Public relations machine transformed hard-line jihadists—whom Hillary Clinton famously called “hard men with guns”—into valiant freedom fighters in the eyes of the U.S.-UK public

[This is the third part of a series. Part I can be found here and Part II can be found here.—Editors]

Imagine if an armed rebellion took place in the United States against the federal, state and local governments.

Given 21st century U.S. politics, there would probably be armed groups formally or informally associated with the Three Percenters, Oath Keepers, Boogaloo Boys, Constitutional Sheriffs movement, Christian nationalist groups, and various independent right-wing militia movement who would fight for or against the government depending on who holds various political offices at the time.

There may also be armed pro- or anti-government left-wing rebels connected with the Socialist Rifle Association or various communist parties, as well as Black nationalist or Chicano groups of various political persuasions, or groups organized around their locales rather than ideology, religion or ethnicity.

Don’t worry about the political content of the rebels for now. Think logistically. Imagine some rebels took over a section of, for example, the upper Midwest (in a state like Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Minnesota), and held onto it for years. The civilians living in those places would need to maintain some degree of normal life to survive while the conflict drags on. The rebels would have to communicate with and govern their peoples and territories to maintain or expand their power.

Now imagine the Chinese, Russian, Iranian, Cuban and Canadian governments coordinated to support anti-government rebels in the U.S. because they thought that supporting the rebels would be in their interests. Maybe some of these foreign powers want regime change in the U.S., or want to make the U.S. weak and (more) divided, or want to take territory or resources from the U.S.

Imagine they spend billions of dollars providing military training, weapons, supplies and money to whichever rebel faction(s) they think will best advance their goals. Not only that, but they also provide cutting-edge communications equipment and media training to the rebels on how to use cameras, edit footage to create convincing narratives, build a positive brand for themselves, and use social science methods to determine target audiences and reach them via local and international media.

Foreign powers funnel weapons, money and equipment through the Canadian border to their allies, and some rebels they bring into Canada or Cuba to receive training and other things they need. Imagine Canada militarily invades and occupies pieces of U.S. soil to fight one faction or protect another, similar to how Türkiye invaded Syria to fight Kurds and support Sunni Arab rebels.

These foreign governments pay to send agents into rebel-held territory and set up, train and fund newspapers, radio and TV stations, journalists and websites, as well as identify rebel spokespeople, organize interviews with local and international media, and coach them through the process.

These governments also run public opinion polls and focus groups, collect and analyze data to assist rebel administrations and military plans, and set up rebel-aligned city councils, police forces, schools, sanitation services, hospitals and health clinics, emergency first responders, and other essential services.

The foreign powers do their work secretly in tandem with the rebels to bolster an overarching narrative of heroic citizens fighting against the odds for freedom and democracy against a corrupt, evil government. They manage to create a media ecosystem with a wider reach than the U.S. government both internationally and within large swaths of U.S. territory.

Economic warfare significantly degrades the U.S. economy to the point that foreign-funded rebel media and civil society employees get paid several times more than U.S. government soldiers.

It is far from a neat parallel, and the scenario is unlikely for many reasons, but this hypothetical U.S. civil war and foreign intervention paints a picture roughly analogous to what Syria experienced with its own civil war from 2011 to 2024.

This article will examine the purposes, methods and achievements of the largely covert, multi-billion dollar Western soft-power interventions in the Syrian Civil War. It will focus on the information warfare and public relations management aspects of the intervention, and what significance can be established from the little information that is publicly available on the topic.

This article and a subsequent article will also highlight how these interventions facilitated and covered up sectarian violence and theocratic repression by forces fighting the Syrian government.

Purposes of the Soft-Power front

As explained in Part II of this series, the soft-power program by the U.S. and its allies was not simply tasked with pushing a propaganda narrative of independent, liberal, democratic rebels against an evil dictatorial state. The program also had to help the rebels govern their territories.

Essentially, they sold an ideal image of the rebellion to local and international audiences while simultaneously working with rebels on the ground to bring reality closer to that ideal image. This was no small task because the reality of the rebellion was far from the image of liberal freedom and democracy that the U.S. and its allies wanted to sell.

