Winston Churchill’s enthusiasm for chemical weapons

Winston Churchill was a great fan of chemical weapons. His advocacy, which in this respect was refreshingly free of the cant and hypocrisy we have become used to, was longstanding. He thought such weapons were particularly suited to quelling rebellion in those parts of the British Empire where, for him at least, life was cheap.

In 1919, when the use of mustard gas in the First World War was still being discussed by the victors, he wrote a memorandum to the War Office, or what we call in these more enlightened time, the Ministry of Defence:

I do not understand this squeamishness about the use of gas. We have definitely adopted the position at the Peace Conference of arguing in favour of the retention of gas as a permanent method of warfare. It is sheer affectation to lacerate a man with the poisonous fragment of a bursting shell and to boggle at making his eyes water by means of lachrymatory gas.

I am strongly in favor of using poisoned gas against uncivilised tribes. The moral effect should be so good that the loss of life should be reduced to a minimum. It is not necessary to use only the most deadly gasses: gasses can be used which cause great inconvenience and would spread a lively terror and yet would leave no serious permanent effects on most of those affected.

Churchill was not alone in arguing that chemical weapons were a humane alterative. In the same period ‘the American Legion actually argued that poison gas was one of the most civilized weapons of warfare, a preferable alternative to explosives and bayonets.’

Churchill did not confine himself to advocating the use of gas to put down rebellions in the empire; he was also very keen to use it against the Bolsheviks in 1919. The chemical warfare research establishment at Porton Down – which hit the headlines again recently in respect of the Skripal poisonings just a few miles away – had just developed a new weapon called the ‘M Device’ which was an exploding shell (some describe it as a bomb) containing highly toxic gas. The general in charge enthused that it was ‘ the most effective chemical weapon ever devised’.

That article continues:

A staggering 50,000 M Devices were shipped to Russia: …. Bolshevik soldiers were seen fleeing in panic as the green chemical gas drifted towards them. Those caught in the cloud vomited blood, then collapsed unconscious.

But the weapons proved less effective than Churchill had hoped, partly because of the damp autumn weather. By September, the attacks were halted then stopped. Two weeks later the remaining weapons were dumped in the White Sea.

World wars and local wars: they just don’t kill enough people

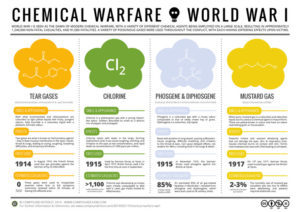

Although chemical weapons had gained great notoriety in the 1st World War gas was ultimately disappointing as a weapon and caused less than one percent of the total fatalities. The Wikipedia entry Chemical weapons in World War I gives numerous examples:

- The killing capacity of gas was limited, with about ninety thousand fatalities from a total of 1.3 million casualties caused by gas attacks. Gas was unlike most other weapons of the period because it was possible to develop countermeasures, such as gas masks. In the later stages of the war, as the use of gas increased, its overall effectiveness diminished.

- The first instance of large-scale use of gas as a weapon was on 31 January 1915, when Germany fired 18,000 artillery shells containing liquid xylyl bromide tear gas on Russian positions on the Rawka River, west of Warsaw during the Battle of Bolimov. Instead of vaporizing, the chemical froze and failed to have the desired effect.

- Chlorine was less effective as a weapon than the Germans had hoped, particularly as soon as simple countermeasures were introduced.

- The first use of gas by the British was at the Battle of Loos, 25 September 1915, but the attempt was a disaster. … the wind proved fickle, and the gas either lingered in no man’s land or, in places, blew back on the British trenches

- [Despite its fearsome reputation and the horrible burns its inflicted] Mustard gas [was] not an effective killing agent … The polluting nature of mustard gas meant that it was not always suitable for supporting an attack as the assaulting infantry would be exposed to the gas when they advanced.

The hysteria and self-interested patriotism of the media produced instances of macabre humour:

In Britain the Daily Mail newspaper encouraged women to manufacture cotton pads, and within one month a variety of pad respirators were available to British and French troops, along with motoring goggles to protect the eyes. The response was enormous and a million gas masks were produced in a day. The Mail’s design was useless when dry and caused suffocation when wet—the respirator was responsible for the deaths of scores of men.

Wikipedia concludes that although ‘chemical weapons were used in several, mainly colonial, [subsequent] wars where one side had an advantage in equipment over the other’, ‘by the end of the [1st World War] war, chemical weapons had lost much of their effectiveness against well trained and equipped troops.’

