American embassy and CIA were complicit in their killings and the cover-up

On September 11, 1973, General Augusto Pinochet launched a fascist coup in Chile that deposed Salvador Allende, a democratically elected socialist who had nationalized Chile’s copper industry and enacted other measures designed to equalize wealth in Chile.

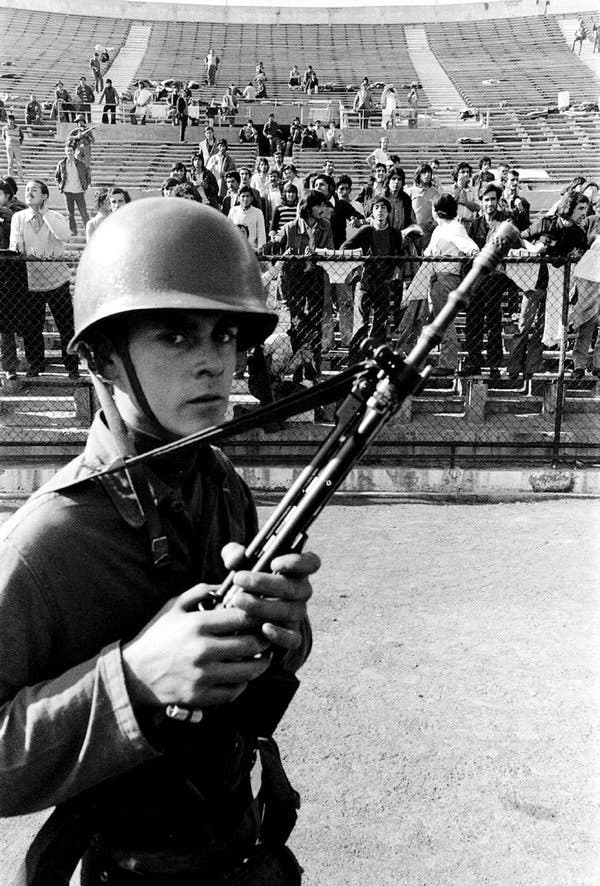

Supported by the Nixon administration and CIA, the fascist coup resulted in Allende’s death supposedly by suicide and was followed by violent pogroms targeting left-wing supporters of his government, many of whom were rounded up and brought to the National Stadium in Santiago before being executed.

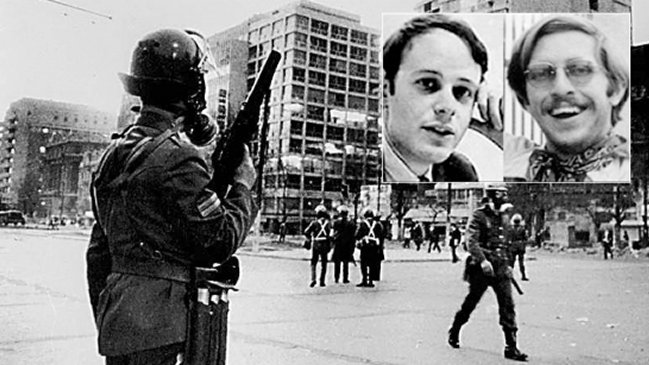

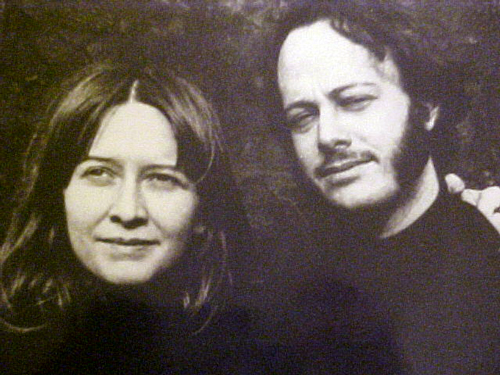

Among those murdered were two American leftists, Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi, Jr., who had lived in Chile and supported Allende’s government through involvement in media projects, leftist political groups and Chilean trade unions.

