[This is the fourth part of a series on Syria and the effects of CIA intervention there, tied for the one year anniversary of the Syrian “revolution.” See Part I, Part II, and Part III.—Editors]

How do you sell the idea of a moderate rebellion without alienating the extremists who will do the actual fighting?

When foreign powers started supporting armed groups to overthrow the Ba’athist government in Syria after 2011, they were unsure about who could, or should, take Damascus.

Even within the leadership of the Obama administration, some figures, such as President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden, were skeptical that intervention would not descend into another unpopular regional boondoggle while others, such as Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, pushed for a hardline stance to back those groups whom she called “the hard men with the guns.”

It was a sensitive situation, especially because the main armed actors quickly revealed themselves to be Sunni sectarian theocrats aligned with groups such as al-Qaeda and the Muslim Brotherhood.

The U.S. and Salafi militants in the late Global War on Terror

Since September 11, 2001, the U.S. had ostensibly been at war with al-Qaeda and the violent internationalist fanaticism that, according to the U.S. government, it represented and spread across the world.

The Americans were still directly engaged in combat against al-Qaeda and their allied group, the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), in 2011 when the civil war in Syria, which borders Iraq, broke out.

The U.S. justified intervention abroad for the first decade of the 21st century under a narrative of fighting the Global War on Terror, specifically against the Sunni Arab variety of terror represented by al-Qaeda which was blamed for the attacks of 9/11.

Yet the situation in Syria, like Libya, offered another chance for the U.S. to go back to its traditional policy of empowering religious reactionaries in Muslim-majority countries to fight America’s secular nationalist and socialist enemies.

The U.S. and Western powers entered a tense relationship with the anti-Assad militant groups as the Syrian War progressed. The U.S. and its allies would quietly supply hard- and soft-power support and, in return, the militant groups would fight the Syrian government, renounce attacks on the Western powers, including Israel, and work with the Western powers to shape their international public relations.

According to internal documents from government contractors working on covert Western soft-power programs in Syria during the 2010s, Western governments were willing to work with theocratic and sectarian militias fighting the Ba’athist government up to, but excluding, the Islamic State, which later became known as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

ISIS’s predecessor, ISI, had for years fought a bitter sectarian struggle against the U.S. and Shia Muslims in Iraq, and ISIS was both unwilling to give up its war against the U.S.-backed Iraqi government and refused to adapt itself to Western public relations demands or renounce attacks on the West itself.

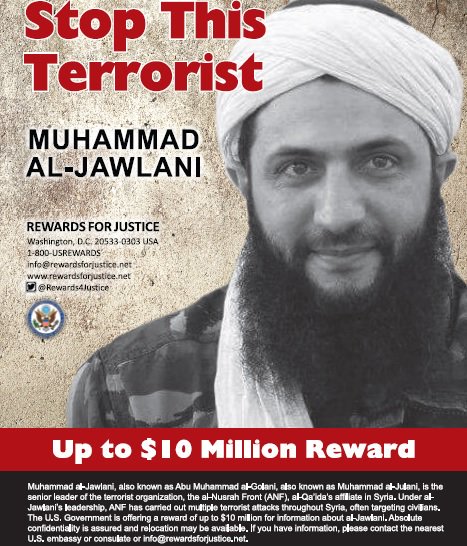

On the other hand, Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian al-Qaeda branch that grew out of ISI, and its leader, the now-current president of Syria, Ahmed al-Sharaa (nom de guerre Abu Mohammad al-Julani), was more pragmatic and pliable.

Nusra and Sharaa maintained a brutal sectarian theocratic vision for Syria internally, particularly against the Shia, but they avoided attacks on the West and Israel, distanced themselves from the Islamic State and international Jihadism, and showed flexibility in working with Western powers and their allies.

By 2017, they had distanced themselves publicly from al-Qaeda and rebranded themselves as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

Sunni sectarian allies of the West in the Syrian Civil War

The U.S. and its Western allies from 2012 onward claimed they would only support “moderate” armed groups in Syria. Western powers defined “moderate” as groups with a non-sectarian, liberal democratic vision for a future Syria, but in practice the groups they supported often failed to meet even these low standards.

