”It’s state terror / I’m gonna speak up / Maybe my time’s up / The world doesn’t accept trophies I’ve won in battle … / That’s why there’s hate in my words / Explain to a child why his hero is behind bars.”

— lyrics from “Anti O.R.U.A.M. Law,” by Oruam

Intro (Laws for Thee, Not Me)

Our cover image is a false-positive. A critical part of this story and the degree to which the criminalization of poverty and ideology of fear permeates Brazil, it will be addressed in the following sub-chapter.

To date, at least 12 capital cities across the South American giant, including state and federal representatives, have legislative proposals similar to the initial Anti-Oruam Bill tabled by São Paulo Councilwoman Amanda Vettorazzo. If approved, public funds earmarked for musicians and other artists who, allegedly, “incite organized crime or the use of drugs” will be prohibited.

Noted in Part I of this series, double standards and the possibility of Oruam targeted by Brazilian intelligence agencies while others regale in Brazil’s “belas-artes” scene, are qualified in the texts of authors like the late Rubem Fonseca.

With respect to his fans, editors and publishers, as well as panel judges who have showered praise and awards upon his collection of short stories, a cursory review of his literary work is tantamount to post-graduate studies in criminality.

Whether or not such stories—hereupon citing Cafetões (Pimps) as exhibit B—warrant censorship is, at best, an afterthought. However, in riveting detail, Pimps depicts an overly self-righteous policeman who, having jacked aside the balance scale between the law, his authority and fancy of an ideal society, particularly for women, executes a pimp in the presence of his prostitutes. “Look here, girls, I’m keeping a close eye on you, understand?” the officer threatens while demanding they hang up their trade in exchange for respectable employment. “If not, I will blow your brains out like this bitch.”

Cover Image Controversy

Until March 2018, I was, like most, unaware of the growing curiosity behind this report’s cover image. Online fuss was intense and rapidly increasing, so I took a peek. I came to find out that fake news was spreading like wildfire about Marielle Franco. Days earlier, the Rio de Janeiro councilwoman, born and raised in the Maré (favela) Complex, was assassinated and social media users took the tragedy to hurl injurious remarks about her.

In one instance, they chastised Marielle’s marriage to Marcinho VP—Oruam’s father, Márcio dos Santos Nepomuceno, was known by that nickname as a young man—and how she was elected to office by the Comando Vermelho (Red Command or CV). While Marcinho VP is alleged by Brazilian authorities to be a prominent leader of the gang, Brazilian media spares no coverage when given the chance to describe the group as “organized crime” involved in widespread drug-trafficking.

The defamation campaign centered around our lead photograph. Marielle Franco is not the young lady pictured. The young man is not Marcinho VP or anybody else with that nickname. If that weren’t enough, Marielle and Marcinho VP were never husband and wife. Nonetheless, these textbook false-positives ignited social media where Brazilian officials chimed in, fueling the flames of misinformation.

“Pregnant at 16, ex-wife of Marcinho VP, marijuana user, rival gang defender and elected to office by the Red Command,” decried Congressman Alberto Fraga about Marielle on his social media page.

“She will not be missed at all,” wrote Rio de Janeiro Justice Court Judge Marilia de Castro Neves. In a separate online post, Neves suggested how “Marielle was not only an ‘activist’ but was completely involved with criminals. She was elected to office by the Red Command and did not fulfill ‘obligations’ assumed by her supporters.”

After lengthy investigations, Neves was temporarily removed from the bench for a 90-day period last year (2024). “It is unacceptable that faced with fake news, a judge believes (s)he is sufficiently informed to express prejudiced and offensive opinions such as this judge,” said special rapporteur Alexandre Teixeira who oversaw the inquiry.

Permanent dismissal was not determined. However, crystal clear was Neves’s intent: Criminalize Marielle; sway public opinion; foment the errant belief that her assassination was related to the company she kept, what Professor Marcelo Lopes de Souza refers to in his book, Drugs and the “Urban Question.” In Brazil, diversion tactics take away accountability from the real businessmen responsible for drug importation, exportation, wholesale and money laundering.

Subjected to a similar playbook prompted by sensationalized media reports are the favelas, Marcinho VP and, more recently, Oruam, a spectrum raising the question not only of media and political persecution but coordinated intelligence operations against the trapper from the sprawling German (favela) Complex in Rio de Janeiro.

“My father and I have no photos together,” Oruam regreted. “He’s not present, physically, in my life and, as if that were not enough, the media try every chance they get to destroy what he means to me.”