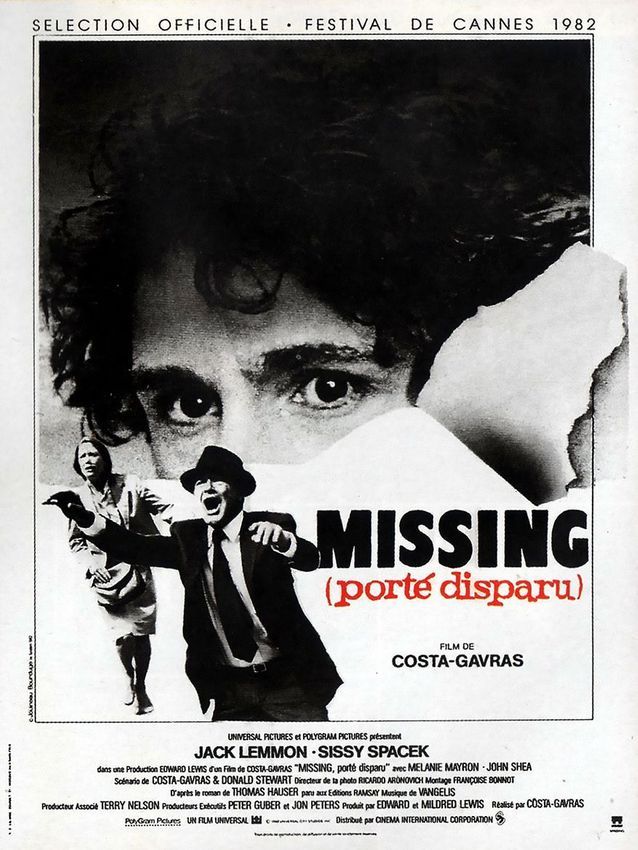

Horman and Teruggi’s cases were widely publicized in a 1978 book by Thomas Hauser that inspired Costa-Gavras’s 1982 academy award-winning movie, Missing.

Both the book and film followed the journey of Horman’s father Ed, a conservative New Jersey businessman, in search of the truth surrounding his son. Horman’s faith in the U.S. government was shattered as he uncovered a web of lies and cover-up.

Rafael González, a Chilean intelligence officer convicted as an accessory to the crime, told officials in the Italian embassy where he defected along with journalists that a CIA agent was in the room when Horman was interrogated by General Augusto Lutz, the head of Chilean army intelligence who ordered Horman’s execution because he knew too much about the U.S. role in the 1973 coup.[1]

Raúl Meneses Pachet, a Master Sergeant in the Chilean intelligence services, stated that he was told by other intelligence officers that there was a list of suspicious leftists given to the Chilean intelligence services by the U.S. Embassy.[2]