Wikipedia’s assessment is vindicated by the 2nd World War. White House spokesperson Sean Spicer was pilloried by the media back in April 2017 when he asserted that ‘President Bashar al-Assad of Syria was guilty of acts worse than Hitler’:

“We didn’t use chemical weapons in World War II,” Mr. Spicer said. “You know, you had someone as despicable as Hitler who didn’t even sink to using chemical weapons.”

Spicer was wrong about Assad, half wrong about the US, but right about Hitler, quite a good success rate for a White House spokesperson. Although the media, wallowing in sanctimoniousness, had a field day Spicer had a point, although he would not have realised that. Although the Nazis had used gas in the extermination camps, they had not used it on the battle field. Neither had the Soviet Union, nor Britain, despite Winston Churchill’s urging. Both the Soviet Union and Germany at different times with their back to the wall had compelling reasons to use chemical weapons, indeed any weapons that might offer relief. Some have suggested that Hitler’s personal experience of mustard gas in the 1stWorld War might have been a factor but that is not very credible. More to the point was fear of retaliation combined with low efficacy against a peer adversary who could take countermeasures. When the pros and cons were added up, the cons won the day.

Ironically the only casualties of chemical weapons in the European theatre (Japan had briefly used chemical weapons against China) were accidental and occurred when a US ship carrying mustard gas was bombed in Bari, in Italy, in 1943.

The major use of traditional chemical weapons in the postwar period has been by, and in, Iraq. Saddam Hussein used them against Iran with assistance from the United States, and against Kurdish rebels. The Iraq-Iran war ended in a stalemate and chemical weapons were shown to be of limited efficacy. A US Marine Corps study concluded that:

…we must not think of chemical weapons as “a poor man’s nuclear weapon”. While such weapons have great psychological potential, they are not killers or destroyers on a scale with nuclear or biological weapons.

Chemical weapons have various drawbacks even for victors. They can make land uninhabitable for generations – the Scottish island of Gruinard used to test anthrax in the 1940s is a case in point – and they can have long term health effects both not merely on victims but on administering troops as well. Agent Orange, the herbicide used by the US in Vietnam is the classic case of this with former US (and allied troops) suffering consequences decades later.

The self-serving definition of “chemical weapons”

But, by what we might consider a lawyer’s sleight of hand, Agent Orange is not classified as a chemical weapon in the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) administered by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, OPCW.

Much turns on definition. The US used three main chemical weapons in Vietnam, none of which attracted the condemnation of the OPCW: Agent Orange, CS Gas, and napalm. They provide a spectrum which illustrates the blurred line of definition, but which also exposes the artificiality of the chemical weapons debate:

Although the consequences of using herbicides like Agent Orange later became clear, they were always intended as nonlethal chemical weapons. The line was less clear with CS gas. Though it was officially intended to flush out tunnels, those caught inside were often asphyxiated, and even survivors suffered respiratory lesions.

And there was no blurring of lines when it came to napalm.

Napalm was, of course, seared on world conscience by the famous photo of the naked Vietnamese girl fleeing a napalm assault on her village in 1972.

But it is perhaps CS gas, a British invention (like VX) widely used throughout the world for protest control and crowd dispersion which illuminates the issue. A lethal chemical gas could have been used instead of CS, but did it make any real difference? Once flushed out the Vietnamese could be captured or shot.

The United States, despite its outrage at North Kore possessing a rudimentary nuclear deterrent remains the only country to have used nuclear weapons. Similarly, despite Nikki Haley’s expressions of outrage at (unproven and highly implausible allegations of chemical weapon use by the Syrian government) – ‘Only a monster does this’–the United States is arguably the greatest user of chemical weapons in history if we extend the definition beyond that expressed forbidden by the Chemical Weapons Convention.

That would include Agent Orange, CS gas on the battlefield, napalm, white phosphorous and depleted uranium, and perhaps others. America’s Vietnam war was dubbed ‘The Chemical War’ in the New York Times. (earlier the New York Herald Tribune headlined ‘Napalm the No. 1 Weapon in Korea’).

Ironically, given her special aversion to chemical weapons, Nikki Haley’s brother, Mitti, served in the US Chemical Corps.

The Military-Industrial complex: disdain for chemical warfare

From the point of view of the military-industrial complex chemical weapons in general have drawbacks. They are not sexy and exhilarating for taxpayers in the way that fighters, bombers and aircraft carriers are. Moreover, they tend to give war, and weapons, a bad name. But worst of all, they are cheap to produce – at a rough guess with a nerve agent such as sarin you could kill the world’s population a few times over for the cost of an F-35. So where’s the profit in that?

