-1950s, Sheinbaum was on the MSU faculty as an economics professor and was assigned to coordinate the university’s Vietnam Advisory Group (MSUG). MSUG helped train the fledgling national police force and advised Diệm’s unstable regime in public administration and economic development.

In the process, Sheinbaum uncovered that the school was acting as a front for CIA counterinsurgency operations and immediately resigned from the MSU Vietnam Project in disgust. Years later, Scheer stumbled upon MSUG while doing research on U.S. involvement in Indochina and Sheinbaum agreed to be a source for the investigative piece on the university’s collusion with the CIA. In late 1968, when the magazine nearly folded due to Hinckle’s financial mismanagement, Horowitz came up with the idea to file for an early version of Chapter Eleven bankruptcy and Sheinbaum became an investor.

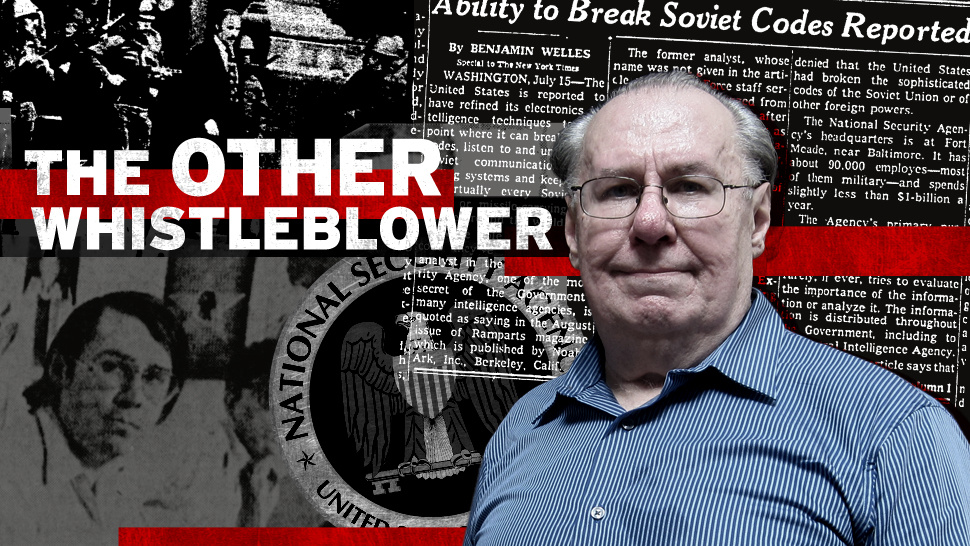

Deep dives into espionage became the periodical’s forte and Horowitz’s biggest contribution to that reputation came in the summer of 1972 when a 25-year-old Air Force veteran and intelligence analyst for the then-unrevealed National Security Agency (NSA) contacted Ramparts. Motivated by Daniel Ellsberg’s release of the Pentagon Papers, Perry Fellwock granted an interview to Horowitz and Collier under the pseudonym “Winslow Peck” to blow the whistle on the existence of an invisible and omnipresent spy agency with a budget exceeding that of the CIA.

The NSA was originally established in 1952 by President Harry S. Truman, and its existence was purposefully kept hidden from the public. Because of its top-level secrecy, the NSA was colloquially referred to as “No Such Agency” within the intelligence community. In the late 1960s, Fellwock had worked at an NSA listening post in Istanbul, Turkey, where he monitored Soviet communications until he left the confidential agency to enlist in the Air Force.

After serving in Vietnam, the Missouri native returned to the U.S. to resume college but dropped out to join the anti-war movement after the Ohio National Guard massacred four unarmed student demonstrators on the Kent State University campus. Still riddled with guilt over his time at the NSA, Fellwock reached out to Ramparts to share his story. Just months after the Watergate scandal erupted, Horowitz and Collier sat down with Fellwock who exposed several startling truths.

When Fellwock became an eavesdropper for the NSA, he assumed his confidential occupation was in the interest of world peace. Instead, he discovered the disturbing reality being concealed from the American people. Not only did Fellwock witness massive corruption working at the “Puzzle Palace,” but he soon learned the real reason it was kept a secret from the public. Its classified nature was not due to its function within the security apparatus, but the completely unchecked and panoptic extent of its surveillance.

In the Q&A session with Ramparts, Fellwock claimed the threat of Soviet expansionism had been deliberately overblown in order to enlarge the U.S. military budget. He also maintained that the NSA was unconstitutionally monitoring the domestic telecommunications of American citizens. On top of that, the U.S. was even spying on its own allies abroad. The latter was in violation of the UKUSA Agreement, a treaty for mutual cooperation in signals intelligence (SIGINT) to which the U.S., UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand (the “Five Eyes” alliance) were privately signatories.