Chile, Not Spain, in Their Hearts

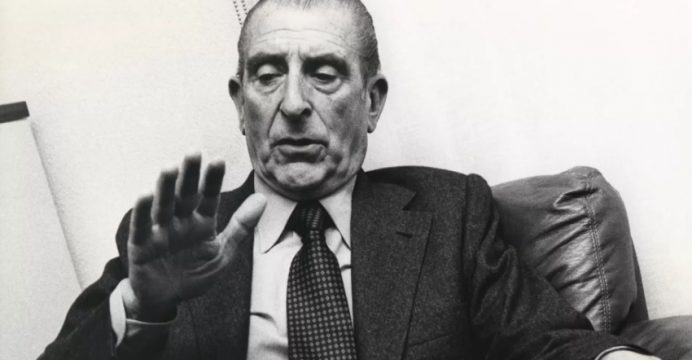

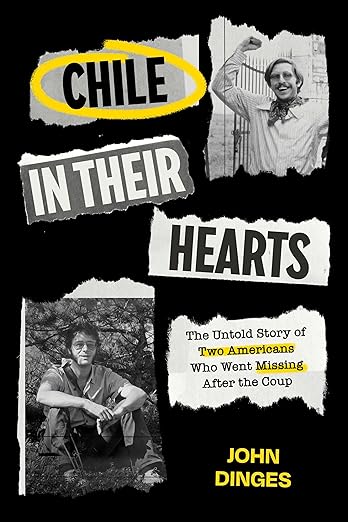

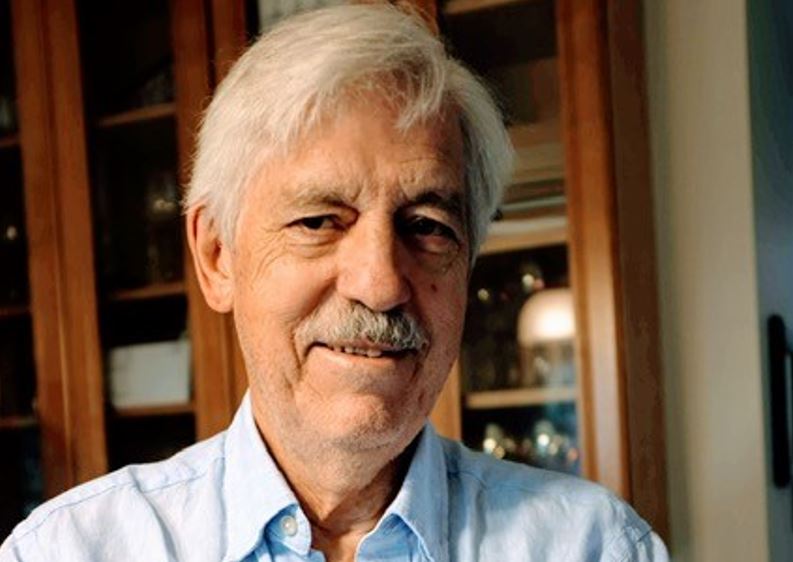

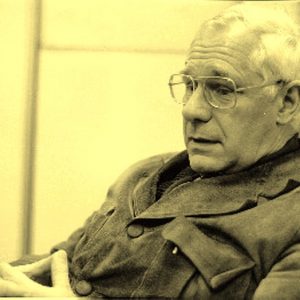

John Dinges is a Professor Emeritus of Journalism at Columbia University and former Washington Post correspondent who seeks to shed new insights on the Horman and Teruggi murders in his book, Chile in Their Hearts: The Untold Story of Two Americans Who Went Missing After the Coup (University of California).

Dinges was in Chile during 1973 and wrote a book on Operation Condor, a terrorist operation run by General Pinochet, with support from the CIA, that resulted in the torture and murder of thousands of leftists across South America in the 1970s.