The twin problems with chemical weapons–efficacy and democratisation

Notwithstanding, gaseous chemical weapons such as chlorine, phosgene, mustard gas and nerve agents such as sarin faced two major problems. One is that are that they are not really very useful as weapons, especially against a peer or near peer enemy. Again absence of usage provides the best indicator:

The Pentagon considers these weapons too unreliable for use in battle–the wind could blow the chemicals back on your own troops. And with the exception of napalm and Agent Orange used in Vietnam, the United States is not known to have used chemical weapons in battle since World War I.

If they were really useful as weapons then we might expect them to be used – the US is after all in a constant state of war – and in that case we would be told, in accordance with Churchill, what humane weapons they are. And if a chemical weapon does have some value in battle – white phosphorous seems to have been quite frequently used by the United States in the Middle East – then it is not a chemical weapon. Or to be more precise, when pre-invasion Iraq used white phosphorous it was a chemical weapon, when the US does it becomes a conventional weapon.

Chemical weapons have been transferred from the War Department to the intelligence agencies to be used as covert weapons or as part of false flag operations.

However chemical weapons do have their uses for major powers, but not in the Churchillian mode. Chemical weapons have been transferred from the War Department to the intelligence agencies to be used as covert weapons or as part of false flag operations. However even here they appear to be fallible, or at least susceptible to operator error, if we are to believe the British allegation that nerve agents were used against the Skripals in Somerset in March. Despite the ‘novichoks’ family of nerve agents being described as especially virulent the Skripals themselves, and an infected police office have all survived, a doctor who attended them was only temporarily affected, and no one else seems to have been affected. There are more certain ways of killing people; the ‘Mossad method’– two men, a gun and a motorbike, comes highly recommended. Or, to add another twist, if you want to kill someone you do it as unobtrusively as possible – the best murder is the one that is not recognised as such. If, however, you want the assignation to be very visible and to attract attention in order to smear an adversary or for some other covert purpose, then you use some exotic, and preferably monstrous method, and nerve agents fit that bill nicely. The Skripal, Litvinenko, and the Kim Jong Nam incidents probably share this characteristic.

Minor powers, such as Syria and North Korea, might see chemical weapons as a useful deterrent against more powerful predators and one cheaper and more accessible than nuclear weapons. This would be not so much for confidence in their effectiveness as weapons but because of their psychological impact. For deterrence, perception of danger is more important than efficacy. The difference between major and minor powers is reflected in the distinction between the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); the first prohibits the weapons under discussion to all signatories and the second, while prohibiting to most countries merely promises that the Nuclear Weapons States, then in 1968 only major powers, will move towards that goal. That movement has been sluggish and many would argue, non-existent.

The second is that the diffusion of technology means that they are no longer the monopoly of great powers but are now within the reach of the modern version of Churchill’s ‘uncivilized tribes’, such as Iraq and Syria, and worse still non-state actors such as the Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo which used sarin in the Tokyo subway in 1995.They also produced other nerve agents such as VX

The Chemical Weapons Convention and demonization

The Chemical Weapons Convention and demonization

This combination of factors led to the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1997. Chemical weapons were not particularly useful for the major powers (not least the US) and they could be dangerous to the users. Further, they were increasingly available to minor states and non-state actors, they had a bad reputation and they had no great attraction for the military-industrial complex which prefers more expensive ways of killing people. The stage was set for the prohibition of chemical weapons (or at least some of them) and their demonisation. Prohibition and demonisation were paired. It would not have been good PR to give all the reasons for probation, such as ‘we not find them particularly effective’ so it was wise to focus on their undeniable malevolence and claim that was what it was all about. Wrapping self interest in the shroud of virtue.

There is no strong argument that chemical weapons are particularly worse than others, either in the horrible deaths and deaths they can inflict or killing indiscriminately – it would be difficult to compete with the bombing of Dresden, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki , the fire bombings of Tokyo, or carpet bombing in general, for which the United States has been exceptionally adept, for indiscriminate and horrendous killing.

Strategic skullduggery

The demonisation of chemical weapons has provided two implements for strategic skulduggery.

Firstly there is the argument (when convenient) that ethics overrides legality and moral revulsion renders any pettifogging adherence to international law irrelevant. Thus an article in The Atlantic explained why bombing of Syria to replace its recalcitrant government with a more compliant, albeit Islamist one, in violation of the law is an ethical necessity:

The “chemical and biological warfare is different” strand of argument is critical, because if the United States acts it will be doing so, at least ostensibly, for moral reasons. There are strong arguments that there is no authority in international law for U.S. deployment of military force in these circumstances. That is why the reasons behind the protocol cast a long shadow over today’s debate—a debate that is now about the ethical necessity, not the questionable legality, of U.S. military strikes to punish the Syrian regime for gassing its civilians.