Militias that received aid included violently sectarian, theocratic, and anti-democratic Salafi organizations: Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zenki, Ahrar al-Sham, and Jaysh al-Islam. Al-Zenki was promoted as a member of the moderate opposition that was vetted directly by the CIA and received BGM TOW anti-tank missiles.

Yet, by 2015, the public relationship with Zenki had to end after journalists and human rights groups released reports of atrocities committed by Zenki associates.

Ahrar al-Sham, which earned the nickname the “Syrian Taliban,” committed sectarian atrocities against Alawite civilians in Latakia in 2013 when its fighters entered the province, and they kidnapped hundreds of civilians from 2012 to 2016.[1]

Jaysh al-Islam became infamous for its 2013-2018 administration of Eastern Ghouta, regularly using arbitrary imprisonment and torture of civilians, and putting Alawites in cages to be used as roving human shields.[2] All three groups had, at various times from 2013 onward, been allies or enemies of each other as well as al-Nusra/HTS, and all three groups received covert media, public relations, and civil society assistance from UK government-funded contractors.

![Many locals have objected to putting female prisoners in cages, according to a local journalist [Al Jazeera]](https://covertactionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/many-locals-have-objected-to-putting-female-prison.jpeg)

Coyly courting al-Qaeda and friends

The Western powers, specifically the U.S. and UK, developed an ambiguous relationship with al-Sharaa and Nusra/HTS that reflected splits within Western governments and the tense history between the West, Sharaa, and the ideas and groups Sharaa represented.

Sharaa and his al-Nusra Front (later HTS) had been a major armed faction fighting for the overthrow of the Ba’athist government in Syria before the rise of ISIS, and became the dominant rebel organization after ISIS’s decline.

Nusra led a coalition of other Sunni theocratic groups in taking full possession of Idlib City from the Syrian government in April 2015, a great achievement in a war where the rebels time and again failed to conquer and hold major cities.

After the Syrian government took back complete control of Aleppo City at the end of 2016, government forces increasingly concentrated armed rebels and anyone associated with them into Idlib Governorate through a combination of conquests and transfer agreements in other parts of rebel-held Syria.

This created a sort of Jihadi Jurassic Park made up of various sects of Sunni theocratic armed groups (including many foreign fighters) but dominated by Sharaa and his allies. Idlib Governorate, thus, became the place where the armed rebels maintained the most authority for the longest time.

It also became the place where the Western powers had the most time and space to implement their pro-rebel soft-power programs. Leaked UK government documents show that, between at least 2014 and 2017, the UK government directed its contractors in Syria to explicitly and directly oppose ISIS, but to only implicitly and “indirectly” oppose al-Nusra and later HTS.

One UK “statement of requirement” for their contractors working to support Syrian civilian and rebel media from 2017 states that the overall objective of the project was to “contribute towards positive attitudinal and behavioural [British spelling] change” by “promoting and reinforcing moderate values in Syria.”

They would do this through supporting the approved so-called moderate armed opposition as well as so-called moderate civilian opposition government, security, civil society, and service providers. The document then states that, “Indirectly, these activities should support the rejection of extremist alternative narratives through bolstering the moderate alternative.”[3]

One 2014 Statement of Requirements document from the UK government for its contractors providing media and civil society support to the Syrian opposition specifically states that one of the tasks for the project is to “Counter violent extremist narratives by promoting the MAO [Moderate Armed Opposition] as a credible alternative.” There is a footnote given in that line which states that they would counter “ISIL/IS explicitly and ANF [al-Nusra Front] indirectly.”[4]

The UK government defined “moderate values” simply as “those that call for inclusive, non-sectarian, human rights adherent solutions” to problems.[5]

But what did it mean to “indirectly” counter violent extremists such as al-Nusra? The UK government documents do not provide a clear answer, but the policy can be inferred. In practice it meant promoting an idealized image of groups that the UK and its allies supported, while not openly antagonizing extremist, sectarian and theocratic groups so long as they were not affiliated with ISIS.