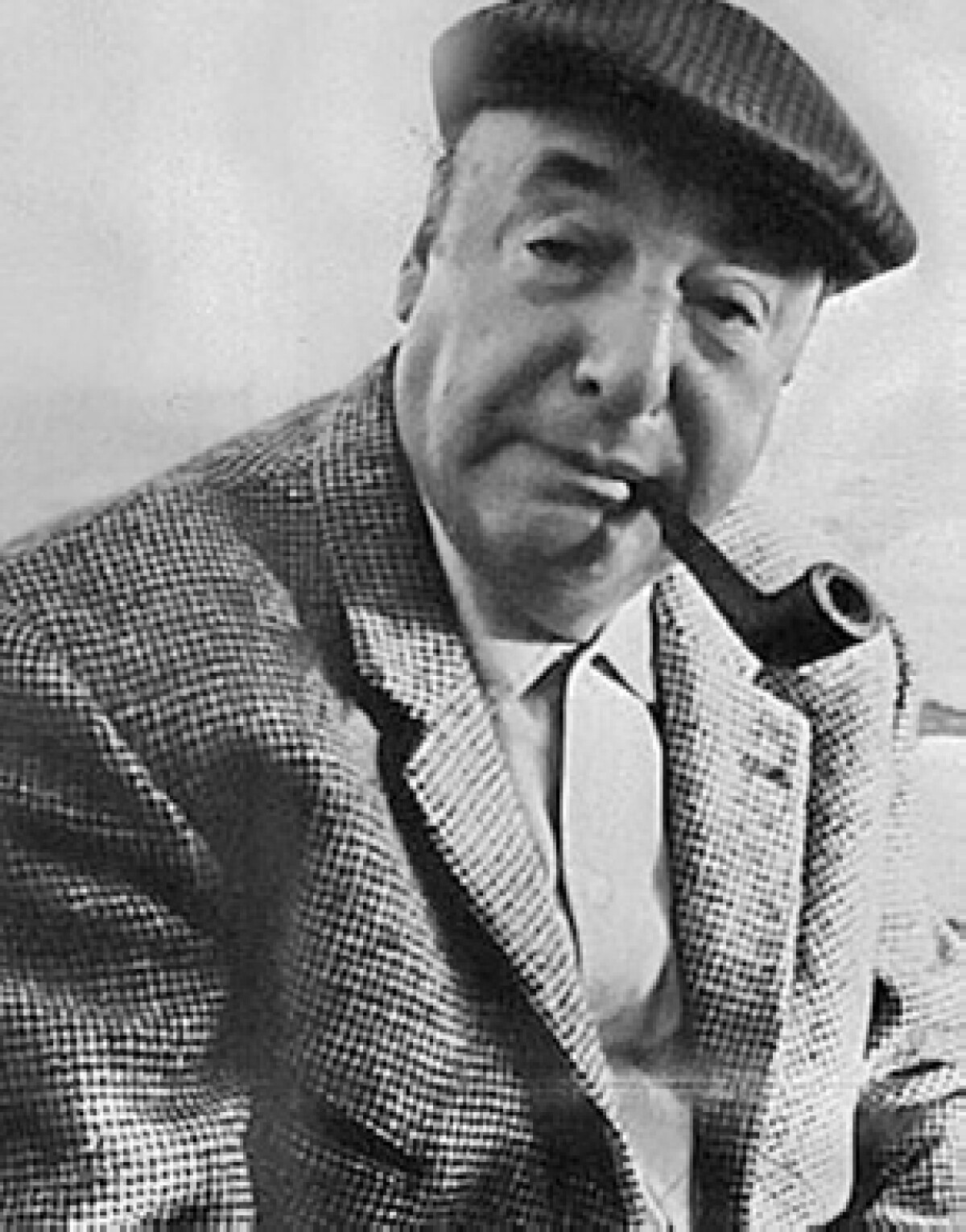

The title of Dinges’s book is a play on a famous Pablo Neruda poem, “Spain in Our Hearts,” written in 1936 about the Spanish Civil War.[3]