The ‘ethical necessity’ is reinforced by the assertion that the Syrian government is especially wicked because it is ‘killing its own people’. Abraham Lincoln, who had some familiarity with civil war, being involved in the bloodiest in history, would have been bemused by that argument. Ironically, it was during that civil war that Americans first proposed using chemical weapons

Secondly, the possession of chemical weapons is by its nature not susceptible to easy empirical verification. It thus provides fertile ground for accusations without any need of producing evidence. For instance we are told that:

US and South Korean experts believethat, in fact, North Korea does have a significant chemical weapons programme, with stockpiles of munitions containing nerve, choking and blister agents; such substances as phosgene; hydrogen cyanide; mustard; and sarin.

No evidence is produced and none can be demanded. Aircraft carriers and tanks are visible and can be counted. The initial stages of nuclear weapon development have traditionally required physical tests which can be scientifically identified – the US should know since it has conducted over a thousand. (Israel has not conducted any direct tests of its nuclear arsenal, but then it has obliging friends). Chemical weapons are different. To the untrained eye a chemical weapons establishment can look like a milk powder factory or a pharmaceutical plant, and when the US bombers have left and the journalists arrive it is discovered that that in fact is what they are.

That is not to say that some degree of verification is absolutely impossible. One of the functions of the OPCW is to do just that. The US has accused both Russia and Syria of violating the CWC by possessing (and using) chemical weapons. However while the OPCW has verified the compliance of both Russia and Syria the US has still not complied with its obligations under the treaty. Clearly no verification can be absolute; it is impossible to prove a negative

Chemical weapons provide an evidence-light, accusation-heavy environment where hypocrisy and disinformation jostle for attention rendering them attractive to operators like John Bolton. For instance, one of his ploys (amongst a number of others) to derail any deal between the US and North Korea is his attempt to bring chemical weapons into the agenda. If that were to be made a condition of an agreement then none can be made since the non-existence of a chemical weapons arsenal can never be proven.

Syria and false flag operations

This characteristic of chemical weapons where possession and culpability is inherently difficult to ascertain gives rise to allegations of the use of chemical weapons which in recent years has focused on Syria. Since the incidents occur in contested areas impartial professional investigation can be very difficult though there are suspicions that OPCW has been under pressure not to undertake its duties too vigorously. For Instance it never made a visit to Khan Sheikhoun (despite the urging of Russia and Syria) on the grounds that the area was under the control of ‘rebels’ (Al Nusra by repute) and so the security of its team could not be guaranteed. Nevertheless it accepted samples as evidence in Turkey from these same rebels despite their being no chain-of-custody to guarantee their validity.

This combination of attributes have made chemical weapons a prime candidate for false flag incidents. Their possession is problematic, difficult to verify and impossible to disprove. The manufacture is relatively easy and accessible – if Aum Shinrikyo can produce sarin why not Al Nusra? The delivery can be cheap and rudimentary – no stealth bombers required. All this means that attribution of blame is very murky and contested. Finally, and crucially their hyped reputation as being a weapon that only monsters would use tends to drive out rational and critical assessment. The more horrible something is perceived to be the more likely we are to believe it, which is why war propaganda tends to be particularly gruesome.

False flag incidents can be very effective in precipitating desired outcomes – the Marco Polo Bridge incident which provided the excuse for the Japanese invasion of China proper in 1937, the Gleiwitz incident, preceding the German invasion of Poland in 1939 and the Gulf of Tonkin incident which was used to escalate the war against Vietnam are variants on the theme. However false flag operations can lead to what might be called the Red line Trap.

The Red Line Trap

Setting a ‘red line’ is usually considered by strategists to be unwise. If you say to the other side “if you cross the Rubicon we will go to war” then you are handing the decision on when, and indeed whether, to the adversary. American presidents have tended to steer clear of the phrase in such circumstances. However Barack Obama went further into losing control of the situation when he stumbled into declaring the use of chemical weapons in Syria to be a ‘red line’ in an off-the-cuff remark. It appears that he was manipulated into this by unnamed intelligence officials:

The origins of this dilemma can be traced in large part to a weekend last August, when alarming intelligence reports suggested the besieged Syrian government might be preparing to use chemical weapons. After months of keeping a distance from the conflict, Mr. Obama felt he had to become more directly engaged.