CV

”My only concern is that you don’t oppress me / …With faith in God, I’m CV until I die.”

— lyrics from “Faith in God,” by MC Duduzinho

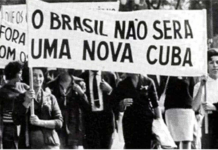

Unlike the Pink Tide, the Red Command is rarely if ever discussed in relation to resistance to neo-imperialism, albeit beaming from within Brazil. Whereas the country’s notorious military police passed go without a hitch from its founding days during the junta (1964-1985) and stands firm to this day, the CV was not as much invited to Brazil’s National Truth Commission to explain the reason for its establishment and why it persists.

Instituted during former President Dilma Rousseff’s administration and tasked with investigating human rights abuses between 1946 and 1988, the former head of state stressed that the country needs to know the totality of its history. “The new generation deserves the truth,” she said during the commission’s opening ceremony.

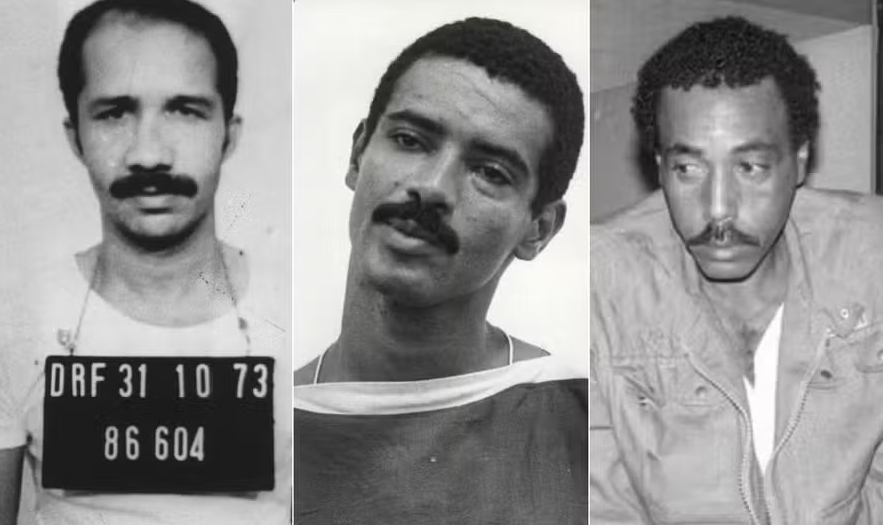

Founded in 1979 by Rogério Lemgruber, William da Silva Lima and José Carlos dos Reis Encina at Cândido Mendes Penitentiary—“Cauldron of Hell”—(Ilha Grande, Rio de Janeiro), “Peace, Justice and Liberty” comprised the CV’s flagship slogan. Establishing order and protection from guards were their initial objectives, goals achieved that garnered respect from other prisoners and even some prison officials. More pedantic in tracing their roots, popular historians cite earlier dates as the CV’s origin when the group was initially called the Red Phalanx or nameless.

Rio de Janeiro Councilwoman Talita Galhardo, along with co-authoring Councilman Pedro Duarte, have tabled an Anti-Oruam bill for debate. She cites Oruam at a live performance reciting the lyrics to “Gaza Strip” (by MC Orelha) as proof of his alleged incitement of organized crime.

Part of the song’s chorus includes “Red Command RL,” the acronym referencing Rogério Lemgruber. Raised in the Rebu favela, Lemgruber and his brother, Sebastião Lemgruber, were charged with multiple bank robberies before the former went on to co-found the CV.

Upholding their cause for “liberty,” the CV planned and carried out prison escapes. Once free, some CV cells “expropriated” banks and armored trucks, the exploits of which were dedicated to fulfill two of their Ten Commandments: (7) Act collectively, and (8) Strengthen those less fortunate. In practical terms, this meant opening a “caixa” (savings account), monies used to support remaining incarcerated members and their families, finance future prison breaks and invest hard cash into their communities.

Outlawed in 1964 by the military dictatorship, the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB) has long disarmed after regaining its legal status in 1985. Groups like the National Liberation Command (COLINA) and Palmares Revolutionary Armed Vanguard (VAR-Palmares), both entities active in armed struggle against the junta, even counting Dilma Rousseff in their ranks in her early twenties, no longer exist.

Ultimately, the last active armed resistance group that emerged in opposition to Brazil’s fascist regime and prior systemic oppression accentuated by military rule is the CV.

Despite his father’s notoriety, describing himself as having been just another CV “soldier,” Oruam has publicly denied affiliation with the group or any other such entities. At a recent concert in Rio de Janeiro, he spit in the face of front row fans who were throwing up gang signs at him.