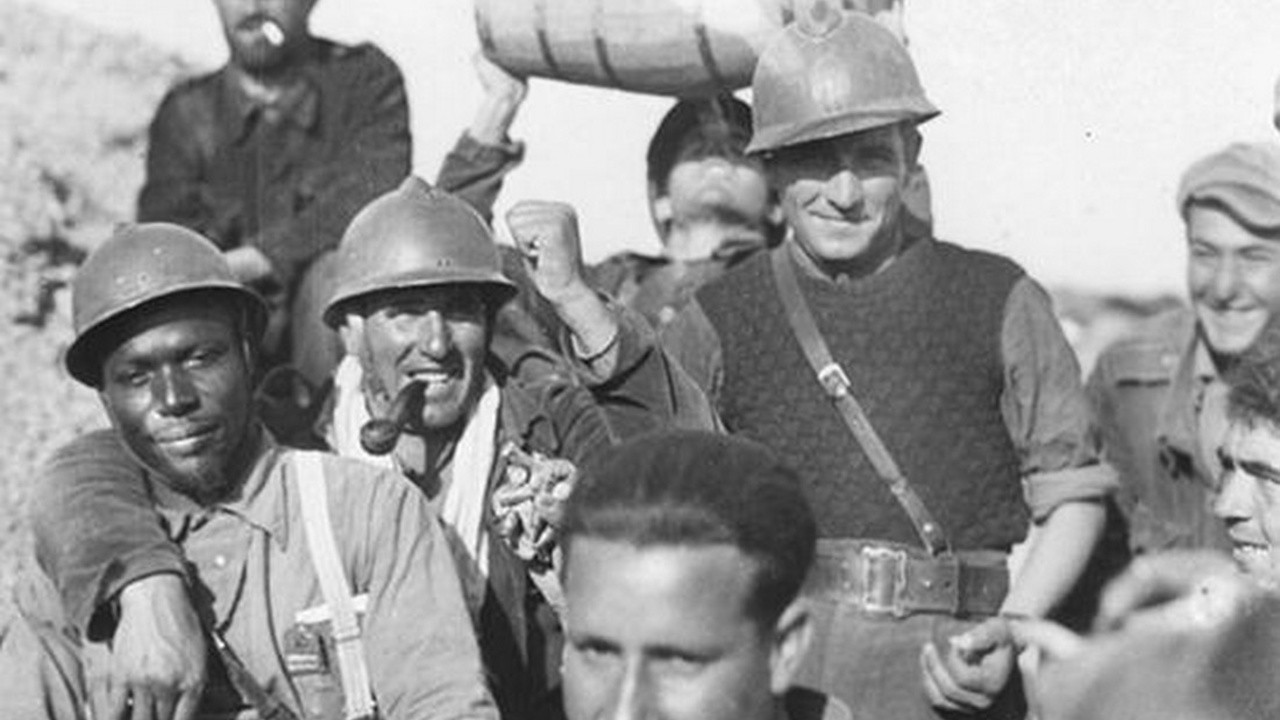

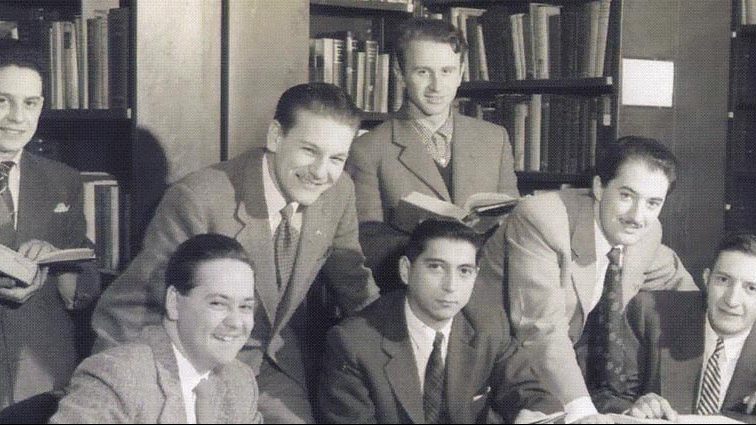

Dinges depicts Horman and Teruggi as the heirs of the left-wing idealists who went to Spain in the 1930s to fight with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade on behalf of a coalition of left-wing groups battling against Francisco Franco’s fascist forces.

Dinges writes that Charlie and Frank were “internationalists…in the noble ranks of so many others who traveled to another country to support and experience a revolution grander than themselves.”

Unfortunately, the forces of darkness and evil won out in Chile, like in Spain, and Charlie and Frank paid the ultimate price.

The two first developed their political consciousness in the 1960s movements for civil rights and against the Vietnam War. They were joined in Chile by refugees from other South American countries, like Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Uruguay and others that had experienced CIA-backed coups and military dictatorships.

Horman, age 30, was a Harvard graduate with a gentle manner and probing intellect.

He had participated in the Freedom Rides, and after graduation worked as a writer on an antiwar documentary, Napalm, about people in California protesting the presence of a plant in their community producing napalm for use in the Vietnam War.[4]

In 1968, Horman penned an article for the liberal Nation magazine about police brutality outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago where thousands had gathered to protest the nomination of cold warrior Hubert Humphrey.

After working for New York City’s educational TV station and a business magazine, Horman and his wife Joyce, a computer programmer, decided to travel around South America and support the radical experiment in social democracy that was taking root in Chile under Allende.[5]

After getting a job working for a local filmmaker, Horman began investigating the murder of General René Schneider, the constitutionalist chief of Chile’s army, who was seen as standing in the way of the plot to prevent Allende from taking office after his 1970 election victory.

Later, evidence came to light implicating the CIA and Henry Kissinger in Schneider’s murder, which was committed by Chilean General Roberto Viaux and General Camilo Valenzuela.[6]

The state-owned company that Horman worked for was headed by Eduardo “Coco” Paredes, who was one of the first to be murdered by fascist death squads after the September 11 coup.[7]

Only 22 when he arrived in Chile, Teruggi had grown up in the small, working-class town of Plainview, Illinois, and was exposed to liberation theology at his Catholic high school.

A skilled radio operator, he became a founder of the Cal Tech chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the leading campus progressive and anti-war organization in the 1960s, and attended the demonstrations outside the 1968 Democratic Party Convention in Chicago, where he was arrested during a guerrilla theater performance against police brutality.