In a frenetic series of meetings, the White House devised a 48-hour plan to deter President Bashar al-Assad of Syria by using intermediaries like Russia and Iran to send a message that one official summarized as, “Are you crazy?”

Of course he should have been suspicious. Why would President Bashar al-Assad be so crazy as to use a weapon with such limited efficacy and calamitous political consequences? He should have realised that the Syrian government was highly unlikely to employ chemical warfare but the jihadists did have good reason. And so it appears it came to pass.

Evidentiary difficulties

Evidentiary difficulties

Any assessment of the use of chemical weapons is fraught with difficulties. Chemical weapons, by their nature and often by mode of use are inherently challenging to investigate and this is compounded when incidents happen, as they usually do, in contested areas. Evidence from the governments involved and from partisan and propaganda outfits such as the England-based, ostensibly one-man band Syrian Observatory for Human Rights or the Western-financed White Helmets carry little evidentiary weight. Unfortunately this skepticism extends to the Security Council and to UN agencies such as Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (IICoISyria) and the Organization for the Prevention of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).The IICoISyria, co-chaired by US diplomat Karen Koning Abuzayd, is barred from investigations in Syria itself because, according to one Swedish academic study, both the government and the peopleregard it as biased. Instead it remains in Geneva and culls its information from anti-government sources. The OPCW, does not attribute culpability only evidence of use, and has in any case been loath to carry out on-site inspections.

The United States does not have complete mastery over the UN, to the frustration of successive ambassadors to the UN such as John Bolton, Samantha Power and Nikki Haley. There was, for instance, an apoplectic reaction in May 2008 to Syria assumingthe rotating presidency of the United Nations-backed Conference on Disarmament. Disarmament is a subject very dear to heart the United States; that of other countries, naturally, not of its own. Nevertheless in general the United States has a dominating influence over the UN, its agencies, and the careers of their staff, and so investigations on contentious subjects, where the wrong results might incur the wrath of the US, should be treated with great caution. The power of the Unites States was exemplified by the dismissal of the then Director-General of the OPCW, Jose Bustani, in 2002 in a coup personally engineered by John Bolton, who is reported to have threatened ‘We Know Where Your Kids Live’. The current Director-General, Ahmet Üzümcü, does not seem to have incurred the ire of Mr Bolton, suggesting that lessonshave been learned. Recent French moves to extend OPCW’s mandate to attribution probably indicates Western confidence that OPCW is a tamed animal. That this initiative came from France is no accident. It appears that French intelligence has deep contacts in Syria, presumably a legacy of the colonial past, so much so that they were able to carry out an investigation in Al Nusra-controlled Khan Sheikhoun where OPCW feared to tread.

Reported casualties from chemical weapons seem too small to be the result of concerted government action. There is a suspicious imbalance between the number of alleged incidents and casualties. For instance Human Rights Watch, from its niche within the US foreign policy architecture claims that ‘the Syrian government is responsible for the majority of 85 confirmed chemical weapon attacks’ between August 2013 and February 2018. Strangely the article gives no figures for casualties but a recent one in the New York Times while producing no cumulative number speaks of ‘dozens’ in Douma, 1400 in Ghouta and ‘more than 80’ in Khan Sheikhoun. In other words, very small numbers in the context of a war to which that article attributes 120,000 civilian deaths while others suggest a total of 500,000. If the Syrian government is going to risk international condemnation, and American attack, by using chemical weapons we might expect it to deploy them to more military effect. Former weapons inspector Scott Ritter, writing on the Khan Sheikhoun incident notes that ‘Chemical ordnance is not intended for precise strikes against point targets, but rather delivery of the agent to an area. For this reason, they are not dropped singly, but rather in large numbers.’ And if chemical bombs are dropped in large numbers on a populated area we might expect more than 80 casualties.

The evidence about the use of chemical weapons in Syria tends to be circumstantial with little onsite inspection by outside agencies. It is usually based on uncorroborated allegations from anti-government forces with no ‘chain of custody’ for samples. There is, however, one piece of evidence which, it is claimed, emanates from the Syrian government. In 2013 It was reported in Bild am Sonntag that:

Syrian brigade and division commanders had been asking the Presidential Palace to allow them to use chemical weapons for the last four-and-a-half months, according to radio messages intercepted by German spies, but permission had always been denied, the paper said.

It would seem very unlikely that a field commander would use chemical weapons after an explicit prohibition from the president. That was before Syria joined the CWC and formally relinquished chemical weapons, as verified by the OPCW. After that the constraints against using chemical weapons would be overwhelming, both in terms of availability (the OPCW verified they had been disposed of) and presidential injunction.

