[This is the second of two CAM special articles this week in honor of Indigenous Peoples Day.–Editors]

In August 2023, the Kaw Nation transported a sacred boulder, known as Iⁿ‘zhúje ‘Waxóbe, from Lawrence, Kansas, to ancestral Kaw land near Locust Grove, Kansas, where Kaw Nation members lived.

The Lawrence City Council voted 5-0 to allow for the transfer of the boulder which, since 1929, had been located in a traffic thoroughfare near the Lawrence city center with a plaque honoring the pioneer settlers of Kansas.[1]

Millions of years ago, Iⁿ‘zhúje ‘Waxóbe had been deposited by a glacier along the banks of the Kaw River at the mouth of Shunganunga Creek.

The sacred boulder served thereafter as a spiritual anchor for the Kaw Nation.

The removal of the boulder from the Kaw River and appropriation of it by white settlers who stole the Kaw’s land and forced their removal to Oklahoma, was an insult to the Kaw people.

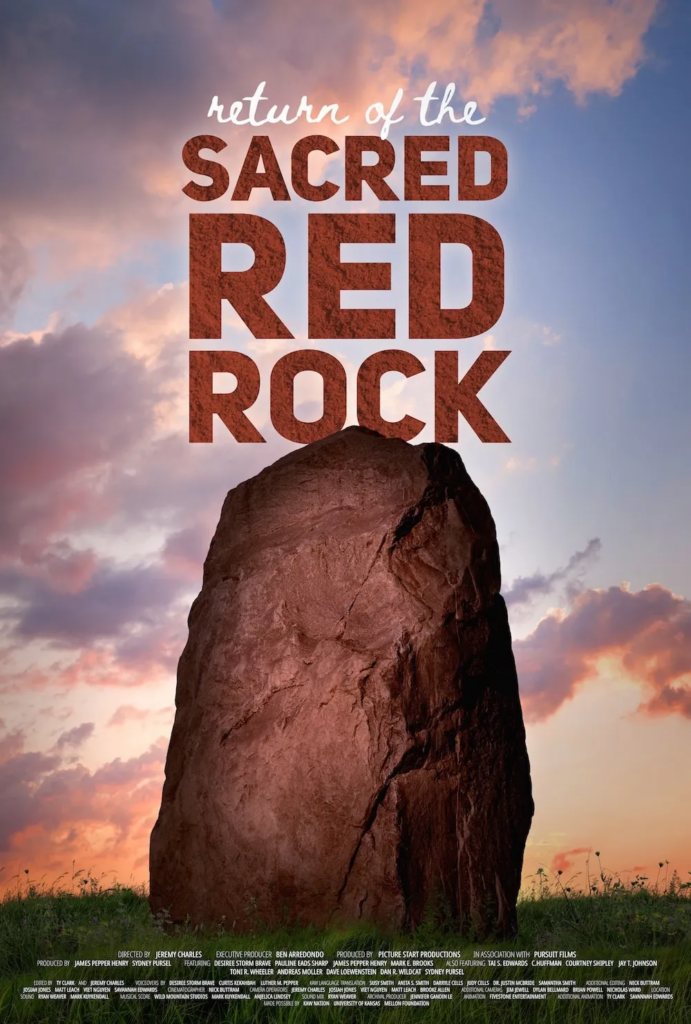

The story of Iⁿ‘zhúje ‘Waxóbe and the Kaw Nation is told in a new documentary entitled The Return of Sacred Rock, which which first screened in Lawrence, Kansas, in late May and can be seen at AlterNative Film fest in Wichita on 11/7 and University of Kansas on 11/8.

Featuring historical footage mixed with interviews of members of the Kaw Nation, The Return of the Sacred Rock is produced by Ben Arredondo, who also produced 31 media projects for the First Americans museum, and is directed by Jeremy Charles, a Cherokee filmmaker living in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The film provides a fascinating history of the state of Kansas that is little known to the public.

The Kaw people who originally inhabited the state of Kansas and gave the state its name are more formally known as Kaáⁿze.