These policies created a large gray zone between the explicitly condemned ISIS and the publicly supported so-called moderate rebels. Al-Nusra/HTS operated, and ultimately took over Syria, from within that gray zone.

The Western soft-power consortium realized that many of the armed groups they supported could not consistently meet the “moderate values” as the UK defined them, and they developed clear protocols to relocate operations and cut ties if any partner groups threatened UK interests by, for example, defecting to ISIS.

Consortium partner and UK-government contractor Albany Associates stated in one document that it had developed media skills and strategy for Ahrar al-Sham and Jaysh al-Islam, two groups notorious for their sectarian religious extremism.

Yet Albany Associates assured its funders that its methods would avoid tying them to “groups who may or may not be at any given time viable, effective, respected in the community, or, in fact, moderate.”[6]

Idlib City “liberated” by Syrian al-Qaeda and Taliban

When Nusra and its allies took over Idlib City in late March and early April of 2015, UK government contractor Analysis Research Knowledge (ARK) described it in their internal documents as Idlib’s “liberation.” As the Salafi forces took control of Idlib City, ARK and its partners in media and civil society were among the first on the ground to help establish order as well as provide a narrative to understand the developments for Western governments and news outlets which otherwise had little access to Idlib.

The UK government had to request that ARK provide an overview of the situation, and ARK “mobilised its stringers and networks in civil society organisations, the Idlib Free Police, the Syria Civil Defence, and the political opposition to produce a rapid three-page analytical report and a verbal briefing.”[7]

This analytical report is not publicly available, but ARK’s description of the conquest in its internal documents as the “liberation” of Idlib, as well as its later reports about Idlib indicate that it viewed the Salafi takeover of the city as, if not a positive development, at least a situation it could work with.

Al-Nusra in 2015 conquered Idlib alongside fellow Sunni Islamist militias, namely Ahrar al-Sham.[8] Some influential Western voices searched for ways to benefit from the developments in Idlib.

The Washington Post allowed Ahrar al-Sham’s head of foreign relations to publish an opinion piece whitewashing the group as moderate revolutionaries in July 2015.

The presence of UK public relations contractors in Idlib City and the documentation showing their support for Ahrar al-Sham indicates that Western covert soft-power support had a role in crafting that narrative and giving Ahrar al-Sham a platform to promote it in The Washington Post.[9]

In August 2015 former CIA Director Petraeus suggested that the U.S. should split away “moderate” al-Nusra fighters from al-Qaeda to fight ISIS and Assad.[10]

Al-Nusra leader Ahmed al-Sharaa proved to be responsive to this vision, distancing his organization from al-Qaeda and rebranding its name and symbols, first in 2016 and then in 2017.

Maintaining a moderate rebellion without alienating al-Qaeda

ARK and its consortium partners continued, and in fact expanded, their operations in Idlib following the Salafi conquest. By 2017, large collections of Sunni rebels from various parts of Syria were losing their territories and being concentrated in Idlib.

Ahmed al-Sharaa (aka Abu Mohammad al-Julani) rebranded al-Nusra as Jabhat Fatah al-Sham in July 2016 and dropped its explicit al-Qaeda affiliation. At the same time Sharaa’s group sought to distance itself from al-Qaeda, it acted to consolidate control over Idlib and the other Sunni rebels.

On January 20, 2017, Sharaa and his allies fought a brief war with Ahrar al-Sham and its allies.

On January 28, Sharaa joined with several other Islamist groups which had concentrated in Idlib, including a large faction of Ahrar al-Sham, to form Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

HTS emerged victorious by July 23, 2017, taking complete control of Idlib City and about 60% of Idlib Governorate.[11]

This timeline is noteworthy because, in an internal document from either late August or early September 2017, ARK explained that it ran the communications strategy for Idlib City Council (ICC), doubling its Facebook following and increasing average views for videos from 3,000 to 60,000 in one month.