Makings of Marcinho VP

Born in 1970 in Vigário Geral favela (Rio de Janeiro), Márcio’s father was killed when he was a baby and his mother, Maria Auxiliadora Santos, a maid from Salvador, Bahia, was arrested on four different occasions in Rio de Janeiro. “After the death of my mother, I felt obliged to care for my siblings,” she said, “which led me to commit crimes to guarantee our sustenance.”

According to his autobiography, Marcinho VP: Truths and Positions—Penal Rights of the Enemy, he and his three siblings were raised by an aunt after the family relocated to São João do Meriti (Rio de Janeiro).

In 1993, a death squad composed of 36 armed and hooded men, invaded Vigário Geral favela, killing 21 people. It was one of the largest massacres in Rio de Janeiro’s history until May 2021 when the police invaded Jacarezinho—one of Rio’s historic urban quilombos that transformed into a favela—leaving 27 residents and an officer dead.

“I really miss numerous friends who’ve passed / Day of tragedy with the stench of death,” Oruam, who was raised in the nearby German (favela) Complex, raps in Filho Do Dono (The Boss’s Son). “The state is genocidal with residents.”

Denying ever having been a drug-trafficker and other crimes charged against him, Marcinho VP admits to a past predilection for bank and armored truck heists where CV sympathizers working at those institutions first conducted intelligence-gathering operations.

Following one such incident, support helicopters hovered above a favela as police and special forces converged upon the community in search of the assailants.

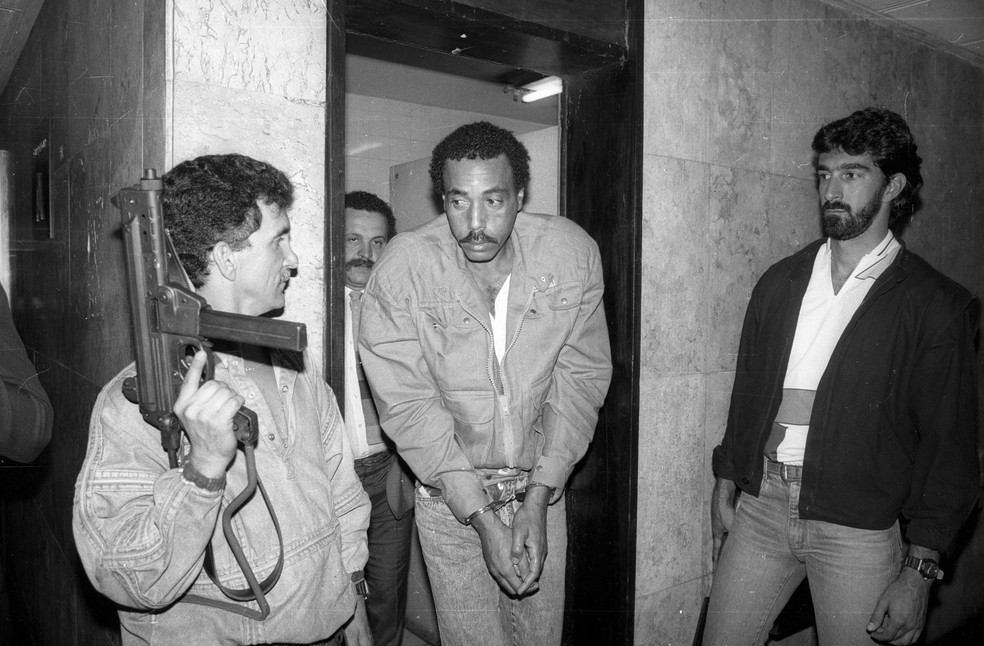

Marcinho VP recalls three comrades killed and officers recovering a duffle bag full of cash which disappeared from the scene, never to be recovered by investigators. He also claims to have been kidnapped by police officers before his detention in 1996 and released only after comrades robbed a bank and paid the ransom.

Sentence

Marcinho VP was apprehended in 1996 by undercover Rio de Janeiro police detectives operating in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul. Subsequently sentenced to 36 years in prison for several crimes, including his alleged involvement in organizing (while behind bars) the murder of Márcio Amaro de Oliveira, a CV leader of the Santa Marta (Dona Marta) hillside favela who bore the exact same nickname—Marcinho VP, as well as ordering (also while behind bars) the murder of two rival gang members, he has been transferred to several maximum security penitentiaries.