After enrolling at the University of California at Berkeley, Teruggi began volunteering at the leftist magazine NACLA (North American Congress on Latin America), which published articles on political change in Chile and the rise of Salvador Allende.[8]

Hitchhiking to Santiago, Teruggi joined a revolutionary student organization that supported government expropriation of large latifundia, and a political party, Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR-Movement of the Revolutionary Left), that organized farm workers and the urban poor along leftist principles.[9]

During the day, Teruggi studied economics at the University of Chile and became an intern at a progressive think tank led by development economist André Gunder Frank.[10]

An Obstacle to Accomplishing U.S. Policy Goals in Chile

During a visit to New York a month before his death, Horman raised funds to buy weapons for a workers’ organization in Chile known as Cordones Industriales so they could resist a potential coup.

This could have been a reason why he was targeted for assassination, along with the fact that he had met a U.S. Navy engineer, Arthur Creter, who told him that “we came down to do a job and it’s done.”[11] Joyce Horman interpreted Creter’s statements as referencing the coup.[12]

A woman accompanying Creter overheard his remarks—which exposed U.S. covert activities—and allegedly told Patrick Ryan, second in command of the U.S. military group, who told Captain Ray E. Davis, chief of the U.S. military group and U.S. naval mission to Chile.[13]

A few days later, likely not by happenstance, Davis gave Horman a lift from Valparaíso to Santiago.[14] Missing suggested that, during the car ride, Davis confirmed Horman’s knowledge of U.S involvement in the coup and afterwards had him killed because he knew too much.

Davis was said to have passed information about him to the Chilean intelligence services, who acted on the tip.

John Dinges pushes back against that theory: He says that it hinges on the testimony of Chilean intelligence officer Rafael González, who recanted his story about a CIA officer being in the room when General Lutz ordered Horman’s execution, saying that he had invented the story to call attention to his efforts to flee Chile.[15]

Later, however, in a sworn affidavit in a lawsuit against Henry Kissinger, González recanted his retraction and asserted that what he said about the CIA agent in Lutz’s office was true.[16]

At a minimum, Davis and U.S. embassy officials and the CIA covered up Horman and Teruggi’s murders. Failing to press for investigations of what happened, they deceived the families of the victims and publicly repeated Pinochet’s claim that Horman and Teruggi were involved in criminal acts and were killed by leftist snipers—even after internal State Department investigations concluded that Horman and Teruggi had been executed by the Chilean military.[17]

Henry Kissinger had instructed U.S. Embassy officials to defend the regime that had overthrown Allende, whose progressive experiment was considered a dangerous “communist” model.

CIA operative James Anderson was a key embassy point person tasked with investigating Horman and Teruggi’s disappearances.[18]

He worked under General Consul Frederick Purdy, who counted among his circle of Chilean contacts Michael Townley, a CIA and Chilean intelligence agent from Waterloo, Iowa, who was convicted for his role in planting a car bomb in Washington, D.C., that killed former Chilean Foreign Minister Orlando Letelier and Ronni Karpen Moffitt, a fundraiser for a left-wing think-tank, in 1976.

The U.S. ambassador to Chile at the time of the coup, Nathaniel Davis, had presided over a diplomatic team that was “deeply embedded with then opposition to Allende, including far-right groups working to foment unrest and undermine the economy,” according to Dinges.[19]

Dinges writes that Davis “treated the murders of two Americans as an obstacle to accomplishing U.S. policy, which was to shepherd the new military government into international respectability. More than murders to be investigated, the deaths of Horman and Teruggi were a problem to be finessed and an obstacle to be removed. Following his lead, the U.S. government persistently refused to acknowledge—for almost 20 years—that Chile’s military had killed them.”[20]

Planned Military Operation

Eyewitness accounts indicated that Horman was the target of a planned military operation that had resulted from intelligence information—likely provided by the CIA—that presented him as an extremist.[21]

Detained on September 17, 1973, by a Chilean army unit at his house located in the heart of a Cordones factory area, his body and that of six labor leaders were delivered to the morgue less than 24 hours later after having been executed in the national soccer stadium.