Balance of probabilities suggests false flag operations

So, while there can never be certainty in these matters, it seems clear that on the balance of probabilities the alleged chemical weapons incidents in Syria have been basically a series of false flag events orchestrated by anti-government jihadists, with perhaps some help on occasions from interested outside forces.

Which brings us back to Obama’s red line. After having fallen into the trap he had the sense to draw back, refusing to go down the path of increased direct military intervention. He lost face over this – John McCain who had visited rebels, some allegedly with ISIS connections, in Syria – quipped that the red line had been ‘apparently written in disappearing ink’. Obama, in retirement, said that backing out of his red line dilemma (he didn’t put it quite that way of course) was the most politically courageous decision he had taken as president.

The New York Times article of 4 May 2013, makes interesting reading because it presumably reflects the concerns of high officials that the US was now very vulnerable to manipulation by the jihadists:

With such an evocative phrase, the president had defined his policy in a way some advisers wish they could take back…

Further complicating the president’s choices is the murky nature of the evidence against Syria, a constant concern because of the lingering memories of mistaken intelligence on Iraq’s weapons a decade ago. American intelligence agencies have medium to high confidence that chemical weapons have been used in Syria, but it is not completely clear who was using them.

The Obama administration recognizes that the rebels and their supporters have an incentive to assume or even exaggerate the use of such weapons because it may be the one thing that could draw in direct Western military intervention against Mr. Assad. The rebels have access to information online about the effects of the weapons, so they may know what symptoms to describe to make their claims seem real.

Whilst the alleged incidents were small scale the Administration could resist the calls to action but then came the Ghouta incident of 21 August 2013, with claims of up to 1,800 fatalities. If this isn’t a red line, what is? demanded The Economist.

The media played its familiar role of obfuscation and disinformation. For instance on 4 September 2013 MSNBC ran a story headed ‘Obama: ‘I didn’t set a red line, the world set a red line’. The article had no doubts about the August events in Ghouta (which had precipitated the ‘red line’) and claimed that ‘the Syrian president, who hasn’t denied that chemical weapons were used in prior months, threatened “negative repercussions” if the United States launches an attack against his country.’ This is clearly meant to be read as an admission of guilt. However, the linked article, published by MSNBC just two days earlier begins: ‘Syria President Bashar al-Assad has denied ordering an Aug. 21 chemical attack that the U.S. government said killed nearly 1,500 people in a Damascus suburb.’

The White House issued a statement on 30 August declaring that:

The United States Government assesses with high confidence that the Syrian government carried out a chemical weapons attack in the Damascus suburbs on August 21, 2013.

We were spared the trouble of making our own assessment with the familiar excuse:

To protect sources and methods, we cannot publicly release all available intelligence…

Nevertheless independent analysts managed to scrutinise the available evidence and came up with different conclusions, demolishing the US government’s assessment. Prominent among them were famed investigative reporter Seymour Hersh (whose reputation stretched back to his revelations about the My Lai massacre) and former UN Weapons Inspector Richard Lloyd and Professor Theodore Postol of MIT. Subsequently in February 2018 US Defense Secretary Mattis admitted:

The U.S. has no evidence to confirm reports from aid groups and others that the Syrian government has used the deadly chemical sarin on its citizens, Defense Secretary Jim Mattis said Friday. “We have other reports from the battlefield from people who claim it’s been used,” Mattis told reporters at the Pentagon. “We do not have evidence of it.”

Whatever the actual facts of the case the US government had accused the Syrian government of the attack so, from the American perspective, Obama’s red line had been crossed and he was in a quandary. Apart from the problems of military action his difficulties were compounded, according to Hersh, by revelations from the British chemical weapons establishment at Porton Down, that the type of sarin used in the incident didn’t match that known to exist in the Syrian army arsenal. Obama sidestepped the dilemma by saying the action was postponed while he sought Congressional approval. He was then rescued by presidents Putin and Assad with the news that Syria would accede to the Chemical Weapons Convention and hence divest itself of chemical weapons. Who initiated this is unknown but in the circumstances it would have been an easy, though painful decision for the Syrian government to make. Chemical weapons had served as a deterrent against the much more powerful, and nuclear-armed, Israel. The United States was the overwhelming present danger and Syria could not use chemical weapons against the US; it did not have the long-range delivery systems.