This was between June and July, 2017, just as HTS was taking complete control of the city.[12]

Idlib City Council operated under the administration of Jaish al-Fatah, the Salafi coalition led by Ahrar al-Sham and al-Nusra, later HTS, that had controlled Idlib City since April 2015.[13]

On August 15, according to Western-backed Syrian reporters, the Idlib City Council called for the formation of a “Salvation Government.” Shortly thereafter, on August 20, the council refused a demand that they hand over civil institutions to HTS and, on August 28, HTS seized Idlib City Council and confiscated much of the local assets that had been provided by foreign powers.[14]

HTS organized a Syrian General Conference and, on September 11, 2017, the conference delegates agreed to form a new government based on Islamic law. In November 2017 HTS declared the establishment of the Syrian Salvation Government, the regime that Sharaa would lead in Idlib until HTS took over Damascus in December 2024.[15]

ARK did not mention relocating during the inter-rebel war, or anything about rebel in-fighting at the time.

The fact that these contractors had clear protocols to shut down programs at the time and relocate in risky environments like Idlib indicate that they viewed the HTS takeover as something they could work with.

The CIA and other Western backers did freeze funding to Idlib during the rebel in-fighting out of concern that their support might go to un-approved opposition forces.[16] ARK merely states there had been a “recent shrinking” of the Free Syrian Army’s “overt presence” in Idlib at the time.[17]

By 2017, what was left of the Free Syrian Army had reconfigured into the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army. Also by 2017, the covert Western soft-power consortium began to support Ahrar al-Sham and Jaysh al-Islam, two major Salafi groups that would officially join the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army by 2018.[18]

This implies that, while the money streams lasted, ARK and its partners kept making moderate rebel propaganda regardless of who was in charge of the area.

Consortium partners claimed to promote only moderate factions, but “moderate opposition” was a nebulous concept that they defined and shifted as needed. Even if a truly moderate opposition had no real power on the ground, the idea of a moderate opposition could be kept alive as long as international entities had media production capabilities and paid collaborators communicating the right messages.

Without saying explicitly, internal UK documents show the failure of Western powers to establish a strong-armed opposition with liberal democratic values. For example, the UK tasked its contractors with promoting “gender sensitivity” and women’s empowerment in Syria.

This policy was not based on struggles for women’s rights native to Syria or informed by Syrian perspectives. Instead, it was “Her Majesty’s Government’s” ideas of women’s rights and gender sensitivity that were to be imported into Syria. However, this neo-colonial conception of promoting feminism had to be secondary to the main goals of fighting Assad, especially since the Western powers insisted on working with Salafi organizations with extremely patriarchal beliefs.

Describing the southern front of armed opposition supported by the UK and its partners, ARK noted “a requirement to promote democratic values and the participation of women and minorities to counter prevailing attitudes that have become extremist in all but name.”[19] Yet just as ARK would not directly oppose al-Nusra or HTS, it also would not directly challenge those attitudes. Instead, they wrote that

“The consortium is extremely aware of the risks of promoting women’s participation beyond currently accepted social norms in Syria, given the potential to hinder message resonance or result in a backlash against female participation. The proposed project will therefore continue to subtly reframe the narrative of women, by highlighting their work and its value, and increasing the amount of coverage of their initiatives and opinions as the context allows.”[20]

The consortium could maintain services as long as it did not offend local militias, so-called extremist or otherwise, and the services also became propaganda for both local and international audiences. Service providers such as the White Helmets and other Western-supported groups included women in their membership, and women featured prominently in photos and videos they released. They turned services featuring women into media that would then be promoted in the West by groups like The Syria Campaign.[21]

These reports would be passed along to Western journalists such as Simon Tisdall who, despite never seeing these spaces and services, reported that moderate and “informal” civil initiatives offered paths to democratic solutions if only Western politicians, donors and NGOs invested in them.[22] The system could have worked. It made the opposition look like a good investment for the West because they would fight the West’s enemies while promoting so-called Western values, while simultaneously promoting women’s rights among the Syrian opposition themselves because it would attract more Western support.