Currently, he is detained at the federal penitentiary in Catanduvas in Paraná state.

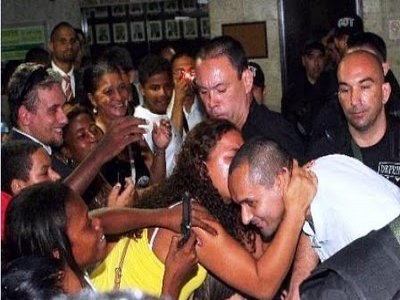

Brazilian criminal law restricts all convictions to a maximum of 30 years. Therefore, barring some bureaucratic shenanigans, next year should see Marcinho VP’s release. His return to civilian life is scheduled to occur amidst what is already shaping up to be a highly contested 2026 Brazilian presidential election. Up for debate will be issues concerning security, gangs and, most likely, him.

Over the past months, Oruam has started to play a more public role in advocating for his father’s release. “My father made a mistake but he’s paying for it and more,” he said in 2024 during a live performance. “I just want him to complete his sentence with dignity and be released with his head held high.”

Defense

A “political prisoner” is what Marcinho VP’s lead defense attorney, Flávia Fróes, calls him. As for the CV and similar groups, she explains that “gangs emerged to resist oppression” and have “organized as a means to combat excessive state violence.”

True to form, Brazilian media dub Fróes the “drug-traffickers’ lawyer,” precisely for her staunch legal representation of clients from marginalized territories and impoverished backgrounds. Defendants include high-profile “anti-repression group” leaders from vying factions, even Little Seaside Fernando (Luiz Fernando da Costa, aka Fernandinho Beira-Mar), a former CV leader based in Rio de Janeiro who was eventually detained by Colombian authorities in a FARC encampment in 2001.

“Survival solidarity networks created during slavery in Rio de Janeiro exist to this day,” Fróes emphasizes in rebuttal to the press’s assertion that favela residents protect drug-traffickers. “It is difficult for somebody outside of those communities to understand how the mentality of someone who lives there works. The police and state only show up armed and shooting…Even if you kick a dog it bites.”

Despite denials by the legal defense team of Rio de Janeiro’s ex-mayor and former governor Sérgio Cabral Filho, Marcinho VP swears that he personally met the disgraced politician during a pagode concert in the German (favela) Complex. Moreover, he says CV operatives helped Cabral Filho in his victorious bid for city hall in 1996. “From my standing in the community, he was allowed to speak, tell his stories,” Marcinho VP assured, “and, ultimately, dupe me wholesale.”

More on this contested relationship in Part III of “Republic of Oruam.” We will also look at why Fróes, an attorney who openly admits to her past “fascist” beliefs, arraigns Brazil’s progressive political leadership class for its devastating “ambidextrous” policies and how such measures situate folks like Oruam, his father and favelados (local favela residents) outside right/left ideological strands.

Postscript

”This crap society doesn’t respect us / So cross our borders and you’ll pay a price.”

— lyrics from “Faith in God,” by MC Duduzinho

No wildcard at play, the CV emerges from severe, systemic economic exploitation. A prime example is the more than $19 billion (USD) annual wage theft from the largest demographic in Brazil, detailed in the Salary Loss From Racial Inequality report (2024). The recent corruption scandal involving public servants swindling pensioners and seniors out of more than one billion (USD), resulting in the resignation of Brazil’s Minister of Social Services, Carlos Lupi, is the latest demonstration. And I have yet to touch on Brazilian police brutality.

Brazil “deserves the truth” and that “never, ever again should one’s history exist without a voice,” said Dilma at the outset of the National Truth Commission. “Those who give voice to that history are…unafraid to write it.”

Paradoxically, the commission’s three-volume, 3,388-page, final report, while it acknowledges repressive state apparatuses that gave and give way to human rights abuses, mentions the word “favela” just six times. So the soundtrack to this crucible is played by Marcinho’s son, Oruam, as well as Mc Poze do Rodo, Sabotage, Racionais MC’s and others.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

A former editor-at-large for African Stream and ex-staff writer at Telesur, Julian Cola is publishing a memoir of intimate, community-inspired stories titled “Proibidão (Big Prohibited): Off-Grid Correspondence From Brazil & Ecuador.”

The pre-launch is in December 2025. It includes media beefs and, having taught in the teaching-English-industrial-complex, the book discusses linguistic soft-power in the region and creative ways of dealing with it as mentioned in the essay, Listening To 2Pac In The Andes (Kawsachun News).

For more information contact: traducoessemfronteiras@protonmail.com