Not only that, but the soft-power players in Syria also had to contend with fickle and divided supporters both within the U.S. and between the U.S. and its allies. Some elements in the Obama administration such as President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden were more cautious in approaching Syria, while others like Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of State John Kerry advocated more radical intervention.

The soft-power support front helped these factions negotiate and find consensus by increasing their leverage over the situation and keeping their options open. It reassured the moderates that it would manage where the money, training and weapons went, make the “moderate” rebels more moderate and better fighters, and facilitate preparations for a responsible rebel takeover or a negotiated settlement. Put simply, it would give them influence but also make sure that they “don’t do stupid shit,” as Obama famously said regarding U.S. foreign policy in West Asia.[1]

For the hardliners it offered continuous pressure on the Assad government and built the narrative case for escalation should they decide to adopt a more radical intervention.

Developing a Propaganda Machine

This billion-dollar media and civil society program involved a plethora of contractors and subcontractors. The firms involved came mainly from the U.S., UK and Turkey but also the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Jordan and Lebanon. These contractors specialized in public relations, consultancy, data analytics, media production, procurement and monitoring and evaluation.

The most important UK contractors included the Dubai-based international conflict management and research consultancy, Analysis Research Knowledge (ARK) and a London-based data science, engineering and development consultancy called The Global Strategy Network (TGSN). TGSN was founded and directed by Richard Barrett, former director of global counterterrorism at the British Secret Intelligence Service (popularly known as MI6).[2] ARK and TGSN partnered closely during the Syria intervention.

The UK first organized its propaganda through an outlet called Basma that was ostensibly grassroots but, in reality, was developed by ARK, which the latter developed into a multimedia platform called Moubader.[3] ARK alone reported delivering $66 million for Syria programming on behalf of international donors by 2015.[4]

ARK’s team proudly boasted its “extensive experience managing programmes and conducting research funded by many different governmental clients in Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Yemen, Turkey, the Palestinian Territories, Iraq and other conflict-affected states.”[5] ARK’s Syria programming developed from years of experience in soft-power operations throughout West Asia, and the resumes included in the documents of ARK and other contractors reveal that key personnel on the Syria operation had worked on similar projects in at least half a dozen countries.

Several key employees had experience with soft-power operations prior to Syria, in Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, often in that order.

ARK and its partners, which often referred to themselves collectively as “the consortium” in internal documents, designed propaganda and media strategies for the Free Syrian Army (FSA) to improve its media profile as early as 2012. ARK reported that extremist and pro-government forces dominated the 2013 digital media space, and that they had studied the media capacities of extremist groups to mold the FSA’s online presence. They worked to distinguish the FSA’s advertised values, behavior and agenda to appeal to target audiences.[6]

ARK designed and optimized websites for the FSA and the Supreme Military Council (SMC), the FSA’s command structure from 2012 to 2014. ARK created “a ‘re-branding’ of the SMC” to distinguish it “from extremist armed opposition groups and to establish the image of a functioning, inclusive, disciplined and professional military body.”

ARK identified “four distinct audiences for this project: the FSA/SMC; the general population inside Syria; the Syrian regime; and the international community.”[7]

Perhaps the most secretive work of the consortium included their studies of violent extremists to calibrate their pro-FSA propaganda. ARK created a “sister company,” The Stabilisation Network, to carry out this work, and their documents remain out of public reach.

To their government benefactors, Western contractors advertised their abilities to organize, brand and manage the Syrian opposition as something that had at least a façade of unity, liberal values, and effective fighting abilities. The contractors then sold this story to the FSA units, the Syrian people, Western audiences, and the international governments providing arms, training and money to Syrian rebels.

ARK ran social media accounts for the White Helmets, whose prolific rescue and service videos put a humanitarian and liberal face on the Sunni Arab armed opposition. Through Twitter (now called X), ARK began collaborating with The Syria Campaign (TSC), a British lobbying and public relations NGO started in 2013 that was founded by a corrupt billionaire oil magnate and major donor to the Tory Party, Ayman Asfari.[8]

ARK reported that TSC’s social-media presence gained the White Helmets “a number of international TV features and articles.”[9]

Recognizing the White Helmets’ potential to serve as a face for the rebel cause that Western audiences could get behind, TSC in 2014 selected the White Helmets “to front its campaign to keep Syria in the news.”[10] Support for civil society and media groups like the White Helmets was publicly, if vaguely, acknowledged by Western governments.