By their own admission in their internal documents, however, ARK and other foreign covert soft-power players showed that the West and their so-called moderate opposition was too weak to directly criticize the former affiliate of al-Qaeda, promote women’s equality, or safely bring Western journalists to Idlib.

Despite this reality on the ground, Western NGO reports and news articles could invent a different, if transient, reality where Idlib civil society appeared to be a dynamic and empowering place for women and moderate Syrians that international donors should support.

While Western pundits spun tales of a moderate opposition that was ever growing yet never triumphant, HTS built its Sunni sectarian state that would take over the majority of Syria in December 2024. The consortium created a gray physical and media space where it was difficult to separate indirectly opposing from indirectly supporting HTS through the foreign maintenance of a “moderate” opposition that operated largely at the sufferance, and ultimately for the benefit, of HTS.

Geopolitics Trump Values

Syrian rebel factions were pulled in different directions by different constituencies, foreign and domestic. Significant portions of the anti-Assad Syrian population did favor some kind of Sunni religious state similar to what the Islamist militias preached, and sectarian feelings against Alawites and other minorities were popular in some areas as well. Foreign backers from the monarchies of the Gulf Cooperation Council and other Sunni-majority countries, who wanted to promote Sunni-Islamist power, also represented an important constituency for anti-Assad rebels.

On the other hand, many Syrians grew resentful toward militias who refused to respect local customs and communities because they did not align with some puritanical version of Sunni Sharia, especially if those militias included a lot of foreign fighters.

At the same time, Western powers offered a lot of money, weapons and other technology to win the war, and the U.S. was the only power that could easily intervene and win the war unilaterally. Yet, the West was often a fickle and unreliable partner.

Powers like the U.S. and UK were willing to work with Sunni Islamists in many instances but were not committed to, and to an extent were alienated from, a Sunni Islamist project, especially if it might have ambitions outside of Syria which could threaten Western interests. Thus, from both domestic and foreign constituencies, Syrian rebel groups were pulled in conflicting directions: religious versus secular, nationalist versus internationalist, revolutionary versus reformist, and pragmatic versus ideological.

The Western powers tried to influence the conflict with billions of dollars of hard- and soft-power investments, both covert and overt. They did so to help the anti-Assad rebels fight the Syrian state, govern their territories, disseminate a distorted image of the rebels for local and international audiences to build support for the rebellion, and influence the rebels on the ground to make reality better fit that distorted image.

One can believe their insistence that they wanted to promote liberal democracy, women’s rights, and religious and ethnic pluralism. But the evidence suggests that, when faced with the choice, the U.S. and UK among other Western powers chose to prioritize making a Syria that would serve their geopolitical interests, or a weak and divided Syria that could not threaten their interests, over a Syria that represents their supposed values.

Ahmed al-Sharaa and his regime now in Damascus were influenced and strengthened by the Western interventions in the Syrian Civil War. The new government distanced itself from official al-Qaeda affiliation and international Jihadist ambitions thanks in part to the influences of the foreign powers but also to the Syrians themselves who failed to rally behind such a project.

It hardly represents the values of liberal democracy and social pluralism that Western powers claimed to be intervening for, yet Western powers such as the U.S., UK and European Union have embraced Sharaa nevertheless. It remains to be seen if Syria will consolidate as a strong and united state within the Western camp, remain a weak and divided country that cannot threaten outside interests, or become something more.