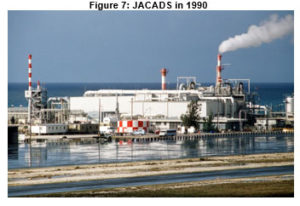

Syria joined the CWC on 14 September 2013 with an intended date for destruction or removal of 30 June 2014 and this ‘indefinitely stalled the prospect of American airstrikes’. The process was delayed by the war but on 4 January 2016 the OPCW declared ‘Destruction of declared Syrian chemical weapons completed’.

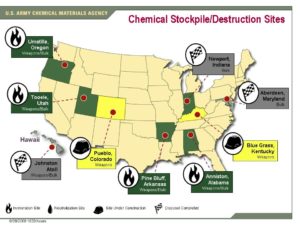

Accession to CWC rescues Obama but doesn’t end incidents

However that, of course, was not the end of it. The jihadists still had reasons to lure the US into direct intervention, and those reasons had become even more compelling when, after Russian intervention, they were being relentlessly driven out of territory they had conquered. Part of the problem was that by the nature of things, there could never be proof that the Syrian government had not sequestered away some chemical weapons. This was alleged by the US even though the Obama administration had boasted that it had ‘got Syria to ‘verifiably give up its chemical weapons stockpile’. And of course the same doubts would remain when the US finally follows Syria’s path and officially finalises the destruction its chemical weapons (not before 2023 at the earliest according to one report).

With its accession to the CWC the disincentive to the Syria Government to use chemical weapons greatly increased, and with success against the rebels the incentive similarly decreased. To use chemical weapons and risk the political consequences when your back was against the wall was one thing, to use them when you are winning is another. The allegations of course continued and while then Secretary of State John Kerry made the usual condemnations the Obama administration resisted pressure, for instance from Samantha Power, to bomb and ‘to punish’ the Syrians. Fear of getting entangled with the Russians, who had by then intervened military in Syria, the restraining influence of Sergei Lavrov, with whom Kerry reportedly had good relations, and the rise of ISIS were all factors.

The Trump administration introduces a different calculation

For the Trump administration, the situations and motivations are quite different. It is not merely that Trump is less intelligent than Obama. More important is that he has even less of a coherent strategy on Syria, or elsewhere for that matter. US foreign policy is more driven by domestic factors than that of any other country but grand strategy a la Keenan, Kissinger or Brzezinski has generally played a counterbalancing role and at times a dominant one. With no coherent geopolitical strategy then the domestic becomes all-important and long-term foreign consequences fade into the background. The Trump administration doesn’t do grand strategy. Even when there is a focus on foreign policy, as with Bolton, there is still no strategy. Bolton is consumed by the desire to destroy Iran and North Korea but it appears that he does not have a coherent idea of how that destruction would fortify American hegemony; the act is sufficient in itself and damn the consequences even if that might mean war with China. Moreover, the US president has much more freedom of action in foreign affairs than in domestic politics, so when things get difficult at home there is a tendency to throw weight around abroad.

Trump has a further strong motive to pick up any bait the jihadists might throw him. He sees it as a way of demonstrating that he is no ‘Putin Puppet’.

Khan Sheikhoun and Douma: fraudulent incidents, fraudulent responses

There have been two major alleged chemical warfare incidents in Syria in Trump’s term of office so far. The first was at Khan Sheikhoun on 4 April 2017 and the second at Douma on 7 April 2018. In both cases the US, and its allies, accused the Syria government of using chemical weapons and in both incidents it is virtually certain that the jihadists utilized them as false-flag operations in an attempt to bring in the Americans to rescue them as their fortunes flagged. In the case of Douma there were serious doubts that any chemical weapons had actually been used. As Scott Ritter aptly put it in respect of Khan Sheikhoun it was a case of ‘Wag The Dog — How Al Qaeda Played Donald Trump And The American Media’. And if the tail was wagging the dog it was not because the tail – evidence of the Syrian government’s culpability –was strong but because the tail – here Donald Trump – was happy to be wagged. He was setting a foolish precedent.

It might have been strategically unwise but his airstrikes against Syria – on 6 April 2017 and 14 April 2018 – did bring him certain short term benefit. A majority of the public supported them, virtually all the mainstream media were exuberant and the pundits were euphoric: Fareed Zakaria proclaimed on CNN after the second attack that by displaying such courage and determination , ‘I think Donald Trump became president of the United States’. Lobbing missiles and dropping bombs on foreigners who cannot retaliate tends to be popular.

However, whilst the avowed reasons for the airstrikes were fraudulent so appropriately were the strikes themselves. Defense Secretary Mattis made sure that the Russians and Syrians were warned in good time and little damage was done. It was all symbolism for domestic consumption and to stoke Trump’s ego.