However, the leaked UK contractor documents show that such activities were integrated into a U.S.- and UK-led hybrid warfare scheme.

Propaganda Achievements

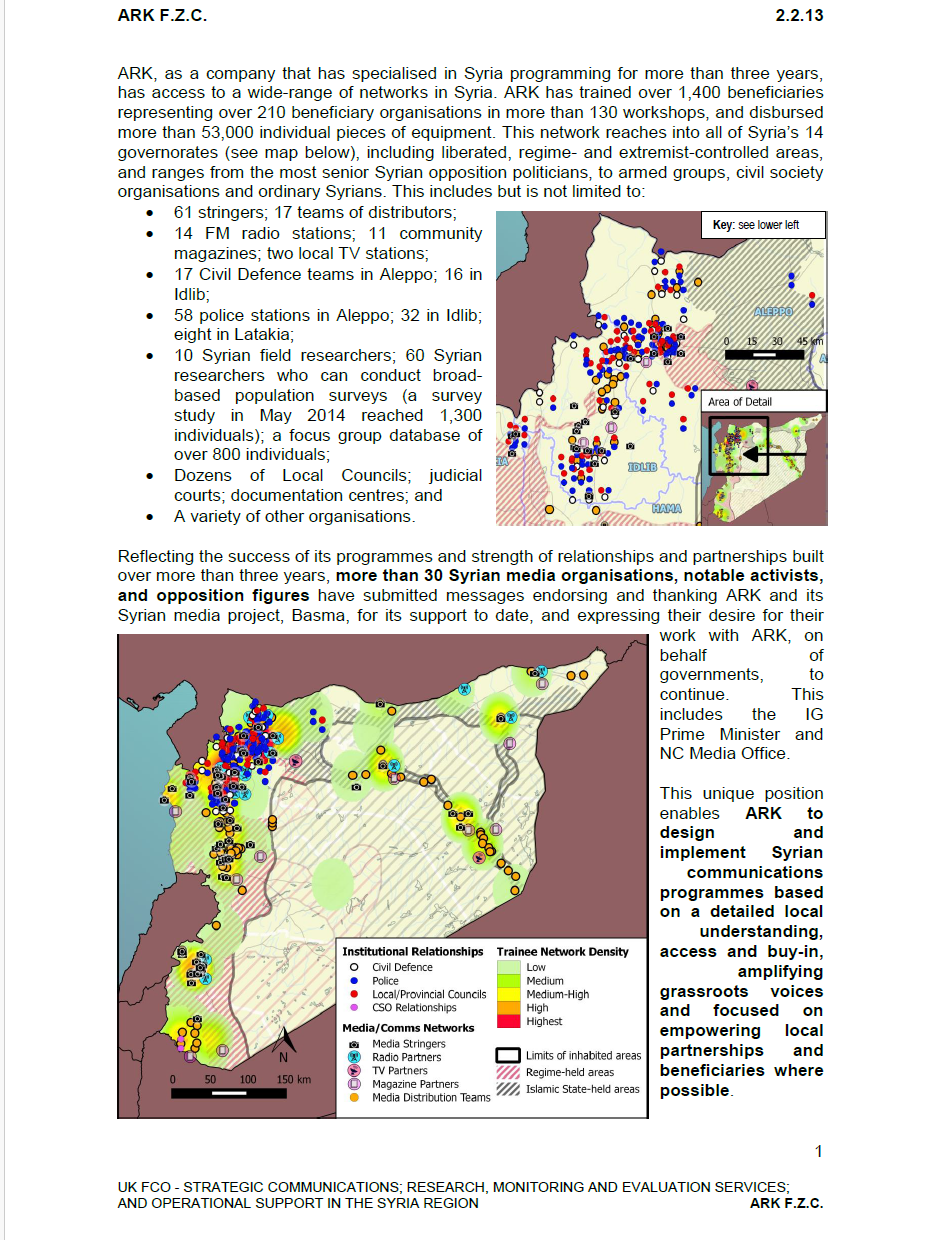

ARK claimed that it had trained more than 1,450 individuals and organizations and disbursed more than 54,000 pieces of equipment by 2015.[11] ARK’s network reached “into all of Syria’s 14 governorates,” including “liberated, regime- and extremist-controlled areas,” and ranging from “the most senior Syrian opposition politicians, to armed groups, civil society organisations, and ordinary Syrians.”[12]

From 2014 to 2017, ARK listed 97 stringers (free-lance journalists), 23 photographers, 49 distributors, 14 FM radio stations, 11 magazines, 2 TV stations, 3 media offices, and 8 training centers.[13]

Alongside their media resources, ARK listed civil society groups, including 17 civil defense teams in Aleppo and 16 in Idlib, and 60 Syrian field researchers able to produce “broad-based population surveys.” They also boasted of maintaining “dozens of Local Councils; judicial courts; documentation centers” and “a variety of other organizations” in their network.[14]

ARK selected and trained public relations leaders from the armed militias whom ARK would then promote “as go-to interlocutors for regional and international media.” Cultivated spokespeople would “echo key messages linked to the coordinated local campaigns across all media, with consortium platforms able to cover this messaging as well and encourage other outlets to pick it up.”[15] ARK and TGSN claimed they could distribute their pro-rebel, anti-Assad media through their “well-established contacts with numerous key media organisations including Al Jazeera, Al Arabiya, Orient, Sky News Arabic, CNN, BBC, BBC Arabic, The Times, The Guardian, FT [Financial Times], NYT [The New York Times], Reuters and others.”[16]