Considered the “people of the south wind,” the Kaáⁿze were known as protectors who were cousins of the Osage, Quapaw, Omaha and Ponca tribes and hunted bison on the Kansas plains.

A member of the community said in the film that the Kaáⁿze people had a lot of land to hunt on and were happy living in modern-day Kansas until the white settlers came.

Kansas likes to think of itself as a progressive state that was settled in the 19th century by New England abolitionists.

The New Englanders and other settlers, however, coveted the Kaáⁿze’s land and benefited from its purchase by the local government for a mere nine cents an acre.

In 1844, the Kaáⁿze became desperate because of huge floods that took a toll on the Kaáⁿze’s ability to grow food crops. The Kaáⁿze people were starving and so were willing to agree to selling off their land for revenue that could be used to purchase food.

At the time, many of the settlers had disparaging views of the Kaáⁿze. They believed that the Kaáⁿze could not take care of their children or grow bountiful crops, though before the flood, they had an abundance of corn, which they distributed to other Native tribes.

One member of the Kaáⁿze Nation said that, while technically the white settlers “did not steal the land, they came awfully close.” The Kaáⁿze were left homeless, forced to live along the Neosho River where they foraged for food.

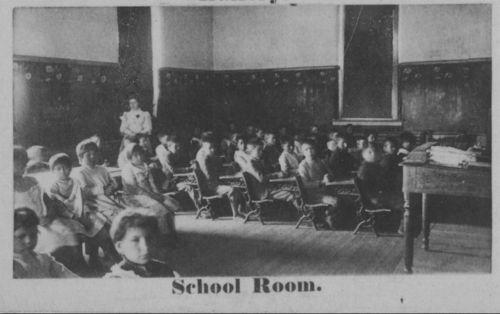

As they tried to set up new villages, Kaáⁿze boys were forced to attend a government school—the Haskell school—where they had their hair cut and were deprived instruction in the Kaáⁿze language and culture.

The goal of the Haskell School was to have the Kaáⁿze assimilated into American life, though many of the Kaáⁿze boys were forced to work on local area farms where they were used as slave labor.

In the 1870s, the Kaw reservation near Council Grove shrank from 80,000 to 25,000 acres. The Kaáⁿze chiefs were powerless to stop the land theft as Kaáⁿze were pushed off the reservation.

The Kaáⁿze’s game was wiped out and they could no longer survive hunting bison. Women were left wailing as they had to leave everything behind, including the bones of their ancestors.

Suffering from malnutrition, many Kaáⁿze died from smallpox, typhoid and measles. The population was reduced from 20,000 tribal members to only about 194.

Amazingly, in 1873, two weeks before their forced displacement, the Kaáⁿze gave gifts to the locals, even though they had been the ones to push them off their land and to try to destroy their culture.

One member of the Kaw Nation featured in the film said that this kind act “embodied who the Kaw were.” She said that her grandfather Elmer told her that “you give until it hurts” and that in turn “you will receive blessings.”

In 1929, residents in Lawrence, Kansas, got the railroad to help them remove the Iⁿ‘zhúje ‘Waxóbe from the river and put it in downtown. A dedication paid homage to the white settlers who officially founded the city of Lawrence after displacing the Kaw.

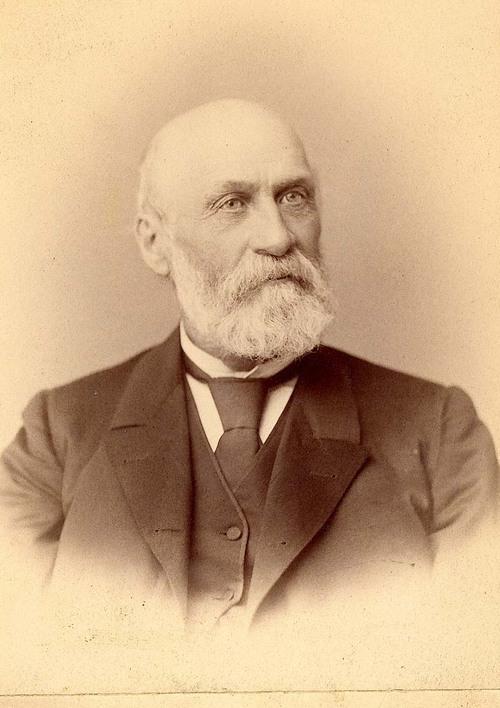

The park where the stone was placed was named after Dr. Charles Robinson, one of the most successful land speculators in early Kansas and the state’s first governor, whose name was put on the newly installed plaque.