Guido Steinberg, “Ahrar al-Sham: The ‘Syrian Taliban,’” Comments (German Institute for International and Security Affairs, May 9, 2016), 1-3. ↑

Youmna al-Dimashqi, “Syrians Describe Horrific Torture In Jails Run By Islamist Militants,” HuffPost, March 25, 2016; MEE and Agencies, “Syrian rebel group appears to use Alawites in a cage as human shields,” Middle East Eye, November 2, 2015. ↑

UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, “STATEMENT OF REQUIREMENT SYRIAN MODERATE OPPOSITION RESILIENCE (MOR) STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS PROJECT,” July 2017,: Taming Syria I. Folder 015 MOR Resilience SOR, 2. ↑

UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, “STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS AND MEDIA OPERATIONS SUPPORT TO THE SYRIAN MODERATE ARMED OPPOSITION – STATEMENT OF REQUIREMENT,” November 2014: Taming Syria II. Folder 024 StratCom MAO SOR, 3. ↑

UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, “STATEMENT OF REQUIREMENT SYRIAN MODERATE OPPOSITION RESILIENCE (MOR) STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS PROJECT,” 2. ↑

Albany Associates, “Part A – Methodology,” circa 2017: Taming Syria I. Folder 016 MOR Resilience Albany, 4. ↑

“Part A: Methodology,” circa 2015: Taming Syria I. Folder 011 Syria Rapid Response ARK, 3. ↑

Anne Barnard, “Insurgents Seize Much of Key Syrian City,” The New York Times, March 28, 2015. ↑

Ben Arthur Thomason, “The moderate rebel industry: Spaces of Western public–private civil society and propaganda warfare in the Syrian civil war,” Media, War & Conflict, vol. 17, no. 4 (2024): 556–77; Al Nahhas, Labib, “Opinion – The Deadly Consequences of Mislabeling Syria’s Revolutionaries,” The Washington Post, July 10, 2015. ↑

Nancy A. Youssef and Shane Harris, “Petraeus: Use Al Qaeda to Fight ISIS,” The Daily Beast, August 31, 2015. ↑

“Hay’et Tahrir al-Sham take control of Syria’s Idlib,” Al Jazeera, July 23, 2017. ↑

ARK, “1.2.1 Methodology (untitled),” circa 2017: Taming Syria I. Folder 017 MOR Resilience ARK, 9. ↑

“The Last Hours Move… What Does the World Hold for Idlib?,” Enab Baladi, September 5, 2017. ↑

Noura Hourani and Avery Edelman, “After the Idlib City Council refuses to hand over administrative control, HTS takes it by force,” Syria Direct, August 29, 2017. ↑

“HTS-backed civil authority moves against rivals in latest power grab in northwest Syria,” Syria Direct, December 13, 2017; Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, Idlib and Its Environs: Narrowing Prospects for a Rebel Holdout, Policy Notes (The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2020), 1–18. ↑

Tom Perry, Suleiman Al-Khalidi and John Walcott, “Exclusive: CIA-backed aid for Syrian rebels frozen after Islamist attack – sources,” Reuters, February 21, 2017. ↑

ARK, “1.2.1 Methodology (untitled),” 10. ↑

Albany Associates, “Part A – Methodology,” 4. ↑

ARK, “1.2.1 Methodology (untitled),” 3. ↑

ARK, “1.3.3 Gender (untitled),” circa 2017: Taming Syria I. Folder 017 MOR Resilience ARK, paragraph 3. ↑

Peace Direct and The Syria Campaign, “Idlib Lives: The untold story of heroes” (The Syria Campaign, May 2018). ↑

Simon Tisdall, “Amid Syria’s horror, a new force emerges: the women of Idlib,” The Guardian, May 26, 2018. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Ben Arthur Thomason received his Ph.D. in American Culture Studies from Bowling Green State University in 2024.

He specializes in the history, culture, and geopolitical economy of U.S. imperialism and soft power. He has published peer-reviewed articles, including “Save the Children, Launch the Bombs: Propaganda Agents Behind The White Helmets (2016) Documentary and Media Imperialism in the Syrian Civil War,” in The Projector (2022), and “The Moderate Rebel Industry: Spaces of Western Public-Private Civil Society and Propaganda Warfare in the Syrian Civil War,” in Media, War and Conflict (2024).

He is currently seeking to publish his manuscript, Make Democracy Safe for Empire: US Democracy Promotion from the Cold War to the 21st Century.

Get in touch with Ben by going to benarthurthomason.com or by emailing him at benthomason696@gmail.com.