Some claims and figures that the government contractors make in their internal documents are backed up by Western academic and government-funded research on media development in Syria. Public Western reports on the Syrian media ecosystem and audience consumption patterns reveal that satellite television was the most dominant source of news across Syria, and that audiences in opposition held areas consumed and trusted regional channels such as Al-Arabiya, Al-Jazeera, and Orient the most.[17] ARK and TGSN’s internal studies from 2017 concur with this assessment, naming Al-Arabiya, Al-Jazeera, Orient, and Sky Arabic as most trusted in their target audience analysis of media consumers in opposition-held areas.[18]

Western studies pointed out that newspapers and especially radio were underdeveloped outside of government-supporting outlets and government-held areas early in the war.[19] However, they also reveal that, by 2016, residents of Idlib Governorate reported unusually high media-penetration levels, indicating greater access to Syrian, regional, and international television, newspapers, websites and social media than any other Syrian province, and second only to Hama in access to radio.

Of course, Idlib Governorate became the stronghold of the Abu Mohammed al-Julani (legal name Ahmed al-Sharaa) al-Nusra Front, the al-Qaeda franchise in Syria, after Nusra and their Salafi allies captured Idlib City in March 2015. From Idlib, Jolani built his regime and launched his November 2024 offensive that toppled Assad and won Jolani the presidency of Syria.

Idlib Governorate, where many different armed opposition factions came to be housed after 2016, also happened to be where the UK FCO consortium was most active for the longest time.[20] Western agents were thus instrumental in developing a media ecosystem with further reach than the government-held areas of Syria in a province that happened to be run by theocratic and sectarian rebels.

Agencies of the covert Western consortium ran their own platforms like Basma as well as the digital media presence of some opposition factions, and they simultaneously organized secret partnerships with regional media and Syrian opposition outlets already benefiting from international, largely Western, support. By 2017, ARK and TGSN reported that they had produced and placed more than 2,000 news reports, vox pops, documentaries, and other products on Orient, Al-Arabiya, Al-Jazeera, and Sky Arabic, and promised at least weekly placements on those platforms in future projects.[21]