Originally from New England, Dr. Robinson served from 1887 to 1889 as superintendent of the Haskell School, where native boys were cut off from their heritage and forced to perform slave labor.[2]

Members of the Kaw Nation said that the removal of the Iⁿ‘zhúje ‘Waxóbe sacred rock in 1929 was “a way to erase the natives from the memory of the land.” Iⁿ‘zhúje ‘Waxóbe was always sacred to the Kaw people and like the altar at a church.

People would gather at the stone and pray to Wakonda, the creator. Considered to be a miracle, the stone was said to embody the qualities of the creator and to have special powers. The Kaw and other Native groups believed that everything has a spirit, even the rocks.

For years, Lawrence would host a town festival named after Kaw chief Washinga, who froze to death following the mass expulsion of the Kaw people from their ancestral land. This history was unknown to most of Lawrence’s population.

The main high school in Lawrence named its sports teams the “Braves”—another insult to the Kaw people. At that school, students were never taught the history of the Kaáⁿze people, or about Washinga, the last Kaw chief.

When some members of the Kaw Nation tried to buy back some ancestral land, it brought back old prejudices and stereotypes. Some residents expressed fear that the Kaw would build a casino and bring crime to Lawrence.

Back in the mid-19th century, Lawrence town newspapers had referred to the Kaw as “dirty, thieving Indians,” which is not far removed from how they were presented again.

At the end of the film, members of the Kaw Nation emphasized the importance of the return of the sacred rock to their community and how this has inspired a revitalization of the Kaw language and traditions.

By returning the rock, they believe they have reclaimed their heritage and arre ready for a renaissance after surviving years of persecution and hardship.

- The Pawnee and Kaw (or Kanza) nations were long-term enemies with a history of conflict stemming from competition for resources like hunting grounds and, later, fur pelts. This long and often bloody war included events like a Pawnee attack on a Kanza village in retaliation for a Kanza massacre. Peace between the two was achieved around 1872.

The transfer of the rock was enabled by a $5 million grant to the Kaw Nation from the Mellon Foundation, which also helped finance production of Charles’s film. ↑

A graduate of Amherst College, Dr. Robinson graduated from the Berkshire Medical College in 1843 and served in the California State Assembly from 1851 to 1852 after going to California as part of the gold rush. A passionate abolitionist who fought political battles against pro-slavery advocates and was imprisoned with John Brown’s son, he was Kansas governor from 1861 to 1863 and served in the state senate from 1873 to 1881. Robinson was also a regent of the University of Kansas for 12 years. ↑

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Jeremy Kuzmarov holds a Ph.D. in American history from Brandeis University and has taught at numerous colleges across the United States. He is regularly sought out as an expert on U.S. history and politics for radio and TV programs and co-hosts a radio show on New York Public Radio and on Progressive Radio News Network called “Uncontrolled Opposition.”

He is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine and is the author of six books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019), The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018), Warmonger. How Clinton’s Malign Foreign Policy Launched the U.S. Trajectory From Bush II to Biden (Clarity Press, 2023); and with Dan Kovalik, Syria: Anatomy of Regime Change (Baraka Books, 2025).

Besides these books, Kuzmarov has published hundreds of articles and contributed to numerous edited volumes, including one in the prestigious Oxford History of Counterinsurgency .

He can be reached at jkuzmarov2@gmail.com and found on substack here.

Excellent article. The Pawnee and Kaw (or Kanza) nations were long-term enemies with a history of violent conflict stemming from competition for resources like hunting grounds and, later, fur pelts. This long and often bloody war included events like a Pawnee attack on a Kanza village in retaliation for a Kanza massacre. While US government attempts to broker peace were sometimes successful in the short term, the conflict continued until the Kanza and Pawnee finally made peace in 1872.