ECHELON is the code name for the worldwide SIGINT network operated by the five English- speaking countries that was created to keep tabs on the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc. In addition to making the NSA’s mass surveillance system known, Fellwock warned that it had broadened its capacity to collect electronic communications globally.

Not long after Fellwock spilled the beans, the Church Committee investigation into misconduct by intelligence agencies led to the passing of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) to regulate government overreach in wiretapping, a federal law later violated by the George W. Bush administration after 9/11. He also confirmed that Israel’s attack on the USS Liberty during the Six-Day War was not accidental and that the Lyndon B. Johnson White House covered it up.

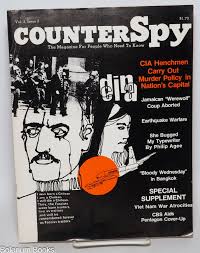

However, the long list of leaks in the bombshell interview was not without its share of exaggerations, namely his questionable claim that the NSA had cracked all Soviet code systems. In the ensuing years, the ex-NSA analyst helped to launch CounterSpy magazine, which at one time featured CovertAction Information Bulletin co-founder Philip Agee on its advisory board.

In a 2013 interview with the “first NSA whistleblower,” amid the Edward Snowden revelations, Fellwock professed that Horowitz and Collier misled him about the Ramparts story by including his overstatements and said he thought the two “were never truly part of the left.”

Horowitz was not the only former New Leftist to become a right-winger, nor was he the sole individual associated with Ramparts to go off the reservation. In fact, more than a few staff writers followed a similar political trajectory, including Collier and Sol Stern, as well as their mutual ex-comrade and Horowitz’s childhood friend, historian Ronald Radosh.

The magazine also employed a young Washington correspondent by the name of Brit Hume, who went on to become a Fox News pundit. It was Stern’s 1967 article which blew the lid off the CIA’s subterfuge with the National Student Association and connected it with earlier findings in The New York Times regarding the agency’s subsidizing of the Congress for Cultural Freedom.

Incredibly, Collier went on to found Encounter Books, a conservative book publisher which took its name from the defunct literary magazine endowed by the CCF and edited by its founder, Irving Kristol (himself an ex-Trotskyist turned neo-conservative).

In his twilight years, Horowitz’s inner rebel re-appeared when he came out in support of Donald Trump, to the dismay of establishmentarians like Stern and Radosh who took out an op-ed in The New Republic denouncing their old friend as a MAGA cultist.

The New Left emerged from the political confusion following Khrushchev’s “secret speech” and the Soviet intervention in Hungary, the same credulity that led Horowitz to later confront his father when The Gulag Archipelago by Alexander Solzhenitsyn was published.

A movement sprung from half-truths and propaganda was destined for failure from the outset. Looking back, it is little wonder that Horowitz’s transition to the extreme right was catalyzed by an incident shrouded in the mystery of the CIA and FBI’s subversion of the New Left.

Ruth wrote: “Before the end of the 1950s, I had already seen: The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, The Grapes of Wrath, Citizen Kane, The Great Dictator, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The Red Shoes, Great Expectations, Beauty and the Beast, Shoeshine, Bicycle Thief, Kind Hearts and Coronets, All the King’s Men, The Inspector General, Born Yesterday, The Day the Earth Stood Still and The Lost Continent (a double feature I saw with my brother), The African Queen, Cheaper by the Dozen, An American in Paris, Showboat, Member of the Wedding, Singing in the Rain, Viva Zapata, High Noon, The Greatest Show on Earth, The Wild One, The Blue Gardenia, Shane, Stalag 17, The Moon is Blue, Houdini, Three Coins in the Fountain, On the Waterfront, Sabrina, A Star is Born, Dial M for Murder, Seven Samurai, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, Rebel Without a Cause, East of Eden, Marty, The Seven Year Itch, Picnic, and possibly Pillow Talk as well. And this is only the short list.” She wrote that, generally, “[m]y up-bringing had less doctrinal influence on my life than it offered inclusiveness of different peoples and optimism for the future. What I treasure is the warmth I felt inside our home where friends stopped in, discussed issues heatedly, and left as friends – that feeling of camaraderie, and the sense that we were all in a larger family moving together towards building a peaceful, racially integrated world with jobs, fair wages and working conditions for everyone…all that, and the freedom to find my own way in all things cultural.” ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