TGSN partnered with Syrian opposition media networks including Sham News Network and Syria Media Action Revolution Team (SMART), which operated Hawa SMART radio and SMART TV, as well as other TV, radio, and online outlets like Halab Today (aka Halab al-Yawm), ARTA FM, Rozana FM, Watan FM, and Radio Fresh.[22]

Another consortium UK contractor, Albany Associates, named prominent multimedia platform Enab Baladi as an intimate consortium partner.[23]

Western researchers named these outlets (many of which were also supported by Western governments and media development NGOs) as some of the most popular in Syrian opposition-held, contested and refugee areas throughout the war.[24]

Foreign powers had a significant influence on regional television that anti-Assad Syrian audiences primarily relied on for information, while simultaneously building and coordinating a wide array of multi-media, anti-Assad Syrian outlets that relied on foreign funding to operate in rebel-held spaces and neighboring countries.

Significant international news stories and media products grew out of this propaganda program.

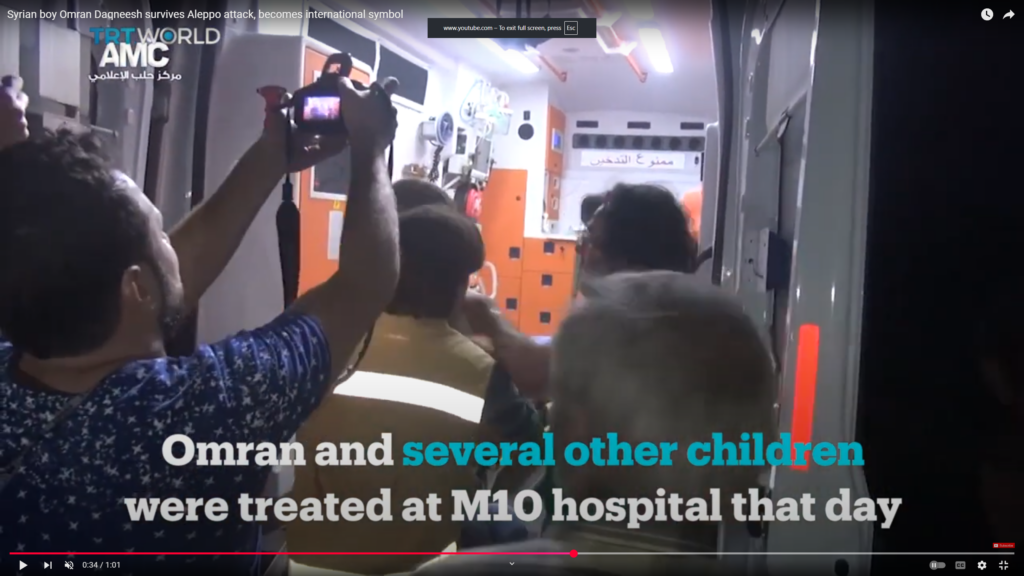

In August 2016, one key Western-supported outlet, Aleppo Media Center (AMC), made major international headlines when its stringers recorded now-famous images of five-year-old Omran Daqneesh as he was placed in an ambulance after an airstrike that hit his family home in rebel-held East Aleppo. The images of the boy sitting in a state of shock with blood covering half his face and dust covering the rest of his body, became a cause célèbre that many pro-rebel media, politicians, and influencers used to demand humanitarian intervention in the Syrian war.

The striking image helped the story go viral, but it could not have spread so quickly and effectively without money, equipment, training, infrastructure and international networks provided by Western powers. The boy’s experience may have never been filmed in the first place without such support, like so many unworthy victims of violence in the Syrian war whose suffering was not useful for foreign interests.

An AMC photojournalist, Mahmoud Raslan (sometimes spelled Rislan), who was also a correspondent for Al Jazeera Mubashir, was credited with capturing the viral images of Omran and he shared his personal story in several mainstream news articles on the event.[25]

Raslan’s politics and background sparked a minor scandal, however, when people looked into his social media.

It turned out that Raslan had praised suicide bombers on social media and, in August 2016, around the same time he photographed Daqneesh, Raslan had posted a friendly selfie with fighters of the U.S.-armed-and-trained Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement.