The cause of Horman’s death was multiple gunshot wounds to the head.[22]

Teruggi’s address may have been given to Chilean authorities by the FBI, which had conducted an investigation of Teruggi and obtained the address where he was arrested.[23]

Teruggi’s connection to activists in Germany who helped U.S. soldiers to desert the U.S. military—which the FBI reported on—may have set off alarm bells among Chile’s intelligence services because the MIR was trying to encourage defections among Chilean soldiers.

The latter were tortured and killed if they were caught collaborating with MIR—with which Teruggi associated.[24]

When they entered Teruggi’s home, police were put off by his collection of Marxist books, including a complete set of Lenin’s writings and a recently acquired biography of Leon Trotsky, which they packed up and took as evidence.[25]

Witnesses later testified that they saw Teruggi at the national soccer stadium after he had been tortured with electroshock and so brutally beaten that he was semi-conscious.[26]

A Chilean court convicted Captain Pedro Espinóza, an intelligence officer in charge of interrogations at the soccer stadium, of the murder of Horman and Teruggi.[27]

Dinges’s investigation identified several other key Chilean officers who were involved, including Colonel Fernando Grant Pimentel, who dispatched the military unit to detain Horman, and Lieutenant Enzo Cadenasso and Lieutenant Colonel Roberto Soto Mackenney, who were also directly involved in kidnapping him.

A Wound in Our Hearts

Chile in Their Hearts shows the deep U.S. complicity in the fascist coup and violence in Chile. Under Pinochet, Chile became an experiment in radical free-market economics as Milton Friedman and other Chicago Boys descended on the country, with calamitous consequences.[28]

The U.S. had set the groundwork for the coup in the 1960s by financing Chile’s police forces and cultivating ties in the armed forces that were expanded upon after a campaign of economic sabotage and terrorism helped turn part of the population against the Allende government.[29]

The same tactics are being adopted by the U.S. today in countries targeted for regime change run by governments with a leftist orientation or who seek to adopt an independent foreign and domestic economic policy.

John Dinges writes: “Chile is a great love, and what happened there was a great wound in our hearts.”[30] These words resonate even more today in an era of right-wing political dominance and ascendant fascism, which is on the march now in the U.S.[31]

John Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts: The Untold Story of Two Americans Who Went Missing After the Coup (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2025), 125, 145. Lutz subsequently died under suspicious circumstances. González recalled him saying: “This guy [Horman] knows too much, and we have another kind of information, so this guy has to disappear.” ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 162. ↑

Neruda was a Chilean poet who died of cancer after the Pinochet coup. Dinges raises suspicion of foul play in his death.

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 15. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 19. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 164, 165; Peter Kornbluh, The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Acountability (New York: The New Press, 2013). ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 77. Paredes, a close ally of Allende, had headed the investigative police. The Pinochet regime claimed that his murder resulted from Paredes allegedly attacking a Carabinero patrol car and that he had been killed while “fleeing.” A documentary that Horman worked on presented Allende’s revolution sympathetically and went into the class fissures in Chilean society and oppression of the Indigenous population dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries. ↑

Subsequently, Teruggi helped form a Chicago Area Group on Latin America with Roger Burbach, which brought together anti-war Peace Corps volunteers who wanted to support Third World social movements. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 29, 32. MIR was founded in 1965 in emulation of Cuba’s success and the ongoing guerrilla campaign of Ernesto “Che” Guevara. One of MIR’s top leaders was Salvador Allende’s nephew, Andrés Pascal Allende. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 32. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 68. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 144. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 169. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 69. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 133. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 153. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 100. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 101. ↑

Idem. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 101, 102. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 86, 123. The military at the time was encouraging people to inform on their neighbors who may be attempting armed resistance to the fascist takeover. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 89. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 162. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 162. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 91. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 93, 94, 162. Because they had beaten Frank so badly, the officers at the stadium shot him with a burst of machine-gun fire though tried to cover up what had happened in order to avoid trouble with the U.S. government. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 82, 124. ↑

See Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007). ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 95. See also Jeremy Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression: Police Training and Nation-Building in the American Century (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012); Kornbluh, The Pinochet File. ↑

Dinges, Chile in Their Hearts, 218. ↑

See, e.g., Michael Steven Smith and Zachary Sklar, eds., From the Flag to the Cross: Fascism American Style (New York: OR Books, 2025). ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.