The danger of precedent

The danger of precedent

The American airstrikes did little to save the jihadists but the precedent established in 2017 was reinforced in 2018. The way to get the Americans to take action was to construct a chemical weapons incident. And if the American attacks were not vigorous enough that merely gave further impetus for more incidents.

Admiral Lord West, former First Sea Lord and Chief of the [British] Naval Staff candidly admitted in a BBC interview after the Douma incident that had he been advising the Islamists facing defeat he would have suggested fabricating a chlorine attack, as he thought they had, to provoke American intervention. As a naval man he would be familiar with the use of deception and subterfuge in war; after all, the very phrase ‘false flag’ has nautical origins.

The lesson, he suggested, was that the US was being manipulated –‘let’s face it, if [Assad] hasn’t done it then that is extremely bad news’.

This note of realpolitik caution is not widely shared among the Western political and military elite, nor the media that articulate and disseminate their opinions. And therein lies the danger, which extends beyond the immediate, and beyond Syria.

Catalyst for catastrophe

Chemical weapon incidents are relatively easy to fabricate even by relatively small groups of non-state actors, especially if they have access (as they do in Syria) to resources from interested states. Three decades of Islamist guerrilla warfare has generated and spread all sorts of military techniques from bombs through to chemical weapons. The Islamist jihad is by its nature multinational and fighters from Chechnya and Xinjiang have been prominent in Syria. What is learnt in Syria can be taken home, or elsewhere. And there is no reason for these techniques not to extend beyond Islamists.

This ease of fabrication and the inherent difficulties of attribution coupled with the ritual demonisation of chemical weapons as the ultimate crime which only a monster would use presents a standing invitation. If a group wants to invoke Western action, military or economic, against a government it is fighting then a chemical weapons false flag operation is an attractive option. It would, of course, only be of use if the West was hostile to the government in question; it would work in Xinjiang but not in Kashmir. However that still leaves plenty of scope.

Chemical weapons, of course, are horrible in themselves but the real danger, and one that could lead to far more deadly consequences than any of the chemical incidents in Syria, indeed greater than the sum of chemical warfare casualties since their first major use in the First World War, is their possible role as a false flag catalyst instigating and provoking wars that might employ more effective weapons.

CovertAction Magazine is made possible by subscriptions, orders and donations from readers like you.

Blow the Whistle on U.S. Imperialism

Click the whistle and donate

When you donate to CovertAction Magazine, you are supporting investigative journalism. Your contributions go directly to supporting the development, production, editing, and dissemination of the Magazine.

CovertAction Magazine does not receive corporate or government sponsorship. Yet, we hold a steadfast commitment to providing compensation for writers, editorial and technical support. Your support helps facilitate this compensation as well as increase the caliber of this work.

Please make a donation by clicking on the donate logo above and enter the amount and your credit or debit card information.

CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and your gift is tax-deductible for federal income purposes. CAI’s tax-exempt ID number is 87-2461683.

We sincerely thank you for your support.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the sole responsibility of the author(s). CovertAction Institute, Inc. (CAI), including its Board of Directors (BD), Editorial Board (EB), Advisory Board (AB), staff, volunteers and its projects (including CovertAction Magazine) are not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement in this article. This article also does not necessarily represent the views the BD, the EB, the AB, staff, volunteers, or any members of its projects.

Differing viewpoints: CAM publishes articles with differing viewpoints in an effort to nurture vibrant debate and thoughtful critical analysis. Feel free to comment on the articles in the comment section and/or send your letters to the Editors, which we will publish in the Letters column.

Copyrighted Material: This web site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. As a not-for-profit charitable organization incorporated in the State of New York, we are making such material available in an effort to advance the understanding of humanity’s problems and hopefully to help find solutions for those problems. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. You can read more about ‘fair use’ and US Copyright Law at the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Republishing: CovertAction Magazine (CAM) grants permission to cross-post CAM articles on not-for-profit community internet sites as long as the source is acknowledged together with a hyperlink to the original CovertAction Magazine article. Also, kindly let us know at info@CovertActionMagazine.com. For publication of CAM articles in print or other forms including commercial internet sites, contact: info@CovertActionMagazine.com.

By using this site, you agree to these terms above.

About the Author

Tim Beal is a retired academic who taught on Asia and international marketing for many years at Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand.

Beal has researched and written on many aspects of Asia, ranging from Korea to India. He is currently working on an extended essay on “Imperialism and Korea” for the forthcoming second edition of The Palgrave Encyclopaedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism edited by Immanuel Ness and Zak Cope.

He also maintains a website focused on Asian geopolitics.