Less than a month earlier, in July, two al-Zenki fighters from that selfie had filmed themselves in a group capturing a wounded 12-year-old Palestinian boy and sawing his head off with a knife.[26]

AMC journalists also spread inaccurate stories to Western researchers that downplayed the role of al-Nusra and other sectarian groups while insisting that supposedly liberal, Western-approved groups had led the rebel fighting in Aleppo City.[27]

The Western propaganda program sought to use local Syrians as the primary faces and laborers of the propaganda, especially because Western journalists stopped going into rebel-held Syria for fear of being kidnapped or killed by rebels. Local Syrians were cheaper, could move more freely and, if some rebels killed or kidnapped them, it was less likely to make embarrassing international headlines.

Local Syrians could also emanate more authenticity if they were trained and equipped properly.

In one internal document ARK bragged that its Basma media “products” were “a radical departure to previous multi-million-dollar programming in Iraq and Afghanistan in that it has raised and trained local national staff as the core element of the capability,” which “resulted in a resonance of product” (emphasis in original).[28]

Richard Barrett’s TGSN directly ran the Revolutionary Forces of Syria Media Office (RFS), which integrated Western pop culture trends such as Pokémon Go, Marvel’s Avengers, and the Mannequin Challenge to create viral humanitarian and atrocity stories meant to appeal to Western audiences. Internal UK contractor documents identified RFS as the consortium’s most popular media platform, obtaining more than 608,000 Facebook followers before being shut down.

Note that the examples above from RFS and AMC centered in Aleppo City in 2016. The Western consortium was perhaps most active at that time and place because Aleppo City was then viewed as the most important battle of the war and the Assad government was in the process of retaking rebel-held eastern Aleppo.

Perhaps the most significant media product the Western consortium helped produce and distribute was the Oscar-winning 2016 documentary, The White Helmets, which was also centered in Aleppo in 2016.[29]

Significant Impact

The largely covert Western soft-power media and civil-society program made a significant impact on the media landscape of the Syrian conflict, shaping public discourse and understanding both in and out of Syria.

It facilitated communication that rebel groups could benefit from with international audiences, local civilians and other rebel groups.

Furthermore, it maintained a plausible narrative of a moderate rebellion against an evil dictator for those who wanted to believe it, while disciplining and confusing those who approached the narrative battles around the conflict critically.

The program became especially effective because many Western journalists stayed out of rebel-held Syria, meaning that covert propaganda agents and their local collaborators had almost exclusive access to the spaces being reported on. This arrangement made it difficult for Western audiences and journalists to get information about these places that was not substantially filtered by interested parties who were coordinated through a billion-dollar multi-government program.

On the ground, Western agents produced manipulative propaganda while also working with militias to help them improve their public relations and avoid embarrassing stories from coming out about them.

Within the U.S. administration and national security state, the covert soft-power program had benefits for both moderate and hard-line interventionists. For the moderates who wanted to avoid blowback, the program offered them influence on the ground without needing to announce yet another regime-change war or put U.S. personnel in direct combat.

For the hardliners who wanted a decisive regime change, the program helped the U.S. connect with groups who would become the leaders of Syria after Assad’s overthrow in December 2024, and also build the public case for U.S. intervention.

The final part in this series will look more closely at the administrative and civil society work that the Western consortium engaged in, the militant groups they worked with, and the sectarian violence and oppression that the consortium facilitated and covered up.

Mark Landler, “Obama Warns U.S. Faces Diffuse Terrorism Threats,” The New York Times, May 28, 2014. ↑

Chartwell Speakers, “Richard Barrett: Keynote Speaker,” Chartwell Speakers, accessed November 30, 2021. ↑

Several websites that the leaked internal UK FCO contractor documents in September 2020 were deposited in have been deleted over time, making it increasingly difficult for new researchers to access these files. As of July 2025, Copies of the original post can still be found on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine. For Part 1, see https://web.archive.org/web/20201128184446/https://freenet.space/read-blog/275_op-hmg-trojan-horse-from-integrity-initiative-to-covert-ops-around-the-globe-par.html. For Part 2, see https://web.archive.org/web/20201129163235/https://freenet.space/read-blog/276_op-hmg-trojan-horse-from-integrity-initiative-to-covert-ops-around-the-globe-par.html. These webpage captures offer links to the original files and users can preview the documents but the download link does not appear to work. The files on ufile.io appear to still be available for download but, in 2022, they were put behind a paywall. Readers should be able to download the entire archive using this link https://ufile.io/4vqv5h35. You may also contact the author at thomaba@bgsu.edu and request copies of documents.