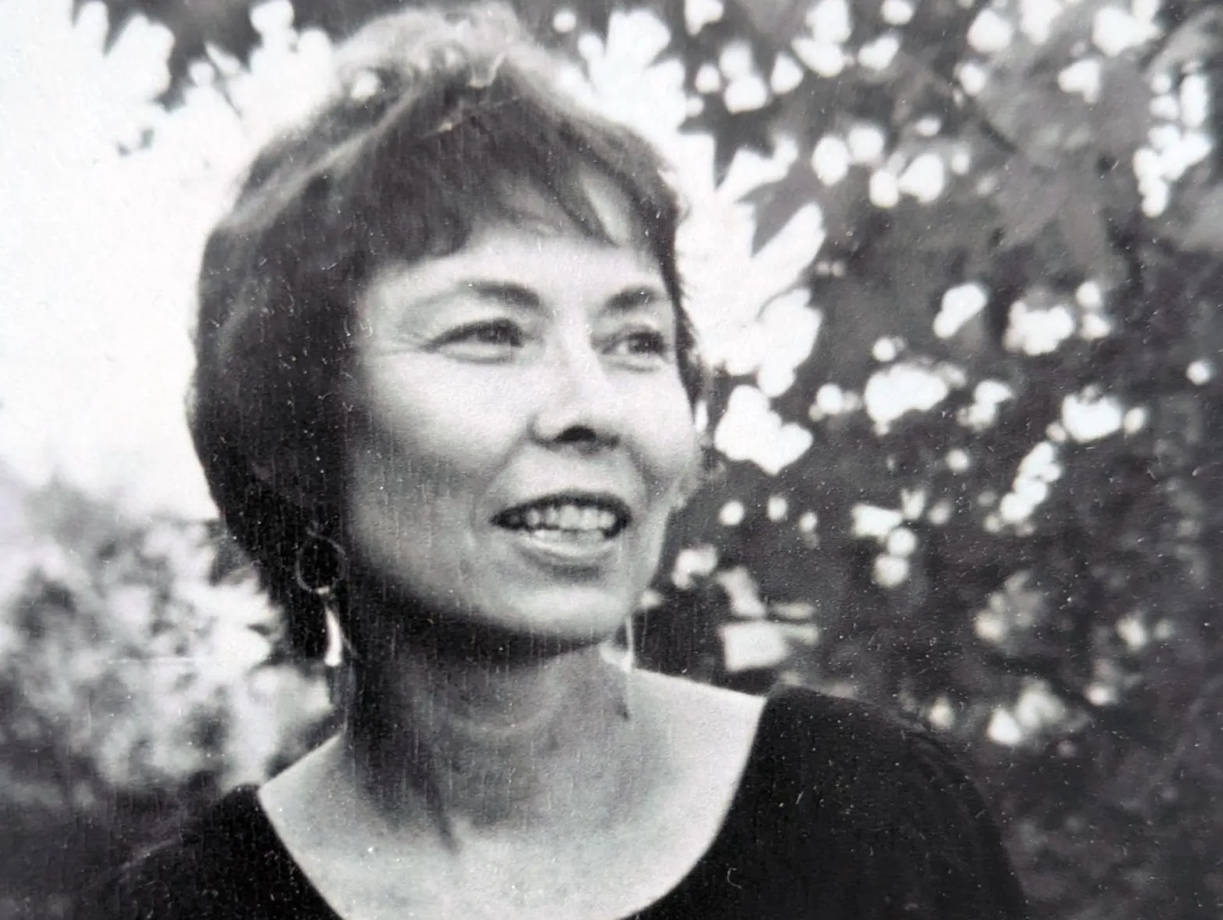

About the Author

Max Parry is an independent journalist and geopolitical analyst based in Baltimore.

His writing has appeared widely in alternative media and he is a frequent political commentator featured in Sputnik News and Press TV. He also hosts the podcast “Captive Minds.”

Max can be reached at maxrparry@live.com.

Here is a very detailed and thorough analysis of the USS Liberty story

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/history-and-overview-of-the-uss-liberty-incident

“He also confirmed that Israel’s attack on the USS Liberty during the Six-Day War was not accidental and that the Lyndon B. Johnson White House covered it up.”

Israel carried out the attack but the idea for it appears to have come from the Johnson White House:

https://lbjthemasterofdeceit.com/2022/06/07/on-the-55th-anniversary-of-the-day-the-u-s-nearly-kick-started-a-nuclear-war-with-the-soviet-union-6-8-1967/

The majority of people on the left are opposed to communism. People on the left support freedom of speech, freedom of the press and beneficial social programs. It is only a small number of people on the far left that support communism. So the the term left should not be associated with communism as it is primarily the far left that supports communism.