ARK, “PART A – METHODOLOGY,” circa 2014e, Taming Syria II. Folder 023 GrassRoots ARK, https://ufile.io/kdf1gqxs, 1-3; ARK, “1.2.1 Methodology (untitled),” circa 2017b, Taming Syria I. Folder 017 MOR Resilience ARK, https://ufile.io/j11m22xe, 9. ↑

ARK, “2.1.5 Overall Approach and Methodology,” circa 2014a, Taming Syria I. Folder 006 AJACS ARK, https://ufile.io/wd5exmu4, 4-5. ↑

ARK, “ARK F.Z.C. 2.2.14,” circa 2014d, Taming Syria II. Folder 019 Acquisitions Framework ARK, https://ufile.io/5db2juq7, paragraph 1. ↑

ARK, “CPG 01737 1. Methodology,” 0-2. ↑

ARK, “CPG 01737 1. Methodology,” 0. ↑

ARK, “ARK F.Z.C. 2.2.5,” circa 2014b, Taming Syria II. Folder 019 Acquisitions Framework ARK, https://ufile.io/hhdnezl4, 1.; Ben Thomason, “Save the Children, Launch the Bombs: Propaganda Agents Behind The White Helmets (2016) Documentary and Media Imperialism in the Syrian Civil War,” The Projector 22, no. 2 (Summer 2022). ↑

ARK, “ARK F.Z.C. 2.2.5,” 1. See Appendix, Excerpt IX ↑

ARK, “ARK F.Z.C. 2.2.5,” 1. See Appendix, Excerpt IX ↑

ARK, “Part A: Methodology,” circa 2015, Taming Syria I. Folder 011 Syria Rapid Response ARK, https://ufile.io/c97tfzhv, 1. ↑

ARK, “ARK F.Z.C. 2.2.13,” circa 2014c, Taming Syria II. Folder 019 Acquisitions Framework ARK https://ufile.io/yckzx9a9, 1. ↑

ARK, “ARK F.Z.C. 2.2.13,” 1; ARK, “1.2.1 Methodology (untitled),” 6. ↑

ARK, “ARK F.Z.C. 2.2.13,” 1. ↑

ARK, “1.2.1 Methodology (untitled),” 2.; for corroborating reporting, see Ian Cobain et al., “How Britain Funds the ‘propaganda War’ against Isis in Syria,” The Guardian, May 3, 2016. ↑

ARK, “1.2.1 Methodology (untitled),” 5. ↑

Jad Melki and May Farah, “Syria Audience Research August 2014,” Research (Berlin: Media in Cooperation and Transition, August 2014), 5, 13. ↑

ARK, “1.2.1 Methodology (untitled),” 8. ↑

Melki and Farah, “Syria Audience Research,” 2, 4. ↑

Jad Melki, “Syria Audience Research 2016,” Research (Berlin: Media in Cooperation and Transition, 2016), 41-42. ↑

ARK, “1.2.1 Methodology (untitled),” 8. ↑

TGSN, “Sections 1.5-1.6 PROCESSES,” circa 2020, Taming Syria II. Folder 028 Other FCO Files, https://ufile.io/pgzo4kya, 4. ↑

Albany Associates, “Part A – Methodology,” circa 2017, Taming Syria I. Folder 016 MOR Resilience Albany, https://ufile.io/4ntc9ikt, 1, 6. ↑

Rima Marrouch, “Syria’s post-uprising media outlets: Challenges and opportunities in Syria,” Journalist Fellows’ Paper (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2014), 9, 23-24; Melki, “Syria Audience Research,” 33, 42-44, 78-79; Biljana Tatomir, Enrico de Angelis, and Maryia Sadouskaya-Komlach, “Syrian Independent Exile Media,” Briefing Paper (Copenhagen: International Media Support, November 2020), 34, 36-38. ↑

Steve Coll, “Assad’s War on Aleppo,” The New Yorker, August 28, 2016; The Syria Campaign, August 18, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/TheSyriaCampaign/photos/a.608812989210718.1073741828.607756062649744/1118057038286308/?type=3&theater. ↑

Brad Hoff, “The man behind the viral ‘boy in the ambulance’ image has brutal skeletons in his own closet,” The Canary, August 19, 2016. ↑

Ben Arthur Thomason, “The moderate rebel industry: Spaces of Western public–private civil society and propaganda warfare in the Syrian civil war,” Media, War & Conflict 17, no. 4 (2024): 567. ↑

ARK, “CPG 01737 Why ARK/Accadian?,” circa 2013b, Taming Syria II. Folder 027 StratCom MAO SMC FSA ARK, https://ufile.io/k8stc4d2, 1. ↑

Thomason, “Save the Children, Launch the Bombs.” ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Ben Arthur Thomason received his Ph.D. in American Culture Studies from Bowling Green State University in 2024.

He specializes in the history, culture, and geopolitical economy of U.S. imperialism and soft power. He has published peer-reviewed articles, including “Save the Children, Launch the Bombs: Propaganda Agents Behind The White Helmets (2016) Documentary and Media Imperialism in the Syrian Civil War,” in The Projector (2022), and “The Moderate Rebel Industry: Spaces of Western Public-Private Civil Society and Propaganda Warfare in the Syrian Civil War,” in Media, War and Conflict (2024).

He is currently seeking to publish his manuscript, Make Democracy Safe for Empire: US Democracy Promotion from the Cold War to the 21st Century.

Get in touch with Ben by going to benarthurthomason.com or by emailing him at benthomason696@gmail.com.

Lebanon is now in danger due to Russian betrayal. If the Chinese show any mercy, they will release a deadly virus into Syria, just as Fauci brought HIV into Libya with the help of a Palestinian doctor and Bulgarian nurses. He created the virus himself with the help of Dr. Robert Gallo from monkey and cat viruses.

Hezbollah and all of Lebanon are in danger because of Syria, and Russia is to blame. It’s not interesting how much Russia has changed since the deaths of Utkin and Prigozhin.

Lately I have not been following the news too much and was unaware of what was happening in Syria. Today I noticed that the Druze community that initially celebrated the fall of the evil dictator Assad who is a good friend of evil dictator Putin are now being mistreated as shown in this article.

https://thecjn.ca/news/canadian-druze-call-on-the-international-community-to-intervene-after-syrian-attacks/

If China protected Lebanon with a deadly virus or Israel procured something like Fauci and Trump procured in Wuhan and released it into that same Wuhan. Then would the Israelis protect the Druze and dump the infected rats on Damascus? Criminal genocidal Syria would deserve Israel to clean up Damascus and for Damascus to become part of Israel.

I mean something that the criminal and incompetent HTS would notice much later than Gaddafi noticed, that it would be too late and after six months Syria would have an Australian population density. Wouldn’t it be nice if Gaddafi’s HIV affair were repeated, when Gallo and Fauci wanted to kill Libyans and made HIV from cat and monkey viruses? Was Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor ended up in Libyan prisons because Fauci?

It will be a wonderful day when the candle burns for Jolani’s main supporters Dump and Putler.

Or would it be better if a disease broke out in Damascus that killed all of HTS and then Damascus would be part of Israel? Something so terrible that even the Taliban would repent and be scared and let girls go to school.

When Dump and Putler go to hell, someone will come along who will enable the Kurds and Druze to form a normal Syrian government together and put Jolani in prison like El Sisi put Morsi in prison.

I hope you understand that Jesus will hand over Trump and Putin to Lucifer because they support the criminal Jolani. I am convinced that Australia and France are more likely than Trump’s criminal USA to help the SDF.

The SDF would be better leaders of Syria than HTS. You can all be sure of that.